Following Russia’s unjustified full-scale invasion of Ukraine in 2022, 32 countries have supplied military assistance to Ukraine, with some dedicating almost 1% of their 2022 GDP. While military support for Ukraine is motivated primarily by international security and peace considerations, the fiscal expansion related to this war may have economic effects on the donating countries. In this column, we discuss early evidence on the recent fiscal multipliers in donor countries.

The idea of exploiting variation in military expenditures has long-standing support in economic research (e.g. Barro 1981, Hall 1986, Rotemberg and Woodford 1992, Nakamura and Steinsson 2014, Ramey and Zubairy 2018, Miyamoto et al. 2019, Auerbach et al. 2023). Much historical evidence indicates that the fiscal expansion driven by military spending is motivated primarily by geopolitical factors. The military support for Ukraine is a testament to this principle. Thus, by isolating the component of government spending that is independent of current and expected future economic conditions, it is possible to identify the output effects of government spending.

In our ongoing work (Chebanova et al. 2023), we estimate government spending multipliers for the period influenced by the war in Ukraine and the countries that provide military assistance to Ukraine. The government-spending multiplier measures the amount, in currency units, by which real GDP changes in response to a one currency unit increase in government spending. We find that, following the first Russian invasion of Ukraine in 2014, the government spending multiplier remained in line with the estimates obtained over longer historical periods. Moreover, the multiplier associated with military spending in 2022, a year that saw a dramatic rise in global geopolitical tensions, changed little relative to previous years. We also do not find significant differences between the multipliers for countries that provided military donations to Ukraine in 2022 and those for countries that did not.

How much military support was provided to Ukraine in 2022?

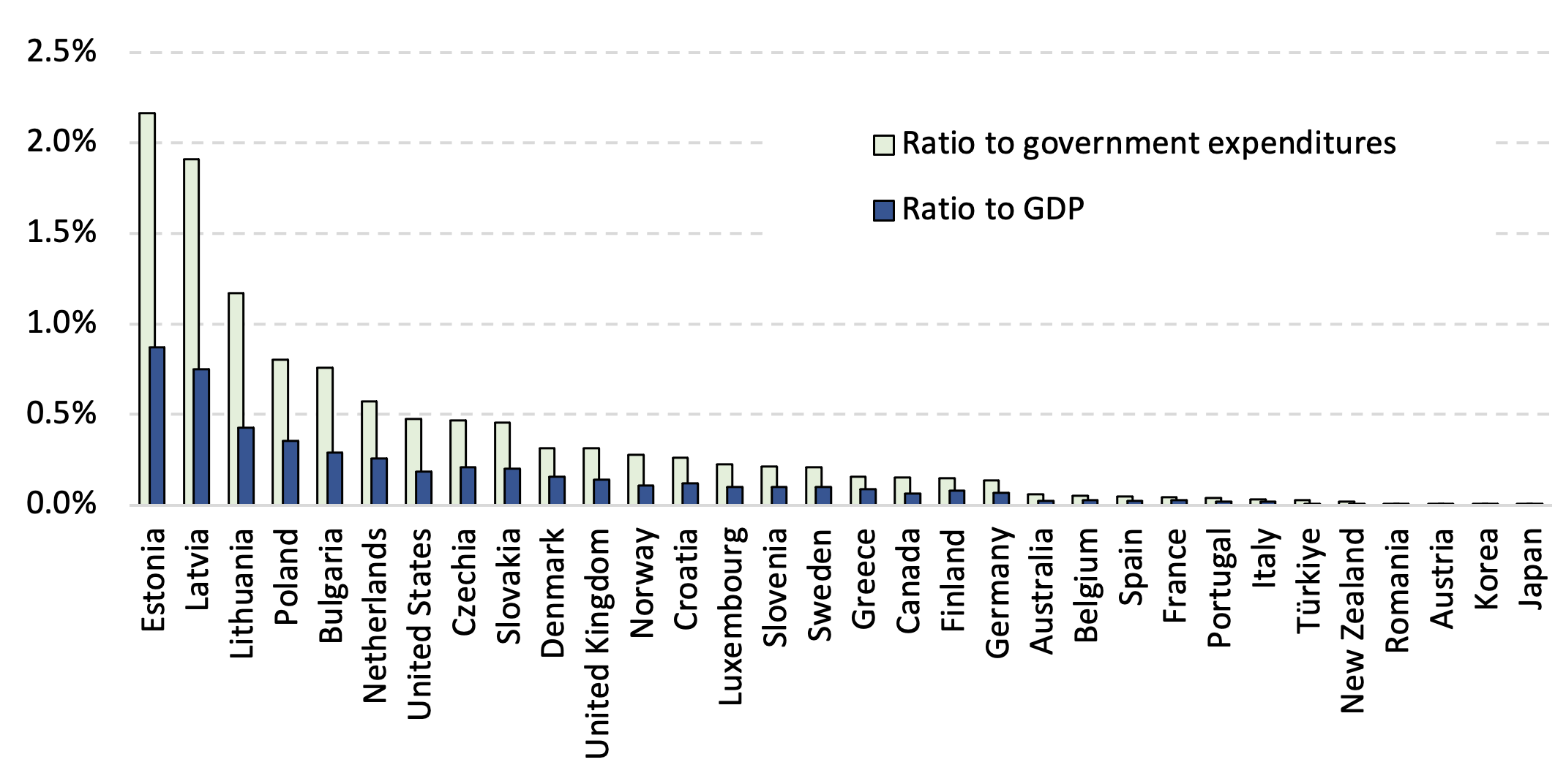

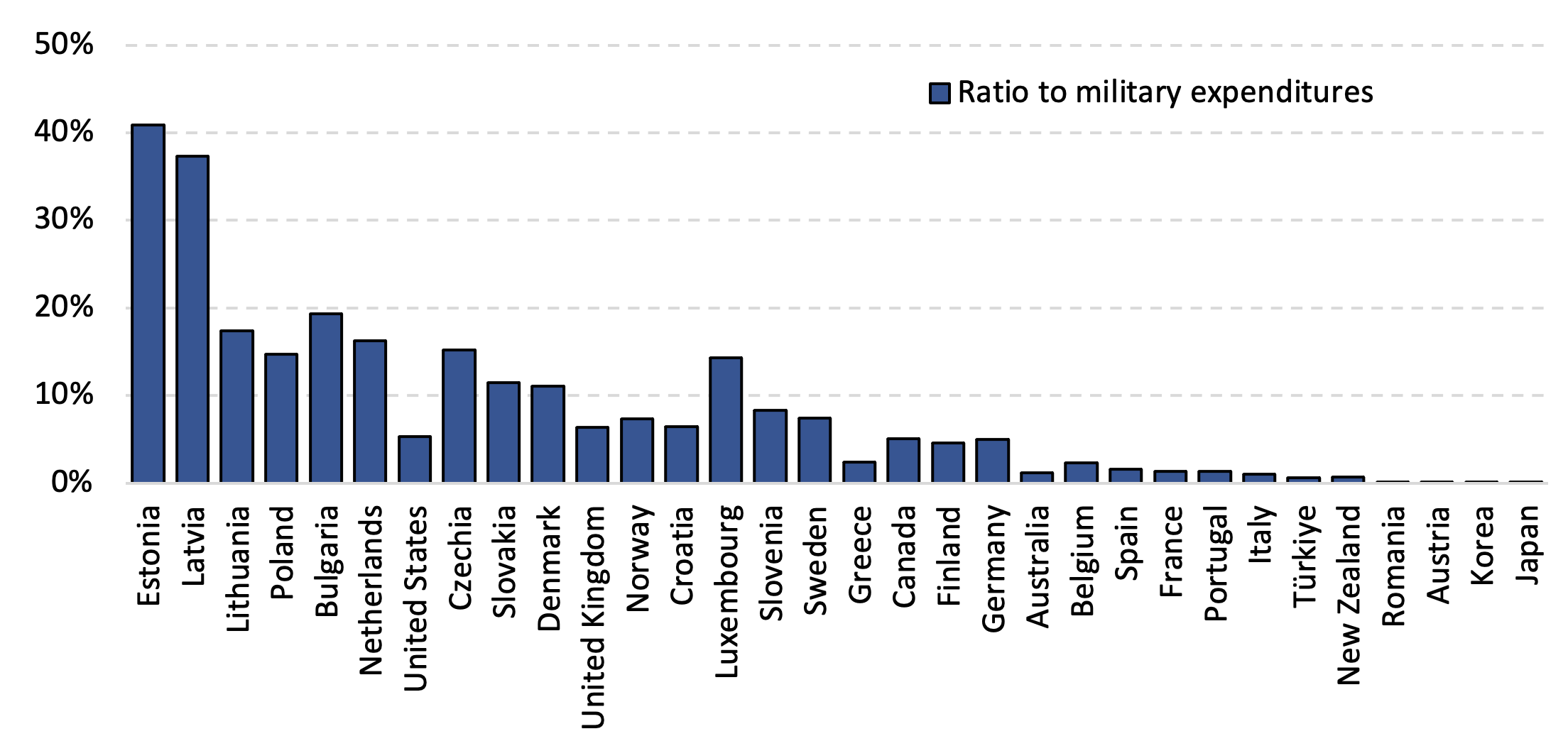

Prior to the full-scale invasion, military assistance to Ukraine was relatively small. The situation changed dramatically in February 2022. According to estimates by the Kiel Institute for the World Economy, total commitments of military aid to Ukraine over 2022 amounted to approximately $66.5 billion. This sum encompasses the cost of promised weapons, training, auxiliary services, and financing for the purchase of military goods. While this figure appears quite large in relation to Ukraine's economy and past assistance packages, it constitutes no more than 5% of the combined 2022 defence spending of donor countries. At the same time, there is significant heterogeneity across these countries in the amount of military assistance to Ukraine relative to their domestic production, total government expenditure, and defence budgets (Figures 1 and 2). Countries that perceive a more immediate threat from Russia have committed a significantly larger portion of their resources to support Ukraine.

Figure 1 Military support to Ukraine as a ratio to GDP and government expenditures

Source: Ukraine Support Tracker from Kiel Institute for the World Economy; IMF World Economic Outlook.

Figure 2 Military support to Ukraine as a ratio to military expenditures

Source: Ukraine Support Tracker from Kiel Institute for the World Economy; Military Expenditure Database from Stockholm International Peace Research Institute (SIPRI)

Fiscal multipliers and military assistance to Ukraine

We find that, for the sample of 101 countries during the 2006–2022 period, the government spending multipliers are in line with those for the earlier period. We reach this conclusion by following the estimation procedure in Sheremirov and Spirovska (2022), whose sample ends in 2013. Specifically, we employ local projections (Jordà 2005) and instrument total government consumption expenditures with military spending. We normalise real GDP, total government consumption, and military spending by country-specific trend GDP and control for country and time fixed effects as well as the lags of normalised real GDP, total government consumption, and military expenditures.

We estimate that a $1 increase in military spending by the countries that supported Ukraine in 2022 is associated with a $0.65 increase in output within a year and a $0.79–$0.87 increase over the following two years. The cumulative multipliers decline at longer horizons but remain positive and significant for five years.

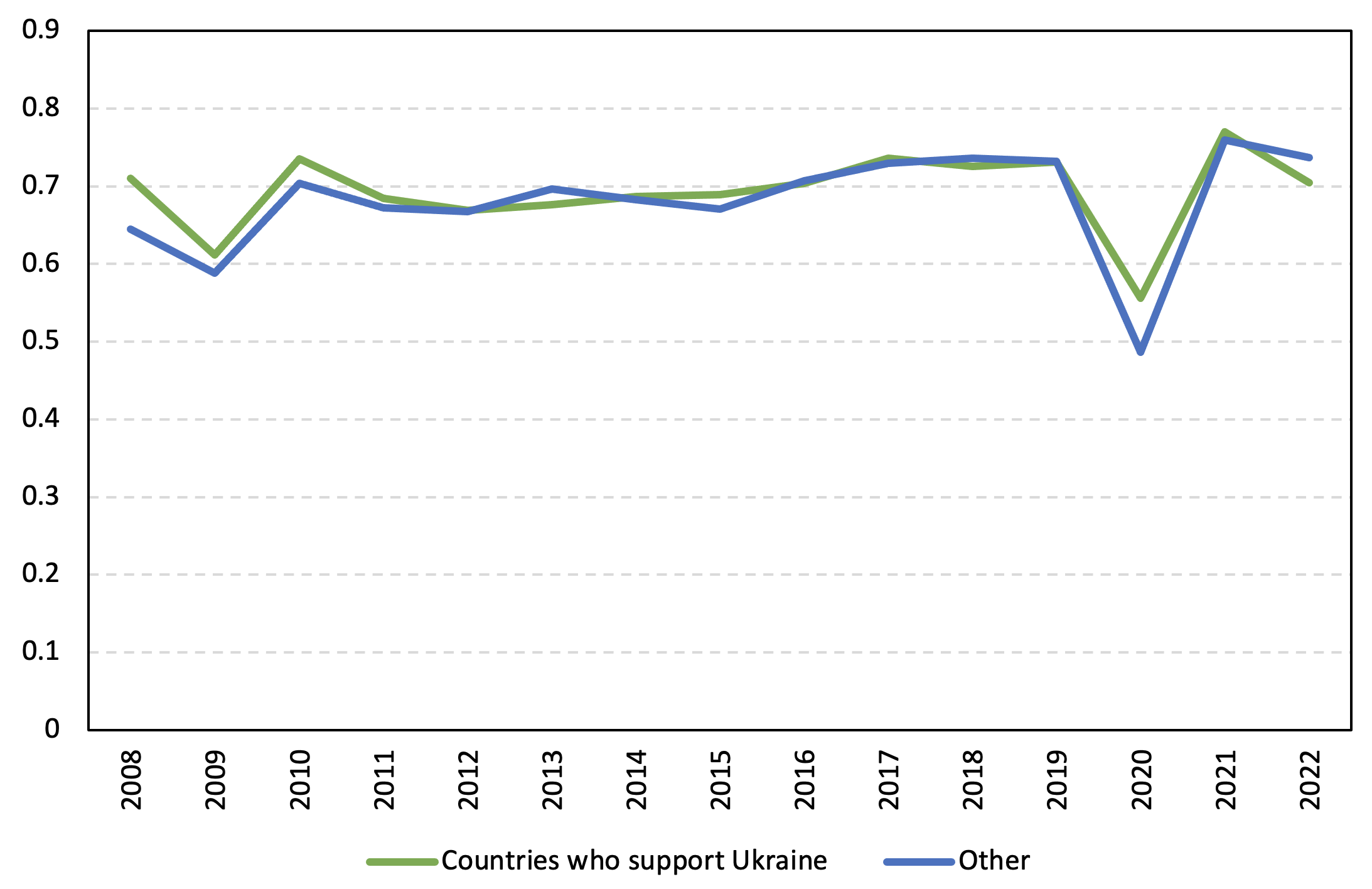

While the multipliers for donor countries are slightly larger than those for countries that provided no military assistance to Ukraine, the differences between the estimates for the two groups are small and not statistically significant at conventional levels. The multiplier appears to be remarkably stable over recent years, with the only noticeable dip occurring during the Covid-19 pandemic (Figure 3). Thus, it appears that the multiplier did not change materially following the first invasion of Ukraine in 2014 or in 2022.

Figure 3 On-impact government spending multiplier over time

Is this time going to be different?

Because fiscal expansion tends to have stronger output effects over longer horizons, and military support for Ukraine is ongoing, these early estimates will be reassessed as more data become available. There are, however, reasons to believe that they may indicate the lower bound for the output effects of military support for Ukraine.

One such reason is that in 2022 much of the military support provided to Ukraine took the form of transfers of existing military equipment and ammunition. As domestic production in donating economies ramps up over the next few years to replace that equipment, a rising proportion of military spending could be directed to durable capital goods. Furthermore, the effects of public spending on military research and development can spill over into other sectors (Moretti et al. 2023) and stimulate aggregate demand and aggregate supply simultaneously.

The government spending multiplier could be much larger in recessions than in expansions, because in recessions labour and capital are underutilised (Michaillat 2014). Some forecasters (e.g. IMF 2023) predict a slowdown in economic growth and more economic slack. If their predictions materialise, a stimulus to aggregate demand stemming from military support for Ukraine may come for many countries just at the right time.

Some of the fiscal expansion due to the recent rise in defence spending could be offset by fiscal consolidation elsewhere. But history teaches us that in most cases total government spending rises following the onset of an unexpected external war. Moreover, some influential studies (e.g. Auerbach and Gorodnichenko 2012) document that the government spending multipliers associated with military expenditures can be larger than the multipliers associated with other types of public spending. Thus, even if rising defence spending has a limited effect on total government spending, its effect on output could still be stimulative in the short term.

Finally, the means through which defence spending is financed can substantially affect the size of the multiplier. Recent analyses (Rathbone 2023) indicate that taxes typically change little in response to defence spending associated with short wars but tend to rise if a country needs to finance a prolonged war. While this suggests that the short-term stimulative effect of defence spending may eventually evaporate, defence spending could pay a ‘peace dividend’ in the long term through increased global cooperation and national security.

Conclusion

Following the full-scale Russian invasion of Ukraine in 2022, many countries provided substantial military assistance to help Ukraine defend its sovereignty and territorial integrity. The long-term geopolitical benefits from promoting global peace and security as well as the cost of assistance have been discussed widely following the invasion. Based on our ongoing research that focuses on estimating government spending multipliers, this column discusses an overlooked point: in the short term, an expansion of military spending due to the war in Ukraine may have a stimulative effect on output in donor countries. Our analysis implies that the economic cost of military assistance to Ukraine may be materially smaller relative to the case when this domestic output effect is ignored.

Authors’ note: The views expressed herein are those of the authors and do not indicate concurrence by the National Bank of Ukraine, the Federal Reserve Bank of Boston, the principals of the Board of Governors, or the Federal Reserve System.

References

Auerbach, A J, Y Gorodnichenko and D Murphy (2023), “Macroeconomic Frameworks: Reconciling Evidence and Model Predictions from Demand Shocks”, American Economic Journal: Macroeconomics, forthcoming (see also https://doi.org/10.3386/w26365)

Auerbach, A J and Y Gorodnichenko (2012), “Measuring the Output Responses to Fiscal Policy”, American Economic Journal: Economic Policy 4(2): 1–27.

Barro, R J (1981), “Output Effects of Government Purchases”, Journal of Political Economy 89(6): 1086–1121.

Chebanova, M, O Faryna and V Sheremirov (2023), “The Economic Effects of Military Support for Ukraine: Evidence from Fiscal Multipliers in Donor Countries”, unpublished manuscript.

Hall, R E (1986), “The Role of Consumption in Economic Fluctuations”, in R J Gordon (ed.), The American Business Cycle: Continuity and Change, University of Chicago Press, pp. 237–266.

IMF – International Monetary Fund (2023), World Economic Outlook: A Rocky Recovery, April 2023.

Jordà, O (2005), “Estimation and Inference of Impulse Responses by Local Projections”, American Economic Review 95(1): 161–182.

Michaillat, P (2014), “A Theory of Countercyclical Government Multiplier”, American Economic Journal: Macroeconomics 6(1): 190–217.

Miyamoto, W, T L Nguyen and V Sheremirov (2019), “The Effects of Government Spending on Real Exchange Rates: Evidence from Military Spending Panel Data”, Journal of International Economics 116: 144–157.

Moretti, E, C Steinwender and J Van Reenen (2023), “The Intellectual Spoils of War? Defense R&D, Productivity, and International Spillovers”, Review of Economics and Statistics, forthcoming.

Nakamura, E and J Steinsson (2014), “Fiscal Stimulus in a Monetary Union: Evidence from US Regions”, American Economic Review 104 (3): 753–792.

Ramey, V A and S Zubairy (2018), “Government Spending Multipliers in Good Times and In Bad: Evidence from US Historical Data”, Journal of Political Economy 126(2): 850–901.

Rathbone, J P (2023), “The Age-Old Question: How Do Governments Pay for Wars?”, Financial Times, 13 June.

Rotemberg, J J and M Woodford (1992), “Oligopolistic Pricing and the Effects of Aggregate Demand on Economic Activity”, Journal of Political Economy 100(6): 1153–1207.

Sheremirov, V and S Spirovska (2022), “Fiscal Multipliers in Advanced and Developing Countries: Evidence from Military Spending”, Journal of Public Economics 208: 104631.