Limiting global warming and the associated economic and social losses requires a drastic increase in investments in low-carbon infrastructures and technologies. Global annual investments in low-carbon energy alone will have to increase threefold by 2030 compared with the level in 2022 (IEA 2023). Private capital plays a pivotal role in furthering innovation and financing these investments to accelerate the diffusion of low-carbon technologies (Tomasi et al. 2022, Roukny et al. 2022). To this end, investors responsible for capital allocation decisions need clear policy signals (Berg et al. 2023) and the capacity to correctly assess firms’ exposure to the risks and opportunities that mitigation policies entail (i.e. transition risks) (Claessens et al. 2022, Pisu et al. 2022, Alessi et al. 2023). For example, mitigation policies might drive technological changes, accelerate the obsolescence of certain assets, and cause changes in demand, all of which affect firms based on their environmental and economic performance (i.e. their exposure to transition risks).

In a new paper (D'Arcangelo et al. 2023), we assess to what extent climate policies lead sophisticated investors (i.e. lenders in the syndicated loan market) to discriminate based on borrowers’ environmental performance and how this affects borrowers’ investment decisions. This study investigates how changes in the stringency of mitigation policies impact the spread of syndicated loans (i.e. the interest rate of syndicated loans minus a benchmark interest rate) of borrowers with good and bad environmental performance – measured by firms’ emission intensities, patents in climate change mitigation technologies, and environment, social and governance (ESG) scores. With regard to mitigation policies, the study focuses on the effects of both technology push (i.e. technology support policies) and market-pull (i.e. carbon pricing) policies.

A growing literature shows that financial markets incorporate information on firms’ environmental performance by adjusting the required rate of return. Investors increasingly require a premium when investing in firms with worse environmental performance as they ostensibly face higher transition risks (Kleimeier and Viehs 2016, Ehlers et al. 2022, Delis et al. 2019). The evidence suggests that this premium increased after the Paris Agreement (2015), underlining the importance of climate commitments and announcements in shaping expectations and capital allocation decisions (Delis et al. 2018, Seltzer et al. 2022, Mésonnier 2021). This paper looks specifically at the role of climate policies in this process by focussing on lenders operating in the syndicated loan market and the type of information they rely on to assess the transition risks borrowers face.

Stringent climate mitigation policies decrease the cost of debt of ‘green’ firms and increase that of ‘brown’ firms

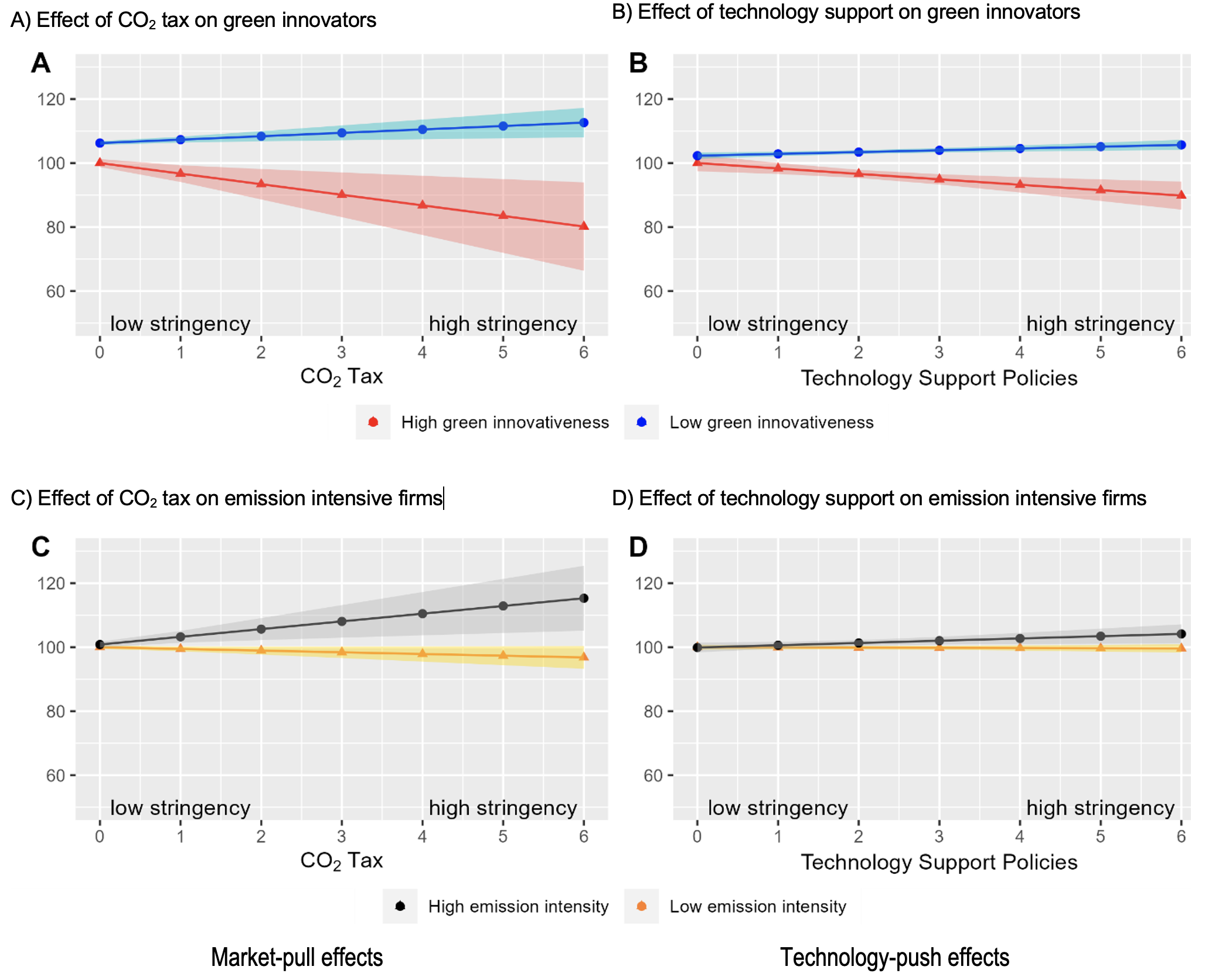

Our analysis shows that firms with good environmental performance (measured by low emission intensity or high patenting activity in climate change mitigation technologies) benefit from a lower cost of debt, as measured by syndicated loans spread. These effects can be large when market-pull policies (i.e. carbon taxes) and technology-push policies (i.e. green technology support) are stringent but disappear when they are not (Figure 1). For example, when carbon prices are above €50/t CO2, firms in the top 25% of mitigation technology patent’s distribution enjoy a loan spread that is 30% lower than firms in the bottom 25%. This is equivalent to €1.5 million less in yearly interest payments for the median syndicated loan deal (or 41 basis points lower loan spread). Overall, these results suggest that investors in syndicated loan markets price-in transition risks.

Figure 1 Effects of carbon taxes and technology support policies on syndicated loan spreads

Loan spreads (index = 100 for top 25% clean patenting firms, top 25% emission intensive firms, zero policy stringency)

Note: In each panel, the lines represent the predicted effect of a change in mitigation policy on two average firms that differ only by their environmental performance. Panel A and B show the linear predicted effects for firms among the top 25% and the bottom 25% of green innovators for different levels of the CO2 tax and technology support. Panel C and D show the linear predicted effects for higher emission intensive firms (top 25%) and low emission intensive firms (bottom 25%) at different levels of a CO2 tax and technology support. The shaded area represents confidence bands at 95% level.

Lenders operating in the syndicated loan market reward firms with good ESG scores irrespective of mitigation policies’ stringency, but they do not appear to rely on ESG scores to price transition risks. Results show that firms disclosing an ESG score benefit from lower syndicated loan spreads and this advantage increases with better scores. However, the effect of ESG scores on loan spreads is disconnected from the stringency of climate policy. This finding supports the view that ESG scores are weak proxies of firms’ actual environmental performance (Berg et al. 2022, OECD 2022a, Igan et al. 2021).

Climate policies generate winners and losers

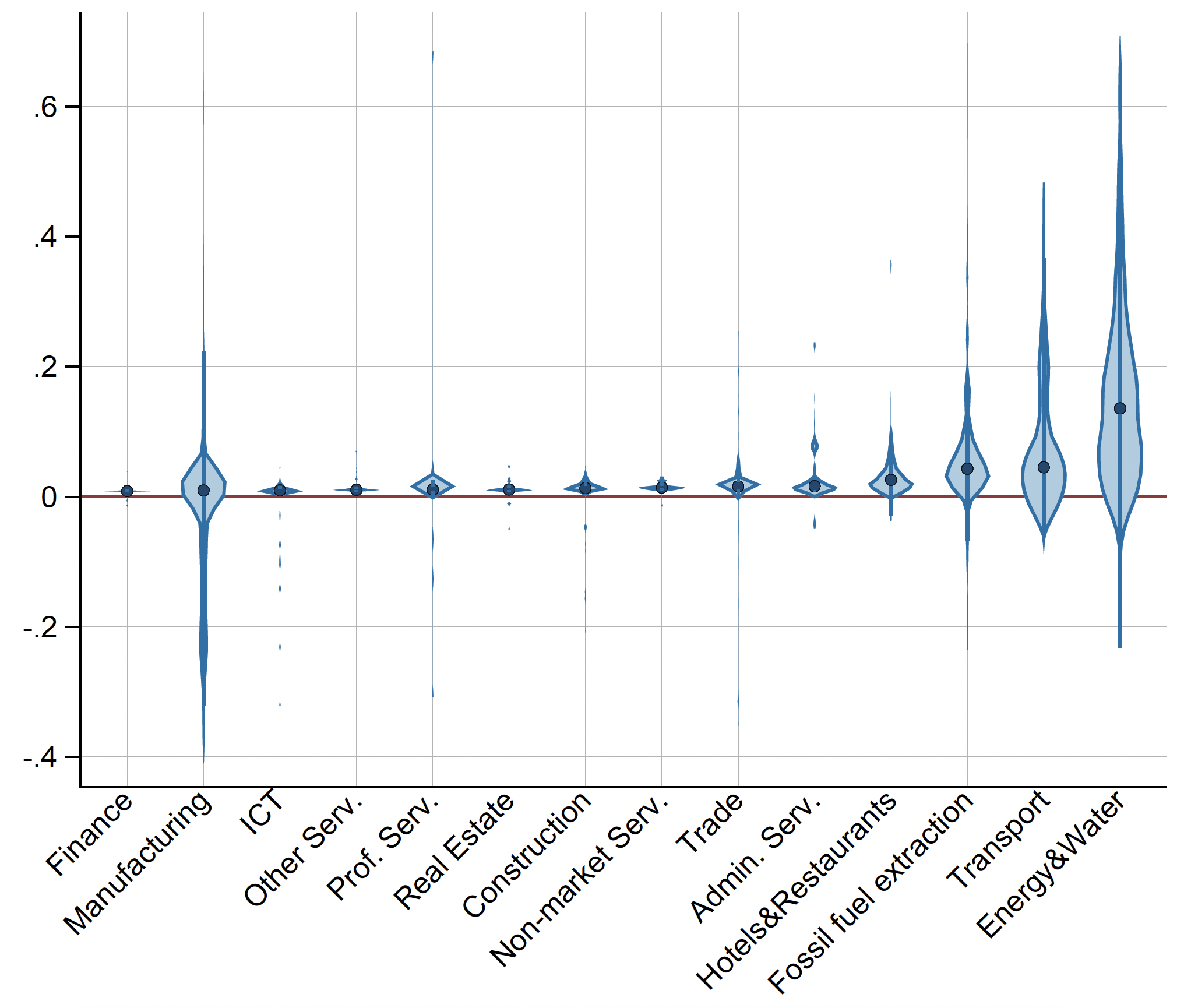

Rising stringency of climate policies will have heterogeneous effects across firms – both within and between sectors – depending on firms’ environmental performance. Using our main specification, results indicate that firms in the Manufacturing sector exhibit stark heterogeneity in environmental performance and thus in the predicted change in loan spreads. Some sectors, such as Energy and Water, and Transport, and Fossil fuel extraction, feature a large share of firms with relatively low environmental performance so that the median firm (in terms of its environmental performance) within the industry is expected (according to our estimates) to face higher loan spreads with stricter climate policies. However, even in these industries, there are firms with good environmental performance, which could benefit from higher carbon taxes though lower loan spreads. Most firms are predicted to experience an increase in loan spreads, as the median estimated impact in each industry (the dot in Figure 2) is above zero.

Figure 2 Effects of carbon taxes and technology support policies on syndicated loan spreads

Predicted percentage change on loan spreads

Note: The figure shows the distribution of percent predicted changes in loan spreads from increasing the carbon tax index by one unit (around €10/t CO2). The blue dots represent the median predicted change in firms’ loan spreads within each industry. Differences across and within industries are driven by the variation in deal- and firm-level characteristics (including environmental performance).Investors are increasingly incorporating environmental, social and governance (ESG) factors into asset allocation and risk decisions. However, ESG and Environmental pillar scores capture only imperfectly firms’ environmental performance and their exposure to climate policy-related risks. ESG scores can be unrelated to environmental performance, in terms of emission or green innovativeness, raising questions on the quality and usefulness of the information provided by ESG (OECD 2022a, 2022b). The analysis shows that sophisticated investors reward firms with good ESG scores irrespective of mitigation policies’ stringency, though they do not appear to rely on ESG scores to price transition risks. Firms disclosing an ESG score benefit from lower syndicated loan spreads and this advantage increases with better scores. However, the effect of ESG scores on loan spreads is disconnected from the stringency of climate policy. This finding supports the view that ESG scores are weak proxies of firms’ actual environmental performance (Berg et al. 2022, OECD 2022a, 2022b).

Mitigation policies might affect investment through the cost of debt. Simulations based on the empirical estimates indicate that a €10/tCO2 increase in CO2 taxes (equivalent to the average increase between 2002 and 2018 for countries that have a CO2 tax) raises investment by 12% for the top green innovators. It decreases investment by 11% for the top emitters. These effects are also economically significant for technology-push policies. Increasing technology support policy (in line with what observed in the 2002-18 period) is associated with a 5.2% increase in investment for the top green innovators and a 2.7% decline in investment for the top emitters.

Aligning private capital with the net-zero transition needs better and more widespread data on firms’ environmental performance

Our results show that strengthening mitigation policies can reduce the cost of debt of green innovators. Both market-pull and technology-push policies have large positive effects on green innovators, reducing their syndicated loan spreads substantially. This suggests that investors operating in the syndicated loan market assess transition risks based on mitigation policies’ stringency and firms’ actual environmental performances. However, assessing and pricing firms’ transition risks is likely to require detailed firm-specific information and the capacity to analyse such information that only large and sophisticated investors (as those considered in this analysis) can afford. Relying on ESG and the Environmental pillar scores is not a viable substitute, as such scores do not yet provide sufficient information to assess firms’ transition risks.

Policy intervention should then aim at reducing information asymmetries to enable smaller and less sophisticated investors than those considered in this analysis to assess and manage transition risks. This would help to allocate a larger share of capital in line with countries’ emission-reduction targets and the policies that go with them.

One option involves introducing new and more stringent environmental disclosure requirements and extending the coverage of existing ones. Adopting mandatory emission reporting and extending the scope of existing requirements should be a priority in many countries. Encouraging data comparability both between and within standards and requiring third-party verification by an accredited auditor would improve the usefulness and credibility of emission data.

Second, access to better data and improvements in the transparency of methodologies would contribute to enhance the quality and credibility of ESG ratings. Further guidance in assessing different metric categories would bolster comparability. Reducing the number of subjective judgements entering the ESG or Environmental pillar scores and publishing methodologies would support transparency and objectivity.

Finally, encouraging firms to produce climate risk assessments and transition plans, as well as subjecting them to third-party verification can further provide investors with useful and material information on firms’ plan to cope with the risks and opportunities arising from mitigation policies (OECD 2022a, OECD 2022b). Reinforcing and continuously updating investment principles established by international organisations, such as the United Nations Principles for Responsible Investments (UN-PRI), can provide investors with a shared and credible set of criteria to guide investment strategy. Several networks and initiatives aim to improve corporate reporting beyond ESG.

References

Alessi, L, E F Di Girolamo, M P Giudici and A Pagano (2023), "Banks’ exposures to high-carbon assets may represent a medium-term vulnerability for the financial system", VoxEU.org, 22 January.

Berg, F, J Kölbel and R Rigobon (2022), "Aggregate Confusion: The Divergence of ESG Ratings", Review of Finance 26(6): 1315-1344.

Berg, T, E Carletti, S Claessens, J-P Krahnen, I Monasterolo and M Pagano (2023), "Climate regulation and financial risk: The challenge of policy uncertainty", VoxEU.org, 10 May.

Claessens, S, N Tarashev and C Borio (2022), "Finance and climate change risk: Managing expectations", VoxEU.org, 7 June.

D'Arcangelo, F M, T Kruse, M Pisu and M Tomasi (2023), "Corporate cost of debt in the low-carbon transition: The effect of climate policies on firm financing and investment through the banking channel", OECD Economics Department Working Papers 1761.

Delis, M D, K de Greiff and S R G Ongena (2019), "Being Stranded with Fossil Fuel Reserves? Climate Policy Risk and the Pricing of Bank loans", SSRN Electronic Journal (Elsevier BV).

Delis, M, S Ongena and K de Greiff (2018), "The carbon bubble and the pricing of bank loans", VoxEU.org, 27 May.

Ehlers, T, F Packer and K de Greiff (2022), "The pricing of carbon risk in syndicated loans: Which risks are priced and why?", Journal of Banking and Finance 136: 106180.

IEA (2022), World Energy Investment 2022.

IEA (2023), World Energy Investment 2023, Paris.

Igan, I, D Kirti and D Elmalt (2021), "Limits to private climate change mitigation", VoxEU.org, 23 June.

Kleimeier, S and M Viehs (2016), "Carbon Disclosure, Emission Levels, and the Cost of Debt", SSRN Electronic Journal.

Mésonnier, J (2021), "Banks' climate commitments and credit to carbon-intensive industries: new evidence for France", Climate Policy 22 (3): 389-400.

OECD (2022a), "ESG ratings and climate transition: An assessment of the alignment of E pillar", OECD Business and Finance Policy Papers No. 06, OECD Publishing, Paris.

OECD (2022b), "Policy guidance on market practices to strengthen ESG investing and finance a climate transition", OECD Business and Finance Policy Papers No. 13, OECD Publishing, Paris.

Pisu, M, A Johansson, I Levin and F M D'Arcangelo (2022), "A framework to decarbonise the economy", VoxEU.org, 14 February.

Roukny, T, J Tielens and H Degryse (2022), "Asset overhang and the financing of climate change technology", VoxEU.org, 24 August.

Seltzer, L, L Starks and Q Zhu (2022), "Climate Regulatory Risk and Corporate Bonds", NBER Working Paper No 29994.

Tomasi, M, E Garcia-Appendini, G Barboni, M Cascarano and A Accetturo (2022), "Credit supply and green investment", VoxEU.org, 1 December.