The COVID-19 pandemic changed almost everything about the 2020 American elections. The Biden campaign made much of the federal failure to combat the disease. President Trump politicised the response, appearing to run against practices like mask-wearing that are designed to slow infections (Milosh et al. 2020). Campaign techniques changed dramatically, particularly on the Democratic side, with door-knocking and in-person rallies falling off and outreach moving to video and virtual realms.

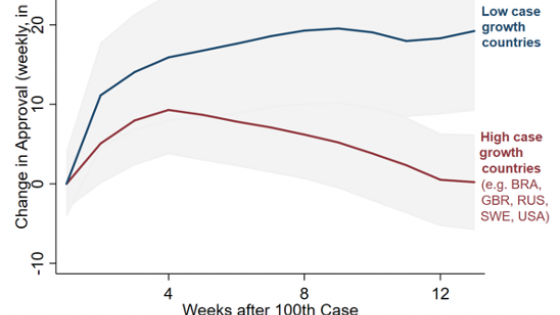

Polls showed that most Americans disapproved of President Trump’s response to COVID-19 – a 17-point chasm by election day. A cross-country analysis of polling data showed that governments that failed to contain COVID-19 infections suffered falling approval rates (Herrera et al. 2020).

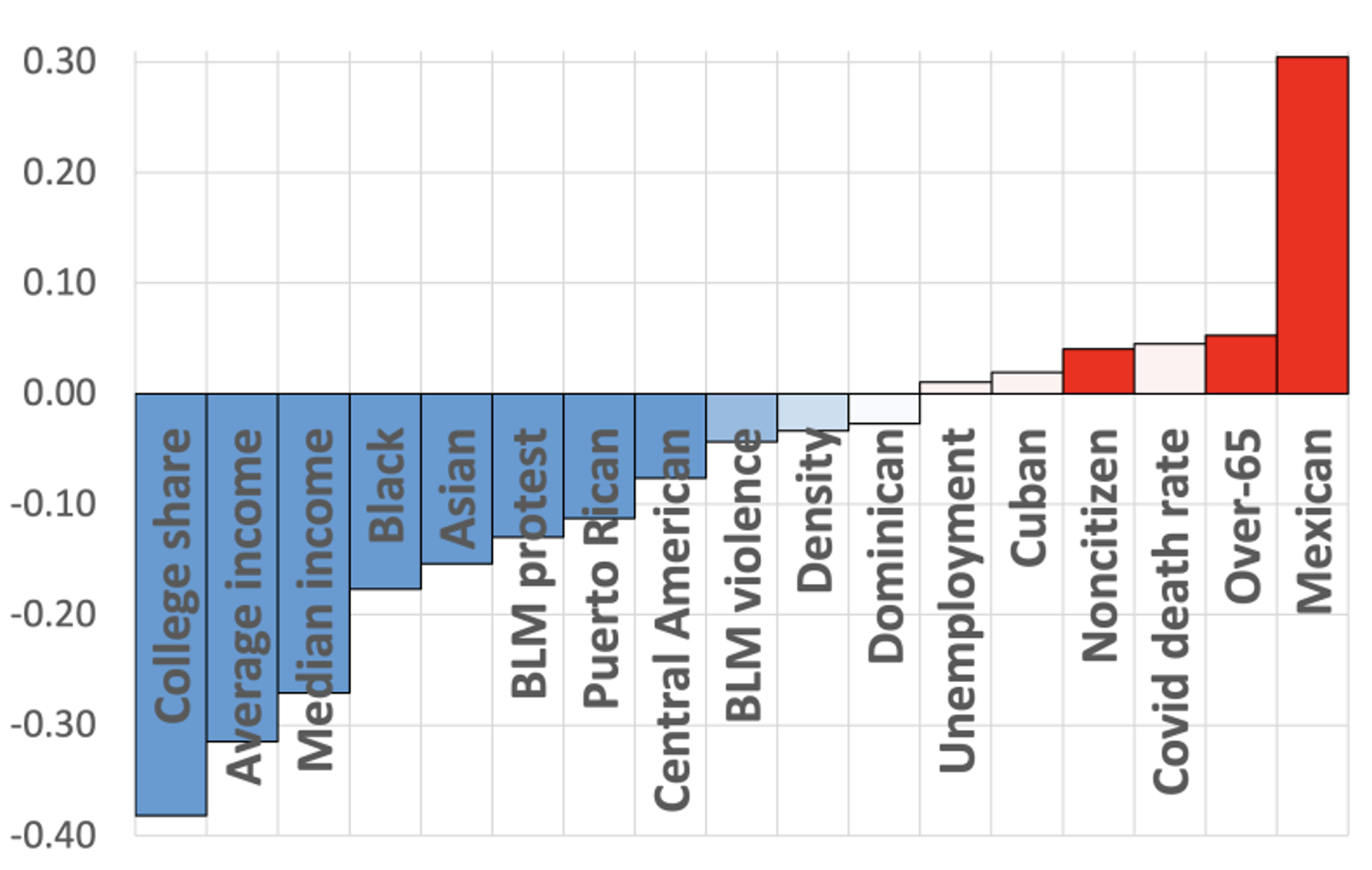

And yet, the pandemic appeared to have remarkably little effect on the American electoral returns (Wilson 2020, McMinn and Stein 2020). In fact, when we ran a simple set of correlations using county-based data (Abad and Maurer 2021), we found that COVID-19 death rates were weakly correlated with a swing towards Donald Trump between 2016 and 2020 (Figure 1).

Figure 1 Associations between county-level characteristics and the swing towards the GOP in the 2016 and 2020 presidential elections

Notes: Blue bars indicate a swing towards the Democratic Party; red towards the Republican Party.

Can this be right? Did the pandemic really not matter to the ‘pandemic election’ of 2020? A good way to start analysing this question is to ask what effect we should expect a pandemic disease to have on election results. The best parallel history provides is the 1918-19 influenza pandemic, which broke out during an election year and killed over 600,000 Americans (Abad and Maurer 2021).

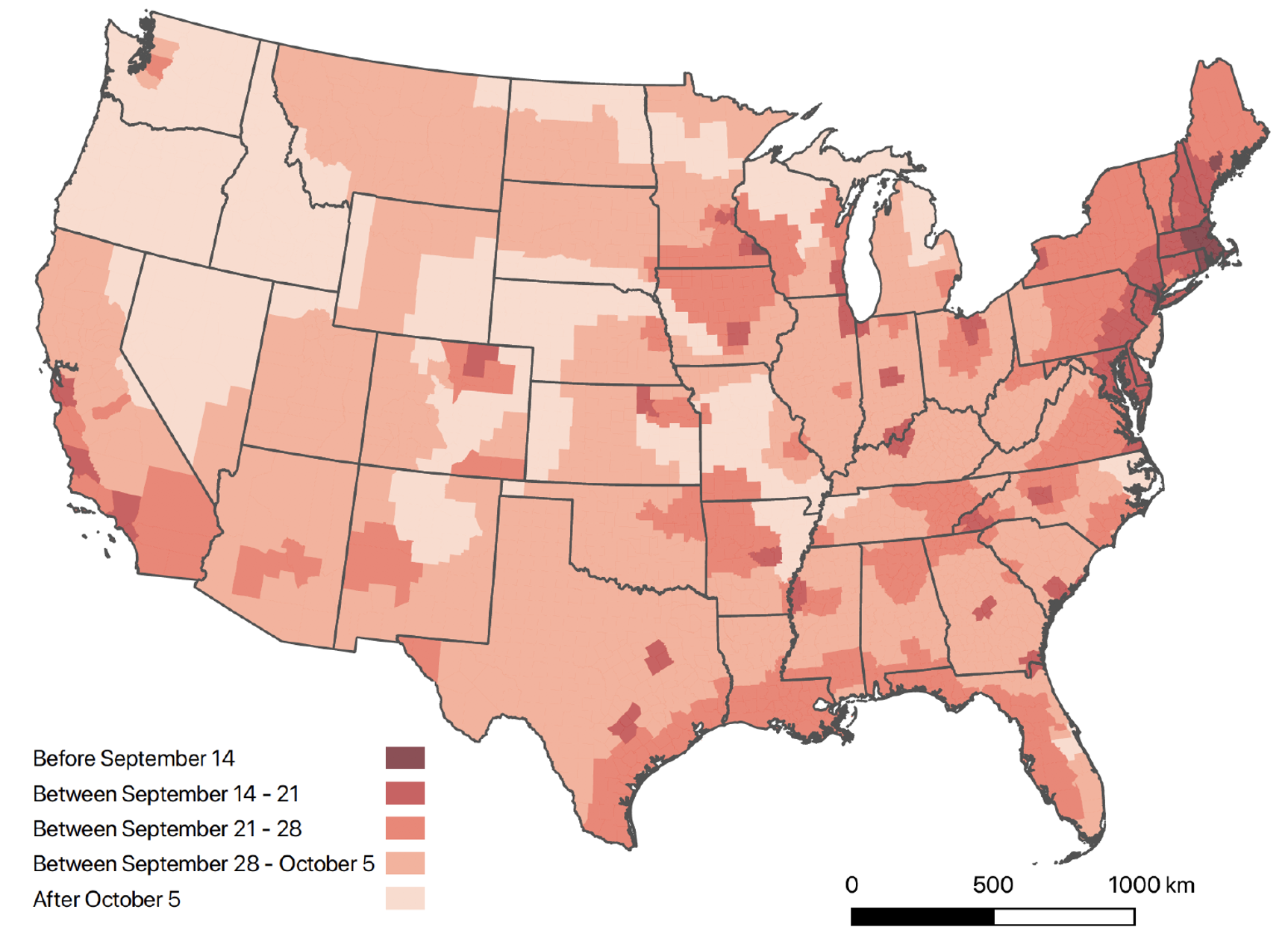

In September 1918, the second wave of the flu arrived in the US at Fort Devens, Massachusetts, and rapidly spread across the country (Figure 2). Excess mortality exceeded 600,000. Children lost their parents; grandparents outlived their adult children.

Figure 2 The spread of the second wave of the Spanish flu, 1918

We assembled a county-level dataset of votes by party for three levels of government: the 1918 congressional elections, the 1918, 1919, and 1920 gubernatorial elections, and the 1920 presidential election. We combined these data with new estimates (derived from census data) of county-level excess mortality. We obtained county-level economic and demographic controls from the census.

We found no discernible effect on turnout. The arrival of women’s suffrage was not the reason for low turnout. New York was the only state in our sample to allow women’s suffrage for the first time in the 1918 election; state-level fixed effects absorbed other states that switched in 1919 as a result of the ratification of the 19th Amendment guaranteeing American women the right to vote.

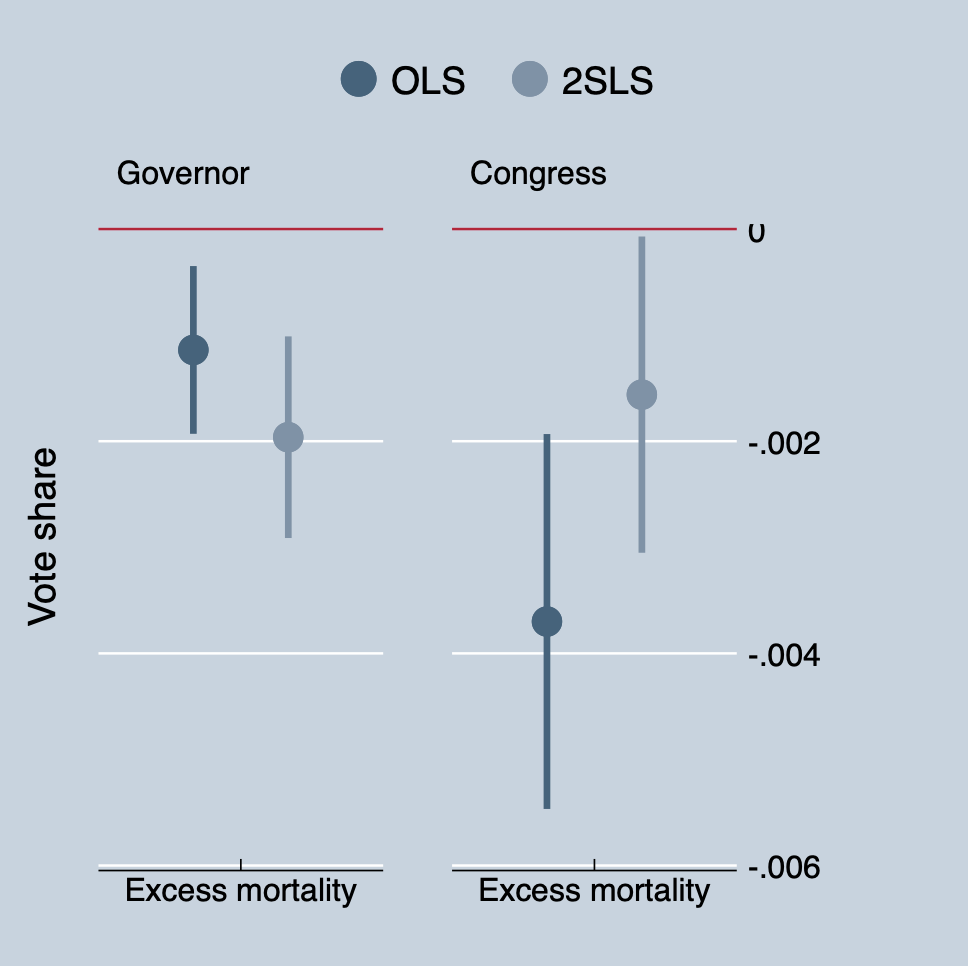

But we did find that the more the Spanish flu hit a county, the more the voters swung away from the incumbent governor and congressional Democrats. These findings are in line with Heersink et al. (2017), who found that counties hit hard by the Great Mississippi Flood of 1927 punished Herbert Hoover in 1928. The relationship held up when we used the underlying disease environment and a county’s distance to military camps (which spread disease) as instruments (Figure 3).

Figure 3 Effect of Spanish flu excess mortality on vote shares

In short, our regression results indicate that voters did indeed blame incumbent parties for bad outcomes. But it is one thing to find an econometric result; it is another to show that the result makes sense, given what we know about the history.

There are a lot of misconceptions about the context of the Spanish flu. The first is that voters were unaware of the flu outside their immediate locality because of wartime censorship. The second is that the government didn’t react to the pandemic. The third is that voters had no reason to believe that the government could, would, or should protect them against infectious disease outbreaks, which meant that the pandemic never became a political issue.

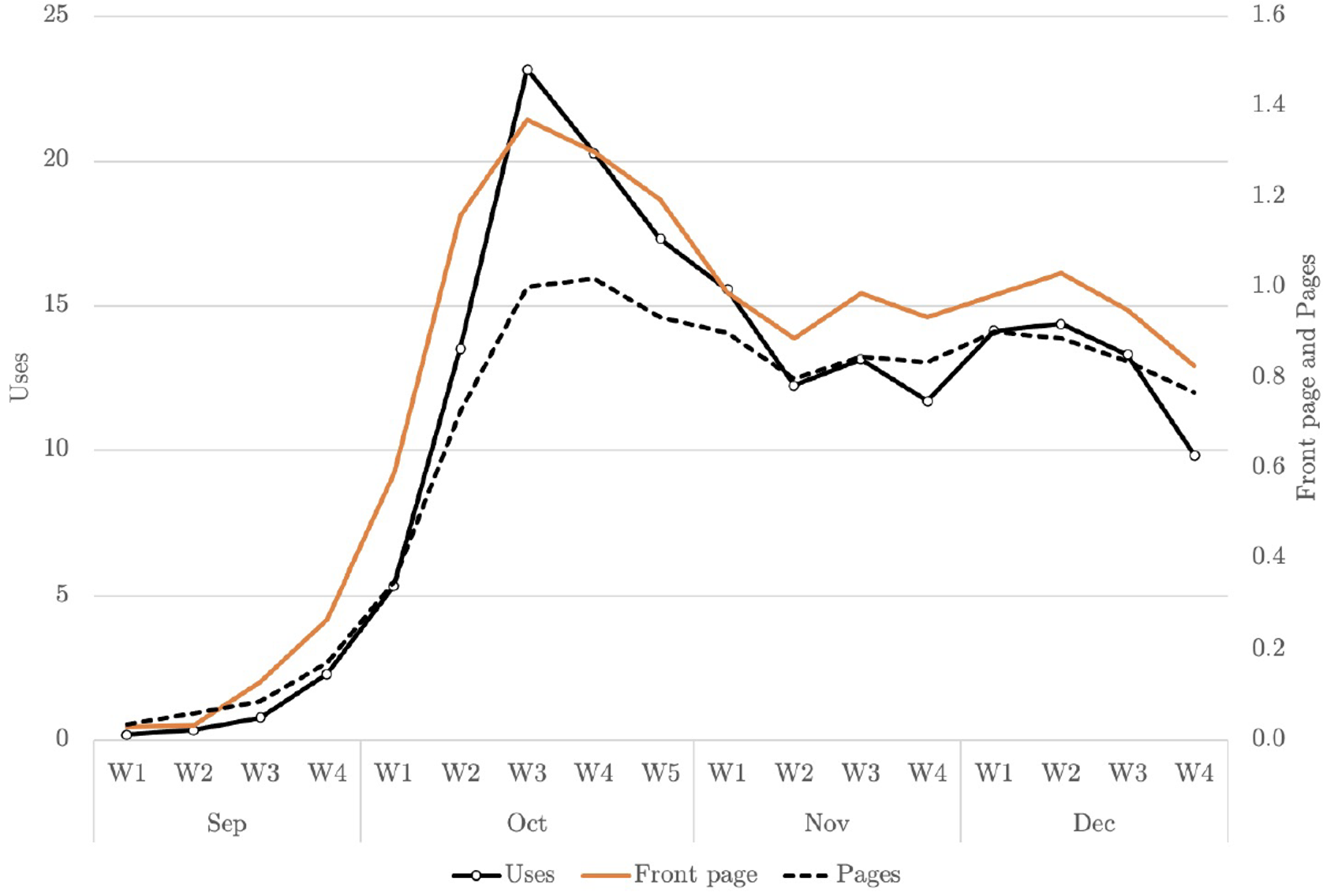

The view that wartime censorship kept the pandemic out of the papers appears to come from an interview with historian John Barry in which he asserted that 1918 newspapers provided “lots of war coverage but very little about the pandemic.” This struck us as odd, given that Barry (2004) contains no evidence of such censorship. We analysed 495 daily newspapers from the beginning of September 1918 to the end of 1918 and found that flu coverage exceeded war coverage during the peak of the pandemic (Figure 4).

Figure 4 Flu to war mentions in the newspapers

In addition, the federal government printed tens of millions of pamphlets and posters to alert the public and encourage behaviour that would slow the spread of the flu. In Alfred Crosby’s words, “If influenza could have been smothered by paper, many lives would have been saved in 1918.”

Figure 5 US Public Health Service pamphlet

Did the federal government fail to react to the crisis? It is true that President Wilson remained oddly silent. But once Philadelphia and Chicago succumbed, Congress appropriated $1 million (the 2019 equivalent of $253 million as a share of GDP) to mobilise civilian doctors into the US Public Health Service (USPHS) and placed the Army and Navy’s health departments – bloated to a huge size by the war mobilisation – at the USPHS’s disposal.

Public laboratories in New York and the Mayo Clinic in Minnesota worked overtime to develop a vaccine. They achieved one in record time, but the problem was that they did not understand the aetiology of influenza and they vaccinated against the wrong pathogen. Pfeiffer’s bacillus was a secondary invader of flu victims but did not cause the disease. Scientists realised that they had the wrong cause by July 1919 but that was too late to stop New York and Illinois from spending millions on useless vaccines.

The pandemic, meanwhile, dominated state politics. State and local governments banned public gatherings, shut down bars and restaurants, closed schools, staggered hours, and mandated mask-wearing. In California, the state had to crack down on San Diego when the city council tried to revoke closure orders and mask mandates. San Franciscans organised an “Anti-Mask League” and the jails filled up with people who refused to wear them. (Several people were shot in altercations over masks and someone sent a mail bomb to the head of the Board of Health.)

In New York, the governor mysteriously discovered outbreaks in towns where his Democratic opponent planned to speak. An angry Al Smith proclaimed that GOP officials “want to prevent the spread of Democratic doctrine rather the spread of Spanish influenza.” Governor Whitman’s ploy did not work and when the New York GOP lost they blamed their defeat on the flu.

In short, we found a significant effect of flu deaths on election outcomes which we failed to erase despite myriad attempts. The effect we found, however, was relatively small. Roughly speaking, an increase of one standard deviation in flu deaths implied a shift of 2.8 percentage points against the congressional Democrats and a 0.8-point shift against the governor’s party.

Most congressional elections, however, shifted by significantly more than that. Only in Maryland were deaths high enough to have swung the gubernatorial election. In a sense, we have the best sort of null result – a very precisely estimated small effect! Voters cared about the Spanish flu and they held politicians accountable. They just cared about other things much more.

References

Abad, Leticia, and Noel Maurer (2021), “Do pandemics shape elections? Retrospective voting in the 1918 Spanish Flu Pandemic in the United States”, CEPR Discussion Paper 15678.

Heersink, Boris, Brenton Peterson and Jeffrey Jenkins (2017), “Disasters and elections: Estimating the net effect of damage and relief in historical perspective”, Political Analysis 25(2): 260–68.

Herrera, Helios, Maximilian Konradt, Guillermo Ordoñez and Christoph Trebesch (2020), “Corona politics: The cost of mismanaging pandemics”, Covid Economics 50: 3–32.

McMinn, Sean, and Rob Stein (2020), “Many places hard hit by COVID-19 leaned more toward Trump in 2020 than 2016”, NPR, 6 November.

Milosh, Maria, Marcus Painter, Konstantin Sonin, David Van Dijcke and Austin L Wright (2020), “Unmasking partisanship: How polarization influences public responses to collective risk”, University of Chicago, Becker Friedman Institute for Economics Working Paper (2020-102).

Wilson, Chris (2020), “The political coronavirus paradox: Where the virus was worst, voters supported Trump the most”, Time, 11 November.