Cultural differences between population groups are key to understanding many of society’s most pressing problems, such as the geopolitical stability of countries, the persistence of ethnic conflict across the globe, the growing political divide in the US, the breakdown of social consensus in many advanced democracies, and the disaffection of certain groups from the political process (Desmet and Wacziarg 2018). They also matter for trade, migration, and investment flows, as cultural similarity may lower informational asymmetries, increase trust, and facilitate integration (Kuchler et al. 2020, Bailey et al. 2020).

Despite its pivotal role, our ability to study cultural differences is severely limited by the availability of data. Because of the cost of collecting data, survey-based methods take a top-down approach, focusing on a select few salient measures deemed important by social scientists. Ethnographers, in contrast, favour observation, aiming to provide a more comprehensive description of culture. Neither method allows granularity – value surveys rarely cover more than a hundred population groups, whereas ethnographic studies tend to focus on one or just a few population groups. Measuring the culture of hundreds or thousands of population groups in its entire dimensionality requires a radically different approach.

An unintended consequence of social media

In a recent paper (Obradovich et al. 2020), we argue that massive online social networks that allow us to freely peer into the lives of billions of people might very well be the answer. For its more than two billion users worldwide, Facebook documents their everyday lives. It captures their activity not just on Facebook itself, but on all websites and apps where it has a presence. Additionally, by relying on GPS data, it also observes many dimensions of its users’ offline activity, such as whether they go to church, spend time in the outdoors, enjoy running, go to football games, or travel to specific places. Through their online and offline activity, users reveal their preferences and values, allowing Facebook to assign each one of its users a set of interests, ranging from their culinary tastes and favourite music, to their spiritual values and political position.

By providing quantitative, scalable, and high-resolution measures of revealed cultural preferences, Facebook has inadvertently created the world’s largest dataset for the measurement of culture. We compile publicly available data on nearly 60,000 interests across 225 countries via Facebook’s API. We then compute bilateral cultural distances between countries based on the shares of Facebook users that hold each one of these 60,000 interests. Similarly, we also compute distances between US states, California counties, and subnational regions across the globe.

Cultural distances across countries

To examine whether our Facebook measure of cultural distances mirrors common conceptions of cultural distances, Figure 1 shows a dendrogram for a subset of countries based on our novel measure. As can be seen, countries that are culturally or historically associated with one another – the US and Canada, India and Bangladesh, Germany and Austria – are placed directly next to one another. Not everything is driven by geography – Portugal is closer to Brazil than to the rest of Europe, the US is closer to New Zealand than to Mexico, and the UK is closer to Australia than to continental Europe. Overall, this dendrogram provides substantial validity to our measure of cultural distance.

Figure 1 Country dendrogram based on distances constructed from 60,000 Facebook interests

Going more granular

Cultural variation is not just relevant at the country level. Our methodology can in principle be applied to any population group: subnational regions, cities, age groups, gender groups, and so on. Using Facebook data at the subnational level, we employ network analysis to identify Germany’s and India’s relevant cultural divisions. As shown in Figure 2, we detect the East-West divide in Germany, and we identify three regional communities in India that correspond roughly to Indo-European, Dravidian, and Tibeto-Burman language families spoken in the country.

Figure 2 Regional divisions in Germany and India based on Facebook interests

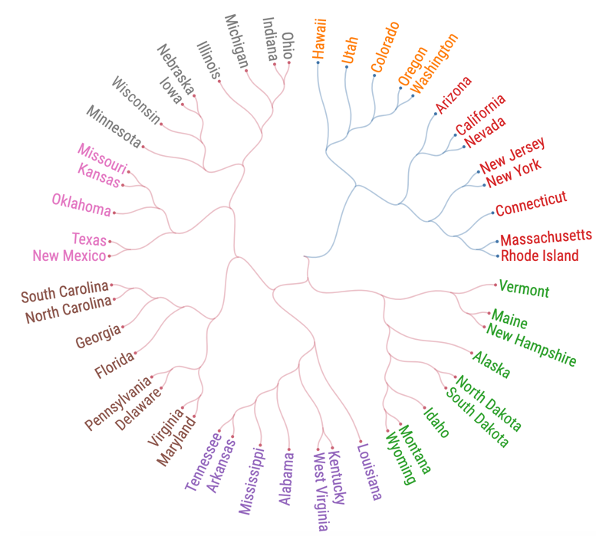

As another example, Figure 3 displays a dendrogram of the US states based on the bilateral distances constructed from Facebook interests. We see that states in the US Midwest are placed in proximity to one another, as are the states in the US South. Interestingly, mountainous and more rural states also cluster together, with Alaska being closest to states like North Dakota, Idaho, and New Hampshire, despite the substantial geographic distances between them. This supports the idea that the physical environment shapes cultural features.

We also examine how important national borders are in shaping culture. Is Paris closer to any other region in France, even the most rural ones, or is it more similar to other metro areas, such as Brussels or Madrid? We find that subregional cultural distances are almost always smaller within countries than across countries. In our sample we only find two examples of subnational regions closer to regions in another country than to any other region in their own nation: Flanders in Belgium and Donegal County in Ireland. Both exceptions can be traced back to fairly recent changes in country borders: the splitting of the province of Limburg between Belgium and the Netherlands in the 1830s and the Partition of Ireland in the 1920s. This suggests that national boundaries are key in shaping culture.

Figure 3 Dendrogram of US states based on distances constructed Facebook interests

How well does social media capture culture?

The clustering of countries, states, and regions conforms with our prior conception of cultural distances. But can we say something more about how well Facebook interests capture culture? An obvious test is to compare our measure of inter-country cultural distances to a wide variety of other measures. We find small positive correlations between our Facebook-based distances and measures of linguistic, geographic, religious, and genetic distances between country populations. When turning to direct measures of traditional notions of culture – provided via the World Values Survey (WVS) – we observe a more marked positive correspondence with a correlation coefficient of approximately 0.5.

Does this imperfect correspondence result from the measurement of additional dimensions of culture? At face value, our number of Facebook interests are several orders of magnitude larger than the number of questions in the WVS. When performing principal component analysis, we find that explaining 80% of the variance requires three times more principal components in the case of Facebook interests than in the case of WVS questions. This provides suggestive evidence that our Facebook measure covers a more comprehensive and diverse array of cultural dimensions than the WVS. To just give two examples, culinary preferences or sports feature prominently in people’s interests on Facebook but are absent from the WVS.

While our Facebook data span a wide variety of interests, do they also capture a broader set of specific cultural traits than those measured by the WVS? To explore this question, we employ a supervised machine learning algorithm that uses all our Facebook interests to predict close to 50 specific cultural attributes, ranging from generosity to kinship tightness, from uncertainty avoidance to son bias, and from beef consumption to contraceptive use. When comparing the predicted traits to the observed traits, we find an average correlation of 0.6, indicating that the wide array of Facebook data is also able to capture specific cultural traits.

Enormous potential for social scientists

There are many advantages to using social media data for the measurement of culture. By providing data on the revealed preferences of billions of humans, it provides us with comprehensive, scalable, cost-effective, high-resolution data for any population group. The increasing availability of massive data on culture and preferences promise nothing short of a revolution for social scientists.

References

Bailey, M, A Gupta, S Hillenbrand, T Kuchler, R J Richmond and J Stroebel (2020), “International Trade and Social Connectedness”, NBER Working Paper 26960

Desmet, K and R Wacziarg (2018), “The Cultural Divide”, CEPR Discussion Paper 12947.

Kuchler, T, Y Li, L Peng, J Stroebel and D Zhou (2020), “Social Proximity to Capital: Implications for Investors and Firms”, NBER Working Paper 27299.

Obradovich, N, Ö Özak, I Martín, I Ortuño-Ortín, E Awad, M Cebrián, R Cuevas, K Desmet, I Rahwan and A Cuevas (2020), “Expanding the Measurement of Culture with a Sample of Two Billion Humans”, CEPR Discussion Paper 15315.