Two empirical regularities appear puzzling at first glance: (1) a significant reduction in trade barriers worldwide (Baldwin 2016) following China’s admission to the WTO in December 2001; and (2) a significant increase in markups charged by the US firms (De Loecker et al. 2020). The latter appears to contradict the conventional wisdom that a reduction in trade barriers should result in increased domestic competition (Amiti et al. 2020), leading to lower markups. We provide an explanation for this apparently puzzling phenomenon. In recent paper (Chintha et al. (2024), we argue there are two forces at work when trade barriers come down, leading to increased globalisation of trade. First, increased domestic competition would make it difficult for US firms to increase their domestic profitability. Second, easier access to foreign markets would provide new opportunities for those US firms with significant intangible assets such as internationally recognised brands, technical know-how, etc., resulting in increased foreign profitability. We find that there are indeed two effects. While domestic profitability of US firms remained flat, foreign profitability increased, and the overall profitability increased due to the dominance of the latter effect.

A new regime with increased globalisation of trade

We use China's accession to the WTO in 2001 as heralding a new world regime with freer global trade. US international trade as a proportion of US GDP increased from an annual average of 20.3% during the pre-globalisation period of 1984-2002 to 27.4% during the post-globalisation period of 2003-2019.

We use the ratio of aggregate earnings before interest and taxes to aggregate sales (the earnings before interest and taxes, or EBIT, margin) as a measure of overall profitability of publicly traded US firms. We also find the results to be robust with respect to several other measures of profitability as well.

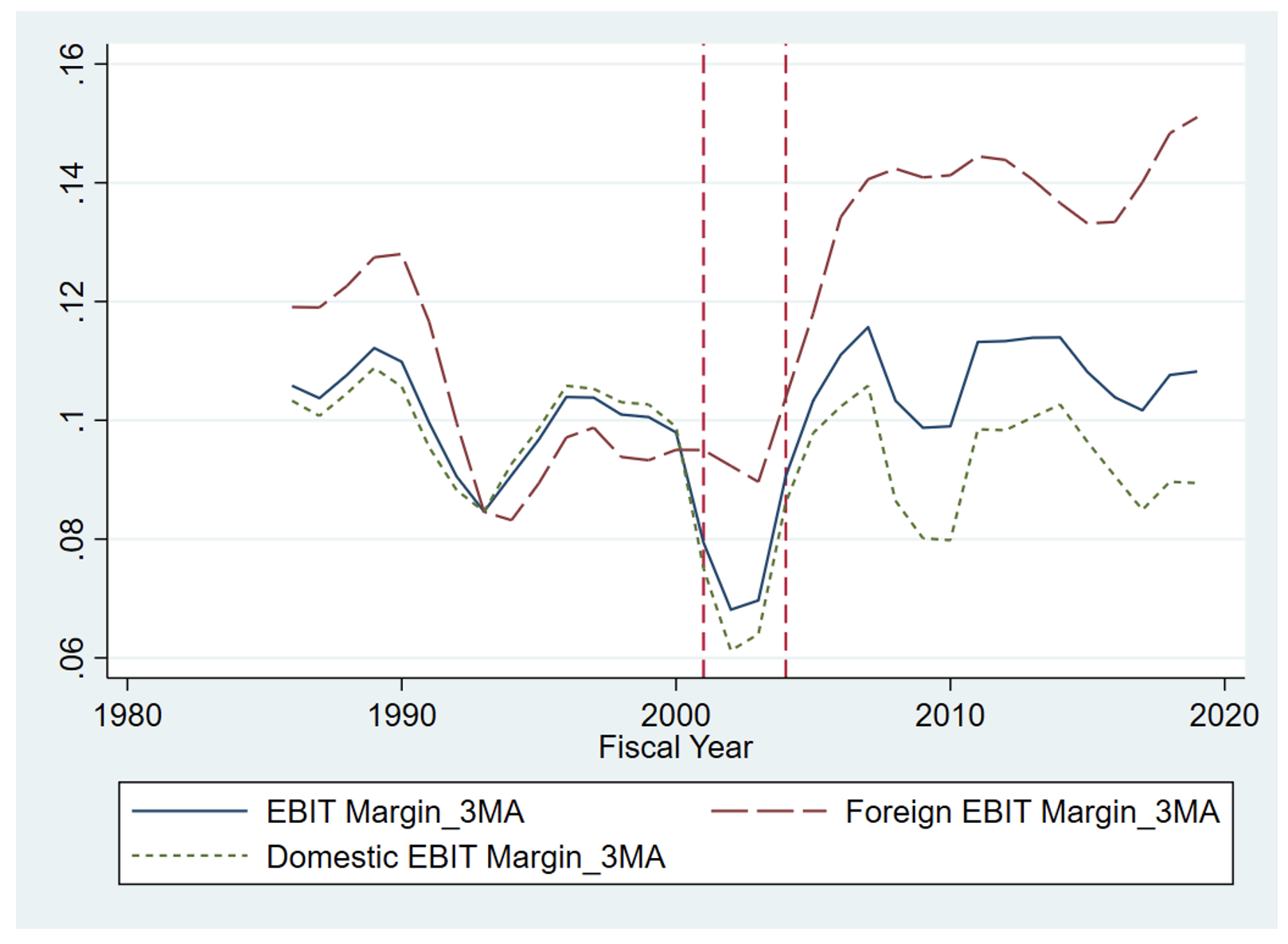

Figure 1 below (reproduced from our paper) plots the three-year-moving average of US publicly traded firms' aggregate EBIT margin, domestic EBIT margin, and foreign EBIT margin.

Figure 1 Trends in aggregate, domestic, and foreign profitability of US firms

Note: EBIT Margin denotes the aggregate EBIT ratio of US publicly traded non-financial firms to their corresponding aggregate Sales. 3MA denotes a three-year moving average. The vertical-dotted lines in red correspond to the years 2001 and 2004.

The overall profitability of US firms increased significantly during the post-globalisation period, consistent with the findings in De Loecker et al. (2020). In particular, the average aggregate EBIT margin rose from 9.6% during the pre-globalisation period to 10.7% during the post-globalisation period. Our first major insight is that this increase is driven by increased foreign profitability. The aggregate foreign EBIT margin of US firms rose significantly from an average of 10.3% pre-globalisation to 13.8% post-globalisation. Domestic profitability remained about the same during the entire sample period.

Large firms with sizeable intangible assets

A reading of the existing literature on international trade suggests large firms with significant research and development (R&D), superior technologies, brand recognition, and economies of scale are more likely to benefit more from the opportunities presented by globalisation of trade (Bernard et al. 2003, Bernard et al. 2007, Melitz and Ottaviano 2008). We use membership in the Standard and Poor 500 (S&P 500) index as a proxy for large firms.

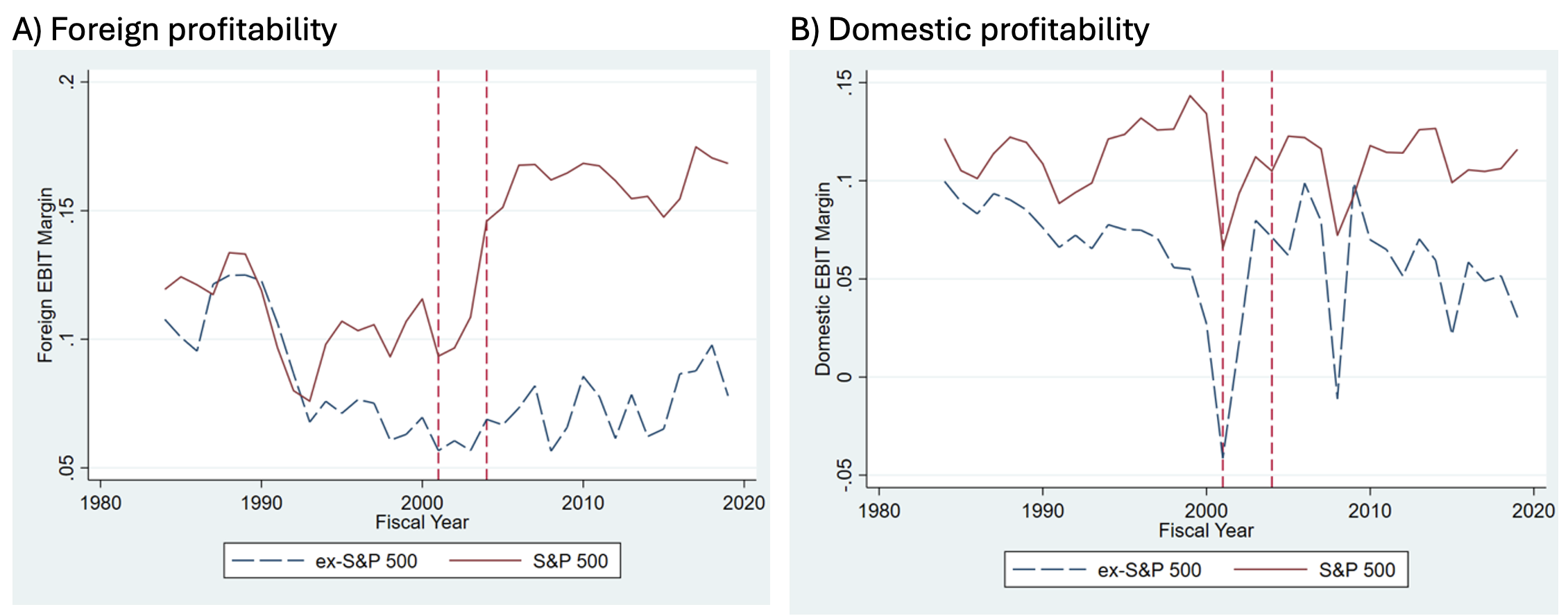

As can be seen from Figure 2 (reproduced from our paper), the average aggregate foreign EBIT margin of S&P 500 firms increased by 48% from 10.7% during the pre-globalisation period to 15.8% during the post-globalisation period. In contrast, the mean foreign EBIT margin of ex-S&P 500 firms declined from 8.8% during the pre-globalisation period to 7.4% during the post-globalisation period. Further, the domestic EBIT margins did not increase in a statistically significant manner for either group of firms.

Figure 2 Trends in domestic and foreign profitability by S&P 500 status

Note: Foreign (domestic) EBIT Margin denotes the ratio of aggregate foreign (domestic) EBIT for non-financial S&P 500 and ex-S&P 500 firms in our sample to their corresponding aggregate Sales. The vertical dotted lines in red correspond to the years 2001 and 2004.

Even among S&P 500 firms, those with higher R&D intensity (measured by the ratio of R&D expenditures to sales) experienced the most significant increases in foreign profitability following globalisation. The average foreign EBIT margin of firms in the highest R&D intensity group increased by 72% from 12.8% during the pre-globalisation period to 22.0% over the post-globalisation period. In contrast, the average foreign EBIT margin of firms in the lowest R&D intensity group increased by 21% from 10.9% to 13.2%.

Our analysis of profit margins relies on pre-tax income data from foreign and domestic operations as reported by US firms, following guidelines set by the Securities & Exchanges Commission. We recognise that several factors, including transfer pricing and outsourcing decisions by multinational firms, could have potentially contributed to greater foreign profitability reported by firms following globalisation (Guvenen et al. 2022). While the Internal Revenue Service rules require firms to use ‘arm's length’ transfer pricing, it is also well known that firms have used different tax-efficient structures to minimise their overall tax costs. However, our tests on effective tax rates (ETR) lead us to believe there is no significant difference in ETRs between firms which benefited from globalisation in terms of increased foreign profit margins and those which didn’t (between S&P 500 and ex-S&P 500 firms). Future research that incorporates data on transfer pricing and the location of production activities could provide us with a better understanding of the drivers of increased foreign profitability and foreign sales following globalisation.

Policy implications of the rise in aggregate profitability

There is some agreement in the literature that the profitability (markup) of US firms has risen over time (De Loecker et al. 2020). Policymakers would naturally be interested in understanding the underlying forces behind the increased profitability of US firms in recent years (Di Mauro et al. 2023). We provide one possible explanation for this documented increase in overall profitability. While the overall profitability and markups of US firms have risen over time, it is primarily due to increased foreign profitability, presumably made possible by the new opportunities abroad that have opened due to increased globalisation and reduced trade barriers. While greater import competition may have exerted downward pressure on domestic profitability, as evidenced by our finding of stagnating domestic profitability even for large firms, the ability of large, intangible-intensive firms to benefit from new foreign opportunities more than offset this increased domestic competition effect, resulting in increased overall aggregate profitability for the set of all publicly listed US firms.

While our analysis does not address the social welfare implications of freer global trade, it must be pointed out that increased foreign profitability does not necessarily mean that foreign consumers paid a higher price. Knowledge and know-how once created for US consumers (e.g. in creating a smartphone) can be offered to benefit those in foreign lands without the need to incur huge costs in replicating such creative efforts again. Such economies of scale rendered possible by intangibles could result in higher foreign profitability, and it is likely that those consumers also benefited from gaining access to such innovative products. In other words, it is possible that freer global trade may be beneficial to all parties involved.

References

Amiti, M, M Dai, R C Feenstra and J Romalis (2020), “How did China's WTO entry affect US prices?”, Journal of International Economics 126, 103339.

Baldwin, R (2016), “The World Trade Organization and the future of multilateralism”, Journal of Economic Perspectives 30(1): 95-116.

Bernard, A B, J Eaton, J B Jensen and S Kortum (2003), “Plants and productivity in international trade”, American Economic Review 93(4): 1268-1290.

Bernard, A B, J B Jensen, S J Redding and P K Schott (2007), “Firms in international trade”, Journal of Economic Perspectives 21(3): 105-130.

Chintha, B R, R Jagannathan and S S Sridhar (2024), “Globalization and Profitability of US Firms: The Role of Intangibles”, NBER Working Paper 32202.

De Loecker, J, J Eeckhout and G Unger (2020), “The rise of market power and the macroeconomic implications”, The Quarterly Journal of Economics 135(2): 561-644.

Di Mauro, F, M Mertens and B Mottironi (2023), “Sources of large firms’ market power and why it matters”, VoxEU.org, 17 January.

Guvenen, F, R J Mataloni Jr, D G Rassier and K J Ruhl (2022), “Offshore profit shifting and aggregate measurement: Balance of payments, foreign investment, productivity, and the labor share”, American Economic Review 112(6): 1848-1884.

Melitz, M J and G I Ottaviano (2008), “Market size, trade, and productivity”, The Review of Economic Studies 75(1): 295-316.