It is imperative for Russia to lose its war of aggression in Ukraine. Since Ukraine cannot win this war without succour, it is imperative for the other European states to help Ukraine.

Why is it imperative for Russia to lose this war? First, this is a question of international order. Without a supranational entity in Europe that can provide centralised policing and military power, the European post-war order had to be built, again, on a system of explicit and implicit contracts between not-always-free but ever-freer countries. This system was built – more than any of its predecessors – on the principles of territorial integrity and the self-determination of peoples. It is these principles that ensured lasting peace in Europe and also allowed Europe to make its internal borders less onerous to cross, to the extent that they have become almost irrelevant, which, in turn, has given Europe decades of economic prosperity and growth.

Should Russia win its war of aggression in Ukraine, Europe’s foundation and all the prosperity that was built on it will be in jeopardy.

Borders would be important but also violable again. Ukraine’s western-border countries would be in immediate military jeopardy. Even NATO could be, for Russia would only need to wait for another ‘Trump’ in the White House. Russia would continue to influence and manipulate the democratic process and societal dynamics in every other European country. In short, Europe, including Western Europe, would become quasi-vassals to a Russian Empire.

Second, this is a question of economics. In a Europe thus outlined – who would want to invest and innovate there? What would the risk premia be in such an economy? What would Europe’s contribution to the – necessary – global climate-protection transformation be when it lives again on ‘cheap’ Russian fossil energy? After all, why would Russia not want to sell this energy to its periphery? Europe’s brain drain would likely accelerate. Peace dividends would evaporate for a long time.

Third, this is a question of history. I find most plausible the interpretation that this war is the war of an empire attempting to ensure that a perceived periphery state does not venture too far from the centre and its influence. Russia simply cannot afford a prosperous and democratic Ukraine even if Ukraine was not a member of NATO or the EU. The correlate of this is that Putin’s regime models itself not on the Soviet Union, with its internal conservatism and checks and balances, but on the czarist era of great expansion.

What is more, this empire exhibits now open fascism: militarism, manipulative propaganda, clericalism, a surveillance state, the ideology of a ‘New Russia’ rising again from humiliation, genocide, and – increasingly – a death cult, when Putin tells mothers of fallen Russian soldiers, “Your son lived, and his goal has been achieved. And that means he did not leave life in vain” (Reuters 2022). If this sounds familiar, then that’s because it is. The world has heard and seen this in the 1930s from Nazi Germany. Just as the order in Europe had to deal with a German Question in the 19th and 20th centuries, Europe, inevitably, now has to deal with a Russian Question in the 21st century.

Given these stakes, it should almost be unnecessary to discuss the costs of fighting this war, including imposing the harshest of sanctions against Russia and its ability to fight and win this war. Yet, we have heard and read a lot of schlock economics in this debate.

“Germany, and with it Europe, would collapse into mass unemployment and mass poverty if it stopped the import of Russian fossil fuels in the spring of 2022!”

Bachmann et al. (2022), using a multi-sector, multi-country trade model with calibrated input-output and trade structures and substitution elasticities, argued that there would be a recession, but a manageable one, for Germany, not deeper than that during the COVID-19 pandemic. After Russia did stop its exports of fossil fuels in the summer of 2022, little happened to either the German or the European economies: there was, for a price, sufficient alternative supply in the world markets, firms and households could save on energy consumption, and increased imports of energy-intensive products did the rest. Consequently, overall GDP and industrial production numbers were stable, only production in very energy-intensive sectors declined without cascading into the rest of the economy. Doomsday predictions were based on a wrong view of flexible and open market economies, an anti-market ideology, and a lust for subsidies.

“The ruble appreciates again!”

So what? As Itskhoki and Mukhin (2022a,b) have convincingly argued, exchange rate dynamics are influenced by many factors, such as the type of sanctions whether they are levelled against imports or exports, financial frictions, and fiscal policy, and are not a sufficient statistic for welfare.

“Russia can just print its own money to pay for everything!”

This is an example of how modern monetary theory-like thinking can literally cost lives.

“Russia hardly slipped into a recession!”

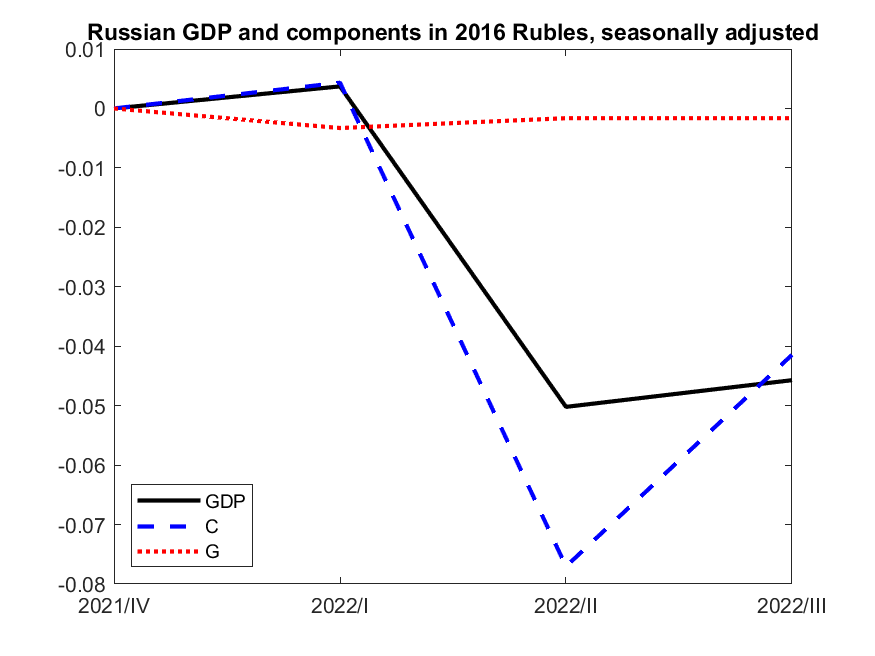

The official Russian national accounting statistics do not support this claim. Although these data may not be fully trusted, they show a decline of real, seasonally adjusted GDP in 2022 from the fourth quarter in 2021 by approximately 5%, and a decline of real, seasonally adjusted private consumption expenditures by approximately 7.5%, while the government expenditures appear to have become an ever larger share of Russia’s GDP (see Figure 1).

These numbers suggest a rather strong decline of real economic activity, which already is remarkable in a time of war that is not waged on its own territory. This decline in real economic activity is accompanied by an even larger decline in Russian average welfare, as marked by the collapse in private consumption as well as the likely massive decline in consumption varieties available to Russians, which corresponds to a decline in welfare that would not necessarily be picked up in the national accounting statistics (see also Morgan et. al 2023).

Figure 1 Russian GDP and components in 2016 rubles, seasonally adjusted

Notes: Real, seasonally adjusted GDP and components in 2016 rubles from Rosstat (2022), Sheet 9. GDP: row 5, C (private consumption) row 8, G (government purchases), row 9.

With so much bad economics, it is almost not worth mentioning that a focus on growth rates rather than levels is also terribly misguided: even if the Western countries had suffered higher GDP or private-consumption losses than Russia because of their sanctions, they would have hit at a much higher level. With concave welfare functions, Russia would still be hurt more.

I want to conclude this column with a personal remark as a German citizen: I submit that Germany has to help Ukraine also from a moral standpoint. I grew up believing that “Never again!” is the core of German civil society and its government after the historically singular atrocities that Germans committed during the Holocaust and during WWII, often on Ukrainian soil. Instinctively, this “Never again!” had always meant “Never again Auschwitz!” or rather, not to relativise the historical singularity that is Auschwitz, “Never again genocidal wars of fascist aggression!”

It is true that a different strand of German public discourse interpreted and still is interpreting the “Never again!” differently, as “Never again war!”, as a form of pacifism that at most allows self-defence. On 13 May 1999, the then German foreign minister and vice-chancellor Joschka Fischer, during a special convention of the Green Party debating the German contribution to NATO’s Kosovo campaign, clarified the “Never again!” position emphatically against its pacifist interpretation. Thus, to me, in light of the historic pain that Germany has inflicted on Ukraine and its people, it is its moral duty to help Ukraine militarily and economically to the utmost.

References

Bachmann, R, D Baqaee, C Bayer, M Kuhn, A Löschel, B Moll, A Peichl, K Pittel, and M Schularick (2022), “What if? The economic effects for Germany of a stop of energy imports from Russia”, ECONtribute Policy Brief No. 028.

Itskhoki, O, and D Mukhin (2022a), “Sanctions and the exchange rate”, VoxEU.org, 16 May.

Itskhoki, O, and D Mukhin (2022b), “Sanctions and the exchange rate”, NBER Working Paper 30009.

Morgan, T J, C Syropoulos, and Y V Yotov (2023), “Economic sanctions: Evolution, consequences, and challenges”, Journal of Economic Perspectives 37(1): 3–30.

Neuenkirch, M, M Repko, and E Weber (2023), “Hawks and doves: Financial market perception of Western support for Ukraine”, IAB discussion paper 1/2023.

Rosstat (2022), GDP statistics, Sheet 9, 29 December.

Reuters (2022), “Putin tells mothers of soldiers killed in Ukraine: ‘We share your pain’”, 25 November.