Commodity and food prices have increased significantly in 2022, as a strengthening of demand post-Covid was exacerbated by Russia’s invasion of Ukraine. Gas in Europe, in particular, traded at record levels. At the same time, gas accounts for around 30% of energy consumption across emerging markets in Europe. Policymakers have used a wide range of measures to mitigate the impact these higher energy and food prices have on households and firms, with most countries taking action of some kind. The strikingly varied nature of policy responses reflects a multitude of social objectives.

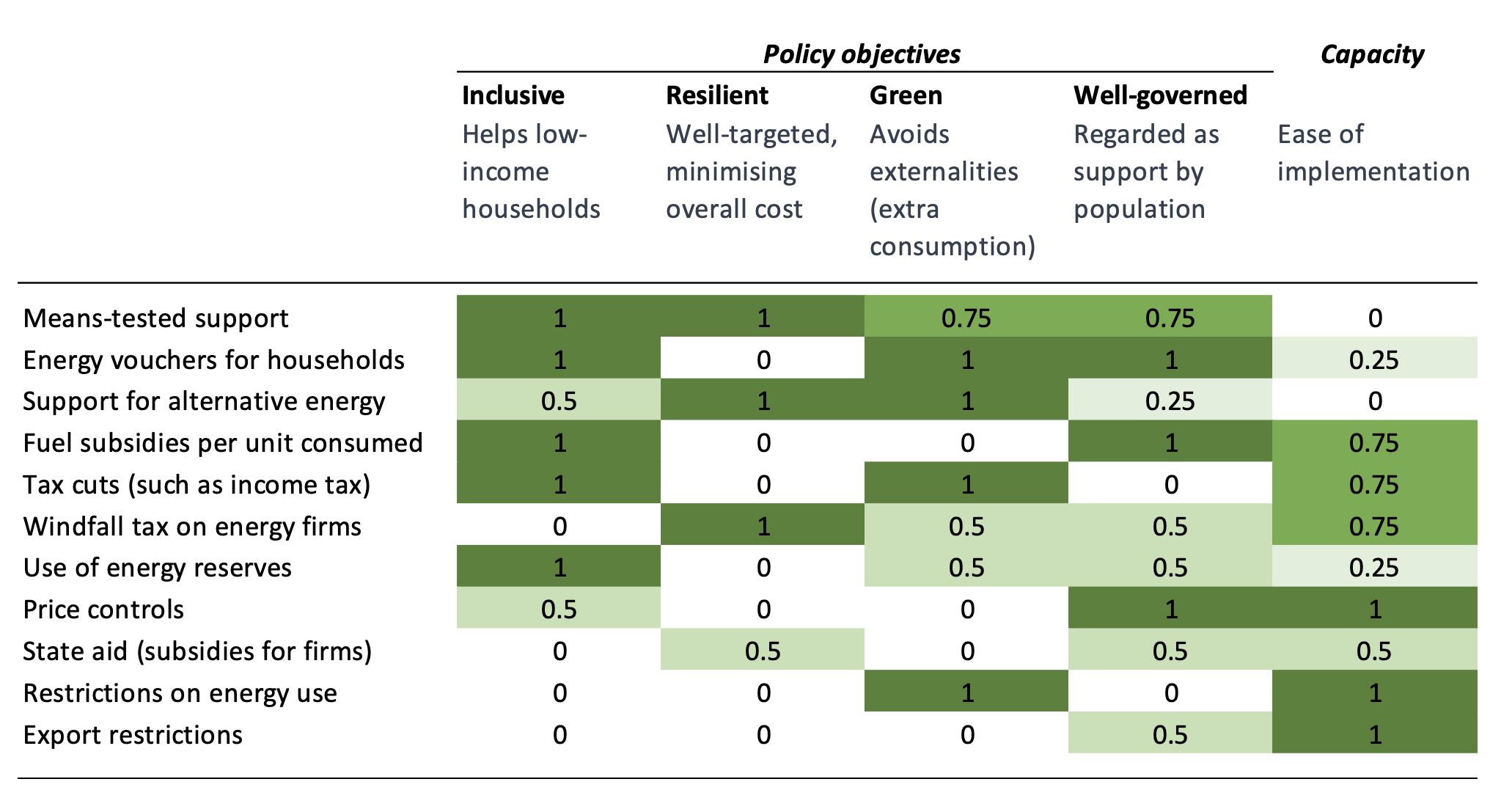

First and foremost, policy measures seek to help the people who are most in need – typically low income households. The overall fiscal cost of such measures is partly a reflection of how well they are targeted, with economies that face more binding fiscal constraints typically choosing to prioritise a reduced fiscal cost. Policymakers may also seek to limit any externalities stemming from fuel and food subsidies (such as increases in energy consumption and associated greenhouse gas (GHG) emissions), in line with green-economy objectives. Measures also differ in terms of both the ease with which they can be communicated to the wider population and their likely reception by voters (which is a question of good governance). The importance of measures’ political appeal may also vary from economy to economy. Finally, some measures are easier to implement, while others require greater administrative capacity. Table 1 provides a summary of how effectively various policies deployed in Emerging Europe and Central Asia can achieve various objectives.

Table 1 Policy responses to higher energy and food prices vary in terms of their effectiveness

Source: Authors.

Note: Effectiveness scores are on a scale from 0 to 1. Measures are ranked by the average policy objective score.

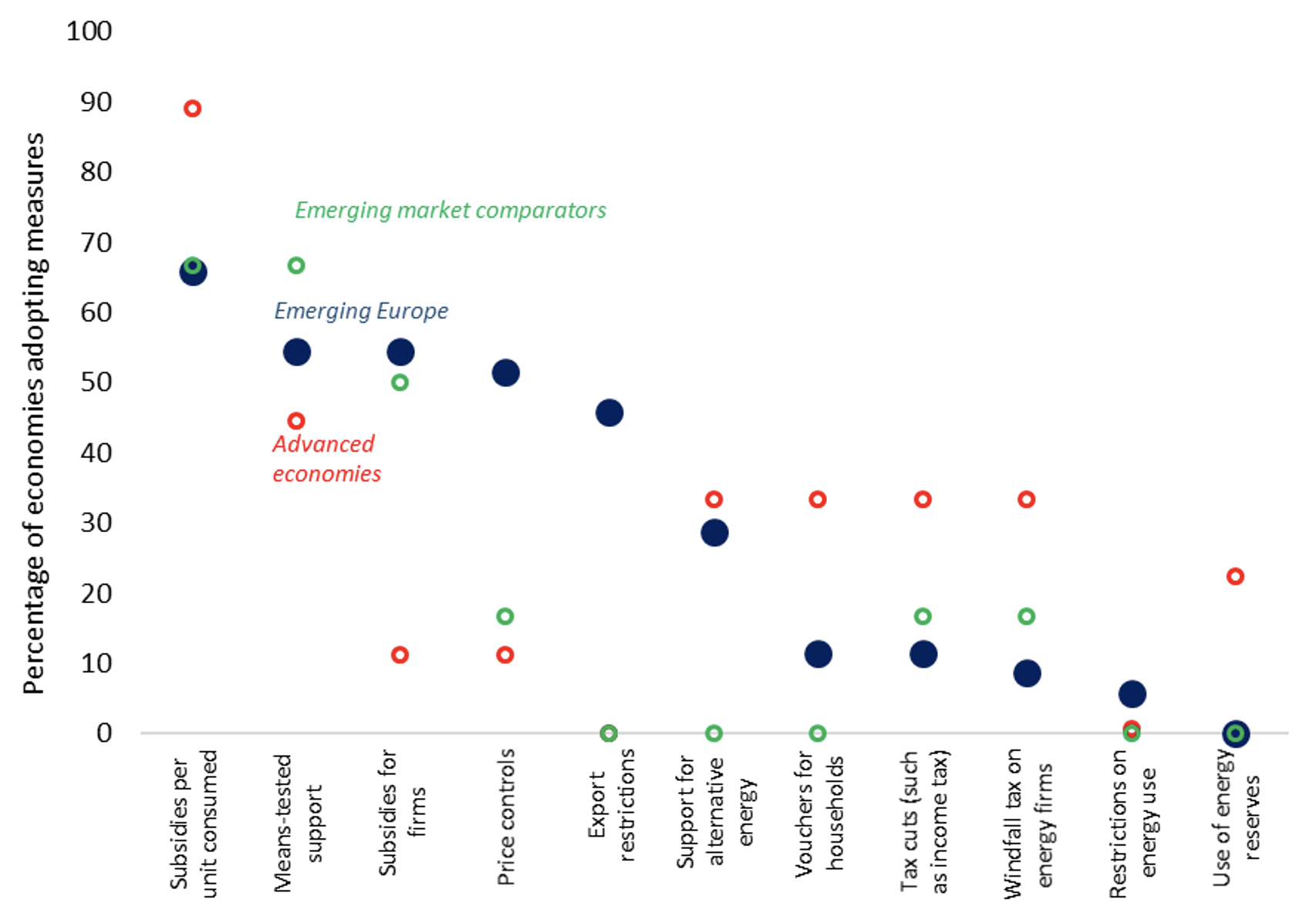

The most common measures are fuel subsidies per unit consumed (per litre of diesel or per kilowatt hour (kWh) of electricity, for instance; see Figure 1). By late July 2022, these had been introduced in 64% of the surveyed emerging market economies and the majority of advanced comparator economies, as well as in selected emerging market comparators.

Figure 1 A wide range of measures have been introduced in response to high energy and food prices

Source: Authors’ calculations.

Note: Here and elsewhere, advanced economy comparators are Canada, Cyprus, France, Germany, Italy, Japan, Sweden, UK, and US. Emerging market comparators are Bangladesh, Brazil, Colombia, Mexico, South Africa, and Thailand. Emerging Europe also includes Central Asia and Egypt, Jordan, Tunisia, Lebanon, and Morocco.

Such subsidies are usually justified by the fact that lower-income households spend larger percentages of their income on food and energy. These measures are relatively easy to implement and communicate. On the other hand, subsidising energy prices encourages overconsumption, making per-unit subsidies environmentally unfriendly. Moreover, while the poor do benefit, pay-outs accrue primarily to better-off customers who consume more energy and food, making subsidies poorly targeted and fiscally costly. In other words, such measures may score highly in terms of inclusion and governance, but poorly on resilience and green impact.

Price controls on food and energy are also common in Emerging Europe and Central Asia, but much less so in advanced economies and emerging market comparators elsewhere, possibly reflecting the history of central planning in the 20th century. For instance, Hungary has capped the prices of various food staples and fuel. Price controls are easy to communicate and implement, but they encourage waste and often result in shortages. Moreover, low-income households may not be able to get hold of price-capped goods in the first place.

Some countries have scaled up means-tested support programmes targeting low-income households. In Poland, for instance, a special allowance for households is expected to provide a maximum of €106 per person per year, depending on income levels, the type of heating, and the number of people in the household. Such means-tested measures are relatively well targeted and may avoid excessive energy usage, depending on their design. For instance, giving a household a voucher (rather than a discount on the price per unit) does not alter the price that the consumer has to pay for an additional unit of electricity. However, reaching out to the households who are most in need requires a relatively high level of administrative capacity. Strong communication may also be required to ensure that the narrower targeting of benefits does not undermine their political appeal.

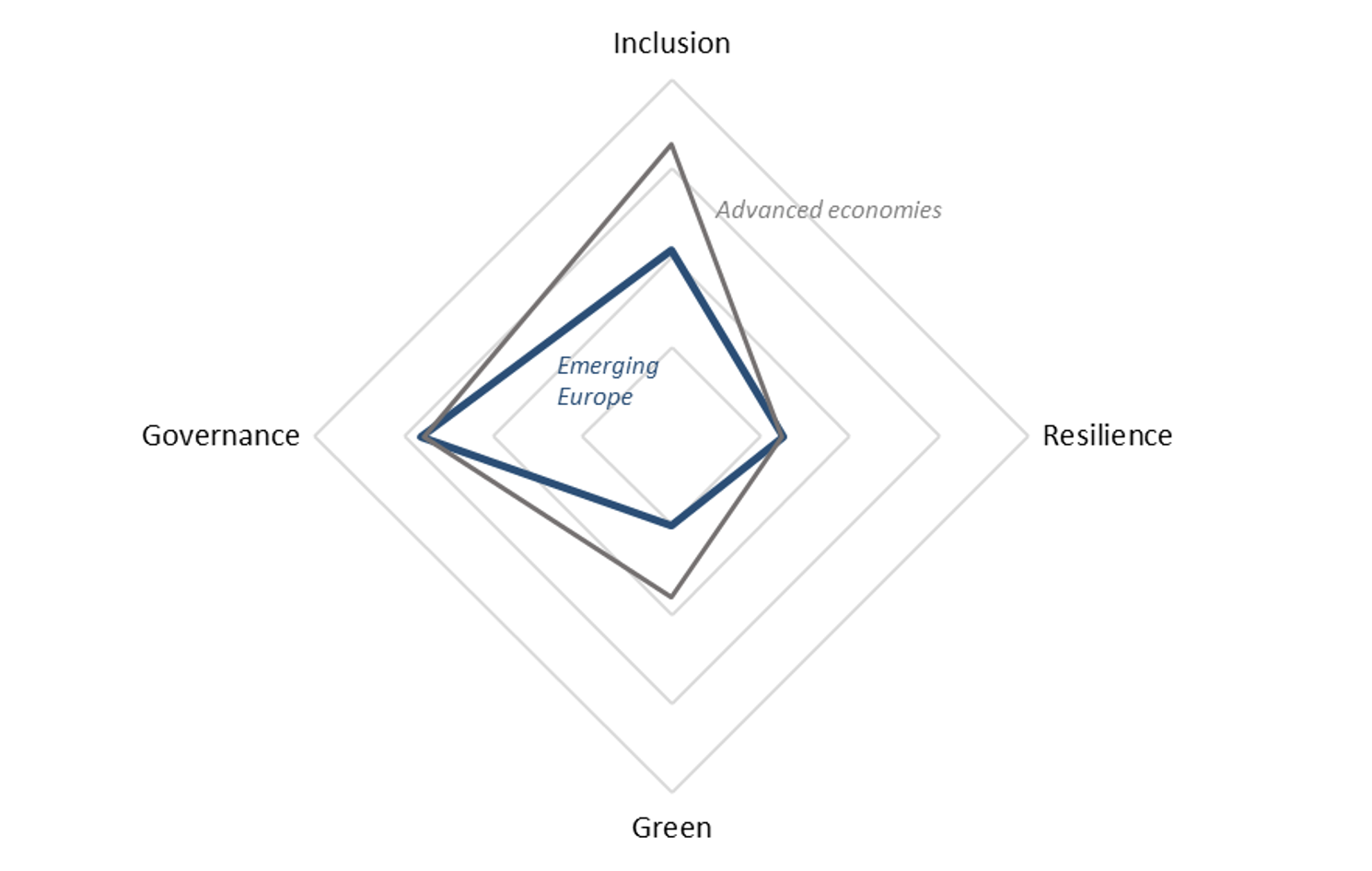

Overall, measures in emerging markets have been less effective – across a range of objectives

Even allowing for differences in policy objectives across countries, responses in Emerging Europe and Central Asia have been less effective than in advanced economies, being less inclusive and less green (see Figure 2).

Figure 2 Policy responses in emerging markets have been less effective than in advanced economies

Source: Authors’ calculations.

Note: For each economy, policies are scored on four different objectives and average scores are calculated across all policies in place.

Policy responses are aligned with measures of progress in various areas of structural reform

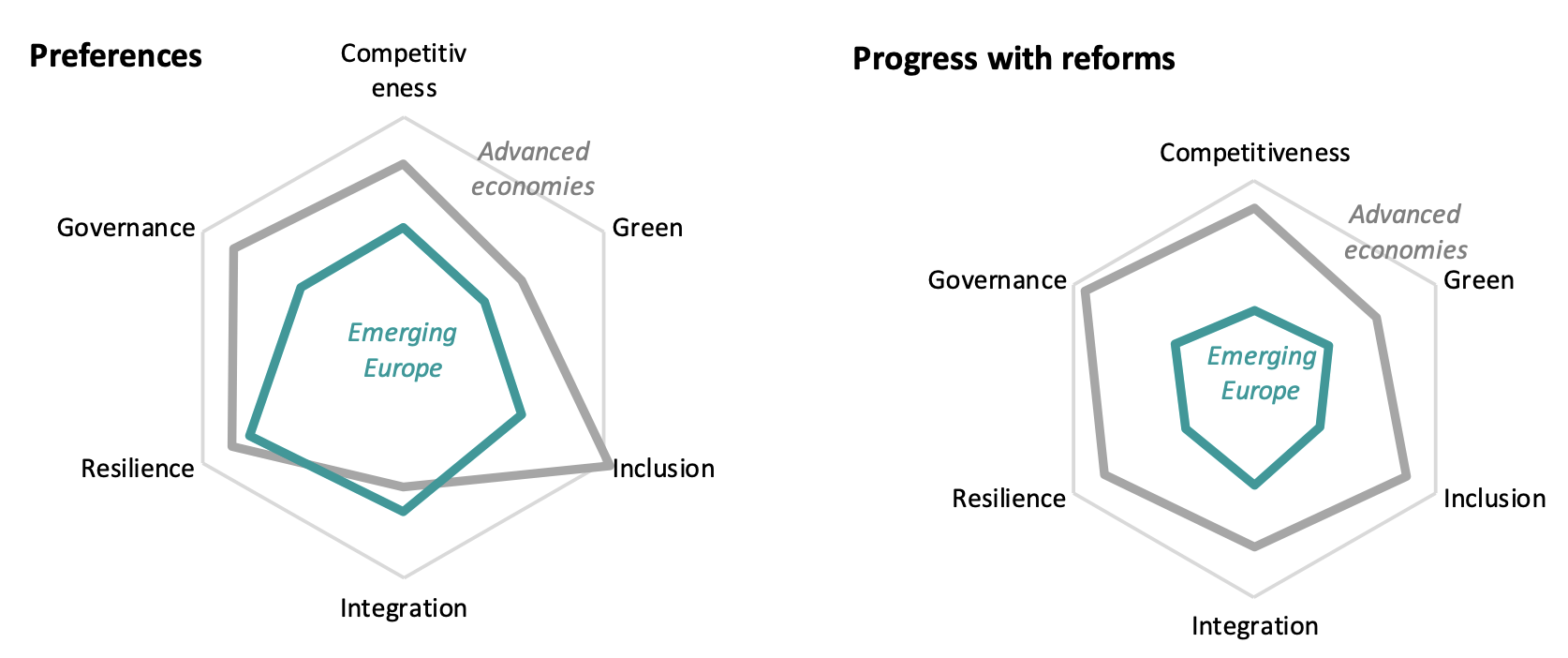

Average policy response scores are also somewhat aligned with differences in progress in structural reform in various areas such as the green economy or inclusion, as measured by the scores compiled annually by the European Bank for Reconstruction and Development (Carruthers et al. 2022). These scores cover six areas (green economy, inclusion, competitiveness, governance, resilience, and economic integration) and range from one to ten (EBRD 2022).

This relationship, in part, reflects the fact that at least a third of policy responses have involved modifying and expanding existing schemes and initiatives (such as means-tested support programmes or subsidies). This leaves the question of what determines differences in those initiatives – and progress in structural reforms – in the first place.

While progress in reform is aligned with citizens’ preferences

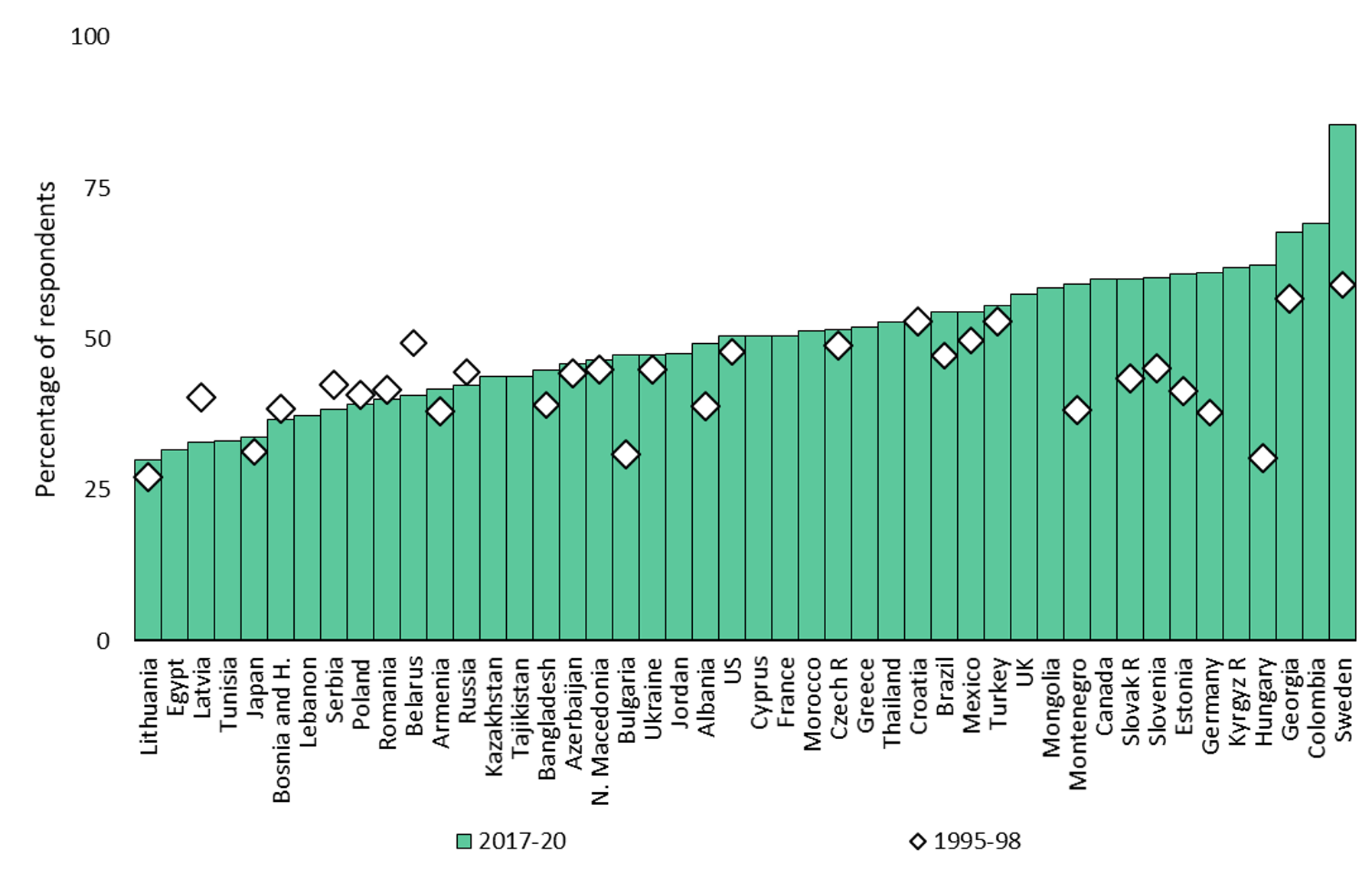

It turns out that progress with reforms is strongly aligned with citizens’ preferences in the respective policy areas, as inferred from the latest round of the World Values Survey, conducted in countries around the world in the period 2017-20 (see Ingelhart et al. 2014, for details of the survey). Where possible, preferences are inferred from questions that involve a trade off between different desirable features of development. For example, respondents are asked to choose between the following statements: “Protecting the environment should be given priority, even if it causes slower economic growth and some loss of jobs” and “Economic growth and creating jobs should be the top priority, even if the environment suffers to some extent”. Answers to questions of these nature were converted to indices ranging from 0 to 1 (Carruthers et al. 2022, EBRD 2022).

Average attitudes with respect to the green economy and other policy priorities vary considerably across countries (see Figures 3 and 4). For example, Emerging Europe and Central Asia stand out in terms of high support for economic integration (consistent with accession to the EU having been a strong anchor for economic reforms, see, for instance, Georgiev et al. 2017). In contrast, support for green and inclusion reforms is considerably weaker in this region.

Figure 3 Support for protecting the environment varies greatly across economies

Source: World Values Survey and authors’ calculations.

Note: Percentage of respondents who agree with the statement “Protecting the environment should be given priority, even if it causes slower economic growth and some loss of jobs”.

Figure 4 Differences in citizens’ preferences are large and aligned with progress with reforms

Source: World Values Survey, EBRD and authors’ calculations.

Note: Based on the 2017-20 surveys or the most recent round available for each economy.

While far from perfect, there is considerable alignment between differences in citizens’ preferences and differences in the progress made with reforms in each area (see Figure 4). The causal link could plausibly run in both directions. Successful reforms could, for example, strengthen people’s support for economic integration or inclusion while the strength of citizens’ preferences could encourage policymakers to undertake reforms in particular areas. At the same time, there are reasons why the relationship between citizens’ preferences and progress with reforms is far from perfect. These include imperfectly measured preferences; the short-term nature of political cycles; and special interests that distort the incentives of elected officials (Milesi-Ferretti and Spolaore 1994).

References

Carruthers, A and A Plekhanov (2022), “Attitudes, beliefs and reforms”, EBRD working paper, forthcoming.

EBRD (2022), Business Unusual, Transition Report 2022-23.

Georgiev, Y, P Nagy-Mohacsi and A Plekhanov (2017), “Structural reform and productivity growth in Emerging Europe and Central Asia”, Asian Development Bank Economics Working Paper No. 523.

Inglehart, R, C Haerpfer, A Moreno, C Welzel, K Kizilova, J Diez-Medrano, M Lagos, P Norris, E Ponarin and B Puranen (2014), “World Values Survey”, JD Systems Institute.

Milesi-Ferretti, G M and E Spolaore (1994), “How cynical can an incumbent be? Strategic policy in a model of government spending”, Journal of Public Economics 55(1): 121-140.