Between the start of the financial crisis in 2007 and late 2009, the Eurozone’s periphery countries saw a substantial reduction in economic growth and an increase in deficits. But their economic performance was, if anything, stronger than that in the core countries. The recessions in the periphery were no deeper than in the core, and financial markets absorbed their increasing public debt as they had done in the past, with non-resident creditors absorbing large portions of the increase. By late 2009, average spreads were still low and the share of sovereign debt in the hands of domestic residents was below 50% in all peripheral countries, and even below 30% in Ireland and Greece (Merler and Pisani-Ferry 2012).

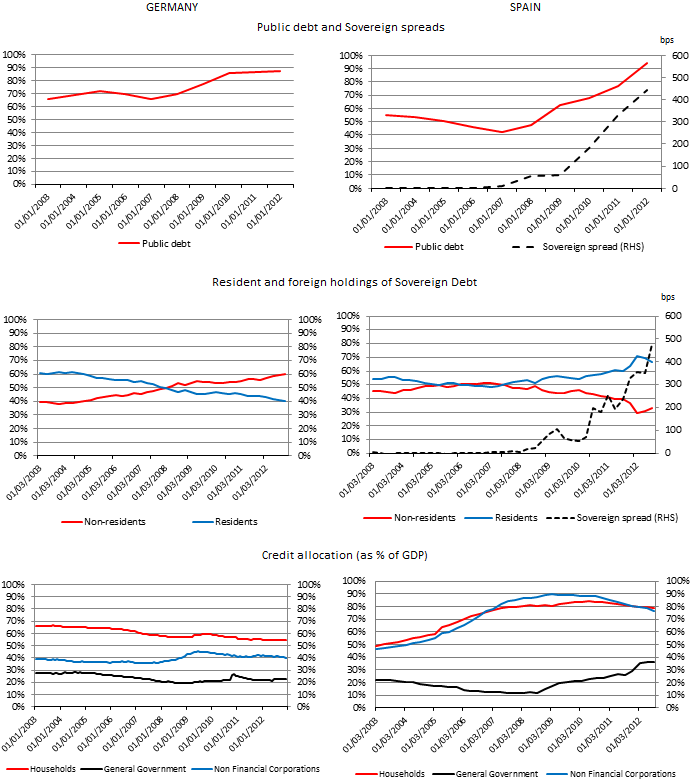

At the end of 2009, as Ireland and Spain reported larger budget deficits than anticipated, and the newly elected Greek government announced that previous deficits were much larger than reported, the situation deteriorated rapidly. Spreads started to rise sharply and the share of debt held by these countries’ private sectors increased (Brutti and Sauré 2013). Thus – and contrary to the logic of optimal diversification – private sectors in the periphery bought a lot of sovereign debt precisely as it became riskier. As domestic banks allocated increasing amounts of funds to the public sector, productive investment declined, further deepening the recessions.. Figure 1 below exemplifies this pattern using data for Spain and Germany.

Figure 1. Macroeconomic developments: Germany and Spain

When difficulties became too large to be handled domestically, help came from abroad in a variety of ways. Greece received loans in May 2010 and March 2012, the former articulated through bilateral agreements with Eurozone countries and an IMF programme, and the latter financed jointly by the IMF and the European Financial Stability Facility. Ireland received a loan in November 2010 and Portugal in April 2011, both jointly financed by the IMF, the European Financial Stabilisation Mechanism and the Stability Facility. As the crisis deepened, the European Stability Mechanism provided financing to clean up the financial systems of Spain in 2012, and Cyprus in 2013.

This provides, in a nutshell, a description of the European crisis since 2007 (for more detailed descriptions of the crisis, see Lane 2012 or Shambaugh 2012). Despite painful fiscal and structural adjustments, the crisis is not over yet. Even worse, there is still widespread disagreement about the underlying causes and potential remedies of this situation. Such an understanding requires a renewed analytical effort.

Creditor discrimination and crowding-out effects

In Broner, Erce, Martin and Ventura (2014), we propose a theory to interpret these events. The theory rests on three key assumptions:

- Governments sometimes discriminate in favour of domestic creditors;

- Public debts trade in secondary markets; and

- Financial frictions limit private borrowing.

In our model, creditor discrimination is introduced as a higher probability of default on foreign than on domestic creditors. As a result, when the probability of default increases, debt becomes relatively more attractive to domestic residents. But discrimination could be broadly interpreted to include a plethora of regulations and moral suasion that increase the incentives of domestic financial institutions to buy their government’s debt in turbulent times. Secondary markets ensure that the debt is allocated to whoever values it most, i.e. domestic and foreign creditors cannot be segmented.

The severity of private financial frictions is crucial to determine the effect of these public debt holdings on investment. At one extreme, if private credit markets worked perfectly, purchases of public debt by domestic creditors could be fully financed through foreign borrowing and would have no effect on investment. Instead, we assume that domestic residents face financial frictions and can only pledge to creditors a fraction of the returns from their public debt holdings or physical investments. As a result, purchases of sovereign debt by domestic creditors displace productive investment. This crowding-out effect creates crucial interactions between default risk, public debt holdings, and investment and growth.

The theory has important implications that resonate well with European events. Consider, for instance, the model’s predictions regarding the effects of a rapid build-up of debt. How does such a build-up affect the domestic economy?

According to the theory, such a build-up has a negative impact on investment and growth when it is accompanied by an increase in sovereign spreads. This is because the increase in spreads induces domestic debt repurchases that displace productive investment and slow down growth. This effect comes about as follows. As spreads on sovereign bonds increase, financially constrained domestic agents have to choose between investing in higher yielding public bonds, which they can acquire from foreign investors in the secondary market, and financing private investment. Insofar as private investment suffers from decreasing returns to scale, an increase in spreads will thus lead to lower investment. This is undesirable because domestic investors are using resources to repurchase public debt precisely when investment is most needed. Indeed, we show that this effect could be so strong as to abort the recovery and permanently trap the economy in a low-output equilibrium. This result seems consistent with the fact that spreads are higher in the European periphery than in the core even though the levels of public debt are similar in both groups of countries.

The relevant question seems to be when will a debt build-up be accompanied by an increase in sovereign spreads? The theory shows that this is likely to occur in economies with weak institutions. Weak institutions can take the form of both strong discrimination against foreigners, and a high tendency for governments to act opportunistically. Moreover, weak institutions open the door to self-fulfilling crises driven by negative shifts in investor sentiment. We show that it is possible to simultaneously have:

- An optimistic equilibrium in which markets expect the probability of default to be low, sovereign spreads remain low, there are no domestic debt repurchases, investment and growth are high, and the probability of default is indeed low; and

- A pessimistic equilibrium in which the market expects the probability of default to be high, sovereign spreads increase, there are domestic debt repurchases, the resulting crowding out leads to low investment and growth, and the probability of default is indeed high.

According to the theory, reducing public debt through fiscal austerity and strengthening institutions can help the economy avoid the risk of such self-fulfilling crises. The theory also shows that an international lender of last resort can be particularly useful in this context.

Finally, the theory also sheds light on the importance of belonging to an economic union. The key assumption we make here is that there is less creditor discrimination against countries inside the union than against countries outside the union. Because of this, demand for public debt from poorer union members is relatively high among richer union members. As a result, crowding-out effects can be ‘exported’ within the union, from poor to rich countries. But any perceived increase in the probability of a union breakup will reduce this effect, leading to sharp reversals in the holdings of debt within the union. Applied to the Eurozone, these results are consistent with both the large build-up of periphery-debt holdings at the core before the crisis and the shift in debt holdings during the crisis. An additional implication of the theory is that union members with strong institutions can intermediate between the international financial market and the union’s distressed members. This intermediation reduces crowding out within the union and can raise growth and welfare in all of its members. Interestingly, the loans made to the periphery by the European Financial Stability Facility and the European Stability Mechanism can be interpreted in this light. By replacing domestic private creditors with foreign creditors, the Facility and the Mechanism can help redirect credit towards productive investment in the periphery while, at the same time, it generates profits that can benefit countries at the core.

Disclaimer: The views expressed in this column are those of the authors, and should not be reported as representing the views of the Bank of Spain or the European Stability Mechanism (ESM).

References

Broner, F, A Erce, A Martin, and J Ventura (2014), “Sovereign debt markets in turbulent times: Creditor discrimination and crowding-out effects”, Journal of Monetary Economics 61, 114-142

Merler, S, and J Pisani-Ferry (2012), “Who's afraid of sovereign bonds?”, Bruegel Policy Contribution 2012/02.

Brutti, F, and P Sauré (2013), “Repatriation of debt in the euro crisis: Evidence for the secondary market theory”, mimeo

Lane, P (2012), “The European sovereign debt crisis”, Journal of Economic Perspectives 26, 49-68.

Shambaugh, J (2012), “The euro's three crises”, Brookings Papers on Economic Activity Spring 2012, 157-211