The COVID-19 pandemic triggered a huge, sudden uptake in work from home (WFH), as individuals and organisations responded to contagion fears and government restrictions on commercial and social activities (Adams-Prassl et al. 2020, Bartik et al. 2020, Barrero et al. 2020, De Fraja et al. 2021). Over time, it has become evident that the big shift to WFH will endure after the pandemic ends (Barrero et al. 2021). No other episode in modern history has involved such a pronounced and widespread shift in working arrangements in such a compressed time frame. The Industrial Revolution and the later shift away from factory jobs brought greater changes in skill requirements and business operations, but they unfolded over many decades.

These facts prompt some questions: what explains the pandemic’s role as a catalyst for a lasting uptake in WFH? When looking across countries and regions, have differences in pandemic severity and the stringency of government lockdowns had lasting effects on WFH levels? What does a large, lasting shift to remote work portend for workers? Finally, how might the big shift to remote work affect the pace of innovation and the fortunes of cities?

The Global Survey of Working Arrangements (G-SWA)

To tackle these and related questions, we field a new Global Survey of Working Arrangements across 27 countries. The survey yields individual-level data on demographics, WFH levels, employer plans for WFH levels after the pandemic, commute times, and more. Thus far, we have fielded the survey online in two waves, one in late July/early August 2021 and one in late January/early February 2022. In our new paper (Aksoy et al. 2022), we study full-time workers, aged 20–59 and who finished primary school, and investigate how outcomes, plans, desires and perceptions around WFH vary across persons and countries.

Our G-SWA samples are highly skewed to well-educated persons in most countries. Thus, in making comparisons across countries, we consider conditional mean outcomes that control for gender, age, education, and industry at the individual level, treating the raw US mean as the baseline value. These values should not be understood as averages for the working-age populations or overall workforces in each country. Rather, they are conditional sample means for relatively well-educated full-time workers who have enough facility with smartphones, computers, tablets, and the like to take an online survey.

WFH levels around the world

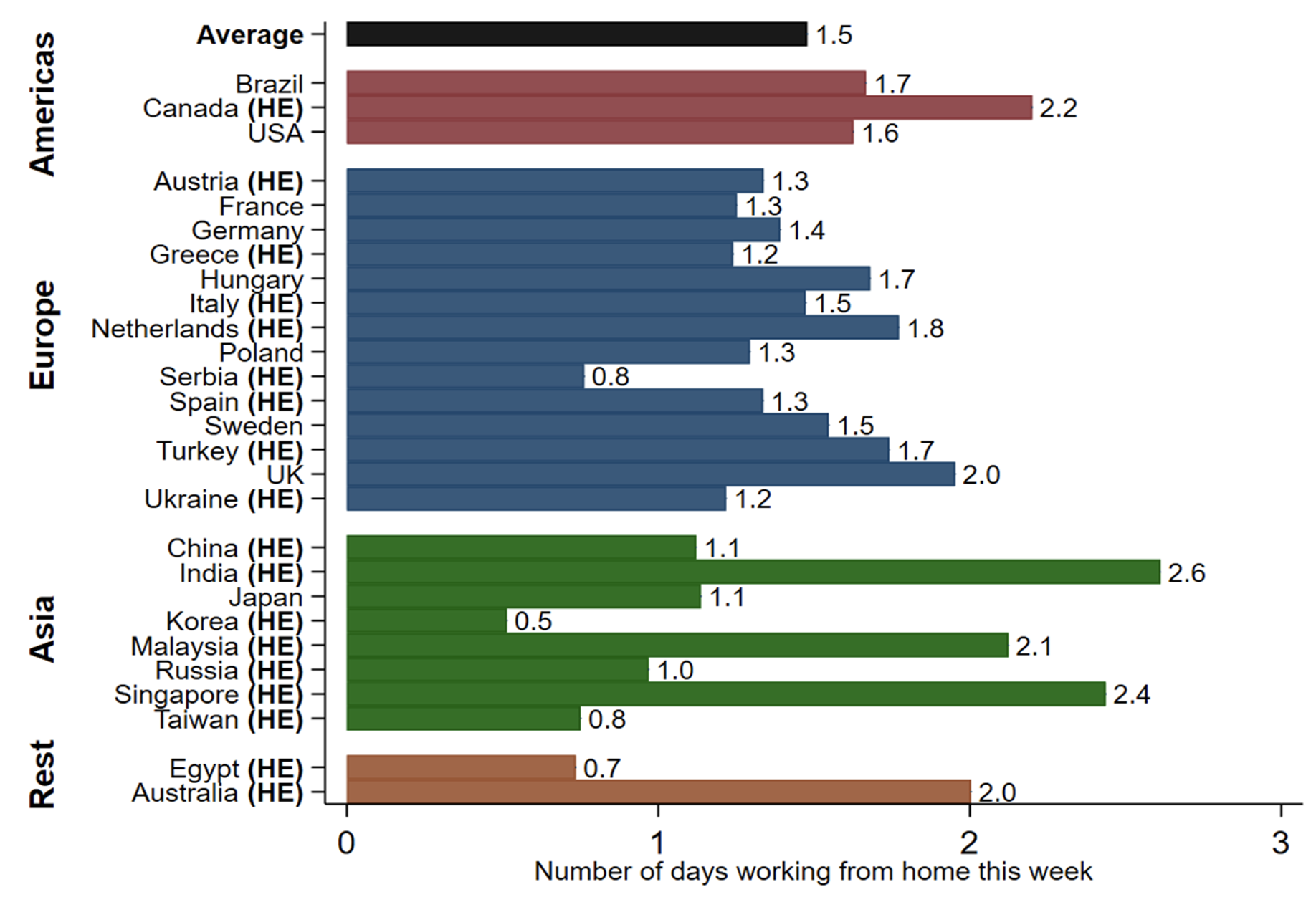

Figure 1 highlights the global nature of WFH among well-educated workers as of mid 2021 and early 2022. It reflects responses to the question, “How many full paid days are you working from home this week?”. Response options range from 0 to 5+ days per week. ‘HE’ next to a country’s name indicates that its G-SWA sample greatly overrepresents highly educated persons.

Figure 1 Working from home is now a global phenomenon among the well educated

Notes: This figure shows country-level conditional means for full WFH days in the survey week. We obtain these conditional means from OLS regressions that control for gender, age (20–29, 30–39, 40–49, 50–59), education (secondary, tertiary, graduate), 18 industry sectors and survey wave, treating the raw US mean as the baseline value. We fit the regression to data for 33,091 G-SWA respondents surveyed in mid 2021 and early 2022. The ‘average’ value is the simple mean of the country-level conditional means. ‘HE’ indicates that the country’s G-SWA sample greatly overrepresents highly educated persons. Sources: Aksoy et al. (2022) and G-SWA.

Full WFH days average 1.5 per week across the countries in our sample. We compute this average as the simple mean of the country-level conditional means. These conditional mean values range widely, from 0.5 days in South Korea, 0.7 in Egypt, 0.8 in Serbia and Taiwan at the low end, to 2.4 in Singapore and 2.6 in India at the high end.

WFH levels will persist beyond the pandemic

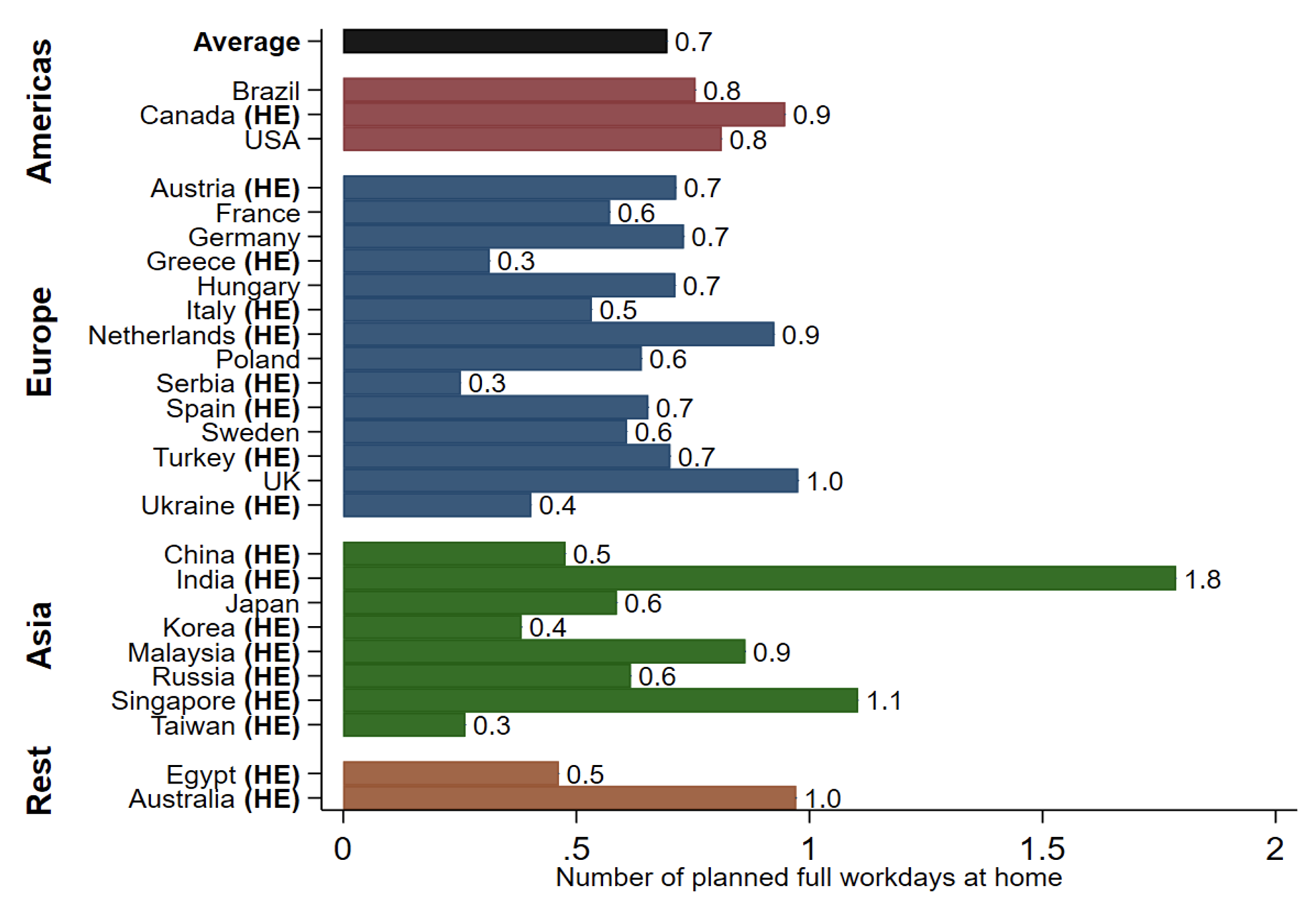

Figure 2 provides direct evidence that high WFH levels will persist beyond the pandemic. The underlying question is: “After COVID, in 2022 and later, how often is your employer planning for you to work full days at home?”. If the worker says his or her employer has neither discussed the matter nor announced a policy regarding WFH, we assign a zero value.

Employers plan an average of 0.7 WFH days per week after the pandemic, ranging from 0.3 days in Greece, Serbia, and Taiwan and 0.4 in South Korea and Ukraine, to 1.0 in Australia and the UK and 1.8 in India. As in Figure 1, there is a wide dispersion in the country-level conditional mean values.

Figure 2 Planned levels of working from home after the pandemic

Notes: This figure shows country-level conditional means, as in Figure 1. We fit the regression to data for 34,875 G-SWA respondents who were surveyed in mid 2021 and early 2022. We limit the sample to persons with an employer in the survey week. The ‘average’ value is the simple mean of the country-level conditional means.

Sources: Aksoy et al. (2022) and G-SWA.

Many workers say they will quit if required to return to the employer’s worksite full-time

We also find that 26% of employees who currently WFH one or more days per week would quit or seek a job that allows WFH if their employers require a return to 5+ days per week onsite. Using SWAA data for US workers, Barrero et al. (2021) find that more than 40% of those who currently WFH one or more days per week would quit or seek a new job if their employers require a full return to the company worksite.

These patterns are in line with other recent empirical evidence. Bloom et al. (2022) conduct a randomised control trial of engineers and marketing and finance employees in a large technology firm, letting some of them WFH on Wednesday and Friday. This hybrid WFH arrangement cut quits by 35% and raised self-reported work satisfaction. After Spotify adopted a ‘work from anywhere’ policy, attrition rates fell 15% in 2022 Q2 relative to 2019 Q2 (Kidwai 2022). This fall coincided with sharply increased quit rates for the overall economy.

The impact of pandemic-induced experimentation on perceptions about WFH productivity

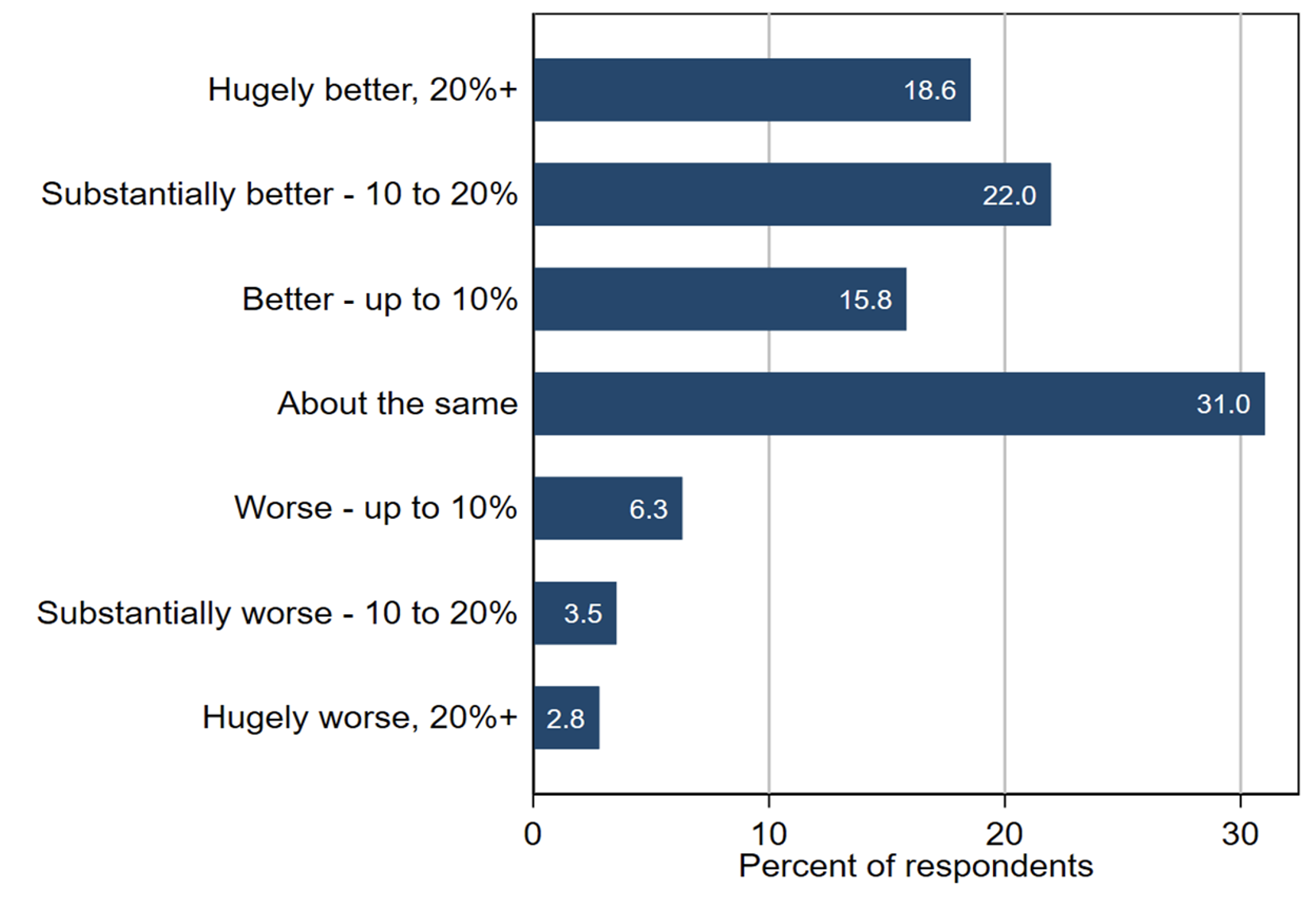

If the survey respondent had WFH experience at some point during the pandemic, we asked: “Compared to your expectations before COVID (in 2019) how has working from home turned out for you?”. Response options are expressed in terms of WFH productivity relative to pre-pandemic expectations (the ‘productivity surprise’). Figure 3 shows the raw response distribution in the pooled G-SWA data.

Figure 3 The distribution of WFH productivity relative to expectations

Notes: This figure shows the distribution of WFH productivity relative to pre-pandemic expectations in a pooled sample of 19,027 respondents who worked from home at some point during the COVID-19 pandemic.

Sources: Aksoy et al. (2022) and G-SWA.

This response distribution has two important features. First, it is highly dispersed. Since WFH levels were quite low before the pandemic – about 0.25 full days per week, according to the American Time Use Survey – wide dispersion in productivity surprises leads to persistently higher WFH levels after the pandemic. Why? Because favourable surprises lead to more WFH in jobs and tasks on the margin, while unfavourable surprises lead to a continuation of near-zero WFH. Second, Figure 3 reveals that pre-pandemic WFH expectations were overly negative for most workers before the pandemic. That is, pandemic-induced experimentation caused most workers to upwardly revise their self-assessed WFH productivity.

Additional analysis of our survey data shows that the conditional mean WFH productivity surprise is positive in all 27 countries – ranging up to 8% or more in Brazil, India, Italy, Spain, Sweden, Turkey, and the US. Supposing that employer and worker assessments are aligned, these revisions in average perceived WFH productivity drive a re-optimisation of working arrangements in jobs and tasks on the margin, contributing to a lasting increase in WFH levels.

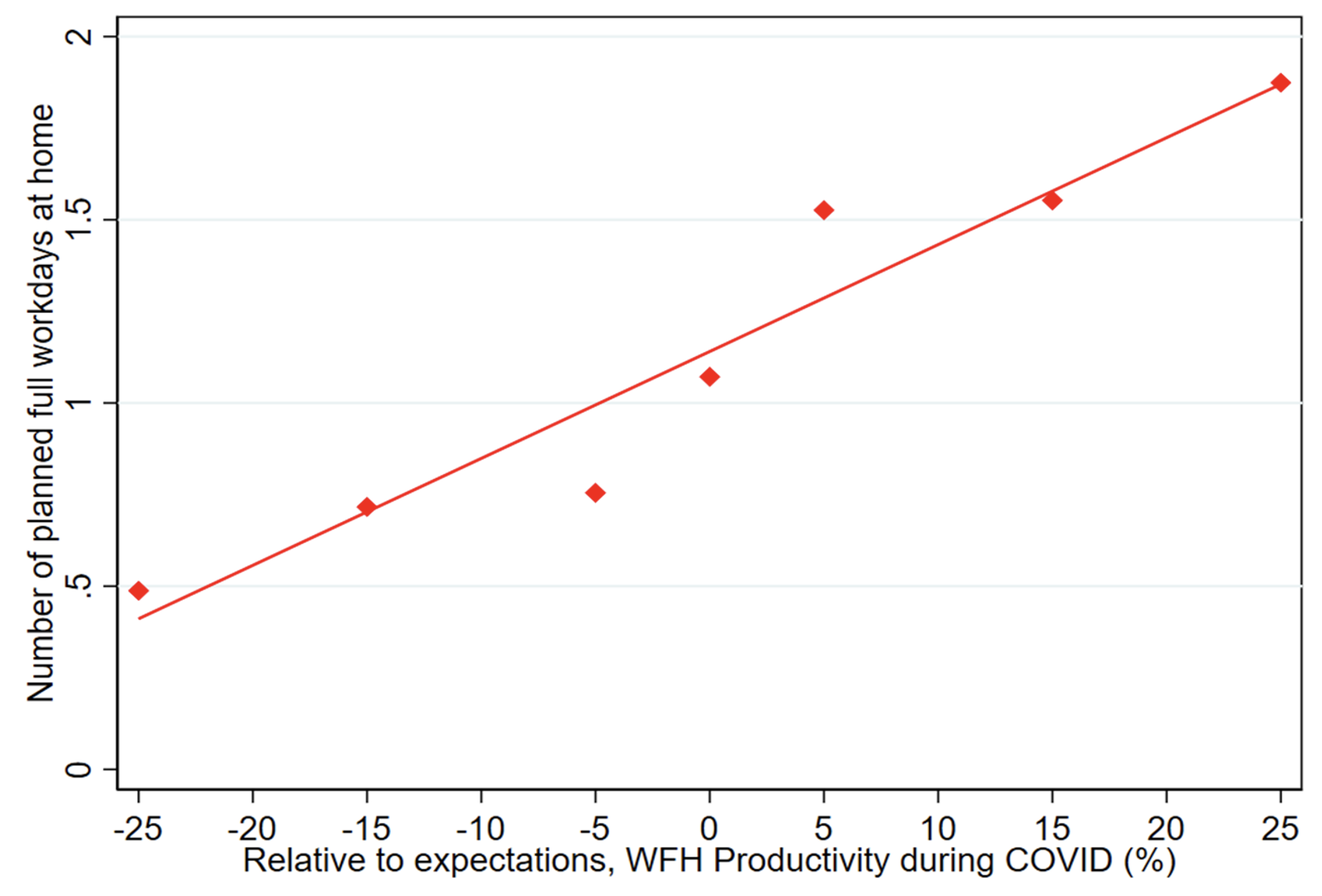

Planned WFH levels after the pandemic rise with WFH productivity surprises during the pandemic

Figure 4 shows the cross-sectional relationship between employer plans and worker-level productivity surprises in the pooled G-SWA data. Planned WFH levels after the pandemic strongly increase with WFH productivity surprises during the pandemic. Moving from the bottom to the top of the surprise distribution involves an increase of about 1.3 days per week in the planned WFH level. This strong positive relationship between WFH productivity surprises and planned WFH levels holds in all 27 countries.

Figure 4 The relationship between employer plans and productivity surprises

Notes: This figure shows the cross-sectional relationship between employer WFH plans and worker-level productivity surprises in the pooled G-SWA data. The underlying survey questions are, first, ‘Compared to your expectations before COVID, how has working from home turned out for you?’ and, second, ‘After COVID, in 2022 and later, how often is your employer planning for you to work full days at home?’ The sample contains 19,027 G-SWA respondents in early 2021 and mid 2022 who worked from home at some point during the COVID-19 pandemic.

Sources: Aksoy et al. (2022) and G-SWA.

Implications

We also develop evidence that the shift to WFH benefits workers. The reason is simple: most workers value the opportunity to WFH part of the week, and some value it a lot. It’s easy to see why. WFH saves on time and money costs of commuting and grooming, offers greater flexibility in time management, and expands personal freedom. Few people could WFH before the pandemic. Many can do so now. This dramatic expansion in choice benefits millions of workers and their families. Women, people living with children, workers with longer commutes, and highly educated workers tend to put a higher value on the opportunity to WFH. Previous studies also document preference heterogeneity around WFH in various settings and using a range of empirical methods (Bloom et al. 2015, Mas and Pallais 2017, Wiswall and Zafar 2018, Barrero et al. 2021, He et al. 2021, Lewandowski et al. 2022).

That does not mean everyone benefits. Some people dislike remote work and miss the daily interactions with co-workers. Over time, people who feel that way will gravitate to organisations that stick with pre-pandemic working arrangements. Another concern is that younger workers, in particular, will lose out on valuable mentoring, networking, and on-the-job learning opportunities. We regard this concern as a serious one but have diffuse priors over whether, and how fully, it will materialise. Firms have strong incentives to develop practices that facilitate human capital investments. Individual workers who value those investment opportunities have strong incentives to seek out firms that provide them. If older and richer workers decamp for the suburbs, ‘exurbs’, and amenity-rich consumer cities, the resulting fall in urban land rents will make it easier for young workers to live in and benefit from the networking opportunities offered by major cities.

Many observers also express concerns about what the rise of remote work means for the pace of innovation. In this regard, we stress that the scope for positive agglomeration spillovers in virtual space is expanding, even as the shift to WFH diminishes agglomeration spillovers in physical space. How these countervailing forces will affect the overall pace of innovation remains to be seen, but our paper sets forth several reasons for optimism.

The implications for cities are more worrisome. The shift to WFH reduces the tax base in dense urban areas and raises the elasticity of the local tax base with respect to the quality of urban amenities and local governance. These developments warrant both hope and apprehension. On the hopeful side, they intensify incentives for cities to offer an attractive mix of taxes and local public goods. Cities that respond with efficient management and sound policies will benefit – more so now than before the pandemic. On the apprehensive side, the economic and social downsides of poor city-level governance are also greater now than before the pandemic. For poorly governed cities, in particular, the larger tax-base elasticity raises the risk of a downward spiral in tax revenues, urban amenities, workers, and residents.

This column only scratches the surface of the evidence and analysis in our paper. All G-SWA data are freely available for use by researchers at https://wfhresearch.com/gswadata/.

References

Adams-Prassl, A, T Boneva, M Golin and C Rauh (2020), “Working from home: the polarizing workplace”, VoxEU.org, 2 September.

Aksoy, C G, J M Barrero, N Bloom, S J Davis, M Dolls and P Zarate (2022), “Working from home around the world”, Brookings Papers on Economic Activity, Fall.

Barrero, J M, N Bloom and S J Davis (2020), “COVID-19 is also a reallocation shock”, Brookings Papers on Economic Activity, Summer.

Barrero, J M, N Bloom and S J Davis (2021), “Why working from home will stick”, NBER Working Paper 28731.

Bartik, A W, Z B Cullen, E L Glaeser, M Luca and C T Stanton (2020), “How the COVID-19 crisis is reshaping remote working”, VoxEU.org, 19 July.

Bloom, N, R Han and J Liang (2022), “How hybrid working from home works out”, NBER Working Paper 30292.

Bloom, N, J Liang, J Roberts and Z J Ying (2015), “Does working from home work? Evidence from a Chinese experiment”, Quarterly Journal of Economics 130(1): 165–218.

De Fraja, G, J Matheson, J Rockey and D Times (2021), “The geography of working from home and the implications for the service industry”, VoxEU.org, 11 February.

He, H, D Neumark and Q Weng (2021), “Do workers value flexible jobs? A field experiment”, Journal of Labor Economics 39(3): 709–38.

Kidwai, A (2022), “Spotify allowed its 6,500 employees to work from anywhere in the world”, Fortune, 2 August.

Lewandowski, P, K Lipowsk and M Smoter (2022), “Working from home during the pandemic: A discrete choice experiment in Poland”, IZA DP No. 15251.

Mas, A, and A Pallais (2017), “Valuing alternative work arrangements”, American Economic Review 107(12): 3722–59.

Wiswall, M, and B Zafar (2018), “Preference for the workplace, investment in human capital, and gender”, Quarterly Journal of Economics 133(1): 457–507.