A productivity increase which leads to a higher hourly wage may affect hours worked through two channels: an income channel (hours worked decrease when productivity increases) and a substitution channel (hours worked increase). The number of hours worked per worker could itself affect productivity per hour. Here again, two channels are involved: a fatigue effect implying decreasing returns of working time, and a fixed-cost or learning-by-doing effect implying increasing returns of working time.

A non-consensual economic literature

There is no consensus in the empirical literature regarding the circular relationship between productivity and hours worked.

Concerning the impact of productivity on hours worked, using country-level data from a set of 15 OECD advanced countries over the period 1963–2006, Reif et al. (2021) estimate a positive impact of productivity growth on hours worked. This means that for these specific data, the substitution channel prevails over the income channel. Another strand of literature estimates through vector auto-regression (VAR) or structural VAR (i.e. SVAR) models the impact of total factor productivity TFP shocks on hours worked. For instance, Li (2022) finds, by such an approach on US data from 1948 to 2017, a significant and negative impact, which means that the income channel outweighs the substitution channel. Bick et al. (2018) and Bick et al. (2022b) claim, using country panel data, that the relation between the hours worked on average per worker and the GDP per capita corresponds to an inverted U curve. The average number of hours worked per worker first rises with the GDP per capita and then decreases beyond a certain development level.

Concerning the impact of worked hours on productivity, whilst the literature is consensual in admitting non-constant returns to scale of hours worked, it is not consensual in concluding as to whether those returns are increasing or decreasing. A fatigue effect could explain decreasing returns to scale of hours worked whereas fixed-cost and learning-by-doing effects could explain increasing returns of hours worked. As detailed by Eden (2021), this impact of hours worked on productivity per hour depends also on many things, such as the length of the working day, the number and the position of the vacation days in the week and the year, etc. On different country-level datasets of advanced countries over the last decades, Bourlès and Cette (2007), Aghion et al. (2009), Cette et al. (2011), and Bourlès et al. (2012) estimate on average decreasing returns to scale of hours worked of about 50%. Using different datasets for the UK for the early 20th century, Pencavel (2015) estimates a fatigue effect and consequently decreasing returns of hours worked. These decreasing returns reportedly become large on exceeding 49 hours of work per week. Using individual US data, Bick et al. (2022a) estimate increasing returns to hours worked when workers are on short hours (below 40 hours per week) and decreasing returns for long hours (above 48 hours a week).

We use two original databases …

In Cette et al. (2023), we analyse the circular relationship between productivity and worked hours, distinguishing between short-term and long-term mechanisms. This empirical investigation draws on Bergeaud et al.’s (2016) very long-term productivity panel database: our country-level estimation sample covers a very long period from 1891 to 2019 for 21 advanced countries. We supplement our analysis using the EUKLEMS & INTANProd industry level database. The corresponding panel sample is unbalanced and covers 22 advanced countries and 23 business sectors for the more recent period 1995–2019.

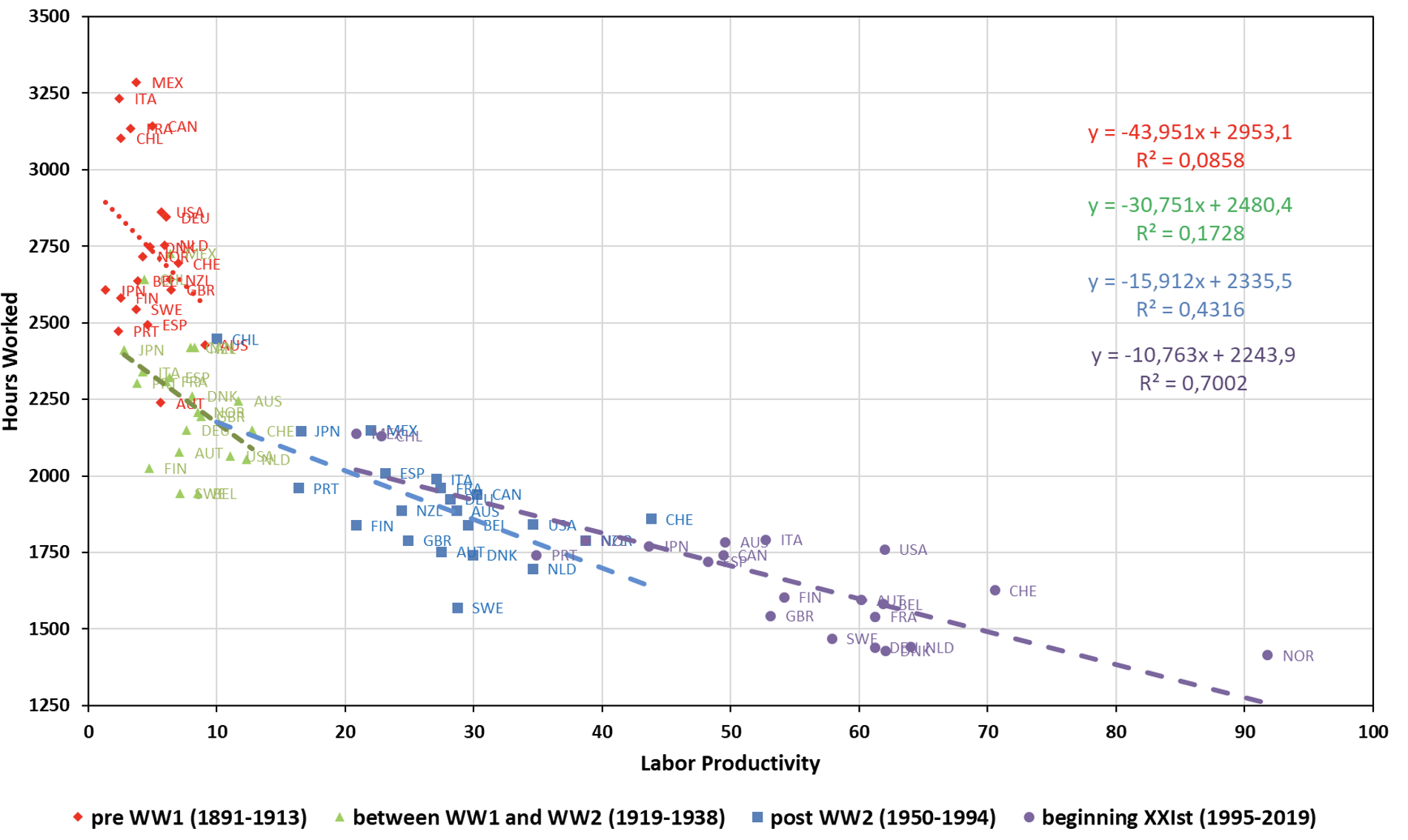

Figure 1 plots the long-run relationships between hours worked and labour productivity at a country average level. The average values for our 21 countries are displayed for our four main sub-periods: before WWI (1891–1913), between the two World Wars (1919–1938), after WWII (1950–1994), and around the turn of the 21st century (1995–2019). The relationships obtained are always negative and level off for more recent sub-periods. These relationships are consistent with the existing literature: hours worked tend to decrease and labour productivity to increase over time. In a long-run framework and considering only variations between countries, the income channel seems to outweigh the substitution channel.

Figure 1 Hours worked and labour productivity: Country averages (21) over four sub-periods (country-level database)

Notes: Each point represents a specific country for one sub-period. For this specific country, we represent the average value of labour productivity and hours worked over this sub-period. In the top right corner, linear equation regressions and R2 values are given for each sub-period (earliest sub-period at the top). Series used for GDP and capital are given in 2010 constant national currencies and converted to US dollars at purchasing power parity (PPP).

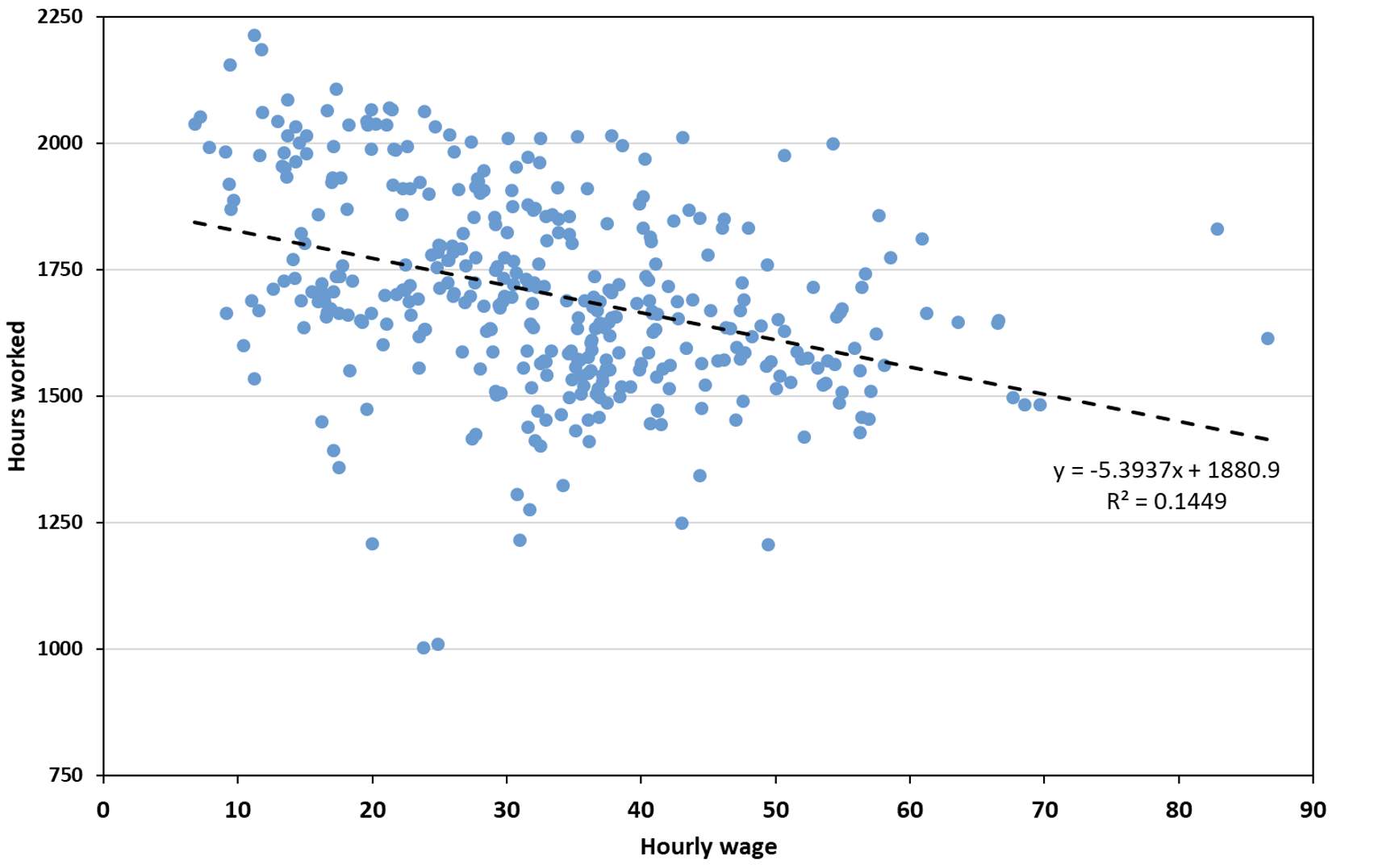

Figure 2 plots the relationship between real wages and hours per worker using country-industry averages from the industry level database. It suggests a negative relationship between hours worked and wages, which is consistent with the relation between hours worked and labour productivity shown in Figure 1 on country level averages.

Figure 2 Hours worked and hourly wage: Country-by-industry average, period 1995–2019 (industry-level database)

Notes: Each point represents a country-industry specific average for the period 1995–2019.

… to estimate the circular relationship between productivity and worked hours

We have estimated the two relations of the circular relationship distinguishing between short-term and long-term mechanisms. This empirical investigation draws on the two databases mentioned before. Estimations are performed using the instrumental variable (IV) approach to avoid endogeneity problems. Estimation results obtained through IV methods on these two datasets are consistent.

The main results of our estimations are the following. First, the income channel takes precedence over the substitution channel in the long term: increased productivity (or wages) reduces the labour supply through shorter hours worked, the long-term elasticity being about -0.1 to -0.2 depending on the sub-period and the dataset considered. Second, the substitution channel may dominate in the short term but only on certain sub-periods and sets of countries. Third, concerning the impact of hours worked on productivity, the fatigue channel outweighs the fixed-cost channel: a reduction in hours worked raises productivity (or wages per hour). The elasticity estimates range from approximately -0.4 to -0.6, depending on the sub-period and the dataset considered.

These results are consistent with the previous literature, and reconcile short-term and long-term relations between productivity and hours worked.

What could be the future long-term evolution of worked hours?

What might be the impact of a productivity revival brought about by the digital revolution and by artificial intelligence on worked hours?

To give some order of magnitude, we postulate a simplistic scenario wherein the technological revolution yields a comparable impact on productivity to that observed during the preceding revolution in the US spanning from 1900 to 1975. Over this period, the average growth rate of labour productivity per hour stood at approximately 2.6%.

Drawing upon estimation results from Cette et al. (2023), hours worked could decrease, during the next three-quarters of the century, by about 0.45% per year, meaning that, In the US, starting at about 1,840 hours in the current period, by the end of the century hours worked per worker could average about 1,335 hours per year. This averages out at about 25 hours per week. The relationship between hours worked and productivity being circular, part of the observed productivity growth could be explained by the decrease in hours worked: 0.17 percentage points per year. Of course, in a secular stagnation scenario with a stable productivity level, hours worked could on the contrary remain stable.

To conclude

Over the next three-quarters of the century, several types of headwinds will have to be financed by productivity gains. The three main headwinds are of course climate policies, ageing population, and the reduction of the public debt. This means that in all likelihood a big part of the future productivity gains will not finance the reduction of hours worked: productivity gains now have to finance the long-term sustainability of our current quality of life. And without substantial productivity gains in the future, we would perhaps have to consider the necessity of longer hours worked to face the main headwinds in front of us.

References

Aghion, P, P Askenazy, R Bourlès, G Cette and N Dromel (2009), “Education, market rigidities and growth”, Economics Letters (102): 62–65.

Astinova, D, R Duval, N-J Hansen, H W “Ben” Park, I Shibata and F Toscani (2024), “Why the reduction in European workers’ hours after the pandemic is here to stay”, VoxEU.org, 27 February.

Bergeaud, A, G Cette and R Lecat (2016), “Productivity Trends in Advanced Countries between 1890 and 2012”, Review of Income and Wealth 62(3): 420–444.

Bergeaud, A, G Cette and R Lecat (2017), “Future growth: Secular stagnation versus technological shock scenarios”, VoxEU.org, 4 September.

Bick, A, N Fuchs-Schündeln and D Lagakos (2018), “How Do Hours Worked Vary with Income? Cross-Country Evidence and Implications”, American Economic Review 108(1): 170–199.

Bick, A, A Blandin and R Rogerson (2022a), “Hours and wages”, The Quarterly Journal of Economics 137(3): 1901-1962.

Bick, A, D Lagakos, N Fuchs-Schündeln and H Tsujiyama (2022b), “Structural Change in Labor Supply and Cross-Country Differences in Hours Worked”, Journal of Monetary Economics 130: 68–85.

Boppart, T and P Krusell (2020), “Labor supply in the past, present, and future: a balanced-growth perspective”, Journal of Political Economy 128(1): 118-157.

Bourlès, R and G Cette (2007), “Trends in “structural” productivity levels in the major industrialized countries”, Economics Letters 95(1): 151–156.

Bourlès, R, G Cette and A Cozarenco (2012), “Employment and Productivity: Disentangling Employment Structure and Qualification Effects”, International Productivity Monitor 23: 44–54.

Cette, G, S Chang and M Konte (2011), “The decreasing returns on working time: An empirical analysis on panel country data”, Applied Economics Letters 18(17): 1677–1682.

Cette, G, S Drapala and J Lopez (2023), “The Circular Relationship Between Productivity and Hours Worked: A Long-Term Analysis”, Comparative Economic Studies 65(4): 650–664.

Del Rey, E, J Naval and J I Silva (2022), “Hours and wages: A bargaining approach”, Economics Letters 217.

Eden, M (2021), “Time Inseparable Labor Productivity and the Workweek”, Scandinavian Journal of Economics 123(3): 940–965.

Li, H (2022), “The Time-Varying Response of Hours Worked to a Productivity Shock”, Journal of Money, Credit and Banking, Forthcoming.

Pencavel, J (2015), “The productivity of working hours”, The Economic Journal 125(589): 2052–2076.

Reif, M, F Tesfaselassie Mewael and M H Wolters (2021), “Technological Growth and Hours in the Long Run: Theory and Evidence”, Economica 88(352): 1016–1053.