The development and adoption of artificial intelligence (AI) is rapidly and profoundly reshaping economies and societies worldwide. AI systems have the potential to impact all industries and occupations that rely on data and information, from healthcare diagnostic to drug discovery, from fraud detection to quality control, from self-driving cars to language translation, from crop disease detection to the design of smart grids. Although AI presents significant opportunities for innovation (Agrawal et al. 2018), productivity (Calvino and Fontanelli 2023, Noy and Zahng 2023), and wellbeing (Pissarides and Bughin 2019, Yamamoto 2019), it also poses risks – for example, for inequality, financial markets, and democratic values (Danielsson 2017, Pastorello et al. 2019; Acemoglu 2021) – that are at the centre of recent economic and policy discussions (e.g. Gans et al. 2018, Bholat 2020).

As organisations race to harness the potential of AI, companies worldwide seek professionals with the skills needed to develop, design, maintain, and implement AI solutions to optimise production processes, enhance customer experiences, and drive innovation. In this context, in a recent paper (Borgonovi et al. 2023) we explore changes in the demand for professionals with such skills, based on recent and comprehensive information sourced from online job postings across countries. Our paper builds upon and significantly extends previous work based on skills demand in English-speaking countries (e.g. Restrepo et al. 2021 or Taska 2020 for evidence on the US) and complements analyses on the role of AI for labour markets (e.g. Albanesi et al. 2023 OECD 2023).

The number of online vacancies requiring prospective employees to possess AI-related skills grew markedly between 2019 and 2022…

By leveraging comprehensive information from online job postings (see our paper for the full analysis and more details on the methodology), we estimated, for the first time, changes in the demand for professionals with skills needed to develop, maintain, and adopt AI between 2019 and 2022 in 14 OECD countries.

Together, these countries account for 46% of GDP during that period.

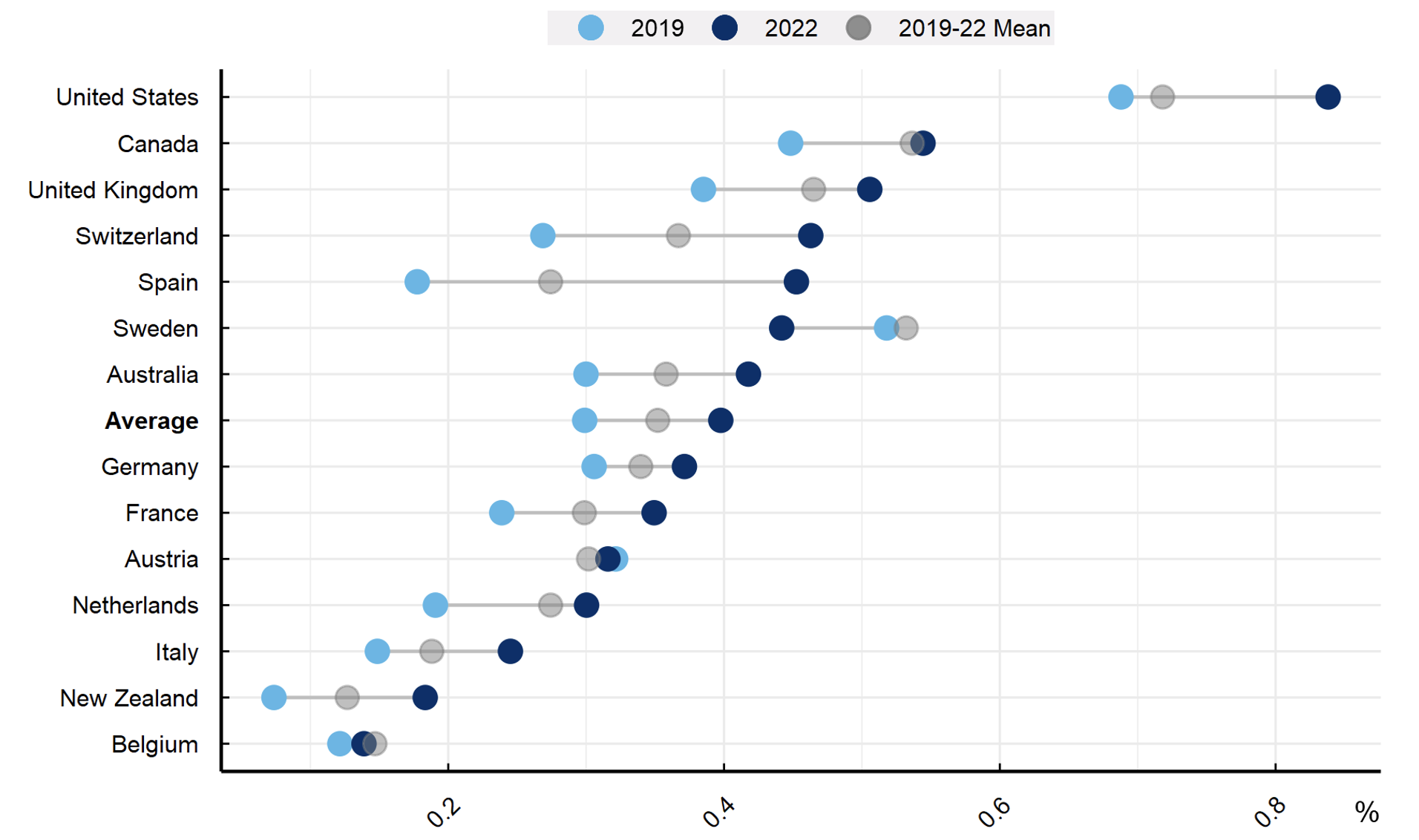

On average across the 14 countries analysed, the share of online vacancies requiring AI skills increased by 33% during the period, but this average masks large differences across countries (see Figure 1). For example, in Spain and New Zealand, two countries with a low share of online vacancies requiring AI-related skills in 2019, the share increased by as much as 155% and 150%, respectively, by 2022. By contrast, in countries with relatively high shares of online vacancies requiring AI skills in 2019, such as the US, the increase over time was more modest – at around 22%. And in Sweden and Austria, there was no change between 2019 and 2022.

…but only a few occupations require the specialised skillset needed to develop, adapt, and modify AI systems

Despite a rapid growth in the demand for professionals with AI skills, only a few occupations require the specialised skillset necessary to develop, adapt, and modify AI systems. For example, in 2022 the share of online vacancies requiring AI-related skills was highest in the US, but represented only 0.84% of all job postings. In Canada and the UK, such vacancies represented even less of total job postings (around 0.5%), while in New Zealand and Belgium they represented less than 0.2%. In fact, the share of all online vacancies requiring AI skills did not exceed 1% of all vacancies being posted online in any country or year analysed.

Figure 1 Trend in the share of online vacancies requiring AI skills by country, 2019-22

Percentage of online vacancies advertising positions requiring AI skills, by country

Note: The figure shows the percentage of AI online vacancies by country, which is the total number of online vacancies requiring AI skills relative to all vacancies advertised in a country. Vacancies requiring AI skills are vacancies in which at least two generic AI skills or at least one AI-specific skill were required (see Section 2.2 in Borgonovi et al. (2023) on generic and specific skills). Countries are sorted in descending order by the highest average share of vacancies requiring AI skills in 2022.

Source: Borgonovi et al. (2023)

Skills related to machine learning are most demanded across countries…

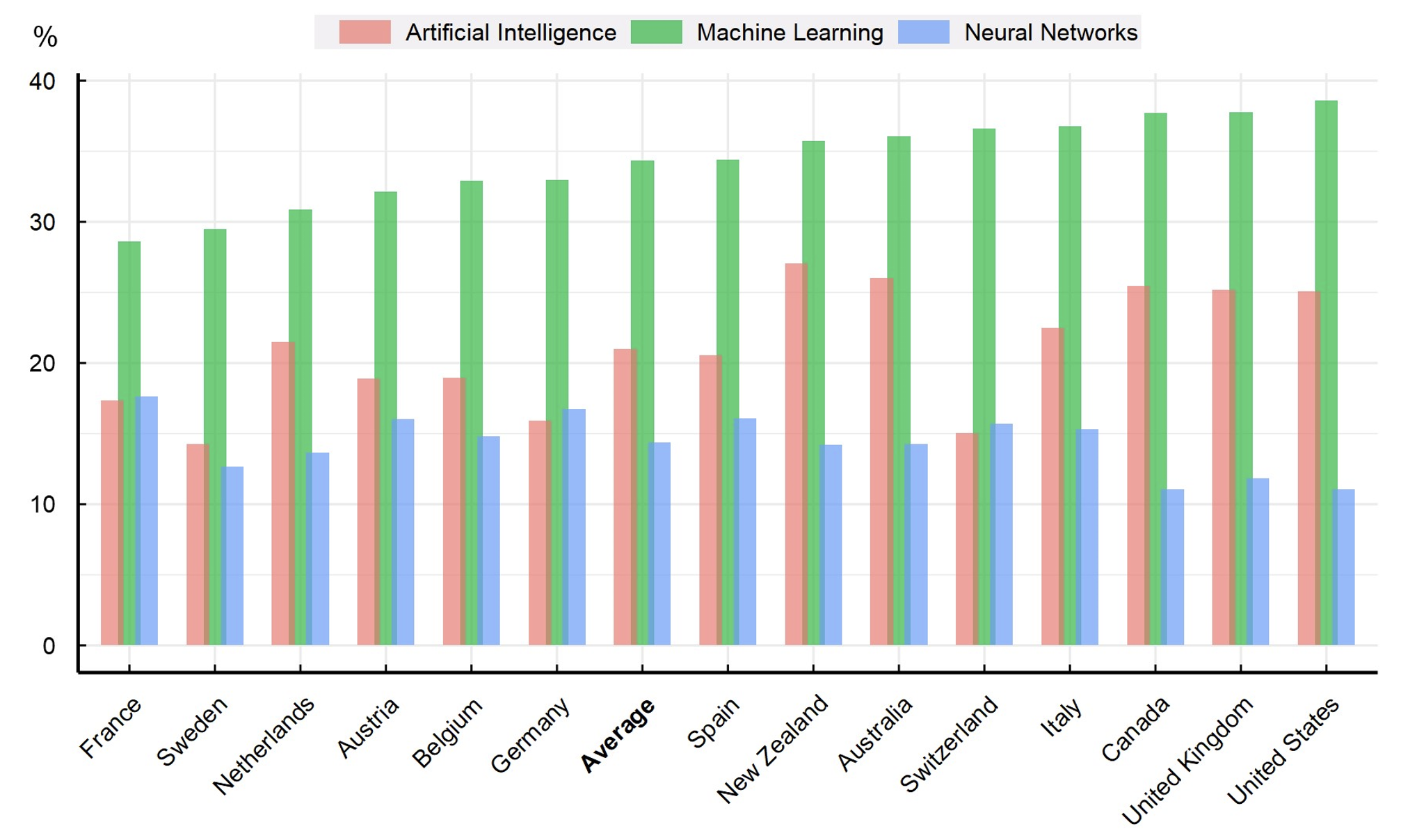

In most countries, out of all AI-related skills, skills related to “machine learning”, “artificial intelligence”, and “neural networks” were most in demand. For instance, as is evident from Figure 2, on average, 34% of online vacancies requiring AI skills required skills related to machine learning, 21% required skills related to AI, and 14% required skills related to neural networks. Furthermore, although across countries only around 5% of online vacancies required skills related to “autonomous driving”, in France and Sweden as many as 19% and 17% of vacancies did.

…yet the skill set required for AI professionals goes well beyond technical expertise. ‘Soft skills’ are also in high demand.

While a strong foundation in technical skills such as programming, statistics, and mathematics, as well as AI-specific skills, is essential, non-technical skills are also in high demand among companies hiring AI professionals. For example, in the US around 20% of the skills mentioned in vacancies for AI professionals refer to socio-emotional and foundational skills. While communication skills are very common in postings across the board, more AI-related online vacancies (compared to non-AI postings) demand leadership and management skills, as well as innovation, research, problem-Solving and mentorship, reflecting the need for AI workers to be endowed with a broad skill mix, including technical as well as socio-emotional skills.

Figure 2 Top three skills clusters demanded in postings requiring AI skills, 2019-22

Percentage of online vacancies requiring AI skills averaged across 2019-22, by skill cluster and country

Note: The figure shows the percentage of AI online vacancies for specific skill clusters, for the top three skill clusters, by country, which is the total number of online vacancies requiring a specific skill cluster relative to the total number of AI vacancies (see Annex Table C.1 in Borgonovi et al. (2023) which AI skills are assigned to which cluster). Countries are sorted in descending order by percentage of vacancies requiring “Machine Learning” skills. “Artificial intelligence” is a broad term used to characterise a group of skills, such as artificial intelligence development, artificial general intelligence, artificial intelligence systems, cognitive computing, expert systems, etc. Average refers to the average across 2019-22 and 14 countries with available data.

Source: Borgonovi et al. (2023)

Given its transformational nature, AI has been met with polarised attitudes among adults in OECD countries. It is the subject of intense scrutiny over whether it will substitute or complement workers, give rise to better or worse labour market conditions, and ultimately whether it will deliver better or worse labour market opportunities. Although few individuals work on the development of AI systems, these professionals are critical agents of change for economic and social systems.

Emphasising both technical expertise and soft skills in education and training programmes will be key to meeting the demands of this dynamic field. Moreover, as AI continues to transform businesses and societies, and especially as generative AI technologies emerge, the skills required for AI professionals will continue to evolve. Mapping the demand for professionals engaged in AI development and adaptation will be critical for understanding the evolving landscape of technology-driven industries and how best to ensure an adequate skills pipeline.

Authors’ note: The views expressed here are those of the authors and cannot be attributed to the OECD or its member countries.

References

Acemoglu, D (2021), “Dangers of unregulated artificial intelligence”, VoxEU.org, 23 November.

Agrawal, A, J McHale, and A Oettl (2018), “Finding Needles in Haystacks: Artificial Intelligence and Recombinant Growth”, in The Economics of Artificial Intelligence: An Agenda, NBER Chapters, pp. 149–174.

Albanesi, S, Dias da Silva, A, Jimeno, J F, Lamo, A, and A Wabitsch (2023), “Artificial intelligence and jobs: Evidence from Europe”, VoxEU.org, 29 July.

Bholat, D (2020), “The impact of machine learning and AI on the UK economy”, VoxEU.org, 2 July.

Borgonovi, F, F Calvino, C Criscuolo, J Nania, J Nitschke, L O’Kane, L Samek and H Seitz (2023), "Emerging trends in AI skill demand across 14 OECD countries", OECD Artificial Intelligence Papers, No. 2.

Calvino, F and L Fontanelli (2023), “Firms’ use of artificial intelligence: Cross-country evidence on business characteristics, asset complementarities, and productivity”, VoxEU.org, 14 June.

Danielsson, J (2017), “Artificial intelligence and the stability of markets”, VoxEU.org, 15 November.

Gans, J, Goldfarb, A and A Agrawal (2018), “Economic policy for artificial intelligence”, VoxEU.org,8 August.

Noy, S and W Zhang (2023), “The productivity effects of generative artificial intelligence”, VoxEU.org, 7 June.

OECD (2023), OECD Employment Outlook 2023: Artificial Intelligence and the Labour Market, OECD Publishing, Paris.

Pastorello, S, G Calzolari, V Denicolo and E Calvano (2019), “Artificial intelligence, algorithmic pricing, and collusion”, VoxEU.org, 3 February.

Pissarides, C and J R J Bughin (2019), “Measuring the welfare effects of AI and automation”, VoxEU.org, 28 May.

Restrepo, P, D Autor, J Hazell and D Acemoğlu (2021), “AI and jobs: Evidence from US vacancies”, VoxEU.org, 3 March.

Taska, B, S Samila, J Azar, M Gine, and L Alekseeva (2020), “The demand for AI skills in the labour market”, VoxEU.org, 3 May.

Yamamoto, I (2019), “The impact of AI and information technologies on worker stress”, VoxEU.org, 14 March.