Central banks have responded to the recent surge in inflation with restrictive policies. For many, the abrupt shift to rate tightening left little time to shrink their balance sheets, which had grown massively since the Global Crisis. Since most advanced economy central banks pay interest rates on bank reserves, the mismatch between a low return on assets and a rising cost of liabilities has triggered financial concerns. For example, the central banks of England, Switzerland, the US, Canada, and Australia have all recently reported losses. Central banks in the Eurosystem are also at risk and Germany’s federal audit office has warned in June 2023 that the Bundesbank may need a recapitalisation with budgetary funds.

Financial troubles may create significant challenges for the public image of central banks. The financial press has stoked fears about the consequences of these losses, with headlines such as “Decade of central bank largesse haunts taxpayers as losses loom” or ”Fallen heroes: Central banks face credibility crisis as losses pile up”.

These bold proclamations stand in contrast to the dominant view among economists, mainly that central bank losses and negative equity have no direct effect on their ability to operate effectively as long as money creation is not used to offset losses (Reis 2013, Archer and Moser-Boehm 2013, Allen et al. 2020, Goncharov et al. 2021).

A recent paper published by the Bank for International Settlements (Bell et al. 2023) argues that a central bank can “mitigate the risk of misperception through effective communication to their stakeholders” by explaining why losses occur and emphasising that they are unlikely to compromise the central banks’ ability to meet their objectives.

To communicate effectively in the present environment, central banks need to understand why losses occur, how previous episodes of losses have been managed, and if they posed a threat to central bank credibility and independence.

To provide a new perspective on these issues, in new research (Humann et al. 2023) we examine ten advanced economy central banks in the 1970s and 1980s to see how they coped with a period characterised by the greatest volatility in exchange rates and interest rates since WWII. The most recent and comprehensive analysis of central bank losses uses data starting the early 1990s (Goncharov et al. 2021).

Our study highlights two findings for advanced economy central banks. First, central bank profits actually increased with the anti-inflationary measures of the 1980s. We show that the profits of central bank depend on their policy instruments as well as their balance sheet position when rate tightening begins, rather than on the tightening per se. It turns out that legacy matters.

Unlike today, central banks in the 1980s avoided losses because they did not remunerate bank reserves and their balance sheets did not carry the legacy of a decade of large asset purchases at low interest rates and long maturity. Our counterfactuals show that only a combination of these factors could have triggered losses in the 1980s: none of them is sufficient on its own. Second, we show that some central banks suffered losses in the 1970s, before the Volcker shock, due to a depreciation of their foreign exchange reserves. In Switzerland and Germany, these transitory losses were carried forward and did not result in a transfer from the government. There is no evidence that these losses threatened the independence of central banks and their ability to fight inflation.

The stronger financial strength of the 1980s and its mechanisms

Central bank losses typically arise for three reasons. First, losses on domestic assets can be due either to the sale of securities at prices below their acquisition (book) value or to default of borrowers in the case of uncollateralised loans. Domestic assets of central banks are recorded at book value so that changes in the prices of these assets do not generate losses. Second, revaluations of foreign exchange holdings can generate losses, when the domestic currency appreciates against assets denominated in reserve currencies. Third, if the overall remuneration of the asset portfolio is less than the cost of liabilities, this can result in a loss.

The Volcker shock that began in October 1979 could have potentially resulted in losses for the US Federal Reserve and other central banks that followed suit by increasing their interest rates. However, these are not the outcomes we observe in our new data set on profits, losses, and balance sheet items for ten central banks from 1970 to 1990.

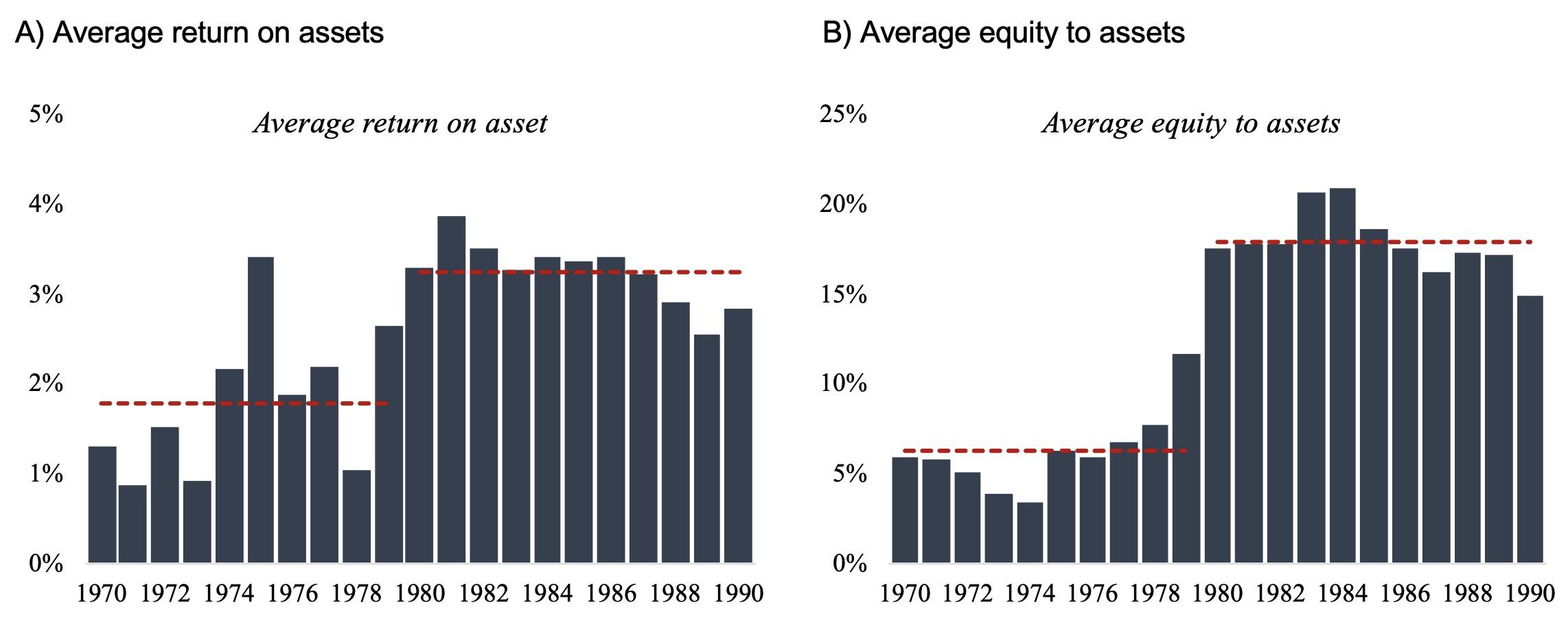

As Figure 1 shows, the average return on assets (ROA) increased from 1.9% in the 1970s to 3.4% in the 1980s.

An alternative measure of a central bank’s financial position, equity to total assets, rose from 6.2% in the 1970s to 17.8% in the 1980s. Both indicators increased strongly starting 1979 and reach their peaks in 1982-1984, a period corresponding to the disinflation policies of Western central banks. It is worth mentioning that the disinflation policies were carried out without decreasing nominal balance sheets in any of the ten central banks. Profits transferred from central banks to governments thus increased from 0.15% of GDP on average in 1970-1979 to 0.22% in 1980-1990.

Figure 1 The financial position of advanced economy central banks, 1970-1990

Notes: The return on asset (ROA) levels are computed as the average over the ten central banks of the sample. The red dashed lines correspond to the decades’ averages.

Source: Annual Reports, Authors’ calculations.

Why didn’t the disinflationary policies of the 1980s weaken the finances of central banks? First, revenues from lending operations increased with the higher lending rates while total assets did not decrease. Second, on the liability side, central banks did not remunerate bank reserves.

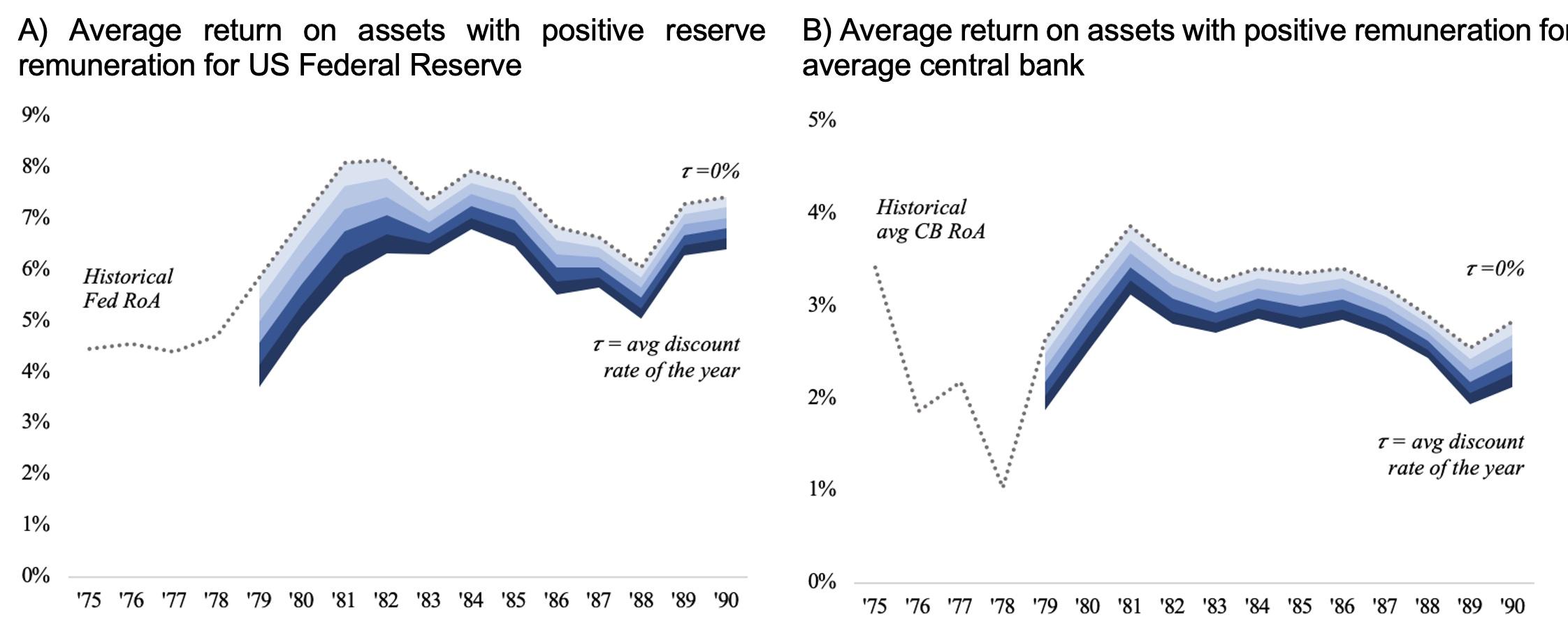

What if central banks in the 1980s had remunerated bank reserves? Figure 2 displays counterfactual simulations, which show that positive and high remuneration rates on reserves would have had only a limited effect on central bank return on assets. Moreover, doubling the share of reserves to total assets (to reach levels similar to today) would also not have generated losses. We thus run additional counterfactual simulations (reported in Humann et al. 2023) and evaluate scenarios that change parameters on the asset side, thus combining the three main features of today’s central banks: remuneration of reserves, large balance sheets, and assets previously purchased with long maturity and low interest rates. Our counterfactual scenarios can generate losses for the central banks of the 1980s only when we combine these three characteristics. None of them is sufficient on its own. Consequently, our counterfactuals also show that losses due to a mismatch between the returns on assets and liabilities are transitory: they are offset when assets purchased before the rate tightening mature and asset yields increase.

Figure 2 Counterfactual simulations

Notes: The dashed line corresponds to the observed return on asset (ROA) levels for the US Federal Reserve and the average central bank of the sample. Reserves up to the year’s average discount rate.

Source: Annual Reports, Authors’ calculations.

Managing the 1970s foreign exchange losses

In theory, central banks could have experienced large losses after the Volcker shock because of an appreciation of their currencies – similar to what Switzerland is presently experiencing. But that did not happen because US interest rates rose more rapidly than elsewhere. Thus, the US dollar appreciated strongly. The Fed held little foreign exchange whereas other central banks held dollars as their preferred reserve currency.

In the 1970s, before global rate tightening began, several European central banks experienced substantial losses on foreign exchange holdings. These losses were due to the two devaluations of the dollar in 1971 and 1973 and the subsequent dollar depreciation in the wake of the collapse of the Bretton Woods system. For example, losses at the German Bundesbank reached their peak in 1973, amounting to 5.3% of total assets. The German central bank carried forward its losses, covering them with future profits, without financial transfer from the government to the central bank. In 1978, the Swiss National Bank also experienced losses, amounting to 5.6% of total assets. These were also carried forward and cleared using future profits of the next two years.

In both these cases, losses were not seen as a constraint on the ability of the central bank to conduct countercyclical monetary policy. Germany and Switzerland were countries where average inflation was low and central bank independence was high (Bordo and Orphanides 2013).

Foreign exchange losses can be carried forward when the foreign exchange reserves are held by the central bank. By contrast, they are directly supported by the government when reserves are held through Exchange Stability Funds, which we illustrate with the case of foreign exchange losses in France in the 1970s. In countries that still have such a special fund (e.g. US, Canada, UK), the losses on foreign exchange would thus be borne by the Treasury.

Implications

Contrary to the already documented experience of the 1990-2000s (Bell et al. 2023), the cases of Switzerland and Germany in the 1970s illustrate that central bank losses were not restricted to emerging markets and small economies, and they are not incompatible with central bank independence. By contrast, there were no central bank losses due to disinflationary policies following the Volcker shock in the 1980s. Monetary policy could not be challenged on the grounds that it was costly for the taxpayer and resulted in a transfer to commercial banks. If current losses are not a threat to the financial stability of central banks, they could harm central bank independence and legitimacy in the absence of effective justification, especially in times of limited fiscal space and when reserve remuneration is perceived as a profit transfer to banks (De Grauwe and Ji 2023). Our historical studies reveal that central bank losses are not a consequence of disinflation policies per se, but result from the combination of policy instruments and the legacy of previous years of monetary policy on the balance sheet. To convince the public that their financial losses are not illegitimate, central banks have no choice but to justify their current operating framework and past monetary policy decisions.

References

Allen, J, W Bateman, S Gleeson, M Kumhof, R Lastra and S Omarova (2020), “Central Bank Money: Liability, Asset, or Equity of the Nation?”, CEPR Discussion Paper 15521.

Archer, D and P Moser-Boehm (2013), “Central Bank Finances”, BIS Papers No 71.

Bell, S, M Chui, T Gomes, P Moser-Boehm and A Pierres Tejada (2023), “Why are central banks reporting losses? Does it matter?”, BIS Bulletin 68, 07 February.

Bordo, M D and A Orphanides (2013), The great inflation: The rebirth of modern central banking, University of Chicago Press.

De Grauwe, P and Y Ji (2023), “Monetary Policies that Do Not Subsidise Banks”, VoxEU.org, 9 January.

Goncharov, I, V Ioannidou and M C Schmalz (2021), “(Why) do central banks care about their profits?”, Journal of Finance, forthcoming.

Humann, T, K Mitchener and E Monnet (2023), “Do Disinflation Policies Ravage Central Bank Finances?”, CEPR Discussion Paper 18246.

Mitchener, K and E Monnet (2023), “Connected Lending of Last Resort”, CEPR Discussion Paper 17831.

Reis, R (2013), “Central bank design”, Journal of Economic Perspectives 27(4): 17–44.