As the EU climate policies are getting increasingly stringent, it is becoming more expensive for the European firms to continue emitting CO2. The price of emission allowances within the EU Emissions Trading System (EU ETS) increased from €10 to more than €100 per tonne of CO2 between early 2018 and early 2023. With firms facing higher carbon costs, this factor is becoming more important for market pricing of firms with different degrees of carbon intensity. If the stock market punishes high emitters and rewards low emitters in response to carbon price changes, this reinforces the effectiveness of climate policy in redirecting financing towards sustainable activities.

First empirical studies on the relationship between companies’ stock performance and the carbon price were published a few years after the launch of the EU ETS in 2005 (Oberndorfer 2009, Mo et al. 2012). Subsequent papers extended the analysis by gradually increasing the period and the number of firms included in the sample (Oestreich and Tsiakas 2015, Tian et al. 2016). At that stage there was no clear consensus in the literature as to the sign of the stock price-carbon price relationship. Results differed depending on the choice of countries, companies, periods, and analytical approaches. At the same time, most papers concluded that the magnitude of the relationship is fairly small: a 1% change in the carbon price tends to coincide with a stock price change of only a few basis points. Another broadly confirmed result is that the interaction between stock and carbon price changes is not stable over time. This evolution is typically explained by changes in the rules governing the EU ETS.

More recent studies provide more consistent evidence on how firms’ stock prices are affected by carbon price changes. Ramelli et al. (2018) showed that investors rewarded highly emissive US firms following a sudden shift to less stringent climate policy after President Trump’s election in 2016. Bolton and Kacperczyk (2021a, 2021b) show the presence of a ‘carbon premium’ that investors demand from firms with a higher exposure to carbon risk. Finally, Hennge et al. (2023) found empirical evidence that policy announcements which increase carbon prices have a negative effect on the stock prices of carbon-intensive firms.

How large are firms’ carbon related costs?

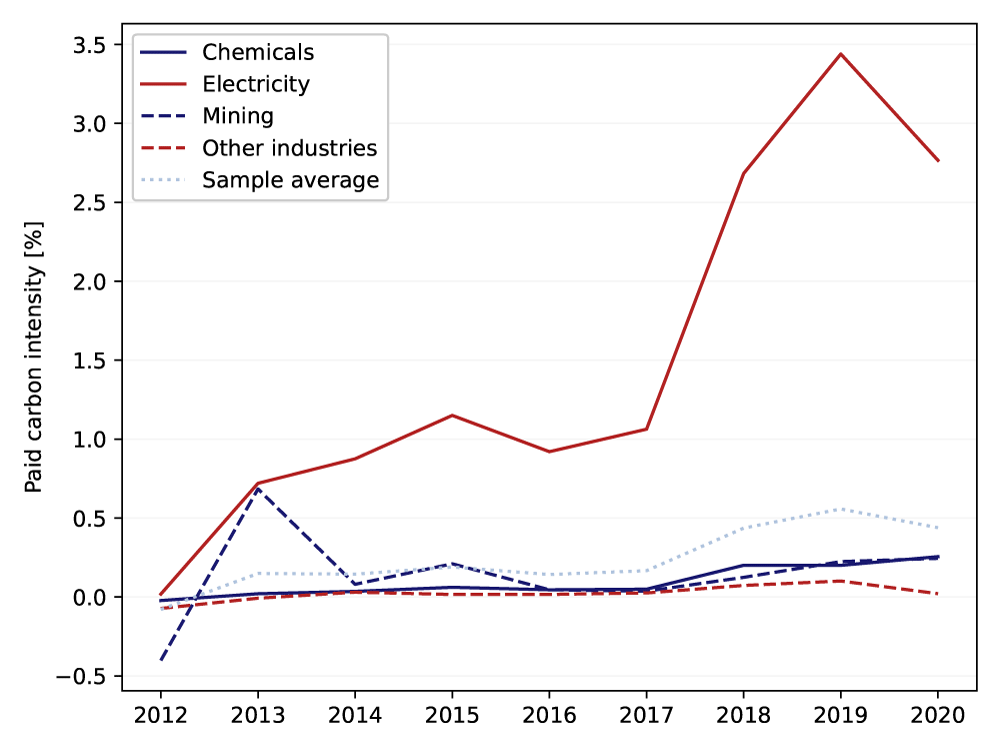

In our recent paper (Millischer et al. 2022) we analyse a novel dataset of more than 300 publicly traded EU companies covered by the EU ETS. Specifically, we explore the relationships between EU companies’ stock performance and changes in the carbon price. The European power generating sector is particularly exposed to the developments on the carbon market. Since 2017, its spending on emissions allowances

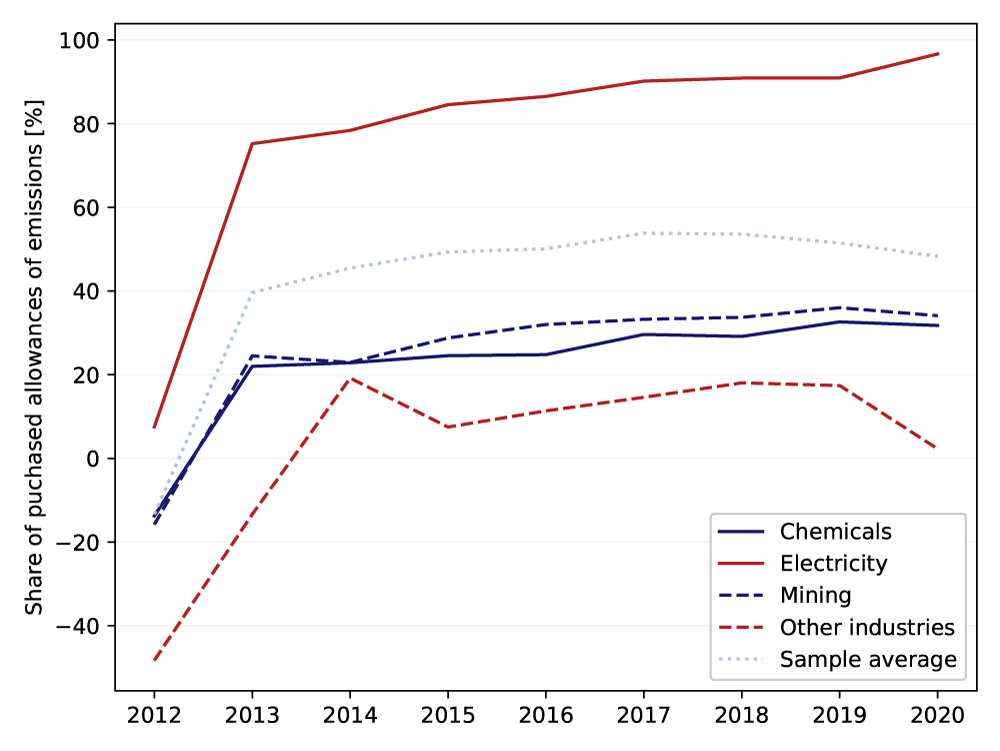

has jumped from around 1% to more than 3% of turnover (Figure 1). For most companies from other sectors the carbon costs do not exceed 0.5% of their turnover. This difference between the scale of exposure is linked to varying carbon pricing approach across sectors. Indeed, companies in sectors other than power generation still get the majority of their emission allowances for free (Figure 2). These sectors (such as steel and cement production) tend to be more exposed to competition from outside the EU, so the EU hands out free allowances to them to avoid replacing domestic production with imports (the ‘carbon leakage’ effect).

Figure 1 Paid carbon intensity by industry (% of turnover)

Figure 2 The share of purchased emission allowances in total emission allowances (%)

How do markets price in firms’ carbon costs?

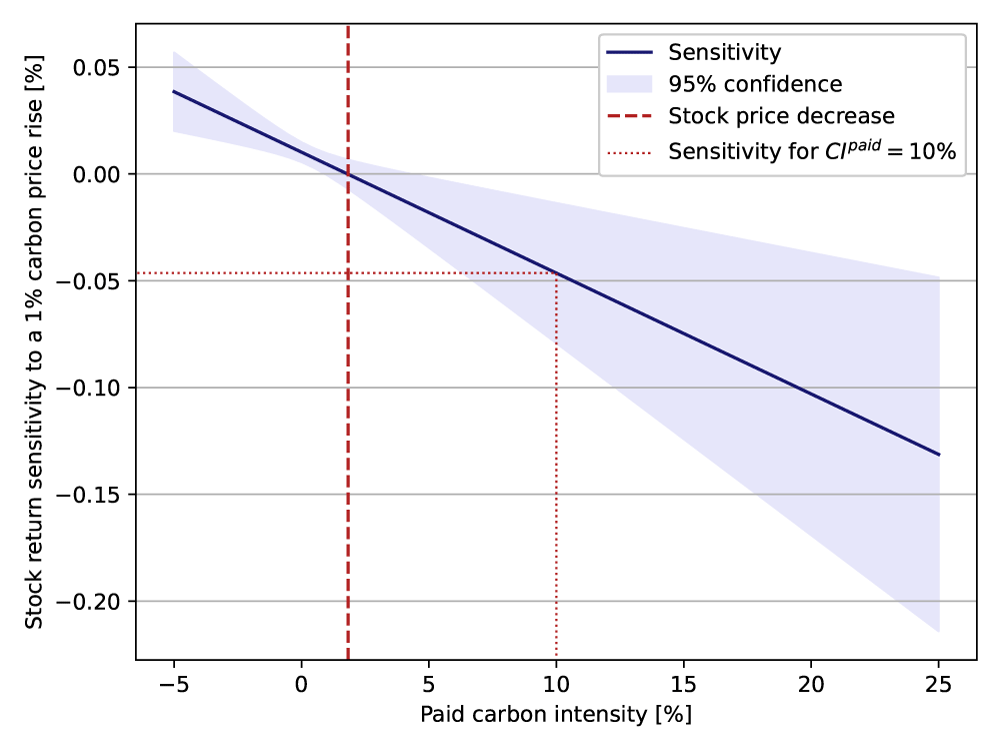

Our paper significantly expands the period and the number of companies in the sample and finds a clear link between companies’ stock performance and changes in the carbon price, which depends on firms’ carbon intensity. The relationship is statistically significant. Stocks of carbon-intensive firms tend to underperform stocks of cleaner peers when the price of carbon increases. While most firms see their stock price actually increase if carbon prices increase (Figure 3) – probably because they benefit from higher prices passed on to consumers without incurring commensurate carbon costs – polluting firms with carbon costs above 1.7% of turnover will see their stock price decline. This effect is persistent and particularly strong in the power generating sector and in the countries with the highest carbon costs. The effect has also intensified in the recent period of rapid carbon price increases.

Figure 3 Sensitivity of the stock return to a 1% increase in carbon price as a function of the paid carbon intensity

Crucially, we show that markets price in only the costs of purchased emissions allowances, while emissions covered by the allowances allocated to the firms for free do not affect the relationship between carbon prices and stock returns. In other words, stock markets do not seem to care about the overall level of firms’ emissions but only about their fraction that has a direct impact on firms’ profitability. Markets do price in the size of emissions covered by free allowances only on the days (identified by Kanzig 2022) when regulation regarding free allocation is updated. This makes sense given that more stringent rules on free allocation increase transition risks for polluting firms that do not yet have to pay much for their emissions.

Room for more ambitious climate policies

Our results suggest that simple emissions data disclosure might not be enough to improve markets’ ability to channel funds towards more sustainable projects. Once combined with a carbon pricing scheme, however, it creates a quantifiable incentive channel for shareholders and management to decarbonise firms’ operations. More ambitious carbon pricing policies could strengthen these incentives.

Higher carbon costs for firms within the EU ETS can be achieved in three ways. The first is by making sure the price of allowances continues to rise. While in a cap-and-trade system direct price control is impossible, strengthening the Market Stability Reserve or introducing an explicit price floor, as suggested by Ohlendorf et al. (2022), would have such an effect. The second is by phasing out free allowances. This could be done quickly for domestic air travel without impact on competitiveness and gradually for the manufacturing sector alongside the introduction of a carbon border adjustment. The third way is by subjecting further sectors to the EU ETS – currently, heating, transport, agriculture, and waste management are largely excluded from the scheme.

The EU ETS provides incentives for firms to decarbonise, including, as we have shown, via their stock prices. The EU should strengthen such incentives. The EU’s experience can guide other countries considering implementing carbon pricing schemes of their own.

References

Bolton, P and M Kacperczyk (2021a), “Do investors care about carbon risk?”, Journal of Financial Economics 142(2): 517–549.

Bolton, P and M Kacperczyk (2021b), “Global Pricing of Carbon-Transition Risk”, VoxEU.org, 24 March.

Hengge, M, U Panizza and R Verghese (2023), “Carbon policies and stock returns: Signals from financial markets”, VoxEU.org, 6 June.

Kanzig, D R (2022), “The unequal economic consequences of carbon pricing”, Working Paper.

Millischer, L, T Evdokimova and O Fernandez (2022), “The Carrot and the Stock: In Search of Stock-Market Incentives for Decarbonization”, IMF Working Paper No. 2022/231.

Mo, J-L, L Zhu and Y Fan (2012), “The impact of the EU ETS on the corporate value of European electricity corporations”, Energy 45(1): 3–11.

Oberndorfer, U (2009), “EU emission allowances and the stock market: Evidence from the electricity industry”.

Oestreich, A M and I Tsiakas (2015), “Carbon emissions and stock returns: Evidence from the EU Emissions Trading Scheme”, Journal of Banking & Finance 58: 294–308.

Ohlendorf, N, C Flachsland, G F Nemet and J C Steckel (2022), “Carbon price floors and low-carbon investment: A survey of german firms”, Energy Policy 169, 113187.

Ramelli, S, A F Wagner, R Zeckhauser and A Ziegler (2018), “Stock price rewards to climate saints and sinners: Evidence from Trump’s election”, VoxEU.org, 29 October.

Tian, Y, A Akimov, E Roca and V Wong (2016), “Does the carbon market help or hurt the stock price of electricity companies? further evidence from the EU ETS context”, Journal of Cleaner Production 112: 1619–1626.