A monetary shock of the past can shed light on the large foreign reserves held by China today. In the 1500s, European explorers found a new continent and a ‘mountain’, or several mountains, of gold and silver in Peru (modern Bolivia), Mexico, and later in Brazil. It was a huge discovery, with more impact than finding the same treasure today. Gold and silver were used as monetary standards. Finding precious metals was equivalent to having a monetary authority increase money supply. Argentina owes its name to the fact that it offered the safest access to the mines (through River Plate, the ‘river of silver’).

Add to this discovery of precious metals a region of the world – Asia – with difficulties in establishing a monetary system (von Glahn 1996, de Vries 2003), eager to import precious metals, and a decrease in trading costs obtained with the opening of new routes from Europe to Asia around Africa and across the Pacific. Then you have the perfect storm for the use of precious metals for intensive international trade.

As a result, Europe imported many times more goods from Asia than without the precious metals. There was a large trade deficit of Europe with Asia. Imports of Asian goods were not offset by the exports of European goods; they were offset by exports of precious metals. Asia imported most of the production of precious metals from America. China accumulated large reserves of silver.

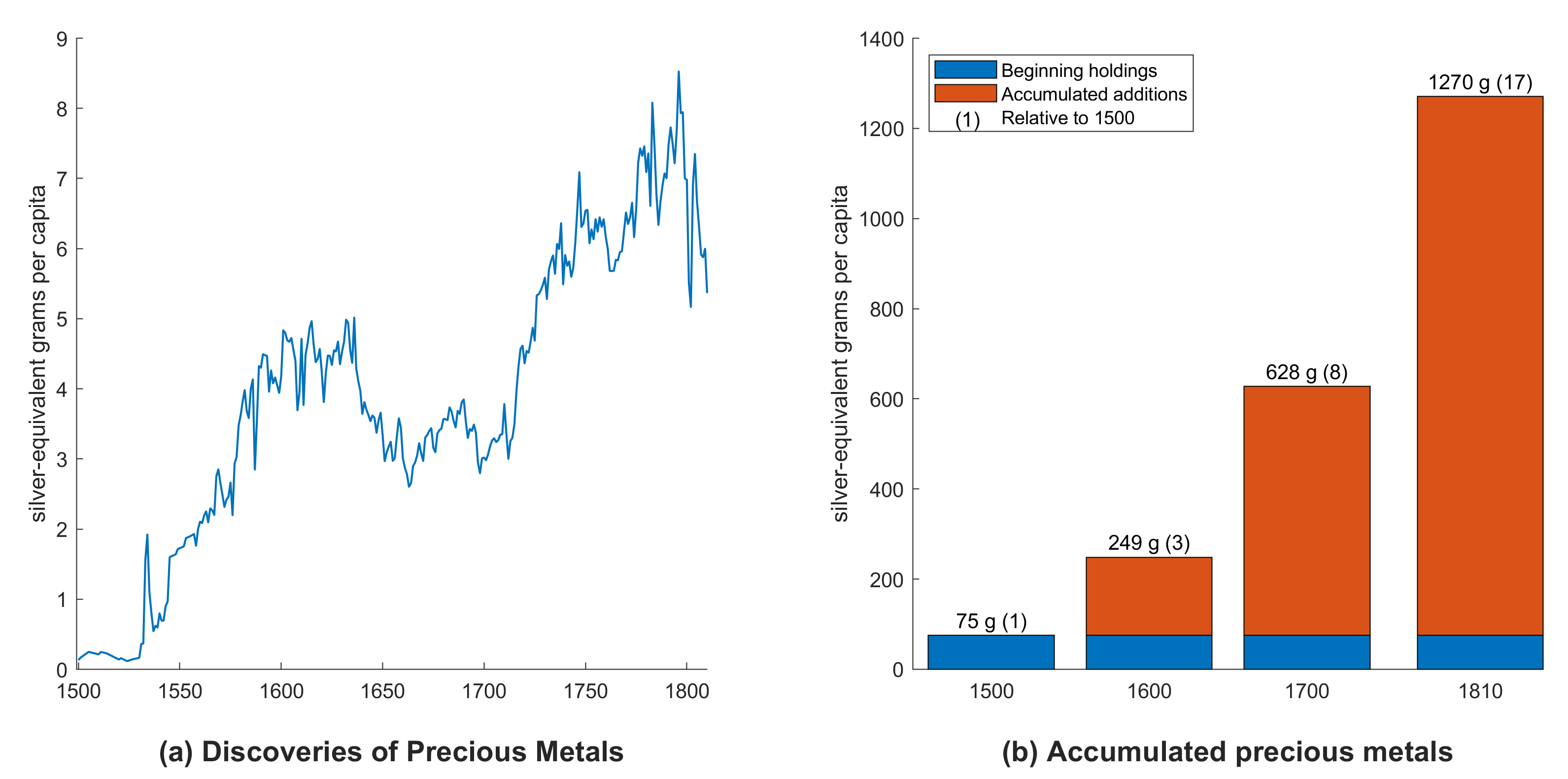

Figure 1 shows data on the production of precious metals of America. Panel a shows annual production per capita. Panel b shows accumulated production over periods of 100 years. By 1810, the production of new precious metals corresponds to 17 times the initial holdings per capita of precious metals. To put this number into perspective, the increase in per capita M1 from January 2008 to January 2012, which includes the period of quantitative easing to curb the financial crisis, was of 1.5 times.

Figure 1 The discoveries of gold and silver in America implied substantial inflows to Europe; by 1810, the accumulated increase was almost 20 times the initial holding of precious metals

Source: Palma and Silva (2024).

Medieval supply of precious metals per capita was approximately constant. Precious metals as a de facto standard implied that prices were stable and that periods of deflation were common. Such a large increase in money supply was unprecedented.

The difficulty is in isolating the effects of the new precious metals from the effects of the new sea routes. Two events happened simultaneously: the discovery of precious metals and new sea routes. Ideally, we would like to compare the situation with the new routes but without precious metals.

This is what we do in a new paper (Palma and Silva 2024). To create the counterfactual scenario of new sea routes but no precious metals, we create a model in which Europe and Asia trade subject to trading costs and in which the population values the services provided by money.

New sea routes are simulated in the model with a decrease in trading costs. A roundtrip from Europe to Asia took three years overland; using the new sea routes, it took months. The voyage was safer, cheaper, and could carry more cargo. The discovery of precious metals is simulated with new money supply directed to the population in Europe. In modern language, it would be equivalent to central bank seigniorage distributed to particular groups, or to the distribution of profits from the ECB to particular countries in the euro area. This is what finding precious metals implied in the period; they were injections of money that Europe could use before the rest of the world.

The two countries have the same characteristics in the model, such as tastes. The only difference between the two regions, apart from their size, is that Europe finds the mountains of gold and silver. Europe alone receives new monetary injections. It is a windfall for Europe.

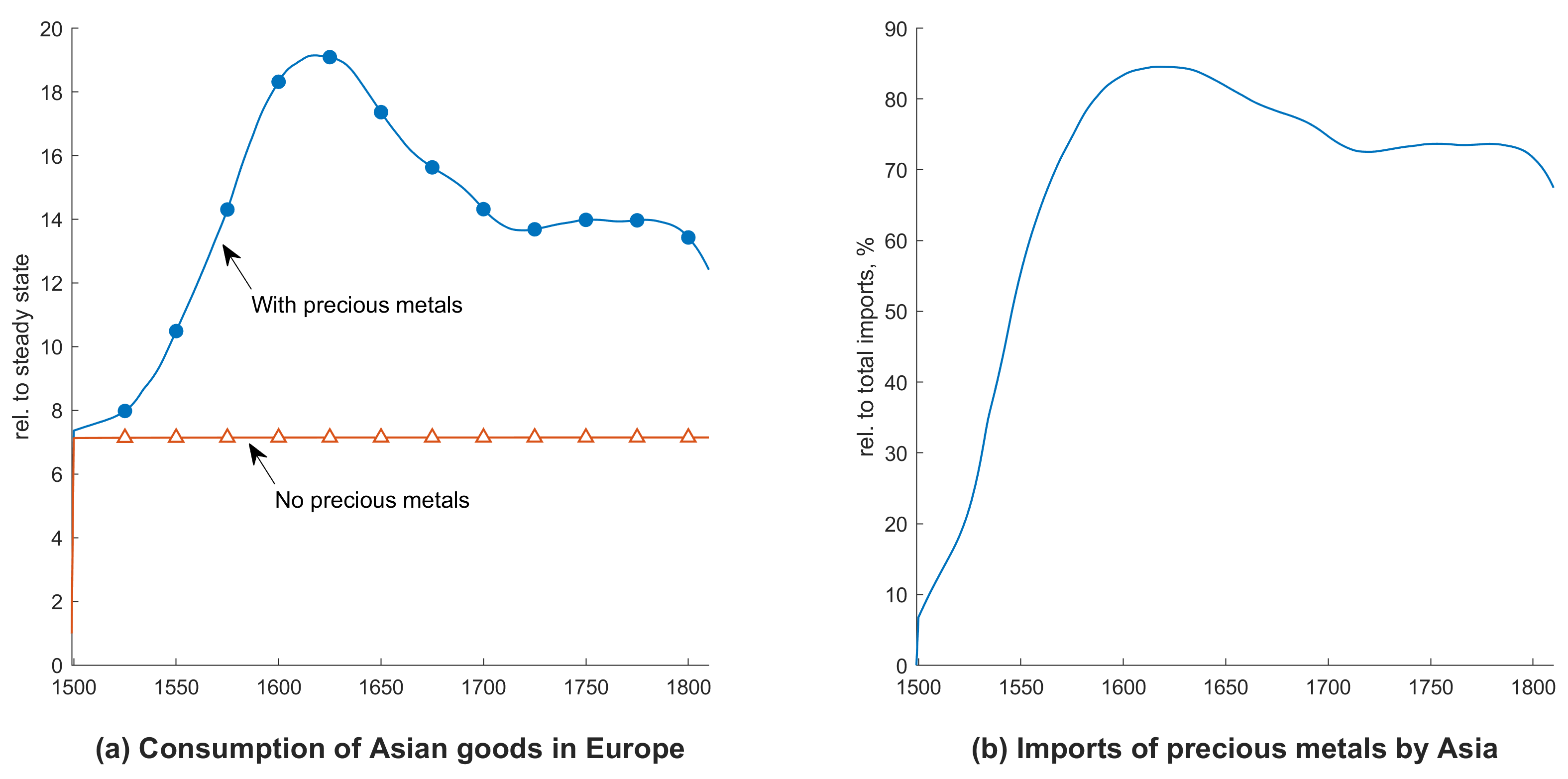

Figure 2 shows the results of the simulations on consumption of Asian goods in Europe (panel a) and on imports of precious metals by Asia (panel b). It is possible with the model to switch off precious metals and compare the observed scenario of new routes and precious metals with the counterfactual scenario of new routes and no precious metals.

Figure 2a New precious metals allowed Europe to increase consumption of Asian goods by 20 times from medieval levels and more than double its level without precious metals (panel a). Most of the imports of Asia were in the form of precious metals (panel b)

Source: Palma and Silva (2024).

Panel a of Figure 2 shows that the consumption of Asian goods in Europe increases by 20 times in comparison with the medieval scenario, before the two breakthroughs of sea routes and precious metals. Without precious metals, the new sea routes alone would have increased consumption seven-fold. The additional increase in consumption stimulated by new precious metals is substantial. In practice, these are imports of silk, tea and porcelain from Asia. On the other hand, panel b shows that the imports of precious metals correspond to more than 70% of the total value of imports by Asia. The model reproduces the fact that outgoing ships to Asia carried precious metals and returned with Asian goods. Precious metals played an important role in the increase in imports from Asia.

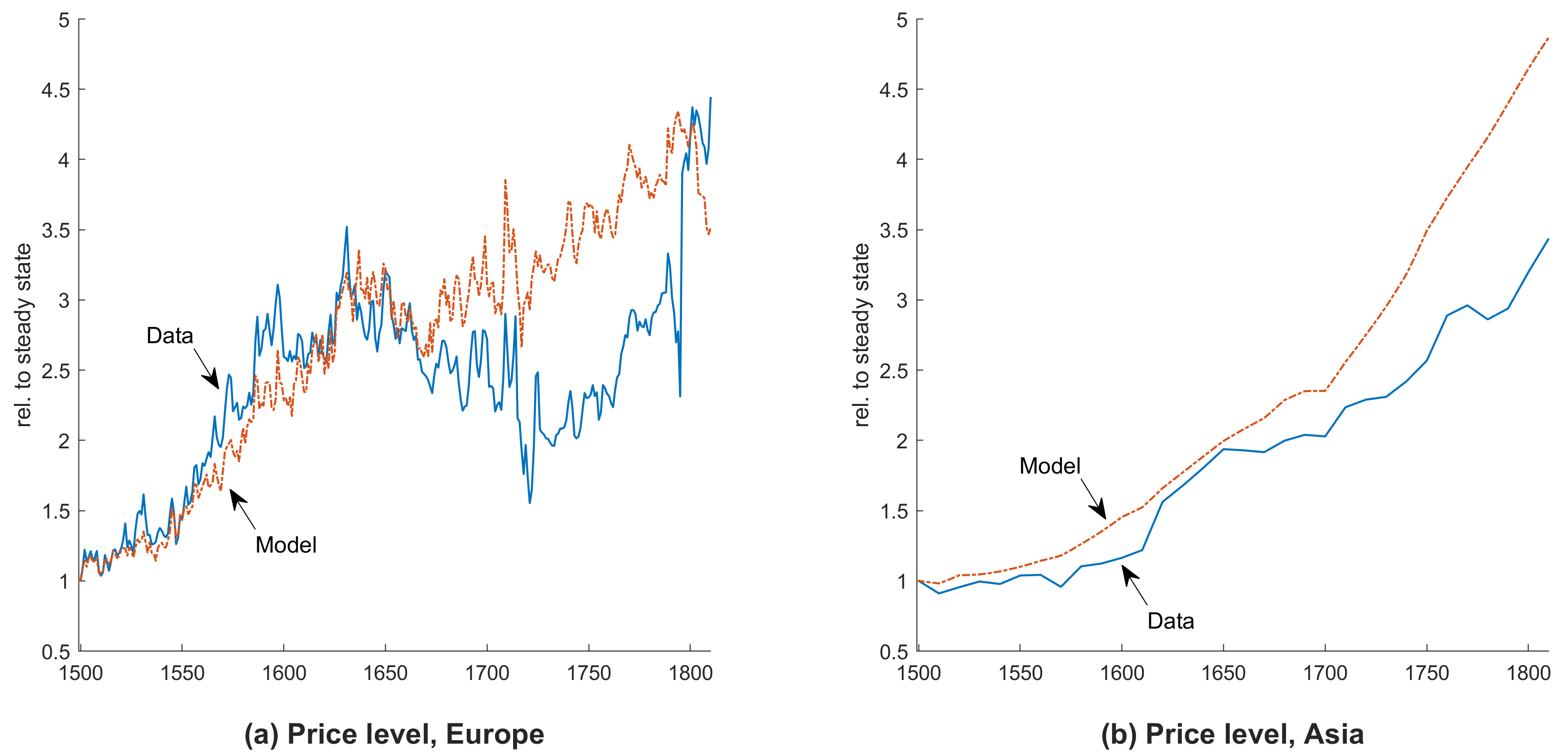

An increase in money supply should imply inflation, and there was indeed world inflation during the period. Figure 3 shows data and the results from the model on the price level in Europe and Asia. The price level is the consumer price index in grams of silver, the monetary standard, as we can have the price level in dollars today. Prices increased by about 4.5 times in Europe during the period (panel a) and took longer to increase in Asia (panel b). Allen (2005) points out that the price level was higher in Europe than in Asia, but the reasons were not clear. We show that the price level increased faster in Europe and this region received the monetary injections first.

Figure 3 New precious metals implied inflation. Annual inflation was lower than today’s usual 2% inflation target, but it was enough to increase prices more than four times. It was a price revolution

That increase in prices had negative welfare consequences. Historically, it was unprecedented. The increase in prices in Europe might have implied instability in the region. Economic historians call this increase in prices a ‘price revolution’ (Hamilton 1934, Munro 2003). Note that an increase in prices of 4.5 times during these 300 years corresponds to 0.5% inflation per year. Enough to imply a price revolution. An inflation target of 2% per year looks too high in comparison with this low rate of inflation.

What is the equivalent of a mountain of gold and silver today? It is the confidence in the dollar and in Treasury bills, with the difference being that this confidence was acquired over time with the management of monetary policy. The confidence makes investors accept dollars and Treasury bills as reserves.

The US has the privilege of paying low interest rates when borrowing but receiving high interest rates when lending. This is possible because the dollar is widely accepted and because the Treasury is able to issue Treasury bills, seen as risk-free, highly liquid, and accepted with low returns. Central banks hold dollars and Treasury bills for their operations. Asia, especially China, accumulated gold and silver in the past. Today, China accumulates Treasury bills in response to high internal savings (Storesletten et al. 2010). Is there an end of the privilege in sight, as alluded to by Heathcote et al. (2022)? Not soon. According to Eichengreen (2023), the share of dollars in foreign exchange reserves is still high.

Borrowing under low interest rates and lending with high returns allows the maintenance of trade deficits. Should China decrease its reserves of dollars and Treasury bills? In the past, there was a trade deficit in Europe with respect to Asia and the accumulation of reserves in the form of silver. At the time, abandoning the silver standard would have been a good policy measure, as China was in fact paying with inflation in silver the demand abroad for its own goods. Abandoning the silver standard earlier would also have been a good policy for China during the great depression, according to Friedman and Schwartz (1963) and Friedman (1992). Total foreign reserves of China totalled $3.3 trillion in 2022 (World Bank 2024). The ‘mountain of gold and silver’ of dollars and Treasury bills finances trade deficits today. It will continue to finance them while confidence in the dollar continues and until internal savings in China allows the accumulation of large reserves.

References

Allen, R C (2005), “Real Wages in Europe and Asia: A First Look at the Long Term Patterns”, in R Allen, T Bengtsson, and M Dribe (eds), Living Standards in the Past: New Perspectives on Well-Being in Asia and Europe, Oxford University Press.

de Vries, J (2003), “Connecting Europe and Asia: A Quantitative Analysis of the Cape Route Trade, 1497–1795,” in D Flynn, A Giraldo, and R von Glahn (eds), Global Connections and Monetary History,1470-1800, Ashgate.

Eichengreen, B (2023), “Is de-dollarisation happening?”, VoxEU.org, 12 May.

Friedman, M (1992), “Franklin D. Roosevelt, Silver, and China”, Journal of Political Economy 100(1): 62-83.

Friedman, M and A Schwartz (1963), A Monetary History of the United States, 1867-1960, Princeton University Press.

Hamilton, E J (1934), American Treasure and the Price Revolution in Spain, 1501-1650, Harvard Economic Studies Vol. 63, Harvard University Press.

Heathcote, J, F Perri and A Atkeson (2022), “The end of privilege: A re-examination of the net foreign asset position of the US”, VoxEU.org, 20 July.

Munro, J H (2003), “The Monetary Origins of the 'Price Revolution': South German Silver Mining, Merchant Banking, and Venetian Commerce, 1470–1540”, in D Flynn, A Giraldez, and R von Glahn (eds), Global Connections and Monetary History, 1470–1800, Ashgate.

Palma, N and A C Silva (2024), “Spending a windfall”, International Economic Review 65(1): 283-313.

Storesletten, K, F Zilibotti and Z Song (2010), “The ‘real’ causes of China’s trade surplus”, VoxEU.org, 2 May.

von Glahn, R (1996), Fountain of Fortune: Money and Monetary Policy in China, 1000-1700, University of California Press.

World Bank (2024), “Total reserves (includes gold, current US$), China” (accessed 12 February 2024).