The year 2022 was an extremely turbulent one for the euro. Analysts have described it as the "worst year in the euro’s history". The EUR/USD exchange rate was at $1.137 at the beginning of the year, but broke parity for the first time in 20 years in July, marking a 20-year low. It reached a year-to-date (YTD) low of $0.960 on 27 September, following the indefinite shutdown of the Nord Stream 1 pipeline that month. Following the ECB’s 75 basis-point policy hike on 27 October, the euro has recovered above parity, and the EUR/USD rate reached at $1.07 at the end of the year.

Figure 1 US dollar to euro spot exchange rate

While economies around the world have suffered the impact of an economic slowdown due to the pandemic and the Ukraine crisis, the effects of these events have been exacerbated across Europe this year. Three key factors have been identified as causing the depreciation of the euro in 2022:

- Europe’s heavy dependence on Russian energy and the associated economic slowdown brought about by the Ukraine invasion.

- The widening of the monetary policy gap between the Federal Reserve (Fed) and the ECB.

- The role of the US dollar as a ‘safe haven’ during times of financial and political uncertainty.

Russia’s invasion of Ukraine greatly weakened the global economy through disruptions in trade, and food and fuel price shocks, but these effects have been felt more strongly in Europe compared to the rest of the world. In its Autumn 2022 Economic Forecast, the European Commission predicted that most EU member states would enter into recession in the last quarter of the year due to high inflation, weak growth rates, and elevated uncertainty (European Commission 2022). The over-reliance of large European economies such as Germany and Italy on Russian gas has also resulted in energy-driven inflation being significantly higher in Europe than other economies, notably the US. Inflation in Europe reached 10.6% in October compared to just 7.2% in the US. Additionally, Bobasu and De Santis (2022) found that the Ukraine invasion and associated energy price increase has significantly increased uncertainty in the euro area, which negatively affected GDP and domestic demand in the euro area. With the energy crisis bringing the EU’s terms of trade to their lowest level in its history, the euro’s depreciation relative to the dollar was an inevitable consequence of the Ukraine invasion.

Some economists have also argued that the impact of the Chinese economic slowdown has hit Europe more than the US, leading to a weaker euro. Daniel Lacalle argues that the Chinese slowdown was also putting downward pressure on the euro area’s trade surplus, and consequently, the euro could no longer maintain its strength relative to the dollar.

Another driver of the euro’s depreciation is the relatively passive approach taken by the ECB to tackle inflation compared to the Fed. The Fed adopted a more hawkish stance towards rising inflation, sending clear signals in June 2021 that it would increase interest rates to rein inflation under control. It increased interest rates in March 2022, which was followed by further, faster hikes. In contrast, the ECB defended its loose monetary policy until July 2022, when it increased interest rates for the first time. This ‘shallower’ path adopted by the ECB for their policy rates led to a widening of the interest rate differentials between the two economies, leading investors to flock from European to American assets. As a result, since the Fed’s first announcement in June 2021 that it might raise rates, the dollar has appreciated by roughly 20% against the euro. Beckworth and Leeper (2022) have suggested that the ECB’s soft stance is influenced by the high debt levels of some euro area economies. See also von Hagen (1999) for a historical perspective.

Yet another reason for a weaker euro is the perception that the US dollar is a safe asset, particularly in crisis times. US assets, especially Treasury bonds, are generally viewed as a ‘safe haven’. Investors therefore prefer to hold these assets during times of turbulence and uncertainty. This usually leads to an increase in demand for these assets during crises, putting upward pressure on the dollar. The Ukraine crisis witnessed a similar trend, with the US dollar strengthening for three straight sessions in the wake of the Russian invasion. Egorov and Mukhin (2021) argue that as the issuer of the ‘dominant’ global currency, the US is more insulated from foreign spillovers, and can also extract rents in international goods and asset markets, thereby benefitting from its global status.

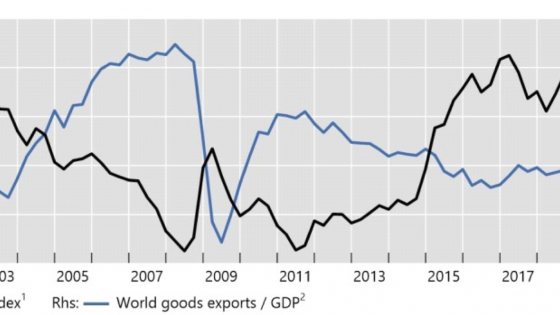

A weak currency could be a desirable side effect if its weakness is caused by developments in the real economy. Beck et al. (2022) found that during an exchange-rate depreciation, large banks with high net foreign currency asset exposure increase lending to export-intensive firms and small banks, and regions with such small banks experience higher output growth. Conventional economic theory also dictates that a weaker currency boosts exports. However, as Mauro et al. (2017) summarise, there is still widespread disagreement amongst economists regarding the sensitivity of exports to exchange rate fluctuations. Ahmed et al. (2015) argue that the emergence of global value chains has led to a sharp decline in the elasticity of manufacturing export volumes to the real effective exchange rate. Tsyrennikov et al. (2015) disagree, citing little evidence of a general disconnect in the relationship between exchange rates and exports and imports over time.

Some economists have argued that the weak euro has been an ineffective stabilisation factor in this crisis. With supply chain disruptions and sanctions looming in the background, European businesses have been unable to take advantage of their price competitiveness and profit from the lower real effective exchange rate (Colijn and Brzeski 2022). Additionally, with imports becoming more expensive, a weak euro significantly exacerbates inflationary pressures in the economy, compounding an already-grave problem.

There is much disagreement as to whether the ECB should take steps boost the euro or whether international coordination is desirable. Lodge and Perez (2021) found that due to globalisation effects, the exchange rate pass-through (ERPT) to inflation has declined in the EU to at around 0.3%, compared to 0.8% in 1999. As such, an intervention in the foreign exchange market by the ECB may be a step ‘too far’. On the other hand, almost half of all cross-border loans and international debt securities are denominated in US dollars. Economists argue that if the currencies like the euro were allowed to weaken relative to the dollar, it could make debt repayment extremely difficult for the private sector, increasing the risk of debt distress (Gopinath and Gourinchas 2022). However, Ethan Ilzetzki (London School of Economics) argues that high income economies like the EU are much more hedged against this type of risk, and that a strong dollar could actually improve the balance sheets of some institutions.

Some experts have also cited the additional inflationary pressures created by a weak euro as a justification for the ECB to intervene and strengthen the euro. There have been suggestions of implementing another version of the Plaza Accord – instituting an agreement amongst global economies to coordinate to weaken the dollar, thereby relatively strengthening other currencies like the euro.

In this month’s survey, members of the CfM-CEPR panel of experts on the European macroeconomy were asked for the causes of the euro’s weakness in 2022 and whether a policy response is merited if euro weakness should return.

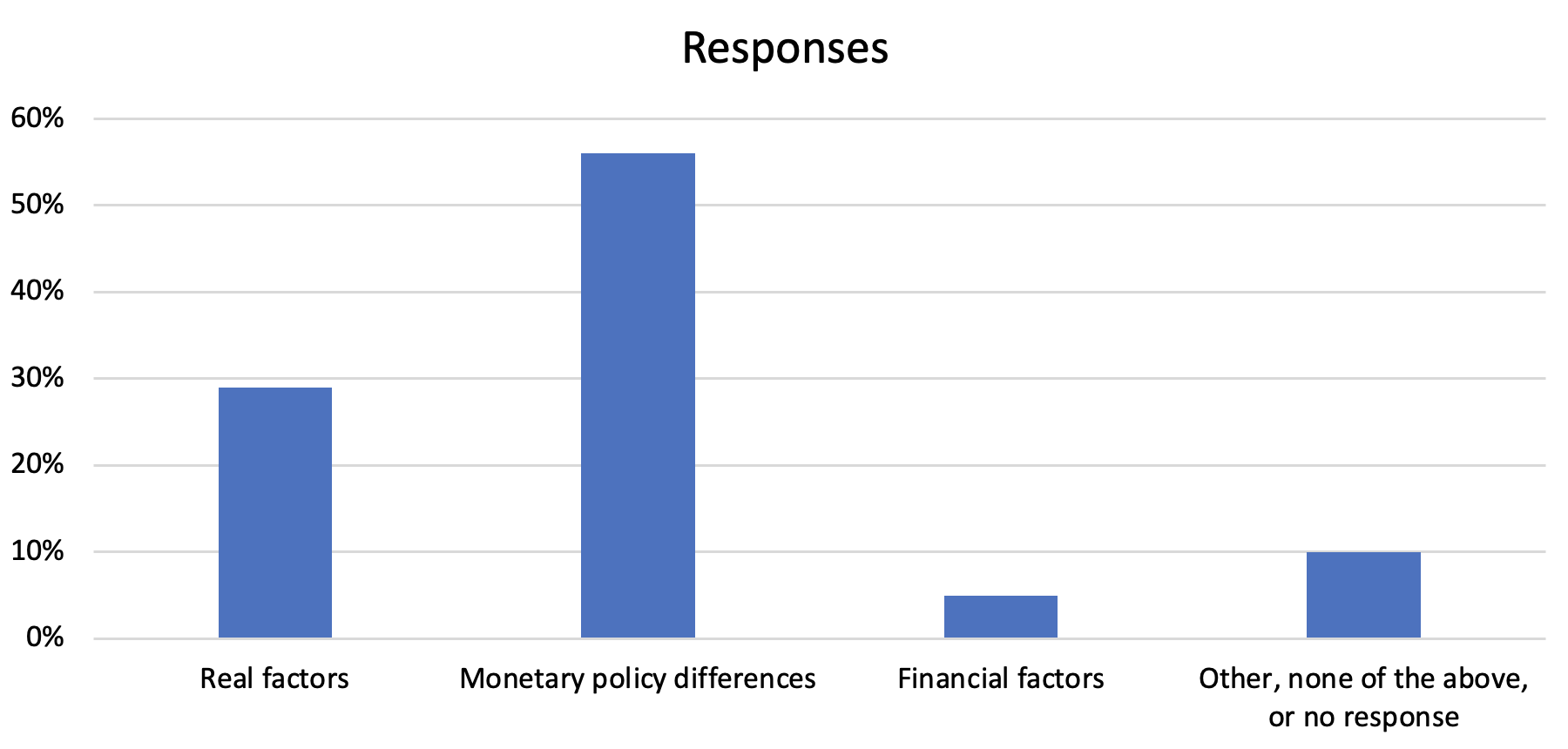

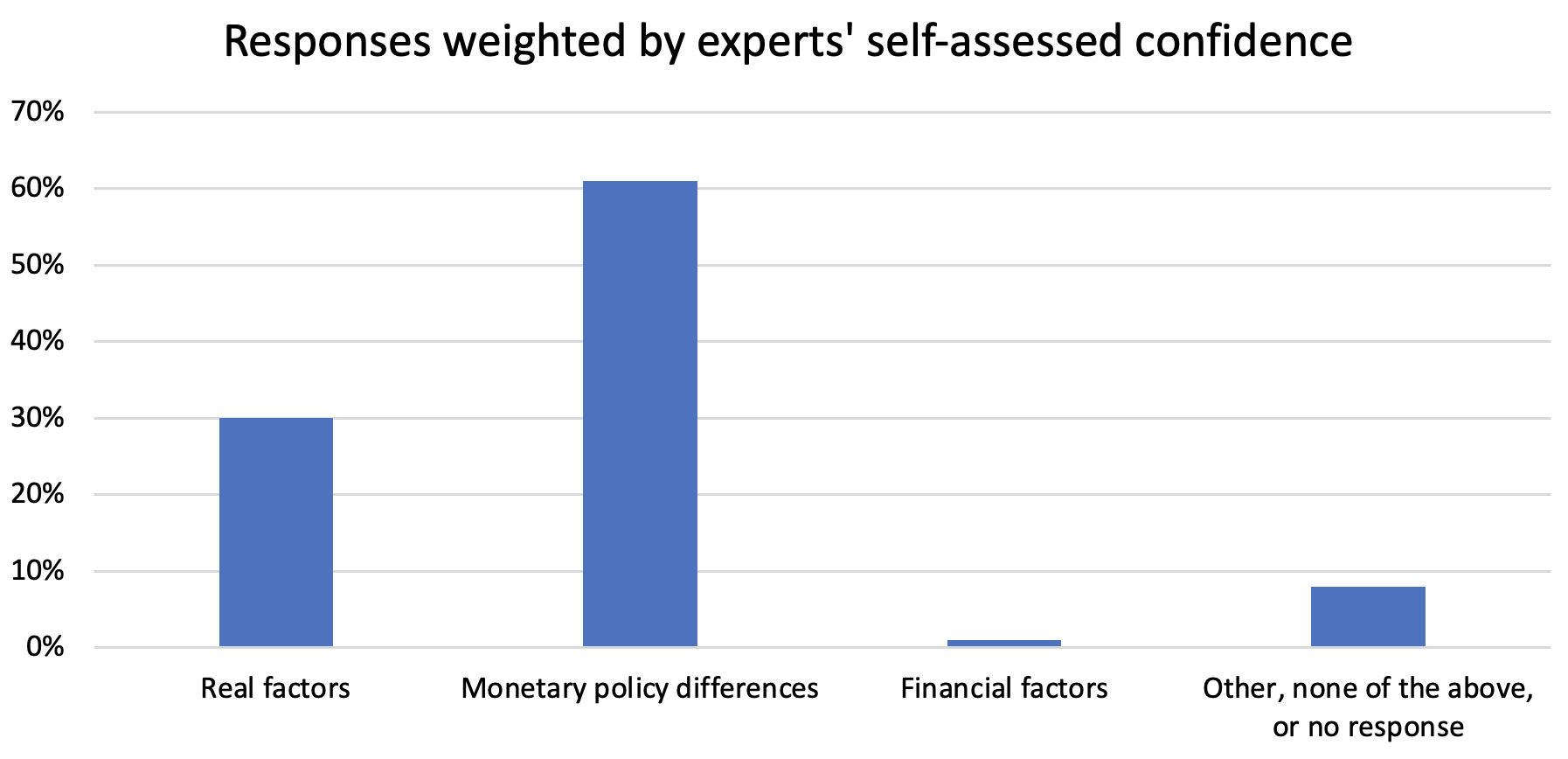

Question 1: What was the main cause for the euro’s decline relative to the US dollar in 2022?

Forty-one panel members responded to this question. A majority of 56% of the panellists think that monetary policy differentials were the main cause for the euro’s weakness in 2022. This majority strengthens slightly to 61% when weighing panellists’ responses by their self-assessed confidence levels. Twenty-nine percent of the panel attribute the euro’s decline to factors in the real economy.

Most panellists cite monetary policy differences between the euro area and the US as the primary cause behind the euro’s decline last year. Maria Demertzis (Bruegel) points out that “the real exchange rate [was not] different to historical values [in 2022]”, indicating that “real factors or indeed the war in Ukraine” could not be the driving factors for this phenomenon. Jagjit Chadha (National Institute of Economic and Social Research) provides a potential explanation for the ECB’s relatively dovish approach, claiming “a less aggressive response to emergent inflationary pressures and concerns about weak growth in the face of high levels of indebtedness may have acted to constrain the policy response.” Echoing these sentiments, Morten Ravn (University College London) highlights that “there were initial doubts about the ECB’s willingness to increase the policy rate in the face of ‘fragmentation risk’ and continuing credit policies.” However, as put by Fabrizio Coricelli (University of Siena and Paris School of Economics), “with the tightening in ECB policy in the second half of 2022, the euro has recovered some of the lost ground,” proving that monetary policy differences were the main reasons behind the depreciation of the euro.

Almost a third of the panel believes that real factors were responsible for the euro’s decline in 2022. Several panellists state the Russia-Ukraine war as a leading cause behind the depreciation. Omar Licandro (University of Nottingham) and Evi Pappa (European University Institute) claim that Europe’s “high energy dependence” on Russia – especially on “Russian fossil fuel imports” – has contributed significantly to the euro’s downturn. Jumana Saleheen (Vanguard Asset Management) provides another explanation, claiming that differences in growth expectations between the US and the euro area were behind the depreciation. She states that amid fears that “[a] lack of gas [due to the Ukraine invasion] would bring European industry to its knees”, the US experienced a “positive terms of trade shock”, which made it “richer”. Along with a “strong post-Covid recovery” and “monetary policy differentials”, this resulted in investors expecting the US to “grow much faster” than the euro area, leading to a stronger dollar. Lukasz Rachel (University College London) also shares the opinion that the US benefited from a “positive terms of trade shock”. However, he further states that “European economies dealt with energy disruptions better than expected”, and hence, “financial factors” may have played a key role in the euro’s decline – as suggested by Itskhoki and Mukhin (2022).

Paul de Grauwe (London School of Economics) offers an alternate view of the situation, warning that economists simply “did not know” why the euro-dollar rate moved in 2022. He warns against devising stories to justify the euro’s declining, stating “too many economists invent stories that appear to be plausible.”

We also asked Chat GPT this question. Here was its response: “I am sorry, my knowledge cut-off date is 2021, so I am unable to provide information on events that occurred after that date. However, there can be many factors that can cause a decline in the value of a currency, such as economic conditions, interest rate changes, political developments, or market sentiment.” The panel was reassured that it cannot (yet) be replaced by a computer.

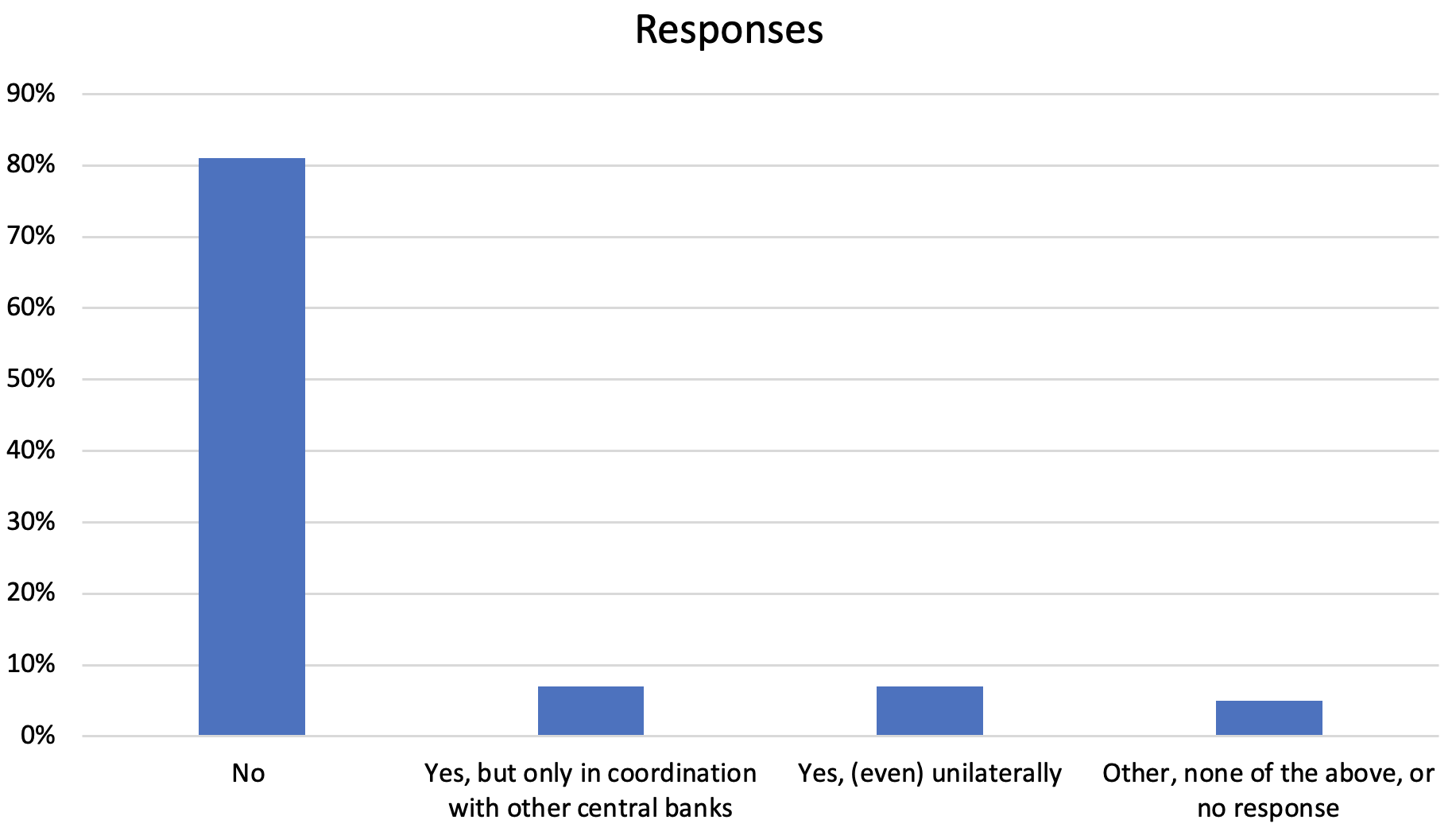

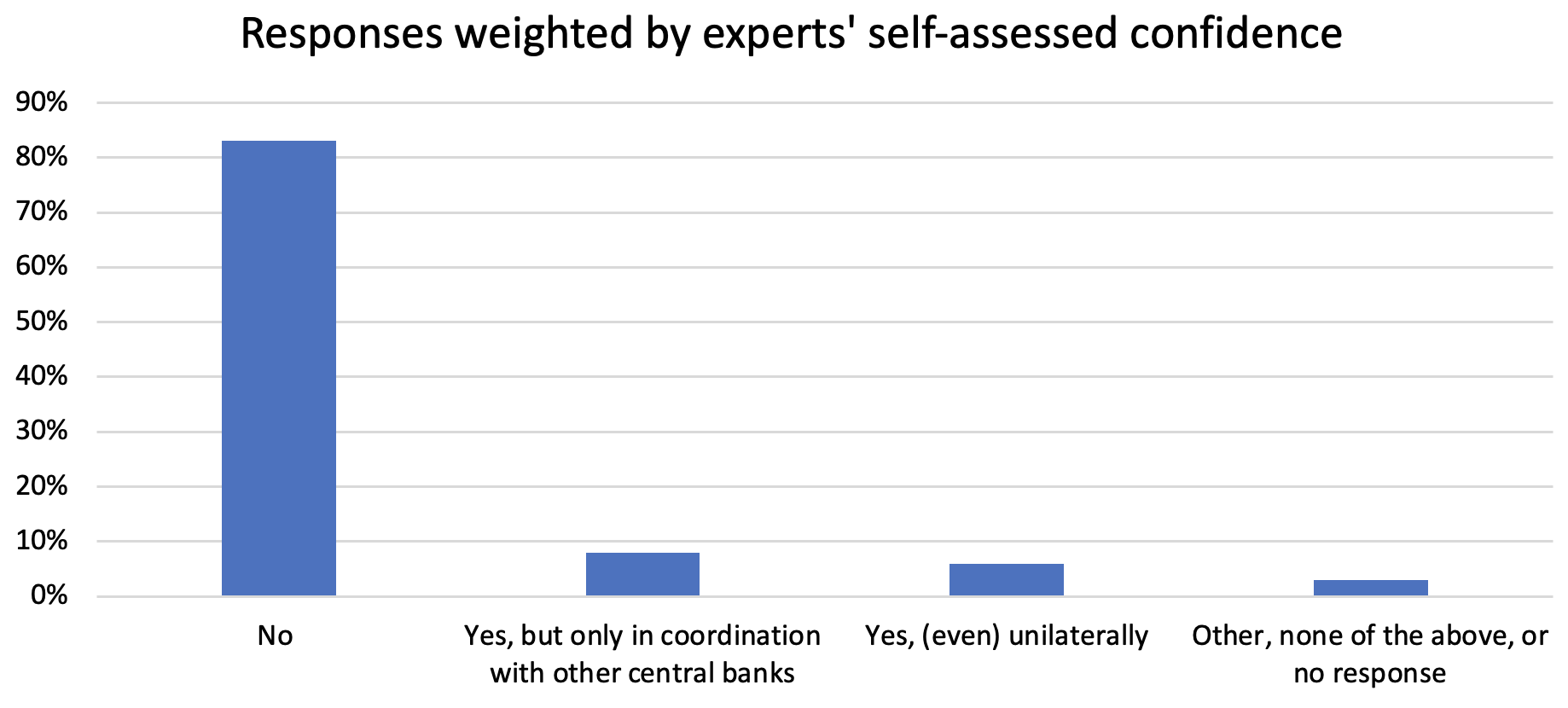

Question 2: Should the ECB respond to movements in the euro-dollar exchange rate of the nature observed in 2022?

Forty-one panel members answered this question. The vast majority (81% of the panel) think the ECB shouldn’t respond to exchange rate fluctuations of this sort. Fourteen percent of the panellists think the ECB should respond and these panellists were equally divided among those wanting to respond only in coordination with other countries and those willing to respond even unilaterally.

Most of the panel believed that the ECB’s focus should be on targeting inflation, not these exchange rate fluctuations. This view is summed up by Andrea Ferrero (University of Oxford): “The ECB should continue to focus on its inflation stability mandate and thus respond to exchange rate movements only insofar as inflation is affected.” Ethan Ilzetzki (London School of Economics) points out that as the “Eurozone economies were running large current account deficits”, the exchange rate simply did “what it was supposed to.” It forced European economies to “limit expensive energy imports or else finance it through greater exports or lower consumption of other imports.” Jürgen von Hagen (Universität Bonn) further claims that the ECB’s problem is not the exchange rate, but rather, its ability to “fend off political pressures from the member governments” and maintain its independence. Cédric Tille (The Graduate Institute, Geneva) echoed these sentiments, stating that the ECB should react to the exchange rate only “to the extent that the exchange rate connects to inflation” and that any response should be “an answer to price pressure, not the exchange rate itself.”

A small fraction of the panel supported ECB response to foreign exchange movements, either unilaterally or in coordination with other central banks. Richard Portes (London Business School and CEPR) expresses support for unilateral intervention by the ECB but argues that intervention would only be justified “insofar as exchange-rate depreciation might increase inflationary pressures or threaten financial stability.” Given that similar opinions were shared by panellists opposing intervention (such as Cédric Tille and Andrea Ferrero), most of the panel reached a consensus on when ECB intervention would be appropriate but disagreed whether current circumstances merited such intervention.

Jorge Braga de Macedo (Nova School of Business and Economics, Lisbon) also advocates ECB intervention, but stresses the need for coordination with other central banks. Citing historical reasons, he states: “Central bank coordination has been a feature of the international monetary system since the stagflation of the 1970s, and the creation of the euro has made it necessary especially when international political rivalries return, and war require NATO attention again. Unfortunately, it is not sufficient because of changes in patterns of international trade and investment and new security threats not seen since the 1970s.”

References

Ahmed, S, M Appendino and M Ruta (2015), “Depreciations without Exports? : Global Value Chains and the Exchange Rate Elasticity of Exports”, World Bank Policy Research Working Papers.

Beck, T, P Bednarek, D te Kaat and N von Westernhagen (2022), “The Real Effects of Exchange Rate Depreciation: The Role of Bank Loan Supply”, CEPR Discussion Paper 17231.

Beckworth, D and E Leeper (2022), “Eric Leeper on the Interactions of Fiscal and Monetary Policy | Mercatus Center”, podcast on www.mercatus.org, 4 April.

Bobasu, A and R De Santis, (2022), “The impact of the Russian invasion of Ukraine on euro area activity via the uncertainty channel”, ECB Economic Bulletin, Issue 4/2022.

Colijn, B and C Brzeski (2022), “Euro Weakness Is No Blessing in Disguise for the Eurozone”, ING Think, 17 August.

Egorov, K and D Mukhin (2021), “Policy implications of dollar pricing”, VoxEU.org, 19 November.

European Commission (2022), “Autumn 2022 Economic Forecast: The EU Economy at a Turning Point”, ec.europa.eu, 11 November.

Gopinath, G and P Gourinchas (2022), “How Countries Should Respond to the Strong Dollar”, IMF Blog, 14 October.

Itskhoki, O and D Mukhin (2022), “Sanctions and the Exchange Rate”, VoxEU.org, 16 May.

Lodge, D and J Perez (2021), “The implications of globalisation for the ECB monetary policy strategy”, Occasional Paper Series, No 263, ECB.

Mauro, F, J de Kerke and V Demian, (2017), “You need an ‘extra moment’ to assess the impact of the exchange rate”, VoxEU.org, 8 December.

Tsyrennikov, V, W Lian, M Poplawski-Ribeiro and D Leigh, (2015), “Exchange rates still matter for trade”, VoxEU.org, 30 October.

Von Hagen, J (1999), “A New Approach to Monetary Policy (1971-8)”, in Deutsche Bundesbank (ed.), Fifty Years of the Deutsche Mark. Central Bank and the Currency in Germany since 1948, New York: Oxford University Press, 1999.