Democratic countries such as Germany, Israel, the UK, and the US were among the few first to start COVID-19 vaccination campaigns. However, after some initial success, these campaigns soon faced a persistent vaccine hesitance among large parts of the population (Dewatripont 2021). As of November 2021, 46 nations, including Brazil, China, and other emerging countries, have surpassed the US in vaccination uptake rates (Holder 2021). On 13 January 2022, only about 62% of the US population had been fully vaccinated, as well as 71% in Germany, 70% in the UK, and 64% in Israel (Our World in Data 2022, Mathieu et al. 2021).

Recently, mandates for the COVID-19 vaccine have been implemented in Germany and the US to forcefully deal with vaccine hesitancy (Reuters 2021). Many European countries are currently preparing or starting compulsory vaccination at various levels (Burki 2022). Given the many advantages that these countries possess, the current situation raises a lot of questions, including: What explains vaccine resistance? What are common factors of success across countries?

Previous research has mainly focused on behavioural sciences to boost vaccine uptake rates (Schubert 2016). Research from Japan shows that information about vaccinations may inspire others: older persons got vaccinated if they were getting it for free, but younger adults did not seem to be affected by ‘nudges’ (Sasaki et al. 2021). In the US, Chang et al. (2021) found that neither financial incentives nor public health messaging or a simple vaccination appointment planner could raise the uptake rates in the vaccine-hesitant population. Improving take-up will need stronger regulatory levers, ranging from workplace norms to government mandates. In contrast, Campos-Mercade et al. (2021) found that even a mediocre monetary incentive of €20 significantly enhanced vaccination rates.

Given the inconsistent findings in behavioural studies, we use data from 118 countries to provide global evidence on the fundamental factors that improved or hindered vaccination uptake and speed (Ngo et al. 2021).

Data and methodology

While it is much too early to judge the entire vaccination process, which is still ongoing, the rollout after the various vaccines became available and the initial speed can be examined. In our paper (Ngo et al. 2021), we therefore assess the performance of initial COVID-19 immunisation campaigns until October 2021 by counting the days it took each country to reach specified vaccinated population shares (1%, 5%, 10%, 20%, and 30%), as the total number of doses over the total population.

Political, educational, and economic background variables are considered key predetermined driving forces. We employ a democracy index (‘political regimes’) suggested by the 2020 Economist democracy report (Economist Intelligence Unit 2020), which classifies countries into full democracy, flawed democracy, hybrid, and authoritarian regimes based on their democratic score (1 to 10). The expected years of schooling index (UNDP 2020) captures the state of the educational system (‘education’). Further, GDP per capita measures economic strength. We include control variables like continent dummies, population density, population shares of people 65 and older, and vaccine purchases. Average COVID-19 new cases (from January 2020 to 11 October 2021) were used to capture societal pressures. The estimation method was weighted least squares using population size as weights with robust standard errors. We also calculated Owen-Shapley R2-decompositions to judge the contributions of the key variables to the explained variance and hence reveal their relevance.

Our study shows that it took nations around 36 days to attain a 1% vaccination level. The average number of days it took to cross 5%, 10%, 20%, and 30% was about 73, 93, 116, and 134 days, respectively. Higher vaccination rates were achieved faster thereafter.

The sample’s average GDP per capita is US $22,700. However, for the economically diverse 118 nations, economic strength varies greatly, between US $920 and US $116,900. Similarly, education (expressed in projected school years) shows a wide range of 6.4 to 21.9 years, with an average of 14.1 years.

Decomposing the COVID-19 vaccination campaigns

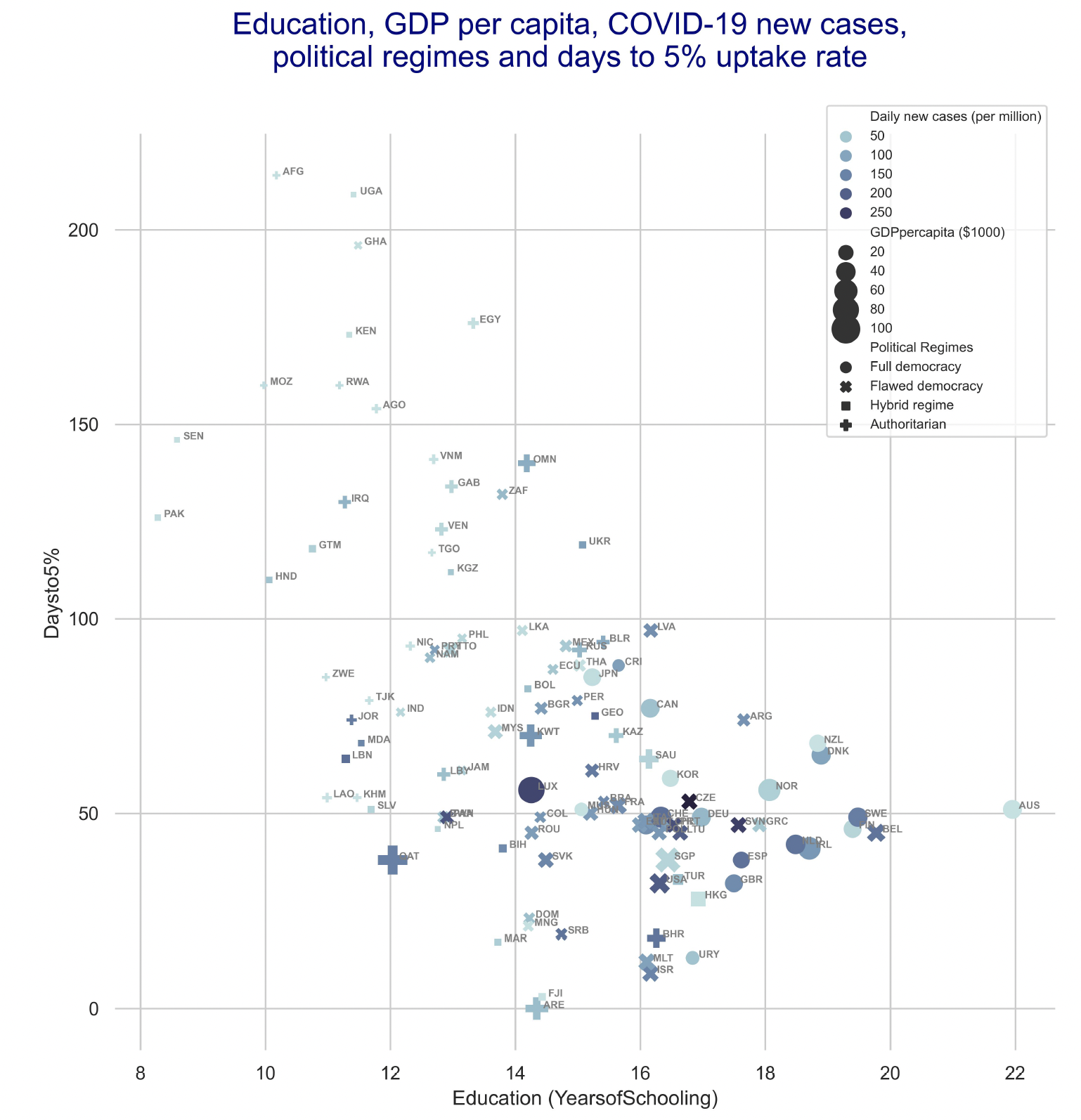

Figure 1 depicts the relationships among education, GDP per capita, infected new cases, political regimes, and the number of days needed to achieve 5% and 30% uptake rates. The colour (light blue to dark blue) represents average new cases, the size of the dot reflects GDP per capita, and the markers reveal the political regimes of the countries.

Figure 1 Education, GDP per capita, new cases, political regimes and number of days needed to achieve vaccination uptake rates.

Notes: The colour (light blue to dark blue) represents average new cases, the size of the dot reflects GDP per capita, and the markers reveal the political regimes of the countries.

These two diagrams show the complex vaccination rollout structure, which is more clearly confirmed by our econometric investigation. For both 5% and 30%, the downward sloping cloud of points suggests that education is a strong and persistent factor associated with fast vaccination success. The size of the dots is larger in the lower parts of both diagrams indicating that higher GDP per capita is also associated with faster vaccinations. Not surprisingly, the colour of those countries clustering in the upper parts of both diagrams is light; in general, low levels of infections (new cases) reduce the pressure on vaccination rollout speed.

The 5% panel (Figure 1, top) contains two clusters of countries separated by a line at 100 days. The cluster in the upper left (above 100 days) contains countries with low education, low GDP per capita, few new cases but dominant autocratic or hybrid political regimes. The cluster below 100 days (countries reaching the 5% goal faster) and to the right shows higher education, higher GDP per capita, more new cases but a mixed collection of political regimes, with both more democratic and more authoritarian settings. The importance of political regimes fades out for the 30% uptake rate (Figure 1, bottom panel).

The main results of our regression analysis exploring the role of a larger number of determinants based on Ngo et al. (2021) are visualised in Figures 2 and 3. The symbols represent the parameter estimates and the dashed lines the 95% confidence interval revealing statistical significance. The more negative the parameters are, the faster the vaccination goal is reached; the broader the dashed line is, the lower is the statistical significance. Figure 2 shows that the number of days it took to achieve the different vaccination uptake rates is negatively associated with democratic features, using authoritarian countries as the reference. More democratic countries had faster vaccination campaigns. While the estimated parameters for the three categories of democracy (full, flawed and hybrid) are negative, their significance and magnitudes vary at different uptake rates. They are significant at the 1%, 5%, and 10% levels. The type of democracy accounts for 14.2% of the overall explained variance in the days it took to reach the 1% vaccination level. This finding was quite stable throughout the campaigns, and 14.8% of the measured total explained variance of vaccinations (73%) to reach or pass the 30% threshold is associated with political regime variables.

Figure 2 Impacts of political regimes (authoritarian as reference group) on speed of vaccination campaign, in days

Note: 95% confidence intervals given.

Figure 3 illustrates the strength of education, GDP per capita, and new cases with the various vaccination levels. Educated nations showed a negative and statistically significant influence on the time required to reach certain levels of vaccination. Education accounts for 24.1% of the explained variance in the number of days it took to reach the1% vaccination level; it accounts for somewhat less but still significant amounts of variance in the subsequent vaccination stages (19.1%, 15.1%, 18.7%, and 17.8%). Education is always more important than political regimes for expediting vaccination uptake.

The impact of GDP per capita became larger (and hence vaccination faster) and very significant for higher vaccination thresholds. The Owen-Shapley decomposition assigns the largest contributions of 17.7% on days to reach 10% vaccination levels, 34.5% to reach 20% vaccination, and 34.7% to reach 30% vaccination. GDP per capita also contributes the most to vaccination speed among all variables, including political regimes.

Figure 3 Impacts of education, economic strength, infection intensity on speed of vaccination campaign (days)

Note: 95% confidence intervals given.

The strength of the epidemic, measured by new cases, encouraged governments to ramp up their immunisation efforts. According to the Owen-Shapley contributions, this pressure is greatest in reaching 1% and 5% vaccination rates, accounting for 19.2% and 14.8% of the total explained variance. Differences in vaccine policies mattered initially, but not afterwards. In contrast to North and Middle America, European and Asian nations reached the 5% and 10% vaccination levels more rapidly, but their pace slowed considerably after reaching 30% vaccination levels and beyond.

Discussion

There are large regional differences in how the pandemic presents itself and how populations and political authorities respond to it. Vaccinations are thought to be the silver bullet to contain COVID-19. While this simple view daily loses ground due to the immense adaptability of the virus, it is important to understand the basic mechanisms of fast vaccination uptake. Education and economic strength are shown to be global factors for success; the type of political regime is not as relevant. This sends an important message for policymaking: since the challenge is global, the rich and educated countries of the world need to support those that are still behind. It is also in their own interest.

References

Burki, T (2022), “COVID-19 vaccine mandates in Europe”, The Lancet: Infectious Diseases 22(1): 27–28.

Campos-Mercade, P, A Meier, F Schneider, S Meier, D Pope and E Wengström (2021), “Monetary incentives increase COVID-19 vaccinations, nudges do not”, VoxEU.org, 19 November.

Chang, T, M Jacobson, M Shah, R Pramanik, and S B Shah (2021), “Financial incentives and other nudges do not increase COVID-19 vaccinations among the hesitant”, VoxEU.org, 8 December.

Dewatripont, M (2021), “Covid vaccination experiences”, VoxEU.org, 1 October.

Holder, J (2021), “Tracking coronavirus vaccinations around the world”, New York Times, 19 November.

Mathieu, E, H Ritchie, E Ortiz-Ospina, et al. (2021), “A global database of COVID-19 vaccinations”, Nature Human Behaviour 5: 947–53.

Ngo, V M, K F Zimmermann, P V Nguyen, T L D Huynh and H H Nguyen (2021), “How education and GDP drive the COVID-19 vaccination campaign”, CEPR Discussion Paper 16757.

Our World in Data (2022), “COVID vaccination data”, retrived on 14 January 2022.

Reuters (2021), “Germany mandates vaccines for health care workers”, 10 December.

Sasaki, S, T Saito and F Ohtake (2021), “How to nudge COVID-19 vaccination while respecting autonomous decision making”, VoxEU.org, 13 December.

Schubert, C (2016), “A note on the ethics of nudges”, VoxEU.org, 22 January.

Economist Intelligence Unit (2020), Democracy index 2020.

UNDP (2020), “Human development index (HDI)”, Human Development Reports.