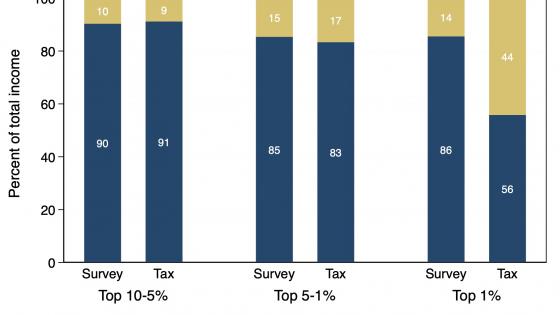

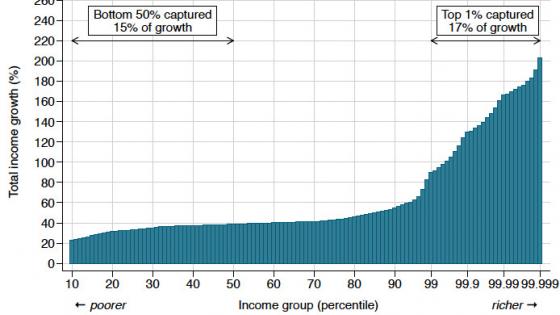

The growing share of household income going to the top of the distribution has been revealed by studies exploiting data from the administration of income taxes (Atkinson et al. 2011). This has called into question the reliance of much inequality research and official monitoring on household surveys, as these may fail to adequately capture those top incomes. Yonzan et al. (2022), for example, report a substantial and growing gap for the US between the top 1% share from the Current Population Survey versus tax records.

If the extent of this gap varies across countries and over time, neither country comparisons nor time trends from surveys will be reliable. To see whether this is a substantial problem, one needs to look across a broad set of countries over a significant period in surveys that are themselves as comparable as possible.

Assessing the scale of the problem across European countries

This is what we do in Carranza et al. (2022) using microdata from the national surveys carried out within a common framework comprising EU-Statistics on Income and Social Conditions (EU-SILC), the EU’s key source for inequality and social inclusion statistics. We exploit the fact that methods to adjust for the ‘missing top’ have been developed and applied to EU-SILC data in the context of the World Inequality Database’s Distributional National Accounts (WID DINA) (Blanchet et al. 2019, 2021, 2022), aligning with top shares estimated from tax data.

WID DINA output relates for the most part to adults not households, to income that is not ‘equivalised’ to take differences in household size and composition into account, and to income concepts that diverge from standard survey-based measures of gross and disposable income. This means that one cannot see from the copious DINA output what implications their top income adjustments have for conventional inequality measures. We address this by going back to the EU-SILC microdata, applying (an adapted version of) those top income corrections, and deriving ‘corrected’/adjusted figures for inequality as conventionally measured in surveys.

The impact of adjusting for the ‘missing top’ in EU-Statistics on Income and Social Conditions (EU-SILC)

Our results show, first, that adjusting the top of the income distribution to align with estimates from tax data makes a substantial difference across the 26 EU-SILC countries and years for which external tax-based top income estimates are available. Averaging across the country-years, the Gini coefficient for disposable income expressed in percentage terms, which in the surveys typically lies in the range 30-35, increases by 2.3 ‘Gini points’. The share of income going to the top 1% – typically 5-6% in the surveys – increases on average by two percentage points. These are substantial average effects.

What is even more striking is that the adjustment has much more impact for some countries than others. Belgium, Iceland, Germany, Poland, Romania, Switzerland, and the UK see an average increase of 4–6 Gini points and a 3.5–5.5 percentage point increase in the top 1% share. By contrast, some other countries – including Denmark, Greece, Ireland, Italy, and Sweden – see almost no change in the Gini or top 1% share on average over the years covered.

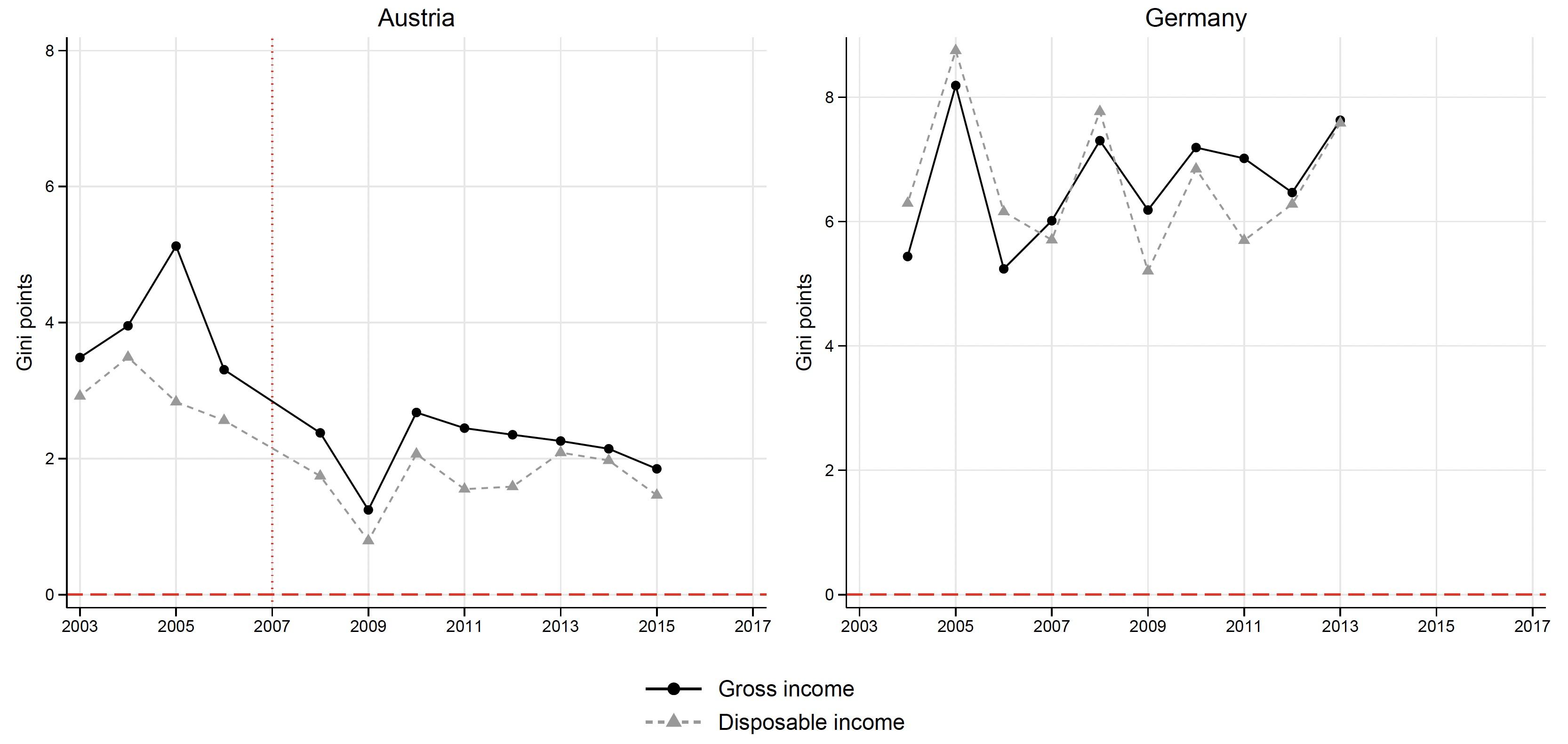

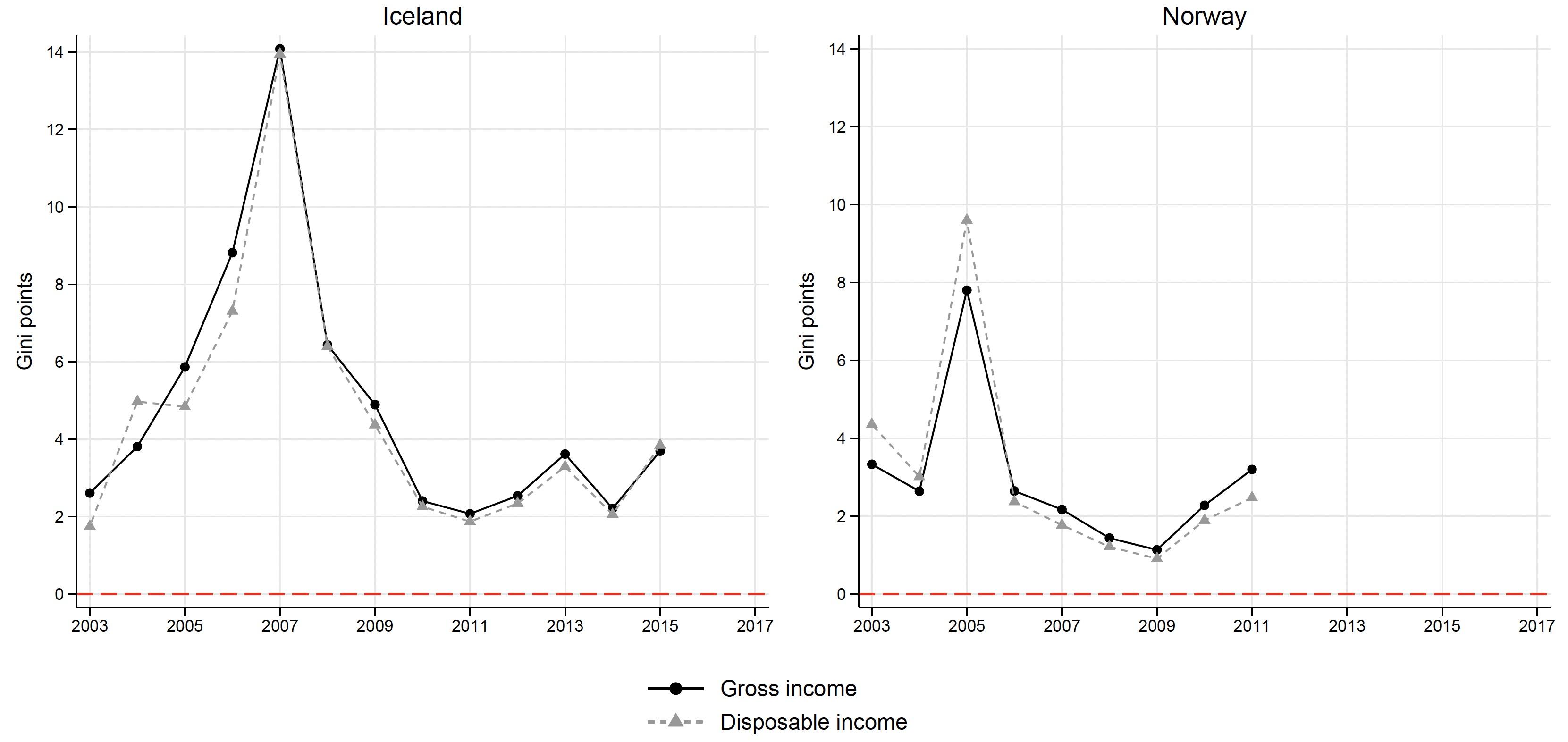

There is also a good deal of variation over time in the impact of the adjustment for some countries. To illustrate, Figure 1 shows the impact on the Gini coefficient for Austria and Germany and Figure 2 shows the impact for Iceland and Norway. For Germany, the adjustment always increases the Gini very substantially by between six and eight Gini points with no clear trend. For Austria the impact is less but still substantial, initially of the order of 4–5 Gini points, but in more recent years down to about two points. For Iceland the impact is mostly 2–4 Gini points but very much higher around the financial crisis. For Norway the impact is also generally in the 2–4 range but twice that in one specific year.

Figure 1 Impact of top income adjustment on the Gini coefficient for gross and equivalised disposable income, EU-SILC for Austria and Germany

Figure 2 Impact of top income adjustment on the Gini coefficient for gross and equivalised disposable income, EU-SILC for Iceland and Norway

These patterns point first to an important aspect of the national surveys in EU-SILC and more generally: these vary widely in the extent to which they link to and draw on administrative data from the income tax and social security systems, and this capacity has also been increasing for some countries over time. One would expect that for surveys that do so, the top income adjustment would have less impact, and this is what we find on average. Countries that make little or no use of linkage to administrative data such as Germany, Poland, and Portugal are among those where the adjustment has the most substantial effect, while some countries that have had this capacity to a high level from the outset such as Denmark see very little impact. It is also the case that in some countries – including Austria – increasing use of administrative data over time may have contributed to a declining top adjustment impact. However, some countries making extensive use of administrative data, which is the case for both Iceland and Norway, still see the adjustment having a substantial effect in some or all the years covered.

The particularly sharp fluctuations there also bring out the sensitivity of tax-based estimates to circumstances such as Iceland’s dramatic financial boom and bust and for Norway a specific change in the taxation of dividends. The latter echoes the conclusion of Yonzan et al. (2022) that changes in the US tax code were a significant contributor to the widening of the gap between survey and tax-based estimates there. The nature of the tax statistics, what they do and do not capture, and how that changes over time, thus needs to be kept to the fore.

Taken with other recent studies of top incomes in EU-SILC by Hlasny and Verme (2018) and Bartels and Metzing (2019), basing top income adjustment on external data rather than relying on within-sample characteristics appears to matter more than the technical approach adopted.

Implications

These findings highlight that the problem of the ‘missing top’ in household income surveys is salient to an extent that varies even in developed economies across surveys that are co-ordinated and carried out within a common framework. This complicates significantly the monitoring, comparison, and analysis of income inequality levels and trends and the understanding of underlying causal processes at work.

From an EU perspective, a two-track strategy seems warranted. On the one hand, the linkage of the EU-SILC surveys to administrative data needs to be further encouraged and facilitated, to exploit the potential for this linkage to improve the ‘capture’ of top incomes and limit the need for post-survey adjustment. However valuable, this does not seem likely to be a ‘magic bullet’ that solves the problem, as it still relies on the original population surveyed and may struggle to fully capture income from capital in particular. At the same time, then, ‘adjusted’ summary inequality measures could be produced to accompany the current unadjusted indicators for those countries where available tax statistics provide a suitable basis for that adjustment. In doing so, both the myriad ways in which tax-based statistics diverge from survey approaches to income measurement and the nature and limitations of those tax-based measures themselves need to be fully taken into account.

More broadly, responding to the challenges that surveys face in adequately capturing the top of the income distribution means exploiting administrative sources as very valuable complementary information. An in-depth understanding of the strengths and limitations of both sources in each specific national case is required as they are brought together to better represent the income distribution.

References

Atkinson, A B, T Piketty and E Saez (2011), “Top Incomes in the Long Run of History”, Journal of Economic Literature 49(1): 3–71.

Bartels, C and M Metzing (2019), “An Integrated Approach for a Top-Corrected Income Distribution”, Journal of Economic Inequality 17(2): 125–143.

Blanchet, T, L Chancel and A Gethin (2019), “Forty Years of Inequality in Europe”, VoxEU.org, 22 April.

Blanchet, T, L Chancel and A Gethin (2021), “Why Is Europe More Equal Than the United States?“, American Economic Journal: Applied Economics, forthcoming.

Blanchet, T, I Flores and M Morgan (2022), “The Weight of the Rich: Improving Surveys Using Tax Data”, Journal of Economic Inequality 20: 119-150.

Carranza, R, M Morgan and B Nolan (2022), ‘Top Income Adjustments and Inequality: An Investigation of EU-SILC”, Review of Income and Wealth.

Hlasny, V and P Verme (2018), “Top Incomes and Inequality Measurement: A Comparative Analysis of Correction Methods Using the EU SILC Data”, Econometrics 6(2): 1–21.

Yonzan, N, B Milanovic, S Morelli and J Gornick (2021), “Mind the gap: Disparities in measured income between survey and tax data”, VoxEU.org, 05 November.

Yonzan, N, B Milanovic, S Morelli and J Gornick (2022), “Drawing a Line: Comparing the Estimation of Top Incomes Between Tax Data and Household Survey Data”, Journal of Economic Inequality 20: 67-95.