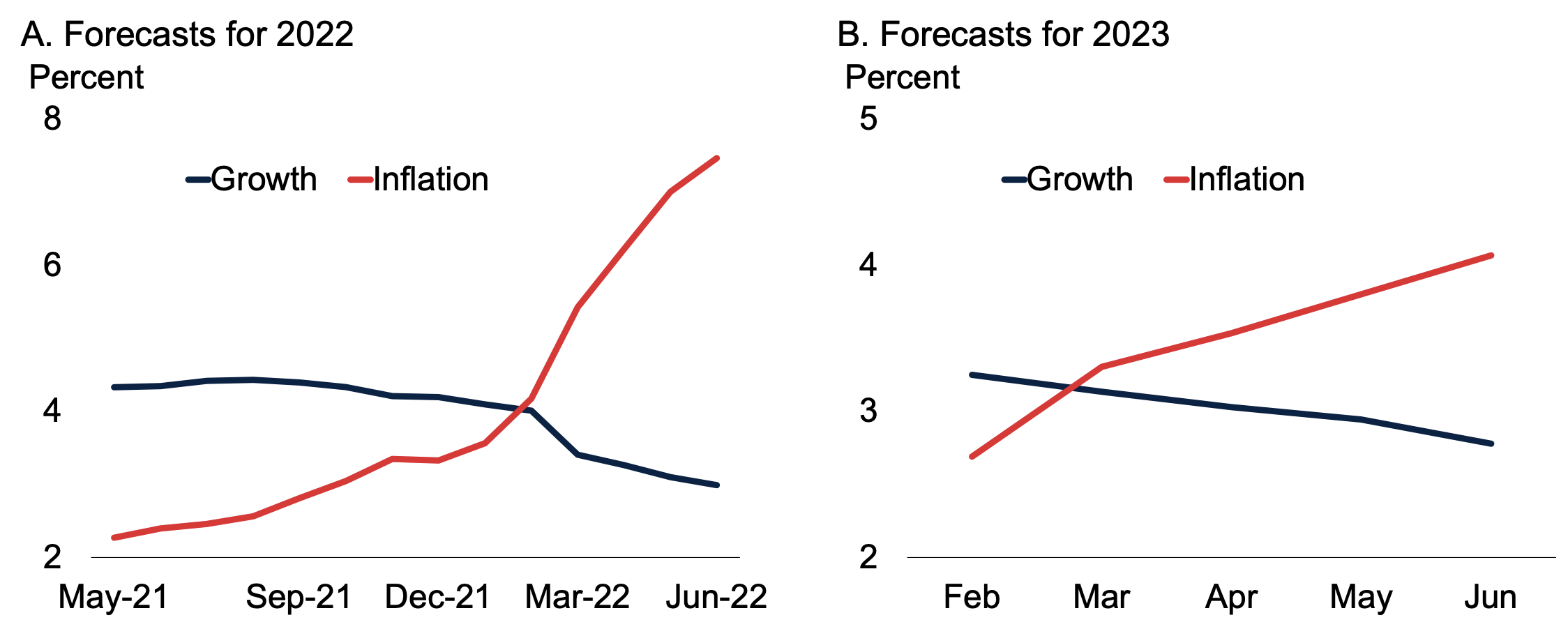

The global economy is in the midst of a steep growth slowdown accompanied by multi-decade high inflation. Global inflation forecasts for 2022-23 have been sharply upgraded, while global growth forecasts have been downgraded over the past year (Figure 1). This combination of high inflation and weak growth has raised concerns about a potentially prolonged period of stagflation that resembles the 1970s (DeLong 2022, Verwey et al. 2022). Some argue that central banks need to sharply increase policy interest rates to get ahead of inflation (Buiter and Sibert 2022, Domash and Summers 2022).

This historical precedent also raises worries about the risk of debt crises in emerging market and developing economies (EMDEs), reminiscent of the early 1980s when massive increases in policy interest rates were needed to tame inflation.

Figure 1 Global growth and inflation forecasts

Sources: Consensus Economics; World Bank.

Note: Growth forecasts for aggregate groups are weighted by GDP in US dollars based on 86 countries, and inflation forecasts are based on median based on 83 countries. The last observation is June 2022.

Another traumatic tightening cycle on the horizon?

By some measures, today’s inflation is comparable to that in the early 1980s (Bolhuis et al. 2022). Looking ahead, global inflation is expected to peak this year and decline to about 3% in mid-2023 as global growth slows, monetary policy tightens, fiscal support is withdrawn, commodity prices level off, and supply bottlenecks ease. This would still be about one percentage point above its average in 2019. For now, consensus forecasts suggest that inflation expectations remain well-anchored over the medium term, even if a pickup in inflation is expected in the short term.

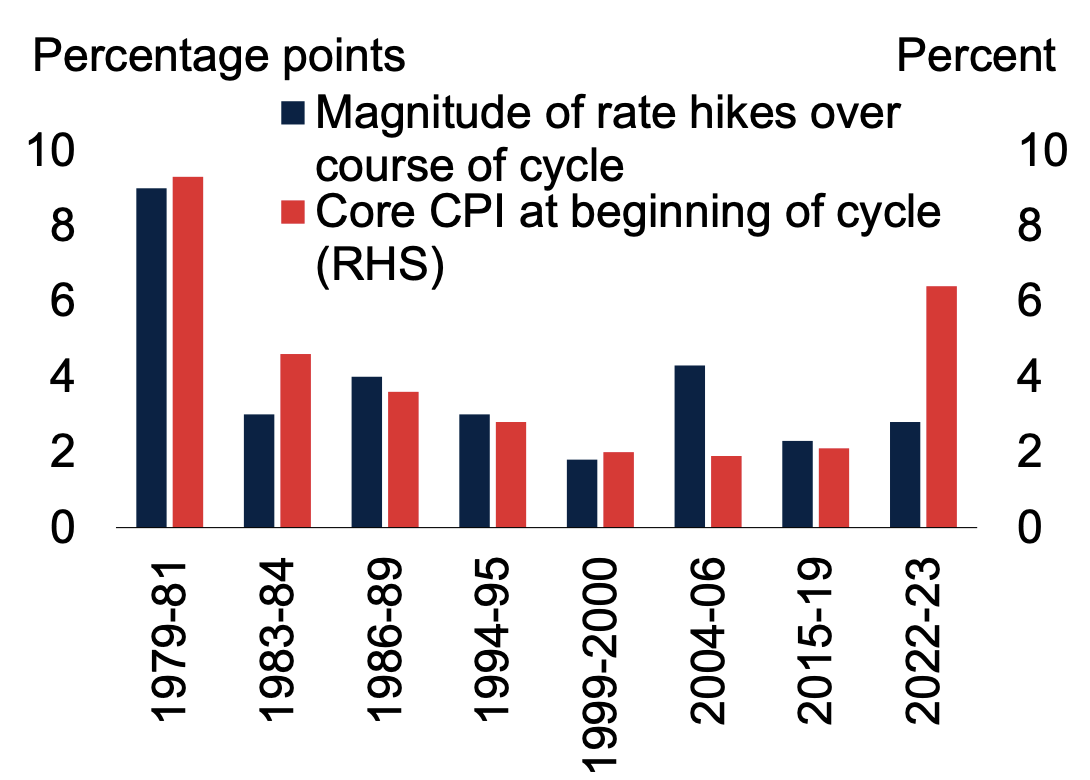

However, there is a risk that inflation expectations will eventually de-anchor, as they did in the 1970s, as a result of persistently above-target inflation and repeated inflationary shocks. Concerns about persistently above-target inflation have already prompted central banks in most advanced economies and many EMDEs to tighten monetary policy. Financial markets now expect a 200–400 basis point increase in monetary policy rates by the US Federal Reserve, the ECB, and the Bank of England over the course of 2022-23 to be needed to return inflation into target ranges in these countries. Such a tightening cycle would be moderate by historical standards (Figure 2).

Figure 2 Interest rates and inflation during US tightening cycles

Sources: Federal Reserve Economic Data; Havers Analytics; World Bank.

Note: Blue bars show the extent of cumulative US policy rate increases during previous Federal Reserve tightening cycles: 1979-81, 1983-84, 1986-89, 1994-95, 1999-2000, 2004-06, 2015-19. Value for 2023 is an estimate based on market expectations for the level of the Fed Funds rate in mid-2023. Red bars show core CPI inflation rates, the latest data for 2022-23.

If inflation expectations come adrift, the interest rate increases required to bring inflation back to target could be much greater than those currently anticipated by financial markets. For comparison, in the 1970s, it took a doubling of global interest rates to 14% over six years (1975-1981). In 1979-1981 alone, US policy rates rose by nine percentage points to 19%. These synchronous policy rate hikes around the world did bring the Great Inflation to an end. However, they also triggered a global recession in 1982 and sparked a series of debt crises in EMDEs in the 1980s (Ha et al. 2022a, 2022b).

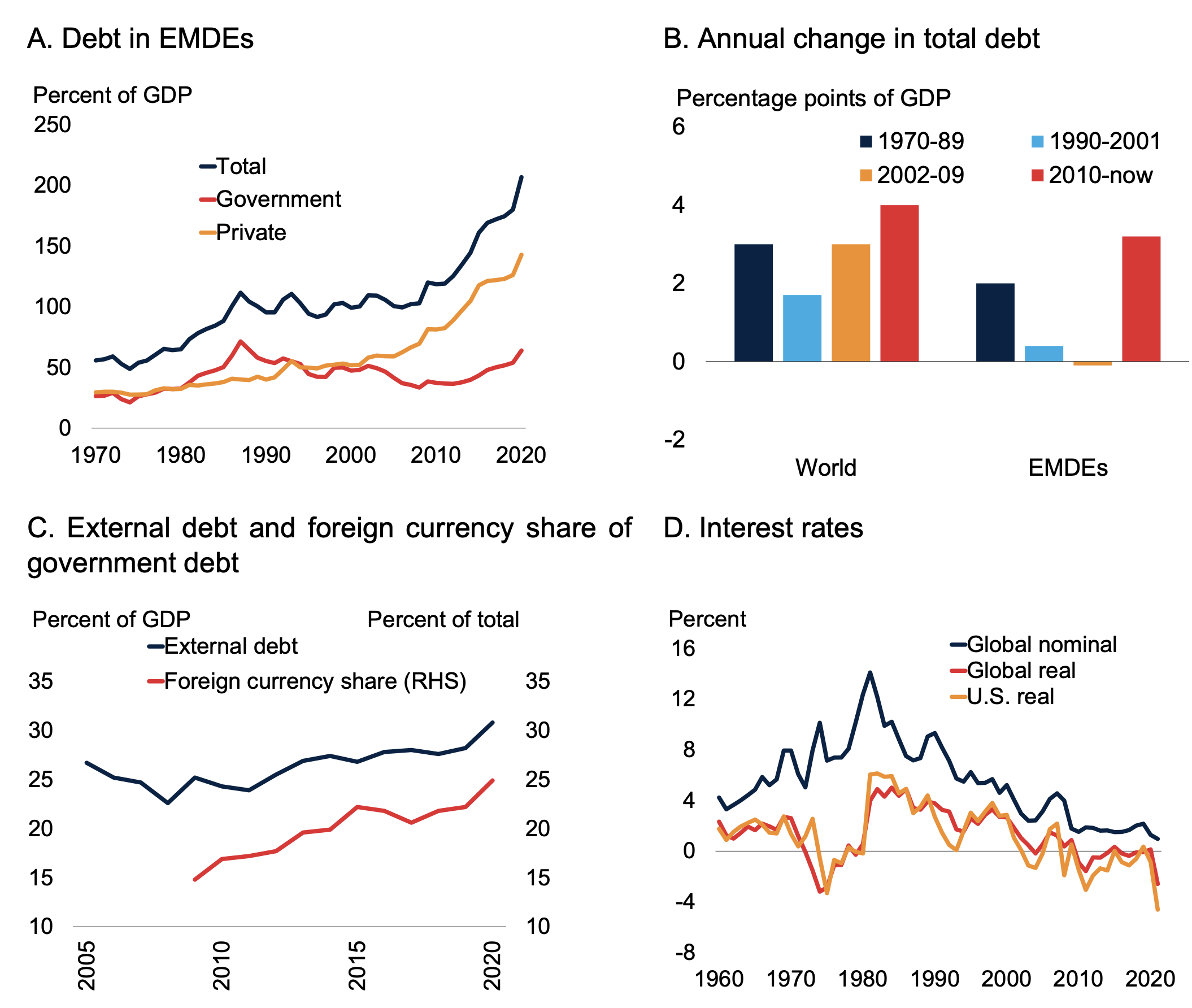

Large debt accumulation: Then and now

In the 1970s and early 1980s, as now, high debt, elevated inflation, and weak fiscal positions made EMDEs vulnerable to tightening financial conditions. The stagflation of the 1970s coincided with the first global wave of debt accumulation in the past half-century (Figure 3, Kose et al. 2020). Low global real interest rates and the rapid development of syndicated loan markets encouraged a surge in EMDE debt, especially in Latin America and many low-income countries, especially in sub-Saharan Africa.

Figure 3 Debt and interest rates

Sources: Federal Reserve Economic Data; Haver Analytics; International Monetary Fund; Kose et al. (2020); World Bank.

Notes: A. GDP-weighted averages based on a sample of up to 153 EMDEs. Four waves of broad-based debt buildup in EMDEs since 1970 include the following: 1970-89; 1990-2001; 2002-09; 2010 onwards; B. Figure shows the average annual change in total debt. Rate of change is calculated as the total increase in debt-to-GDP ratios over the duration of a wave, divided by the number of years in a wave; C. External debt (per cent of GDP) is based on a GDP-weighted average of up to 137 EMDEs. The foreign currency share of government debt is an average of up to 36 EMDEs; D. Figure shows nominal and real (CPI-adjusted) short-term interest rates (Treasury bill rates or money market rates, with the maturity of three months or less). Global interest rates are weighted by GDP in US dollars. The sample includes 113 countries, although the sample size varies by year.

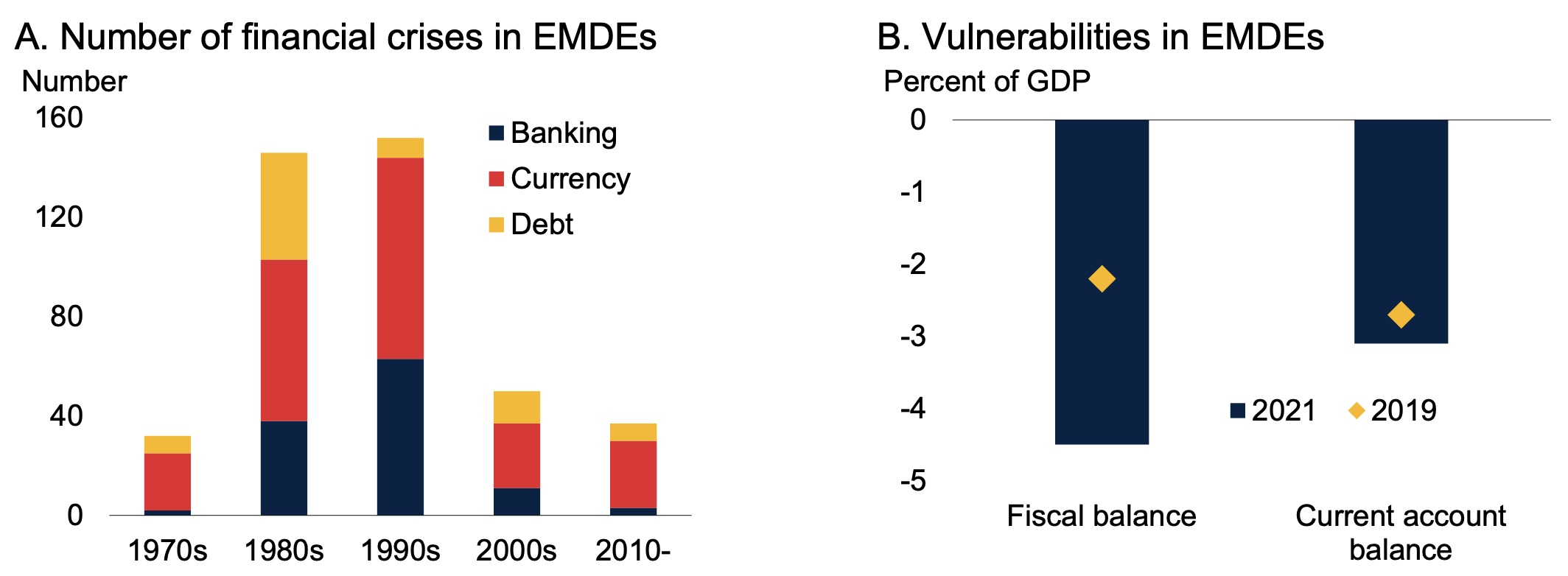

Monetary policy tightening in advanced economies sharply increased the cost of borrowing, especially in Latin America and the Caribbean (LAC), where variable-rate debt accounted for more than half of total debt in 1982. Interest payments on external debt by LAC countries rose sharply, from an average of 1.6% of GDP in 1975-79 to 5% of GDP by 1982. A steep growth slowdown weakened debt servicing capacity further. Over the 1980s, more than three dozen debt crises erupted, mostly in LAC and sub-Saharan Africa (Figure 4).

Figure 4 Financial crises and vulnerabilities in EMDEs

Sources: Kose et al. (2020); Haver Analytics; International Monetary Fund; Laeven and Valencia (2020); World Bank.

Notes: A. Total number of banking, currency, and sovereign debt crises in EMDEs over respective periods; B. Medians based on a sample of up to 155 EMDEs.

Should steep policy rate hikes now again be required to bring inflation in advanced economies under control, EMDEs would once again face severe challenges. Total EMDE debt is at a record high of 207% of GDP. EMDE government debt, at 64% of GDP, is at its highest level in three decades, and about one-half of it is denominated in foreign currency, and more than two-fifths are held by non-residents in the median EMDE (Kose et al. 2022). A sharp increase in borrowing cost – or the sharp currency depreciation that often accompanies policy tightening in advanced economies – could once again trigger sovereign debt distress as these economies have even larger vulnerabilities now than before the pandemic. About 60% of the poorest countries are already in, or at high risk of, debt distress.

Getting ready

If inflation remains above target for a prolonged period, there is a risk that inflation expectations come adrift. Much larger policy rate hikes in advanced economies would then be required to achieve the same inflation target. Coupled with high debt and sizeable fiscal and current account deficits of many EMDEs, there is a danger that financial stress will emerge in these economies amid a steep global growth slowdown. These risks are particularly acute among those EMDEs with large current account deficits and a heavy reliance on foreign capital inflows, as well as those with high levels of short-term or foreign currency-denominated government or private debt. These economies need to get ready to weather the storm associated with the tightening cycle. This starts with a careful calibration, credible formulation, and clear communication of their policies.

References

Bolhuis, M A, J N L Cramer and L H Summers (2022), “Past and Present Inflation Are More Similar Than You Think,” VoxEU.org, June 22.

Buiter, W and A Sibert (2022), “Central Banks Are Still Far Behind the Inflation Curve,” Project Syndicate, June 9.

DeLong, J B (2022), “Why the US Federal Reserve’s Options Are Limited,” Project Syndicate, June 14.

Domash, A and L H Summers (2022), “Overheating Conditions Indicate High Probability of a US Recession,” VoxEU.org, April 22.

Ha, J, M A Kose and F Ohnsorge (2022a), “Global Stagflation”, CEPR Discussion Paper 17381.

Ha, J, M A Kose and F Ohnsorge (2022b), “Today’s inflation and the Great Inflation of the 1970s: Similarities and differences”, VoxEU.org, April 30.

Kose, M A, F Ohnsorge and N Sugawara (2022), “A Mountain of Debt: Navigating the Legacy of the Pandemic,” World Bank Policy Research Working Paper No. 9800.

Kose, M A, P Nagle, F Ohnsorge and N Sugawara (2020), Global Waves of Debt, Washington, DC: World Bank.

Kose, M A, N Sugawara and M Terrones (2020), “Global Recessions”, World Bank Policy Research Working Paper 9172.

Laeven, L and F Valencia (2020), “Systemic Banking Crises Database II”, IMF Economic Review 68(2): 307-361.

Verwey, M, L Bardone and K Orsini (2022), “Russian Invasion Tests EU Economic Resilience,” VoxEU.org, May 20.