Imbalances in sex ratios often emerge in the aftermath of wars and civil conflicts. Men are more likely to go to war and die. As a consequence, there is often a scarcity of males after conflicts. This shortage impacts economic variables through different channels. Several papers have evaluated these effects on developed countries – specifically, exploiting WWI and WWII and focusing on labour force participation, marriage markets, and out-of-wedlock births.

Acemoglu et al. (2004) and Fernandez et al. (2004) find that after WWII female labour force participation increased permanently and suggest changes in gender norms as the mechanisms for higher participation. Using WWI, Boehnke and Gay (2022) and Gay (2021) show that, after the war, female labour force participation increased in France through intergenerational transmission. Using the same event and country, Abramitzky et al. (2011) find that women were less likely to marry and that the proportion of out-of-wedlock births was higher after the conflict. Knowles and Vandenbroucke (2019) also work with French data and find that, after WWI, female marriage probabilities increased. Bethmann and Kvasnicka (2013) find that out-of-wedlock births increased in Germany due to the scarcity of men due to WWII. Using the same event, but focusing on Russia, Brainerd (2017) finds that marriage and fertility rates decreased and out-of-wedlock births increased after the War.

In this column, we focus instead on a conflict that took place in a developing country: The War of the Triple Alliance (1864-1870). This war generated one of the largest sex ratio shocks in history. The struggle pitted Paraguay against an alliance composed of Brazil, Argentina, and Uruguay and is considered one of the most destructive conflicts in modern times (Pinker 2011). It is estimated that approximately 60% of Paraguay’s population died in the conflict (Whigham and Potthast 1999) and some historians argue that up to 90% of Paraguayan men died. This generated an extreme sex ratio imbalance (men per woman) of 0.3 – that is nearly four women per man. For comparison, the sex ratio analysed after WWI was 0.7 and, post WWII, was 0.9.

In Alix-Garcia et al. (2022), we make three contributions to the historical conflict literature. First, we study a war that took place a longer time ago than other conflicts, thus we can analyse short, medium, and long-term outcomes. Second, this war generated an extreme sex ratio which had not been seen in other conflicts studied. Finally, we focus on a developing country, complementing the evidence for more developed nations. In addition, we assess quantitatively the long-run impact of the largest interstate war in Latin America. Although this conflict has received considerable attention and relevant qualitative discussions in the historical literature, there has not been a quantitative evaluation of the war’s long-standing effects.

Biased sex ratios will likely continue as a consequence of interstate wars and civil conflicts, therefore is relevant to evaluate the short- and long-run effects of these imbalances and learn from history.

The Triple Alliance War

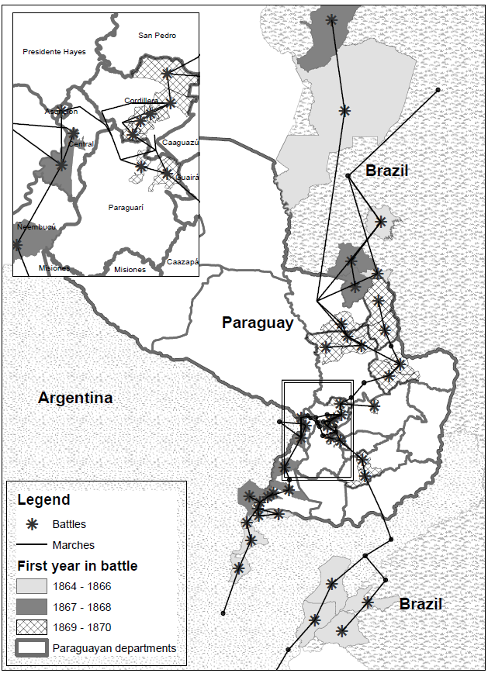

The Triple Alliance War, which is also known as The Paraguayan War, lasted from 1864 to 1870. It is considered the bloodiest and most damaging interstate conflict in Latin America and, possibly, in the modern era (Bethell 1996, Pinker 2011). The conflict emerged as a consequence of clashing economic interests, evolving power structures, and misjudgment. Paraguay invaded Uruguay as a response to Brazil’s invasion of Uruguay. Then, Paraguay declared war on Brazil. Argentina denied permission to Paraguay to cross through its territory to go to Uruguay – consequently, Paraguay declared war on Argentina as well. Uruguay, after a change of government to a political party aligned with Brazil and Argentina, joined in an alliance with these countries against Paraguay (Bethell 1996). The battles took place in Paraguay, Argentina, and Brazil, but mostly affected Paraguay. Figure 1 depicts battles and marches.

The short-term devastation was evident. The allies conducted a census when the war finished and found 221,079 people remaining in Paraguay: 28,746 men, 86,079 children, and 106,254 women (Potthast-Jutkeit 1991). Historians’ estimates of sex ratios after the war diverge: Washburn (1871) argues there were seven women per man, Potthast (2005) argues there were four women per man, and Ganson (1990) argues there were three women per man. Even if we take the lowest ratio, there is no previous record of sex disparities at that level. However, this imbalance converged to unity relatively quickly. According to the 1886 census, there were 1.4 women per man. Moreover, the 1899 census reported a sex ratio of 1.16. In Argentina and Brazil, the effect on sex imbalances was comparatively small. Unlike Paraguay’s army, allied soldiers accounted for a smaller share of their populations. For example, Brazilian soldiers and slaves were brought from across the whole nation to the inhabited border areas. Hence, comparisons across the borders help to isolate the effects of biased sex ratios from the effect of the war.

Figure 1 Timeline and spatial extent of war

Notes: We digitised information on the location of battles and starting and ending points of marches described by Jaeggli and Bordon (2010).

Identification strategy

To evaluate the effect of imbalances in sex ratios, we exploit two sources of variation. First, we use the discontinuity in the perimeter between Paraguay and bordering municipalities in Argentina and Brazil. Second, we conduct a within-Paraguay analysis and evaluate the effect of the intensity of the conflict using distance to battles or march lines as intensity measures. We use both strategies to examine the immediate, medium-, and long-term effects of the war. The advantage of the within Paraguay analysis is that institutions are constant, but we sacrifice external validity. On the other hand, the cross-border analysis exploits extremely large differences in sex ratios. Besides, the border municipalities share cultural characteristics with Paraguayan society, including the historical presence of Guaraní people (the dominant indigenous group in the area). In fact, some of these were disputed areas lost by Paraguay after the conflict. Moreover, the frontier between Paraguay and Argentina was not delimited until 1876. The disadvantage is that, when crossing an international border, formal institutions change. To address this, most of the cross-country analysis only compares bordering provinces and municipalities to provide better counterfactuals for Paraguay.

Main findings

Short-term effects: Sex ratios

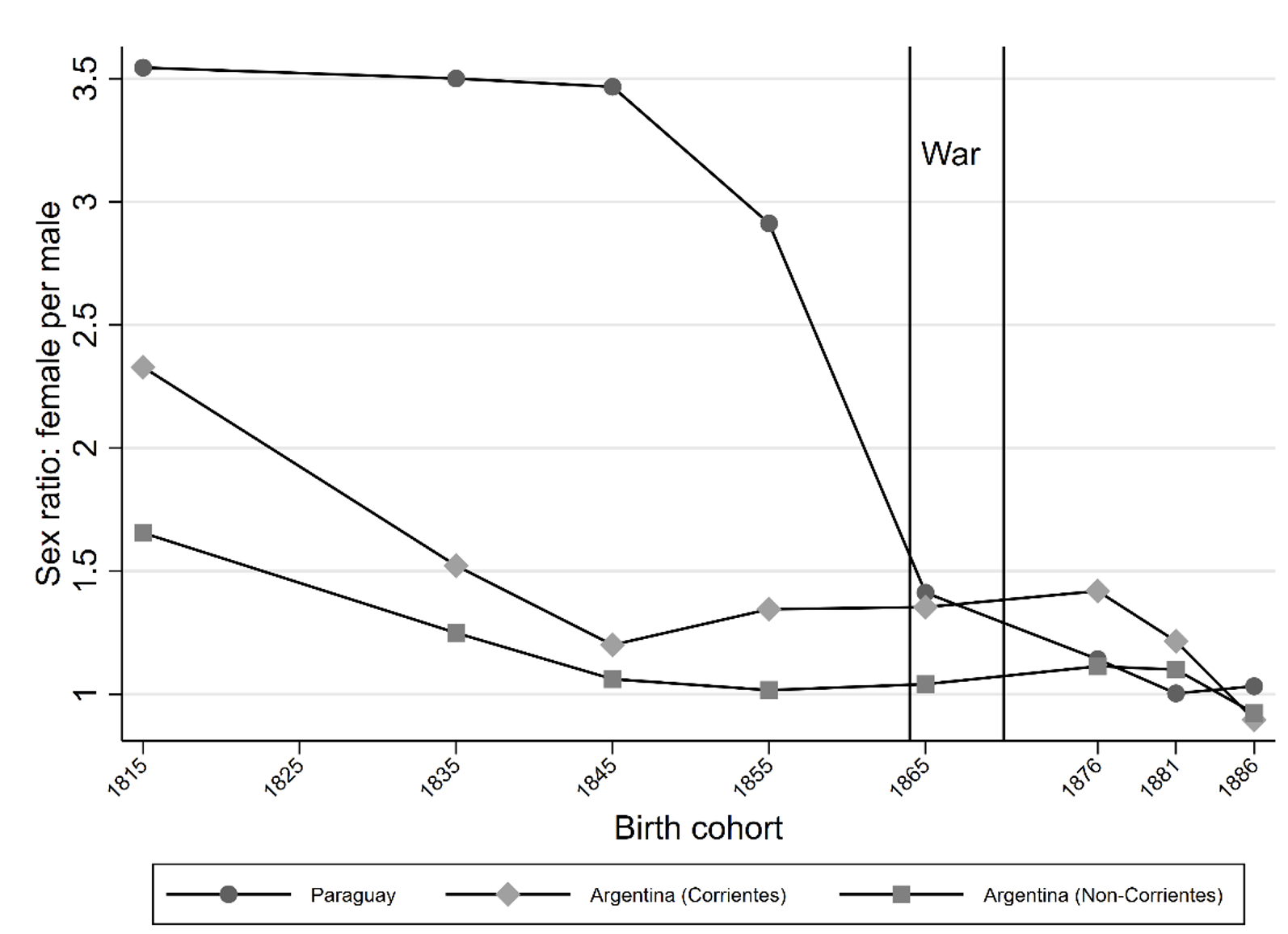

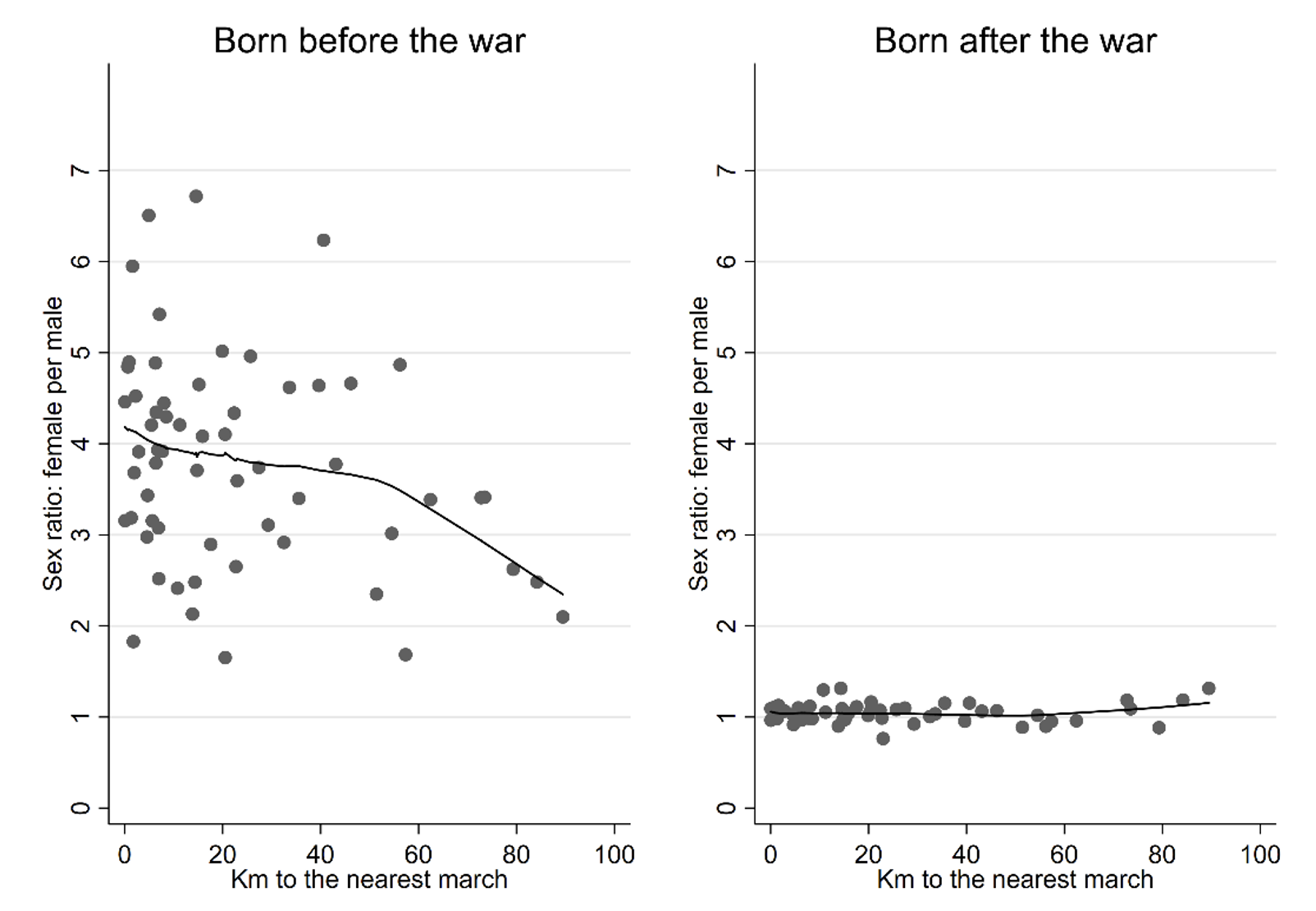

We use the 1886 Paraguayan and 1895 Argentinean censuses to analyse the postwar effects (Figure 2). We split the data for Argentina and show data from Corrientes – the bordering province with data available after the war – and from the rest of the country. In Paraguay, the ratio of women to men for cohorts born between 1836 and 1845 (aged 15-24 at the beginning of the war) is 3.5. For the same group, in Corrientes it is 1.25 and for the rest of Argentina it is 1.1. For cohorts born after the conflict, the ratio approaches unity. The within Paraguay econometric results show that, in areas closer to march lines, the ratio of women to men after the war was higher for cohorts born after the war. For those born after the conflict, the relationship between distance to marches and sex ratios is almost flat (Figure 3). Hence, the evidence supports that the war generated biased sex ratios.

Figure 2 Paraguayan and Argentinean population sex ratio by birth cohort

Notes: Data from Paraguay's 1886 census and Argentina's 1895 census. The year on the x-axis represents the end of the birth cohort. The birth cohorts are born before 1816, 1816-1835, 1836-1845, 1846-1855, 1856-1865, 1866-1876, 1877-1881, and 1882-1886.

Figure 3 Relationship between distance to march line and sex ratio in Paraguay

Notes: Data from Paraguay's 1886 census. The curves are from locally weighted regressions of sex ratio on distance to the nearest march line at the municipality level. The bandwidth is set at 0.8. The sample drops Asunción, the Paraguayan Chaco, and small municipalities where the population among people born either before the war or after the war was less than 200 people. Born before the war means born before 1856, and born after the war means born after 1865.

Short-term effects: Out-of-wedlock births

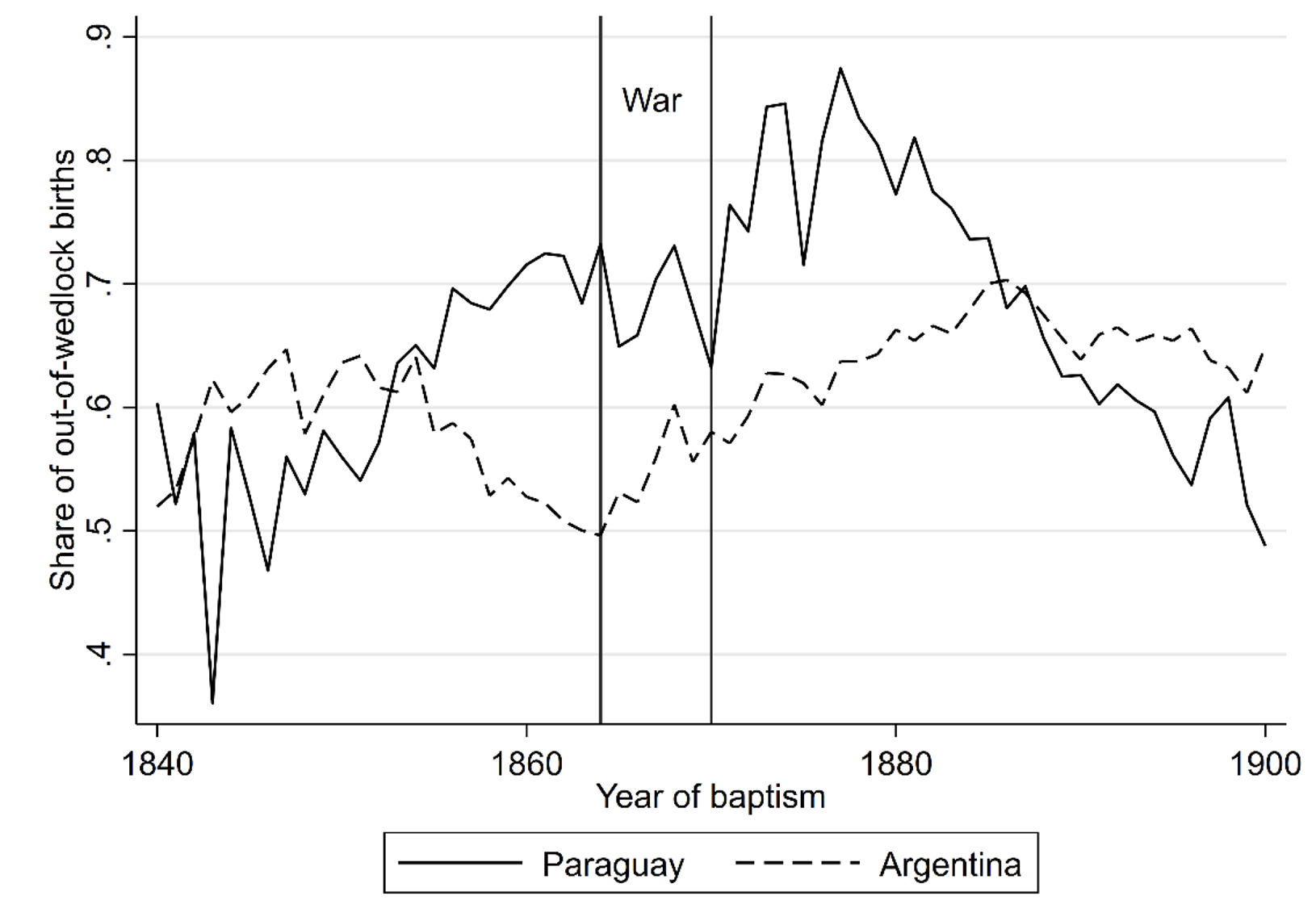

Using baptismal data from 1840 to 1900, we analyse the prevalence of out-of-wedlock births. Compared to Argentina and Brazil, Paraguay historically had higher rates of out-of-wedlock births. However, Figure 4 shows that just after the conflict, the share of out-of-wedlock births jumped in Paraguay. If we compare this to Corrientes (the only neighbouring province for which we have data in this period), the effect continues to be strong. Out-of-wedlock births increased after the conflict, with a larger increase in Paraguay. Rates in Paraguay approached Argentinean rates in the subsequent decades. Similar results hold for the within Paraguay analysis: areas closer to battles or marches had a higher share of out-of-wedlock births after the war.

Figure 4 Out-of-wedlock birth rates across Paraguay and Argentina

Notes: Data from baptismal church records between 1840 and 1900. Sample includes all of Paraguay and Argentine municipalities within 100 km of the border. Sample excludes municipalities reporting their first baptism after 1840 and excludes years with fewer than ten baptisms nationally.

Medium-term effects: Female education

We evaluate female educational outcomes in the medium term in a within Paraguay analysis. In particular, in each municipality, we build the student sex ratio and teacher sex ratio using the 1887 Paraguayan census – the data on teacher sex ratios is the only evidence that measures female labour for participation at the end of the 19th century. We find that, in municipalities more affected by the war, the share of female students and female teachers was higher after the conflict. This difference is not mechanical, as students in 1887 were born after the war, and the sex ratio for individuals born after the war was close to unity.

Long-term effects: Cross-border analysis

Using contemporary data, we focus on the persistence of the temporarily biased sex ratios registered in the aftermath of the war. We compare modern Paraguay to modern neighbouring areas in Brazil and Argentina. Our results indicate that in Paraguay today, households are more likely to be headed by a woman. In addition, Paraguayan women are more likely to raise a child without a partner – however, Paraguayan men are less likely to do so, compared to Argentinean and Brazilian men. For educational outcomes, we find that Paraguayan women are relatively less educated than women across the border. This challenges the idea that biased sex ratios after the conflict increased female education. But, the result might be driven by the weak labour market of Paraguay relative to its neighbours. For employment, we find that men in Paraguay are more likely to be employed than those in neighbouring areas of Argentina and Brazil. But, Paraguayan women are less likely to be employed – in contrast to studies finding long-term increases in female labour participation after both WWI and WWII in Europe. This result could be explained by the fact that women working on their own farms do not consider and report themselves as employed. Another explanation might be that women who are raising children by themselves are less likely to be employed – as the share of single mothers is higher in Paraguay. We explore these outcomes further in the within-country analysis next.

Long-term effects: Within-Paraguay analysis

For the within Paraguay analysis, we find that households located closer to a march line are more likely to be headed by a woman than those located more than 30km away. In addition, women living closer to a march line are significantly more likely to be single and living with their child. An alternative explanation for the high levels of out-of-wedlock childbearing is that it was actually driven by particular features of the Guarani. In the Guarani culture, single mothers and women working in agriculture were common. We address this potential justification and find that the Guarani culture did not drive those results and the effects are caused by the skewed sex ratios after the war. Women are less likely than men to have completed primary education in Paraguay, but the disadvantage is smaller closer to march lines. In the previous subsection, we saw that women were less likely to be employed in Paraguay. However, the within Paraguay results show that women living close to historical battles or march lines are more likely to be employed, compared to those living farther away. They also seem to have slightly better educational outcomes in these historical conflict locations. Hence, it is likely that the within Paraguay results reflect the true impact of biased sex ratios because they take into account national labour market features.

Mechanisms

We explore the cultural mechanism behind the persistent outcomes observed. Gender norms appear to be driving the results. We find that both men and women have a more positive attitude towards women’s right to work the closer to march lines they live. In addition, the literature suggests that gender-related labour force participation norms could pass from parents to their children (Fernandez et al. 2014). The persistence literature also suggests that gender norms could be less persistent in more open and modern environments and stronger in families with indigenous traditions. We test for both suggestions and do not observe any evidence supporting these claims.

Conclusion

The War of the Triple Alliance was the most devastating conflict in Paraguayan history. Beyond its immediate devastation, the war had significant demographic and socioeconomic effects in the short, medium, and long term. In the short term, the cross-border results show that after the war, Paraguay generated an unprecedented sex ratio imbalance – which approached unity relatively quickly – and higher out-of-wedlock births. The within Paraguay results show that municipalities more affected by the war had more skewed sex ratios and out-of-wedlock births. In the medium term, female educational outcomes increased in areas more affected by the conflict. The long-term results indicate that females living in areas more exposed to biased sex ratios are more likely to be raising a child without a partner today and modern households are more likely to be headed by a woman. Within Paraguay, females living closer to battles or march lines are more likely to be educated and employed, and individuals of both sexes believe more strongly in the value of equal labour markets, suggesting the importance of gender norms. The echoes of a war that occurred more than a century ago are still present today. These results give us a deeper comprehension of Paraguay’s uncommon standing in the region. In addition, they can inform our thinking about present-day conflicts and crises worldwide and the effects of skewed sex ratios that emerge as a consequence – especially in developing countries. These events are likely to alter gender norms and effects can last for generations, long after the official ceasefire.

References

Abramitzky, R, A Delavande and L Vasconcelos (2011), “Marrying up: The role of the sex ratio in assortative matching”, American Economic Journal: Applied Economics 3(3): 124-157.

Acemoglu, D, D H Autor and D Lyle (2004), “Women, war, and wages: The effect of female labor supply on the wage structure at midcentury”, Journal of Political Economy 112(3): 497-551.

Alix-Garcia, J, L Schechter, F Valencia Caicedo and S J Zhu (2022), “Country of Women? Repercussions of the Triple Alliance War in Paraguay”, Journal of Economic Behavior and Organization, forthcoming.

Bethell, L (1996), The Paraguayan War (1864-1870), London: Institute of Latin American Studies.

Bethmann, D and M Kvasnicka (2013), “World War II, missing men, and out-of-wedlock childbearing”, Economic Journal 123(567): 162-194.

Boehnke, J and V Gay (2022), “The missing men: World War I and female labor force participation”, Journal of Human Resources 57(4): 1209-1241.

Boggiano, B (2021), “Long-term effects of the Paraguayan War (1864-1870) on intimate partner violence”, Working Paper.

Brainerd, E (2017), “The lasting effect of sex ratio imbalance on marriage and family: Evidence from World War II in Russia”, Review of Economics and Statistics 99(2): 229-242.

Fernandez, R, A Fogli and C Olivetti (2004), “Mothers and sons: Preference formation and female labor force dynamics”, Quarterly Journal of Economics 119(4): 1249-1299.

Ganson, B J (1990), “Following their children into battle: Women at war in Paraguay, 1864-1870”, The Americas 46(3): 335-371.

Gay, V (2021), “The legacy of the missing men: The long-run impact of World War I on female labor force participation”, Working Paper.

Jaeggli, A L and F A Bordon (2010), Guerra del Paraguay: Cartografía Explicada de la Guerra Contra la Triple Alianza, Second Edition, Asunción: Servilibro.

Knowles, J and G Vandenbroucke (2019), “Fertility shocks and equilibrium marriage-rate dynamics”, International Economic Review 60(4): 1505-1537.

Pinker, S (2011), The Better Angels of Our Nature: Why Violence Has Declined, New York, NY: Viking.

Potthast, B. (2005), “Progatonists, victims, and heroes: Paraguayan women during the Great War", in H Kraay and T L Whigham (eds), I Die with My Country: Perspectives on the Paraguayan War, 1864-1870, University of Nebraska Press.

Potthast-Jutkeit, B (1991), “The ass of a mare and other scandals: Marriage and extramarital relations in nineteenth-century Paraguay”, Journal of Family History 16(3): 215-239.

Washburn, C A (1871), The History of Paraguay: With Notes of Personal Observations, and Reminiscences of Diplomacy Under Difficulties, Volume 1, Boston: Lee and Shepard.

Whigham, T L and B Potthast (1999), “The Paraguayan Rosetta Stone: New insights into the demographics of the Paraguayan War, 1864-1870”, Latin American Research Review 34(1): 174-186.