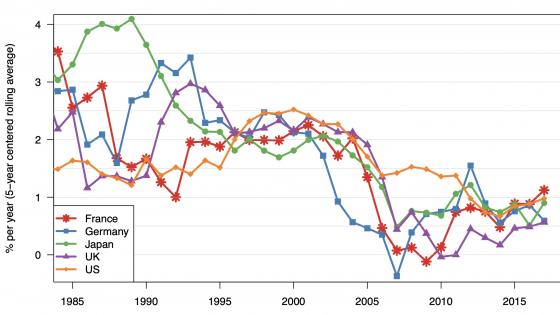

When the COVID-19 crisis hit the world economy in 2020, concerns arose that it would further dampen productivity growth, compounding the poor productivity performance experienced by many OECD economies since the mid-2000s (Winkler et al. 2021). However, the 2023 edition of the OECD Compendium of Productivity Indicators (OECD 2023) shows that most OECD countries experienced a sizeable increase in aggregate labour productivity growth at the onset of the COVID-19 crisis. These results are not a cause for celebration, with temporary factors playing a significant role in 2020, and many of them already receding by 2021.

Aggregate labour productivity figures mask significant heterogeneity across industries. This became evident during the pandemic, as the lockdowns and travel restrictions put in place at that time disproportionately affected some industries. Insights on industry contributions can be obtained with a decomposition of aggregate labour productivity growth into three components: a within-industry effect, accounting for labour productivity growth within each industry, and static and dynamic reallocation effects, capturing the impact of labour resources shifting between industries with different labour productivity levels and growth rates, respectively. The combination of the second and third components forms the overall reallocation effect.

Industry reallocations played a significant role during the pandemic

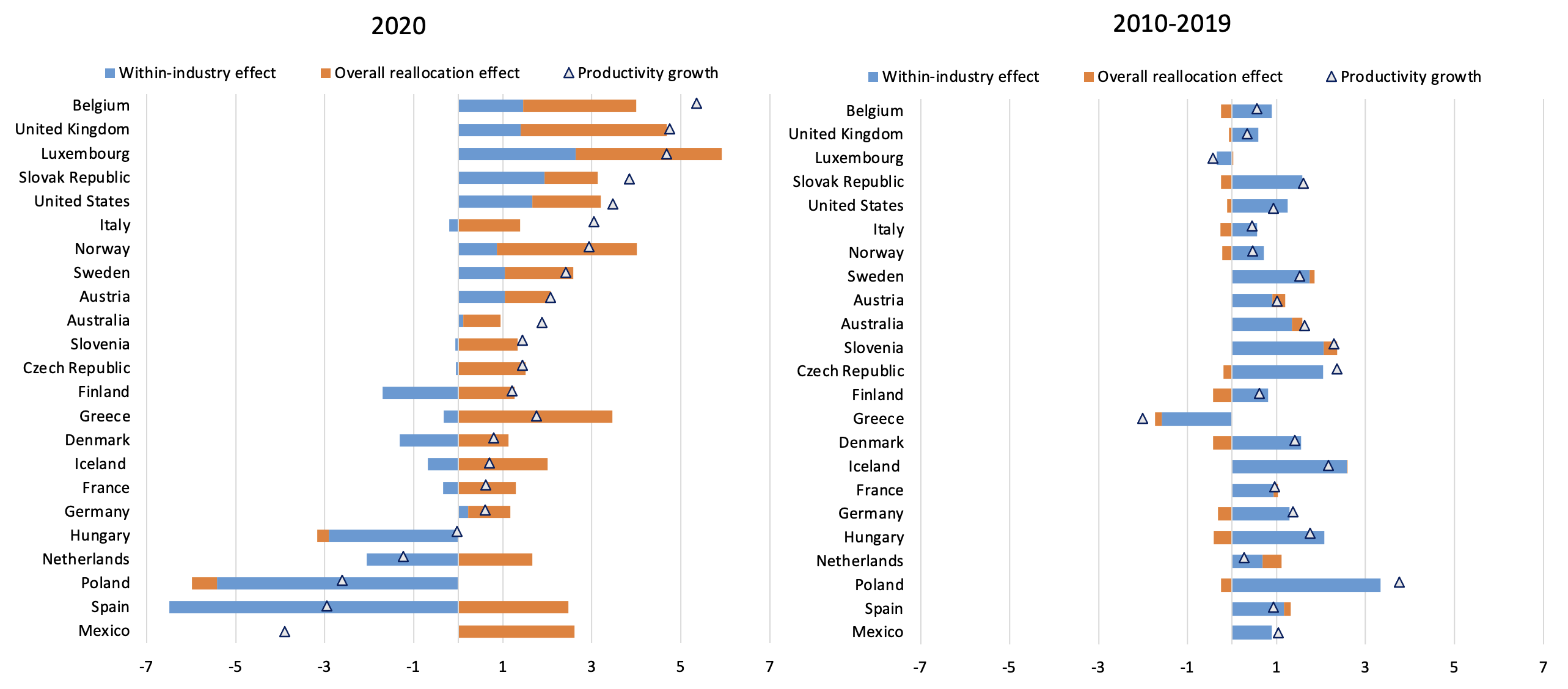

Figure 1 compares the contribution of within-industry and overall reallocation effects to aggregate labour productivity growth across OECD countries in 2020 and 2010-2019. While the overall reallocation effect tends to play a marginal role in normal economic circumstances, its contribution to aggregate labour productivity growth was unusually large in 2020.

Figure 1 Decomposition of labour productivity growth, average annual percentage change

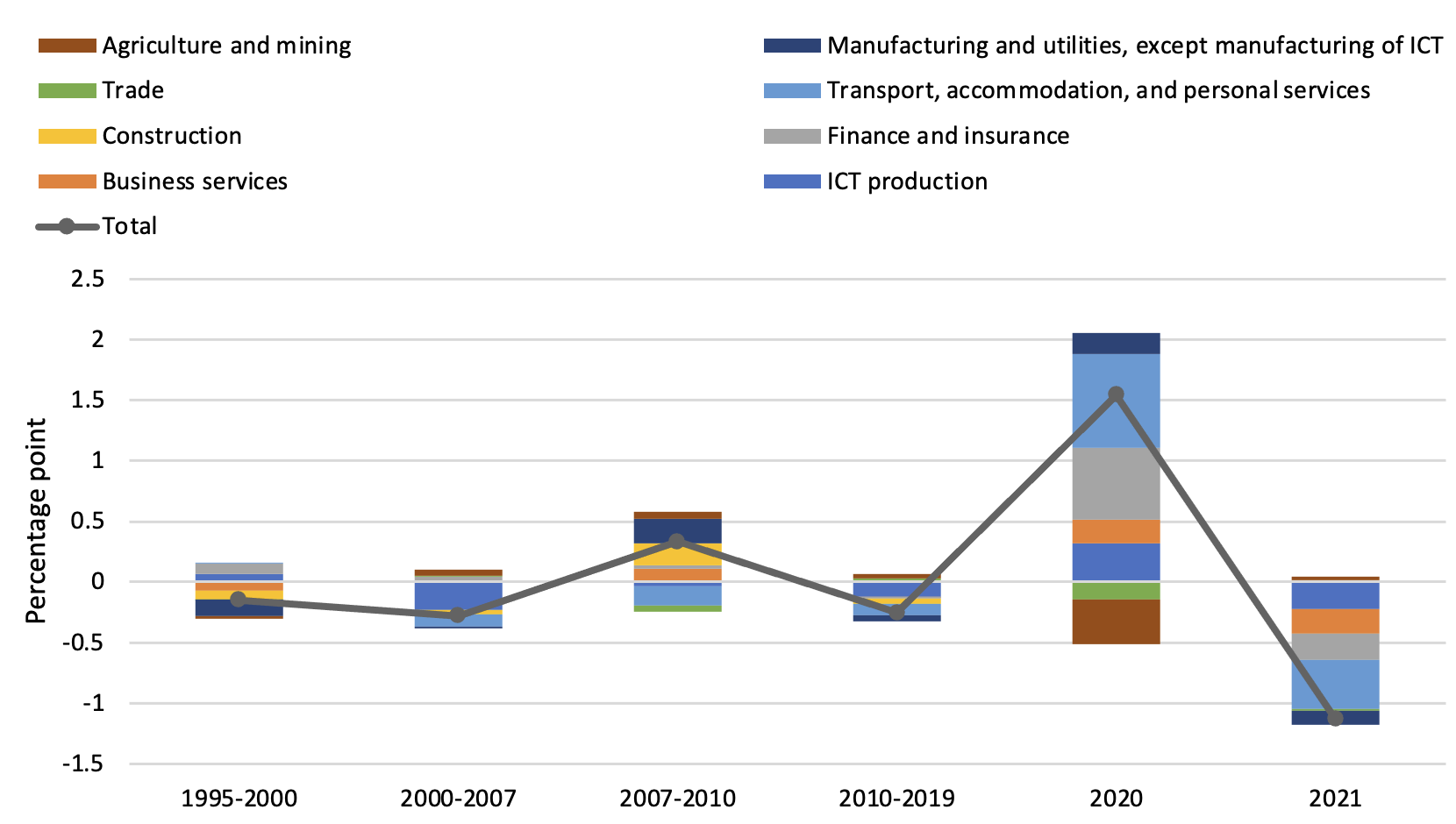

Figure 2 presents a breakdown of the overall reallocation effect into industry contributions for the US.

The 2020 boost in aggregate productivity largely reflected the impact of lockdowns and travel restrictions and the fall in hours worked in a few selected industries, notably transport, accommodation and personal services, whose productivity isbelow average.

Other industries experienced a smaller decline in hours worked in 2020, which had a heterogenous impact on aggregate labour productivity growth. On the one hand, the resilience of economic activity and hours worked in high-productivity industries such as information and communication or finance and insurance, likely related to the rapid deployment of digitalisation and teleworking, helped to boost aggregate labour productivity growth. On the other hand, the limited decline in hours worked in low-productivity industries such as agriculture and construction dampened aggregate labour productivity growth.

Early evidence from the few countries for which detailed industry data are available for 2021 suggests that the reallocation effect observed in 2020 was largely related to temporary disruptions brought by the pandemic. In most cases, the reallocation across sectors started to revert to its pre-pandemic level in 2021.

The rapid increase in job quit rates that followed the first lockdowns, a phenomenon often referred to as the ‘Great Resignation’, was initially thought to reflect a durable change in worker preferences for certain types of jobs (Bloom et al. 2021). However, recent empirical evidence for the US (Hobijn 2022) shows that only a small share of job quitters were actually changing industry of employment or occupation. Additional data for 2021 and beyond will cast more light on the longer-term effects of reallocations induced by the pandemic. Nevertheless, it will be difficult to disantangle these effects from those induced by the green and digital transformations, which are also likely to alter business models and economic behaviours.

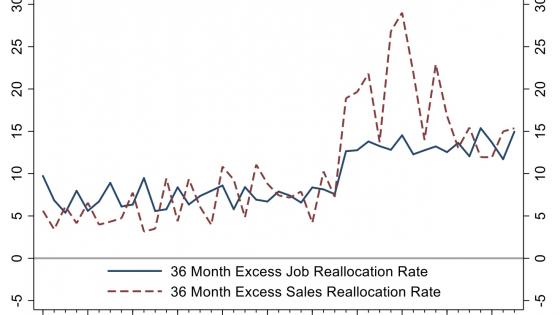

Figure 2 Industry contributions to the overall reallocation effect, US

In normal times, within-industry developments explain most of aggregate labour productivity growth

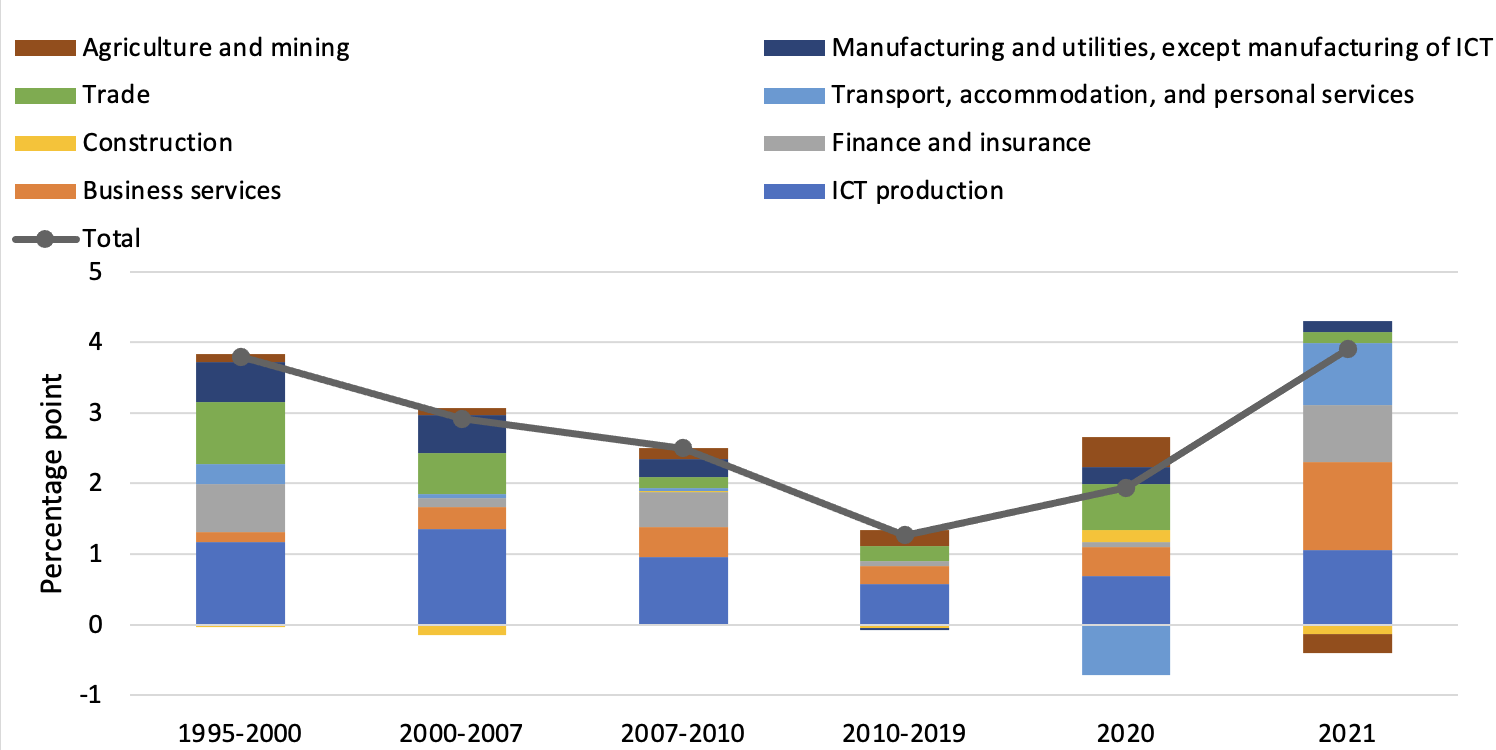

In recent decades, within-industry developments have accounted for most of aggregate labour productivity growth (Figure 3). Information and communication technology (ICT) drove the surge in aggregate labour productivity growth at the turn of the 21st century, most notably in the US (Jorgenson et al. 2008, Cette et al. 2016). This included productivity gains within ICT-producing sectors, as well as the increased use of ICT by some services sectors. Similarly, the slower aggregate labour productivity growth following the ICT-related productivity boom mainly reflected within-industry productivity developments.

In 2020, the within-industry contribution to aggregate labour productivity growth declined further in most OECD countries. In general, transport, accommodation and personal services contributed negatively, while trade, ICT services, finance and insurance, and other business services contributed positively. Nevertheless, the available evidence for 2021 shows that, in a number of countries, the within-industry contribution to labour productivity growth had opposite signs in 2021 and 2020. This will bring back the average contribution in 2019-2021 closer to the value recorded in 2010-2019. The US, where the within-industry contribution was both higher in 2020 than in 2010-2019, and higher in 2021 than in 2020, stands out as an exception among OECD countries (Figure 3).

Figure 3 Industry contributions to the within-industry effect, US

Macroeconomic data, such as those used in the OECD’s 2023 Compendium of Productivity Indicators (OECD 2023), may not fully capture the unusual evolutions of within-industry contributions to labour productivity growth during the COVID-19 pandemic. These data are also subject to revisions, especially in the years 2020 and 2021 when collecting statistical information was challenging due to the pandemic. Firm-level analysis may usefully complement macroeconomic analysis and help unveil the heterogenous impact of COVID-19 on firm performance. This, however, goes beyond the scope of this work.

Authors’ note: This column was written when Pierre-Alain Pionnier was in charge of Prices, Productivity and Labour statistics in the OECD Statistics and Data Directorate

References

Bloom N, S David and J M Barrero (2021), “Let me work from home, or I will find another job”, VoxEU.org, 27 July.

Cette G, J G Fernald and B Mojon (2016), “The Pre-Great Recession Slowdown in Productivity”, European Economic Review 88: 3-20.

Hobijn, B (2022), “Great Resignations are Common during Fast Recoveries”, FRBSF Economic Letter No. 2022-08.

Jorgenson D W, M S Ho and K J Stiroh (2008), “A Retrospective Look at the U.S. Productivity Growth Resurgence”, Journal of Economic Perspectives 22(1): 3-24

OECD (2023), OECD Compendium of Productivity Indicators 2023, OECD Publishing.

Winkler J, P Koutroumpis, F Lafond and I Goldin (2021), “Re-evaluating the sources of the recent productivity slowdown”, VoxEU.org, 31 May.