The size of fiscal multipliers has been the subject of intense debate in the last decade, especially in light of the large fiscal support implemented by governments to mitigate the effects of the recent COVID crisis (Murphy et al. 2021, Deb et al. 2022, Rossi et al. 2022). Cross-country studies on the effectiveness of fiscal stabilisation policies agree that fiscal multipliers are smaller in developing countries (Kraay 2012, Ilzetzki et al. 2013), in those characterised by high levels of public debt (Huidrom et al. 2020) and low institutional quality. The role of other factors, such as financial and trade openness, financial development, and the exchange rate regime, is more controversial (Chian Koh 2017, Ramey 2019).

In our recent work (Colombo et al. 2024), we argue that another important factor affecting the size of the fiscal multipliers is informality. While previous research has looked at the role of informality in affecting the effect of fiscal policy, it has mostly focused on corruption and tax evasion investigating a limited set of countries. For example, Pappa et al. (2015) document that accounting for tax evasion improves the estimates of fiscal multipliers in a group of OECD countries, and provide evidence that spending cuts induce a reallocation of production towards the formal sector. Dellas et al. (2017) argue that the large forecast errors associated to the fiscal consolidation in Greece can be explained by neglecting the informal sector. Basile et al. (2016) find that in Italy public expenditure shocks cause a reduction in the share of unreported income. Going beyond advanced economies, Lemaire (2020) shows that fiscal consolidation leads to larger output contractions in the Latin American countries characterised by a lower informal sector.

We contribute to the literature by providing the first systematic analysis of the role of informality in shaping the (official) output effects of public expenditure shocks for a sample of 142 developed and developing economies. In addition, we provide theoretical evidence of a key channel through which informality affects the fiscal multiplier.

To identify public expenditure shocks, we follow the approach of Auerbach and Gorodnichenko (2013), and compute the forecast errors for the growth rate of government spending (using the IMF’s World Economic Outlook data) that are then purged of any predictable components by projecting them on lags of several macroeconomic variables (output, government spending, real exchange rate, and inflation) and also on forecasts of key economic outcomes (such as output, consumption, and investment). The residuals of this projection are taken as the fiscal shocks that we use to instrument government expenditures to GDP and compute the cumulative multiplier as in Ramey and Zubairy (2018).

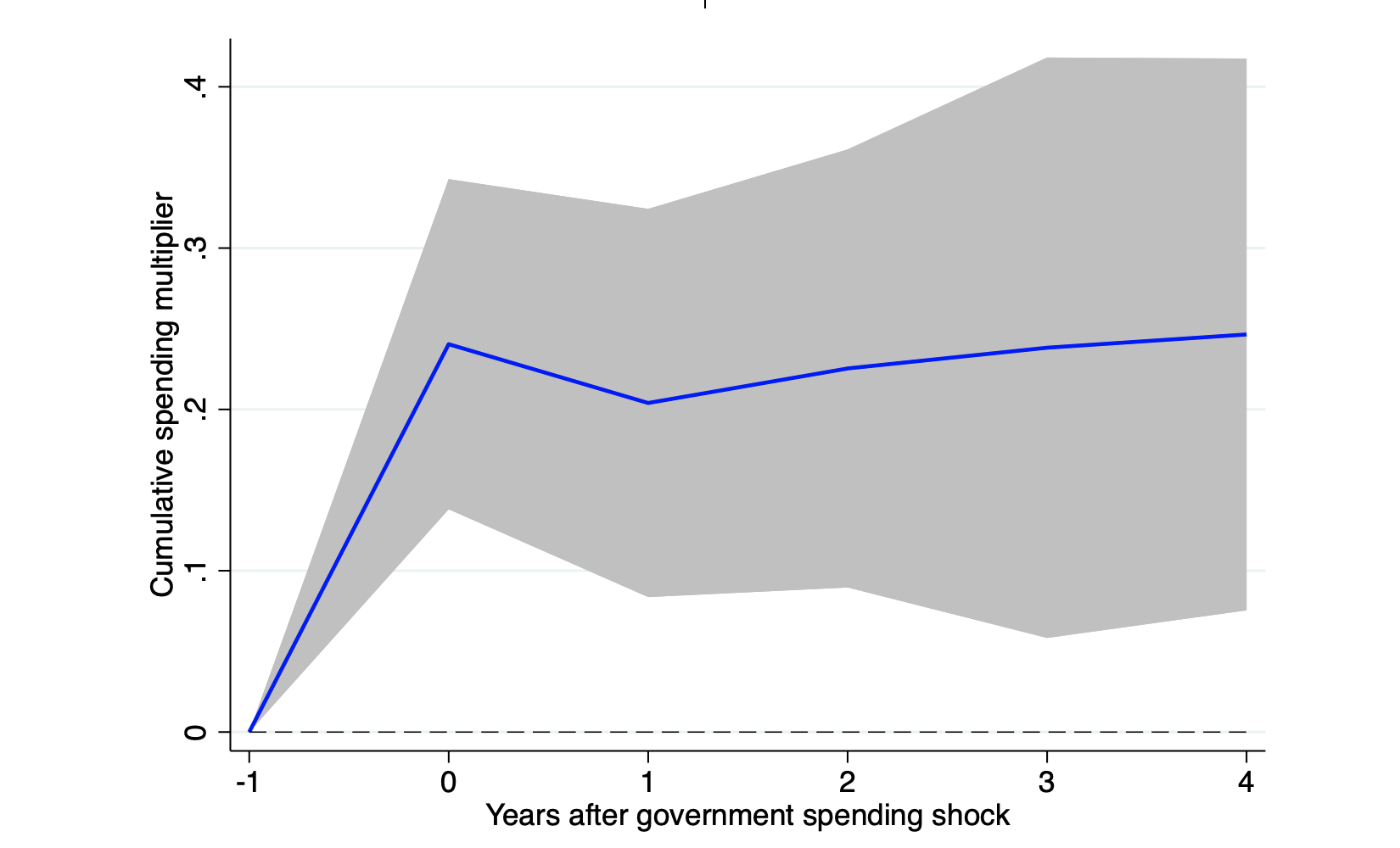

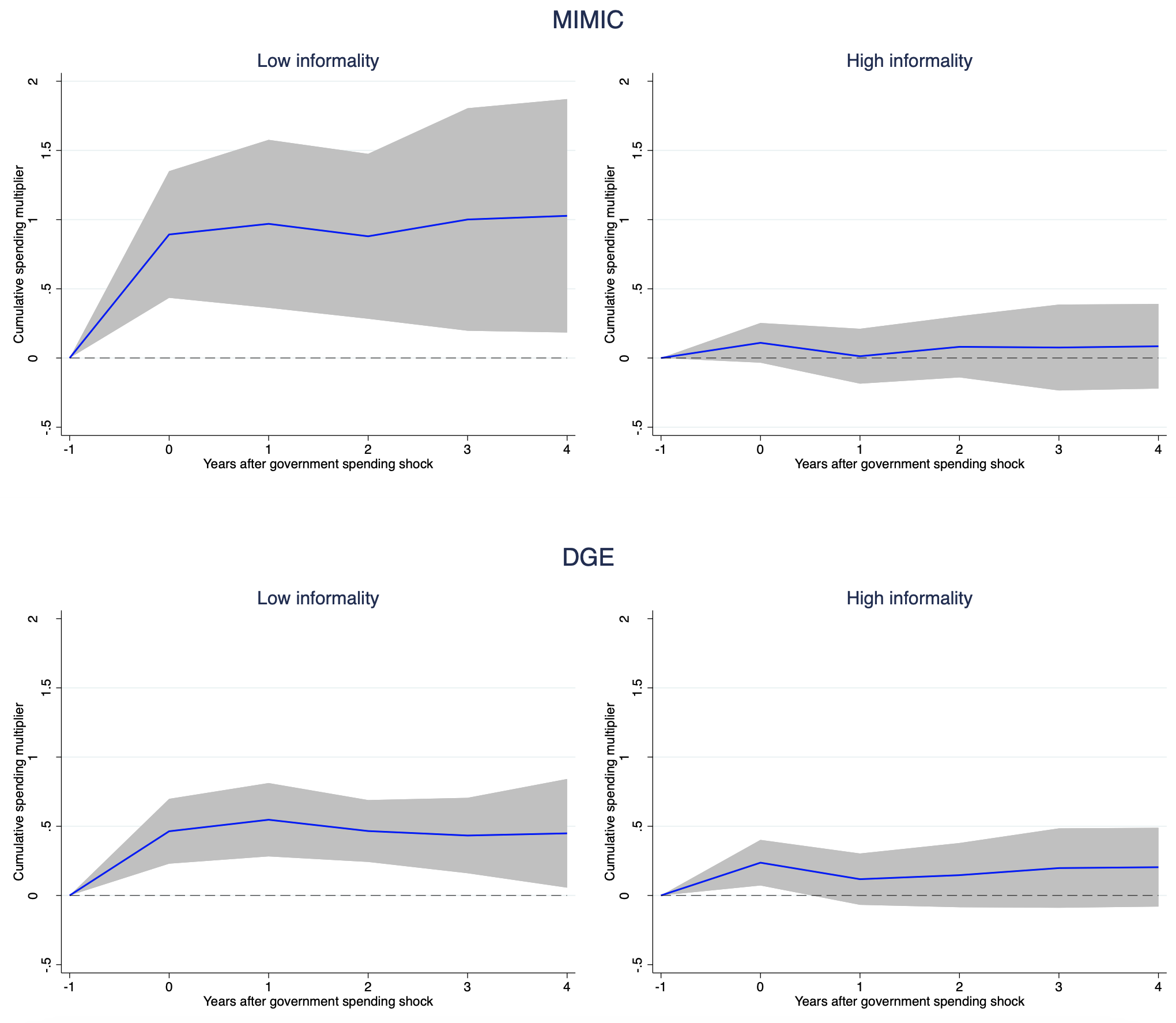

Figure 1 shows the average cumulative multiplier at each time horizon (year). In line with the existing literature, we find that expansionary fiscal policy leads to a significant increase in output over the four-year period following the shock. The implied cumulative multiplier is about 0.25 on impact, and it remains fairly constant up to four years after the shock. However, we show that this average effect masks significant heterogeneity across countries. Using two different measures of the shadow economy – Medina and Schneider’s (2018) MIMIC estimates and the DGE-based measure by Elgin and Oztunali (2012) and Elgin et al. (2019) – our results suggest that countries characterised by high informality tend to have a significantly lower fiscal multiplier (Figure 2).

Figure 1 Cumulative multiplier: Unconditional

Note: The chart shows the impulse response functions and the associated 90 percent confidence bands estimated using and unbalanced sample of 142 countries over the period 1995-2015; t = 0 is the year of shock.

Figure 2 Cumulative multiplier: The role of the shadow economy

Note: The chart shows the impulse response functions and the associated 90 percent confidence bands estimated using and unbalanced sample of 142 countries over the period 1995-2015; t = 0 is the year of shock. Shadow economy estimates are from MIMIC and DGE models.

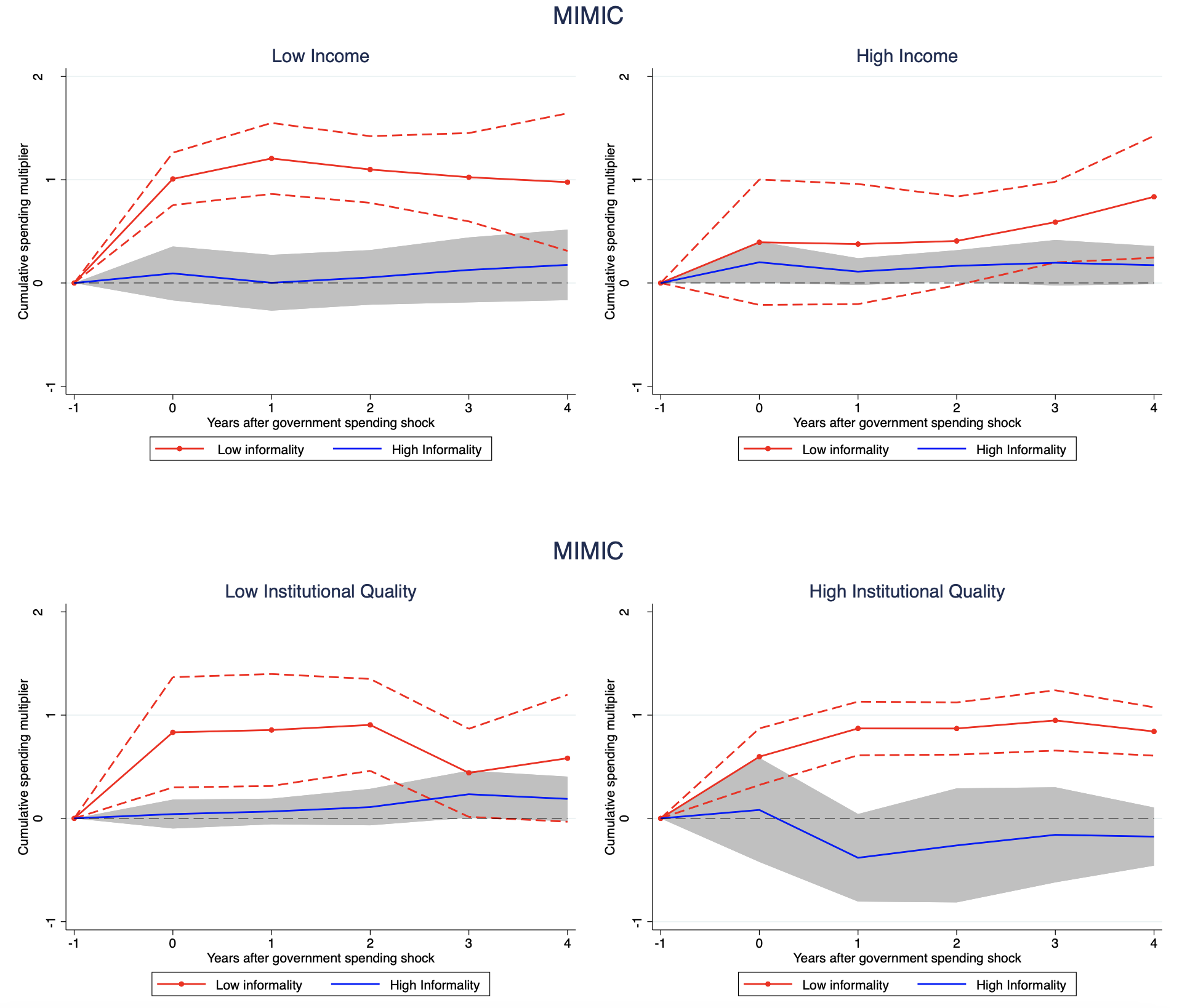

This finding is fully confirmed when we control for other country characteristics and, more importantly, also holds irrespective of the level of development and the degree of institutional quality – characteristics typically highly correlated with informality (Figure 3).

Figure 3 The role of the shadow economy versus the level of economic development and institutional quality

Note: The chart shows the impulse response functions and the associated 90 percent confidence bands estimated using and unbalanced sample of 142 countries over the period 1995-2015; t = 0 is the year of shock. Shadow economy estimates are from MIMIC. Results based on DGE are very similar and broadly unchanged. They can be found in Colombo et al. (2024)

To identify the key transmission channel through which informality affects the magnitude of the fiscal multiplier – and consistent with the empirical evidence – we develop a theoretical model in which the effect of fiscal shocks is only determined by the size of the informal sector, and not by the quality of institutions or other standard features that distinguish developing and advanced economies.

In particular, our two-sector New Keynesian model shows that the public expenditure shock raises the relative demand for formal goods and causes the appreciation of their relative price. This, in turn, triggers a reallocation of private expenditure towards unofficial goods, weakening the response of official output to the shock. Crucially the strength of this basic mechanism increases with the degree of informality in the economy, and it is sufficient to explain a substantial part of the different multipliers estimated.

Our results have important implications. First, neglecting the strong response of the informal sector downplays the effectiveness of public expenditure as a stabilisation tool in countries characterised by large informal sectors. Second, the presence of a large informal sector unambiguously undermines governments’ ability to implement stabilisation policies, because the limited response of the official sector requires tighter tax policies to raise the revenues needed to preserve fiscal solvency. Our model has also implications for tax policy. In standard models with homogeneous goods, a VAT tax generally acts on the supply side by incentivising firms to use informal production activities. In our model, consumer demand is also affected and the propagation mechanism is reinforced. A tax on the return to capital has a reallocating effect that, in our case, would be weakened by the fall in the relative price of formal goods. An analogous, albeit smaller effect, would follow a change in the tax on labour income.

References

Auerbach, A J and Y Gorodnichenko (2013), “Fiscal Multipliers in Recession and Expansion”, in in A Alesina and F Giavazzi (eds), Fiscal Policy after the Financial Crisis, University of Chicago Press.

Basile, R, B Chiarini, G De Luca and E Marzano (2016), “Fiscal multipliers and unreported production: evidence for Italy”, Empirical Economics 51: 877-896.

Chian Koh, W (2017), “Fiscal multipliers: new evidence from a large panel of countries”, Oxford Economic Papers 69(3): 569-590.

Colombo, E, D Furceri, P Pizzuto and P Tirelli (2024), “Public Expenditure Multipliers and Informality”, European Economic Review, 104703.

Deb, P, D Furceri, J D Ostry, N Tawk and N Yang (2022), “The effects of fiscal measures during COVID-19”, VoxEU.org, 2 February.

Dellas, H, D Malliaropulos, D Papageorgiou and E Vourvachaki (2017), “Fiscal policy with an informal sector”, CEPR Discussion Paper 12494.

Elgin, C, A Kose, F Ohnsorge and S Yu (2019), “Shades of grey: Measuring the informal economy business cycle”, Seventh IMF Statistical Forum.

Elgin, C and O Oztunali (2012), “Shadow economies around the world: model-based estimates”, Bogazici University Department of Economics Working Paper 5(2012).

Huidrom, R, M A Kose, J J Lim, and F L Ohnsorge (2020), “Why Do Fiscal Multipliers Depend on Fiscal Positions?”, Journal of Monetary Economics 114: 109–25.

Ilzetzki, E, E G Mendoza and C A Végh (2013), “How big (small?) are fiscal multipliers?”, Journal of Monetary Economics 60(2): 239-254.

Kraay, A (2012), “How large is the government spending multiplier? Evidence from World Bank lending”, The Quarterly Journal of Economics 127(2): 829-887.

Lemaire, T (2020), “Fiscal Consolidations and Informality in Latin America and the Caribbean”, Banque de France Working Paper 764.

Medina, L and M F Schneider (2018), “Shadow economies around the world: what did we learn over the last 20 years?”, IMF Working Paper no. 18/17

Murphy, D, Y Gorodnichenko, P McCrory and A Auerbach (2021), “What Covid-19 teaches us about fiscal multipliers”, VoxEU.org, 23 December.

Pappa, E, R Sajedi and E Vella (2015), “Fiscal consolidation with tax evasion and corruption”, Journal of International Economics 96(S1): 56–75.

Ramey, V A and S Zubairy (2018), “Government spending multipliers in good times and in bad: evidence from US historical data”, Journal of Political Economy 126(2): 850-901.

Ramey, V A (2019), “Ten Years After the Financial Crisis: What Have We Learned from the Renaissance in Fiscal Research?”, Journal of Economic Perspectives 33(2): 89–114.

Rossi, B, Y Wang and A Inoue (2022), “Why fiscal multipliers estimates change over time and what determines their magnitude”, VoxEU.org, 14 April.