Across OECD countries, international trade is a major driver of economic growth. Exporting firms earn higher profits, pay higher wages, and grow faster than non-exporting firms (Redding and Melitz 2023, Baldwin and Yan 2015, Melitz and Redding 2015, Schank et al. 2007, Singh 2010, Bernard and Jensen 1999, Bernard et al. 2007). Evidence from the Meta-OECD-World Bank Future of Business Survey undertaken in March 2022 suggests that women entrepreneurs are less likely to engage in international trade, and, as a consequence, are less able to seize opportunities for increasing competitiveness and the other spillover effects international trade offers. Because women are more likely to lead firms in service sectors, and their firms tend to be smaller and younger, they are generally less likely to trade internationally. However, about a third of the gender exporting gap cannot be explained by firms’ features, and instead seems to be associated with factors related to gender differences.

Ensuring that businesses led by women entrepreneurs are able to take advantage of these opportunities will foster gender equality and help to close gender gaps that increased during the COVID-19 pandemic, in addition to contributing to greater and more inclusive economic growth (Ostry and Lagarde 2018). Focusing on this specific category of firms can also help to better tailor policies.

Exporting by entrepreneurs and gender export gaps

Women-led small and medium-sized enterprises (SMEs) are substantially less likely to sell their products and services internationally than those led by men (ITC 2015, ITC 2019, Bélanger-Baur 2019, Ministry of Foreign Affairs and Trade of New Zealand 2022). Only 11% of women-led firms in OECD countries export, compared to 19% of men-led and 13% of equal-led firms, according to the Future of Business Survey.

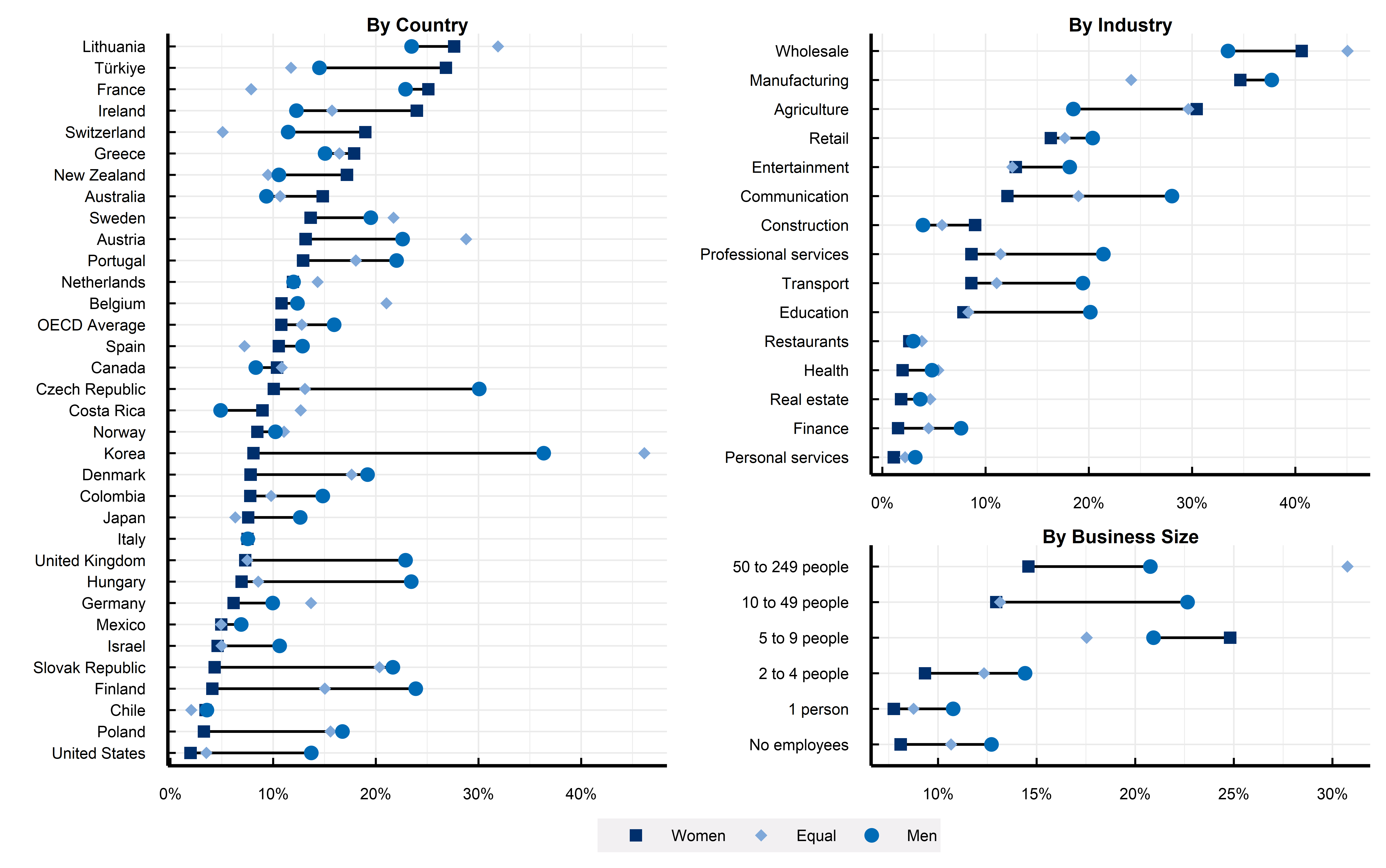

Over the period 2016–2020, less than 9% of women in OECD countries created a business or managed a new business relative to 13% of men (OECD/EC 2021). Women-led firms are less likely to export in most countries, economic sectors, and firm-size categories (Figure 1).

Figure 1 Variation in the gender export gap in firms with a Facebook page

Note: The y-axis displays the share of firms in a given group that indicate they engage in either ‘just exporting’ or ‘both importing and exporting’. Based on a sample of 10,000 SMEs (i.e. firms with fewer than 250 employees) from 34 OECD countries.

Source: Based on the OECD-World Bank-Meta Future of Business Survey from March 2022.

The gender differences in the likelihood to export are due in part to differences in the characteristics of women-led and men-led businesses such as the sectors in which they operate. Women are more likely to lead firms in service sectors (93% of women-led versus 75% of men-led businesses among those surveyed) and services are generally less likely to be traded internationally.

Moreover, women often work in less traded services such as health, education, and public administration.

Evidence shows that services are more costly to provide across borders (Ariu 2012) and policy barriers to services trade are typically higher than barriers to trade in goods such as tariffs (Benz and Jaax 2020).

Women-led firms are generally smaller and younger than those led by men, while exporting is more commonly done by firms that are larger and more established. Only 18% of women-led firms that responded to the survey have more than 50 employees, and 76% have fewer than five, compared to 30% and 66% respectively for men-led businesses in OECD countries. As there can be significant fixed costs for firms to begin exporting, larger companies often find it easier to overcome these hurdles.

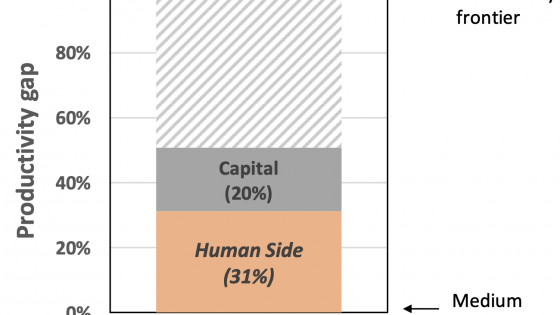

Unpacking the importance of firms’ characteristics on the gender export gap using a Kitagawa-Oaxaca-Blinder decomposition,

we find that 26% is due to the concentration of women-led firms in industries less inclined towards international trade, 27% can be attributed to the smaller average size of women-led firms, 12% is captured by the country of activity, and 1% by business lifespan. This leaves a remaining 34% that cannot be explained by firms’ features, and instead seems to be associated with factors related to gender differences.

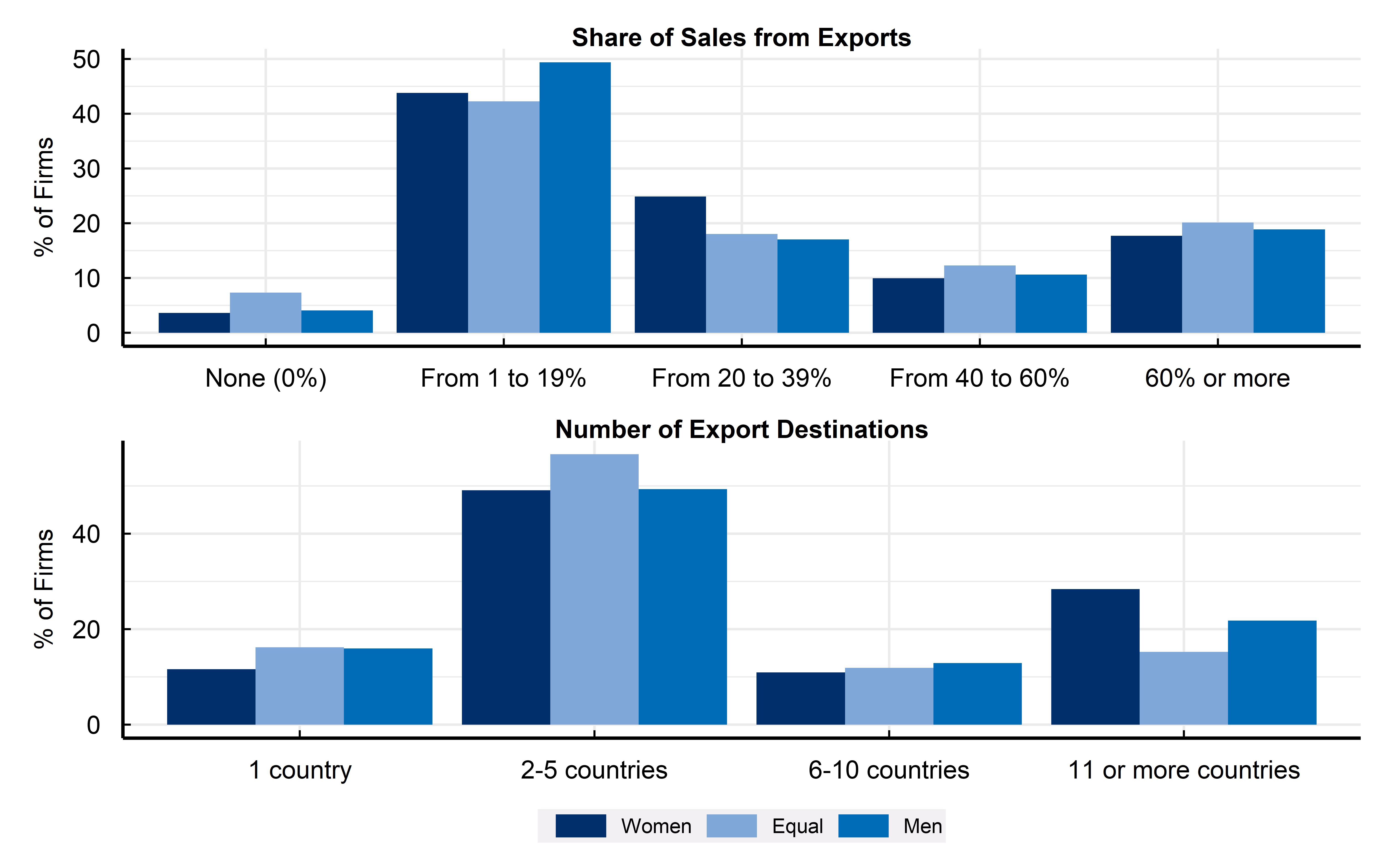

While women-led businesses are generally less likely to export than men-led businesses, those that do sell to foreign markets display similar export patterns to those led by men (Figure 2). Once involved in export, women-led firms do so to a similar or larger number of countries than firms led by men. Twenty-eight percent of women-led firms and 20% of men-led firms exported to 11 or more countries, while 88% of women-led firms and 84% of men-led firms export to more than one country. Moreover, men- and women-led firms that already export see a similar share of their overall sales coming from abroad. This suggests a particular role for policy in helping women-led firms overcome the barriers to beginning their export journey, perhaps even more than providing support to expand their operations.

Figure 2 Export behaviour of exporting firms

Source: OECD-World Bank-Meta Future of Business Survey of SMEs with a presence on Facebook in March 2022.

One striking gender difference in the pattern of foreign sales is that women-led firms tend to export more directly to consumers and less to other businesses. According to the Future of Business Survey, 79% of the men-led firms engaged in exporting report selling to foreign companies, while only 51% of women-led firms do so. Business-to-business sales are often made up of larger orders and therefore offer more opportunity to increase exports along the intensive margin (i.e. increasing the average size of orders). A Kitagawa-Oaxaca-Blinder decomposition of this difference shows it is 18% due to the industries in which these firms operate, 16% due to size differences, and 2% due to the more recent creation of women-led businesses in the survey. Most of the remaining gap – over half of the difference – is not explained by the features of women- and men-led firms.

Women-led firms are at least as engaged online as men-led firms. A larger share of women-led firms’ sales occurs online compared with men-led firms, even when controlling for other firm characteristics. Larger shares of online sales for exporters also underline the importance of digital sales for international trade: firms engaged in international markets are much more likely to use digital platforms compared with those that do not export. Sixty-four percent of women-led firms that export use digital platforms to buy and sell goods and services compared with 37% of women-led firms that do not export. Given the importance of online sales and engagement for international trade, one way to facilitate trade is by ensuring easy and affordable Internet access, including in more remote or rural areas.

Women face a variety of obstacles when it comes to growing their businesses, including less access to financing and less available time due to care obligations (Korinek et al. 2021, ITC 2015). Among the businesses surveyed, 12% of women-led firms currently had a bank loan compared to 20% of men-led firms. This complements other findings such as in the EU, where women entrepreneurs are 25% less likely than their male counterparts to use bank loans to fund their business. Even when they receive external finance, women entrepreneurs typically receive smaller amounts, pay higher interest rates, and are required to secure more collateral (OECD 2022). Other research has found that women-owned firms face 50% more rejections in applications for traditional trade finance than men-owned businesses (DiCaprio et al. 2017). Supporting the growth of women-led businesses by removing barriers to their access to finance will also play a role in enabling them to export.

Women business leaders more often indicated challenges navigating domestic customs procedures and foreign regulations, suggesting a potential knowledge gap that could be filled by export promotion agencies. This finding mirrors the challenge women face in accessing professional networks, which provide information on foreign markets, potential partners, and distributors: women’s professional networks are generally shallower and smaller than those of men (Korinek et al. 2021, Tavares and Sazedj 2022).

Challenges to selling abroad identified by survey respondents can depend on their export status. Firms that already export listed different obstacles than those not yet selling abroad. Both men- and women-led firms that do not yet export are more likely to identify export finance as a barrier than firms already selling abroad. Women-led firms that do not yet trade are more likely to identify understanding foreign markets as an obstacle, while women-led firms that already trade are more likely to point to customs regulations and Internet access as barriers. These findings suggest that the types of policy responses and support needed may be different for firms that are aiming to export compared with those that are looking to expand existing export operations.

Many countries have implemented policies to support women entrepreneurs in their export journey, ensure that trade opportunities are available to them, and lessen barriers to trade and international expansion that particularly impact women. New analysis on women-led businesses in trade (OECD 2023), combined with previous OECD research (Korinek at al. 2021, OECD 2022b) as well as research undertaken in other organisations (World Bank/WTO 2020, ITC 2015, ITC 2020) suggest a number of specific areas of trade policy that can most benefit women entrepreneurs and their businesses. These include:

- Applying a gender lens to trade agreements

- Ensuring market access for goods and services produced and consumed by women and their businesses

- Implementing trade-facilitating measures

- Ensuring inclusive access to the Internet and digital spaces

- Ensuring trade promotion services reach women exporters and cater to their needs

- Providing adequate finance, including trade finance, and promoting financial literacy

- Ensuring professional and business networks are inclusive of women

- Closing data gaps

Examples of programmes and policies that countries have put into place in these areas are outlined in OECD (2023).

References

Ariu, A (2012), “Services Versus Goods Trade: Are they the Same?”, SSRN Electronic Journal, 7 December.

Baldwin, J and B Yan (2015), “Empirical Evidence from Canadian Firm-level Data on the Relationship Between Trade and Productivity Performance”, Statistics Canada.

Bélanger Baur, A (2019), “Women-owned Exporting Small and Medium Enterprises: Descriptive and Comparative Analysis”, Office of the Chief Economist, Global Affairs Canada, draft, 3 October.

Benz, S and A Jaax (2020), “The costs of regulatory barriers to trade in services: New estimates of ad valorem tariff equivalents”, OECD Trade Policy Papers, no. 238, OECD Publishing.

DiCaprio, A, K Kim and S Beck (2017), “2017 Trade Finance Gaps, Growth, and Jobs Survey”, ADB Briefs, no. 83.

International Finance Corporation (2011), “Strengthening Access to Finance for Women-Owned SMEs in Developing Countries”, Washington, DC: IFC.

International Trade Centre (2020), Mainstreaming Gender Provisions in Free Trade Agreements, 8 July.

International Trade Centre (2019), “From Europe to the World: Understanding Challenges for European Businesswomen”, 30 September.

International Trade Centre (2015), “Unlocking Markets for Women to Trade”, 14 December.

Korinek, J, E Moïsé and J Tange (2021), “Trade and Gender: A Framework of Analysis”, OECD Trade Policy Papers, no. 246, OECD Publishing, 26 March.

Melitz, M and S Redding (2015), “Heterogeneous Firms and Trade”, in Handbook of International Economics, vol. 4, 1–54.

Ministry of Foreign Affairs and Trade of New Zealand (2022), “Inclusive and Productive Characteristics of New Zealand Goods Exporting Firms”, MFAT working paper, February.

OECD (2023), “Women-led firms in international trade”, OECD SME and Entrepreneurship Outlook 2023, OECD Publishing, 27 June.

OECD (2022), “Financing Growth and Turning Data into Business”, Helping SMEs Scale Up, OECD Publishing, 7 October.

OECD (2022b), Trade and Gender Review of New Zealand, OECD Publishing, 1 June.

OECD (2021), “Seizing Opportunities for Digital Trade”, Development Co-operation Report 2021: Shaping a Just Digital Transformation, OECD Publishing.

OECD/European Commission (2021), The Missing Entrepreneurs 2021: Policies for Inclusive Entrepreneurship and Self-Employment, OECD Publishing, 29 November.

Ostry, J and C Lagarde (2018), “The macroeconomic benefits of gender diversity”, VoxEU.org, 5 December.

Redding, S and M Melitz (2023), “Trade and Innovation”, VoxEU.org, 28 July.

Schank, T, C Schnable and J Wagner (2007), “Do Exporters Really Pay Higher Wages? First Evidence from German Linked Employer-Employee Data”, Journal of International Economics 72: 52–74.

Singh, T (2010), “Does International Trade Cause Economic Growth? A Survey”, The World Economy 33(11): 1517–64.

Tavares, J and S Sazedj (2022), “The gender gap at the top: The role of networks”, VoxEU.org, 16 July.

World Bank Group and World Trade Organization (2020), Women in Trade: The Role of Trade in Promoting Gender Equality.

World Trade Organisation (2016), World Trade Report 2016: Levelling the Trading Field for SMEs.

Annex: The Future of Business Survey

This column makes use of data from the OECD-World Bank-Meta Future of Business Survey of firms with an online presence on Facebook. The analysis drawn from the survey should be considered relevant to this type of business.

A questionnaire on firm characteristics and economic activity was distributed among a random sample of businesses in March 2022. This resulted in information on almost 10,000 businesses in OECD countries, including whether or not they engage in trade, the gender make-up of their leadership, and other business characteristics such as size and sector of activity.

In the analysis of the survey data, firms are weighted in order to ensure the random sample resembles the population of Facebook page administrators. Since this group is not identical to the wider business population, the survey should be regarded as representative of firms with an online Facebook presence rather than businesses generally.

Firms are defined in this analysis as women-led if they report that the majority of their leadership is women, with the reverse for men, while equal-led businesses are those with a 50-50 division at the time of the survey. Among the surveyed firms, 31% indicated they were women-led, 29% were equal-led, and 40% were men-led.

Gender-differentiated, harmonised data on the total population of businesses by size and sector in OECD countries do not exist, so this survey is one of few data sources that is comparable across countries. Participation in the survey may be skewed towards SMEs although weights are applied to reflect the general population of Facebook business pages. The data used in this analysis refer to micro SMEs (those with fewer than 250 employees).

The firms that are undoubtedly underrepresented in this survey are those that do not have an online presence. Since Facebook is the most prevalent online platform for businesses and the vast majority of businesses that trade have an online presence, it reflects particularly well the firms targeted by this analysis, i.e. SMEs that trade or are trade-ready.