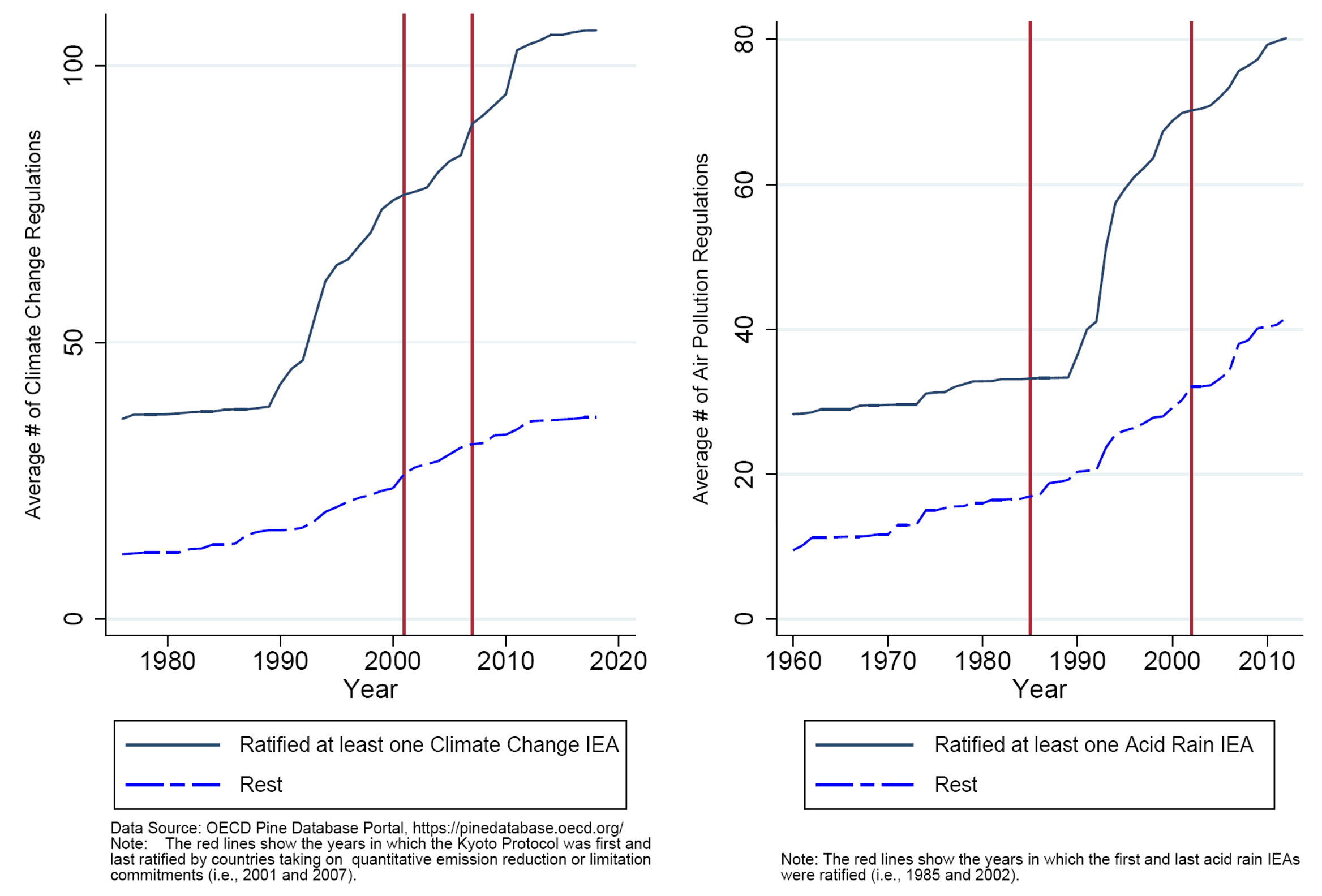

Between 1976 and 2018, manufacturing employment as a share in total employment declined from 23% to just 10% in the US and from 28% to 13% across Western Europe, with manufacturing output experiencing similar declines. Several studies (e.g. Acemoglu et al. 2016, Pierce and Schott 2016) have pointed to globalisation as a significant cause of the decline in the manufacturing sector of high-income countries. These analyses have recently received a great deal of attention as the decline in manufacturing employment has become associated with increased income inequality, significant social change, and political pressures (e.g. Autor et al. 2016, Gould 2018). It is noteworthy that many people also tie the decline in the relevance of the manufacturing sector and employment to increased environmental standards in high-income countries. For example, survey evidence suggests that a sizable majority of the American public believes that the strong environmental standards of the US place it at a competitive disadvantage in global markets. Therefore, it is perhaps not surprising that the decision to join international environmental agreements (IEAs) is often controversial with much of the discussion centring around its effects on global ‘competitiveness’ (e.g. the debate regarding whether the US should have ratified the Kyoto Protocol). Indeed, it is the case that ratification of IEAs is often accompanied by increased environmental regulation (see Figure 1 and Di Ubaldo et al. 2021). Such increased regulation could lead to increased production costs among member countries and thus to displacement of manufacturing to non-member countries that do not have similar regulatory requirements.

Figure 1 Average number of air pollution regulations

Do international environmental agreements shift aggregate manufacturing activity to non-member countries?

In Ederington et al. (2022), we employ a new dataset covering 205 countries and the 13 major air-pollution IEAs (targeting acid rain, climate change, and ozone depletion) over the period 1976-2018 to study the impact of IEA membership on a country’s trade in manufacturing. The long time span of the analysis (covering the last 40 years) also allows us to distinguish between the short-run and long-run effects of IEA ratification given possibly delayed adjustment arising from large, fixed costs and uncertain emission-abatement innovations in manufacturing industries.

Imposing some restrictions on our econometric strategy to account for endogenous treaty participation, we utilise industry-level bilateral variation in trade flows over time to identify the effect of IEA ratification on the exports of a typical manufacturing industry (i.e. an industry located at the median of the emission intensity distribution). We find statistically or quantitatively insignificant effects of IEA ratification on the exports for the typical industry in both the short and long run. Thus, there is little, if any, evidence that the proliferation of IEAs over the past five decades has been a major contributor to the general trend of manufacturing decline in high-income countries. Aggregating over all manufacturing industries and translating the results in terms of employment, there is, at most, evidence of only small job losses in the short run from IEA ratification. Indeed, there is some evidence that IEA ratification actually leads to small increases in manufacturing employment in the long run.

This result might be somewhat surprising as a previous study by Aichele and Felbermayr (2015) found that ratification of the Kyoto agreement led to a 5% decline in aggregate exports among member countries. However, this discrepancy is due to the lagged impacts of ratification. Specifically, we find that Kyoto ratification leads to a similar decline in exports of the median manufacturing industry (around 3.8%) if we restrict ourselves to their sample of countries and years (1995-2007). However, just extending the years of the sample to 2018 flips the sign of this estimate so that now Kyoto ratification leads, in this longer time span, to an increase in median industry exports by 3.4%.

Thus, the ratification of IEAs does not appear to have had much impact on aggregate manufacturing exports (or employment). Specifically, even when we find moderate negative effects of IEAs ratification on the exports of the median-polluting manufacturing industry in the short run, this negative competitive impact disappears in the long run. This is good news, since reluctance to join an IEA often revolves around concerns about the effect of IEA ratification on a country’s competitiveness (i.e. the concern that commitments required by such agreements would lead to an increase in manufacturing costs, which places that country's manufacturing base at a competitive disadvantage on world markets). Our results suggest that such competitiveness concerns are potentially overblown.

Do international environmental agreements shift emissions towards non-member countries?

A second concern with IEAs is ‘pollution leakage’: that while the stricter regulations associated with IEA ratification decrease emissions among member countries, they may also increase emissions in other countries, potentially even increasing global emissions. Although our results suggest no widespread shift in manufacturing activity towards non-member countries, pollution leakage may still occur if IEAs affect the composition of manufacturing trade and production. Specifically, if IEA ratification leads to a shift towards cleaner (less emission-intensive) production in member countries and a shift towards dirtier (more emission-intensive) production in non-member countries, then the adoption of an IEA may not even result in a reduction in global emissions. While previous studies have suggested that high-income countries off-shoring pollution is not of substantial concern (see Ederington et al. 2004, Levinson 2014) some recent studies have found evidence of pollution leakage with respect to the Kyoto protocol (e.g. Aichele and Felbermayr 2010).

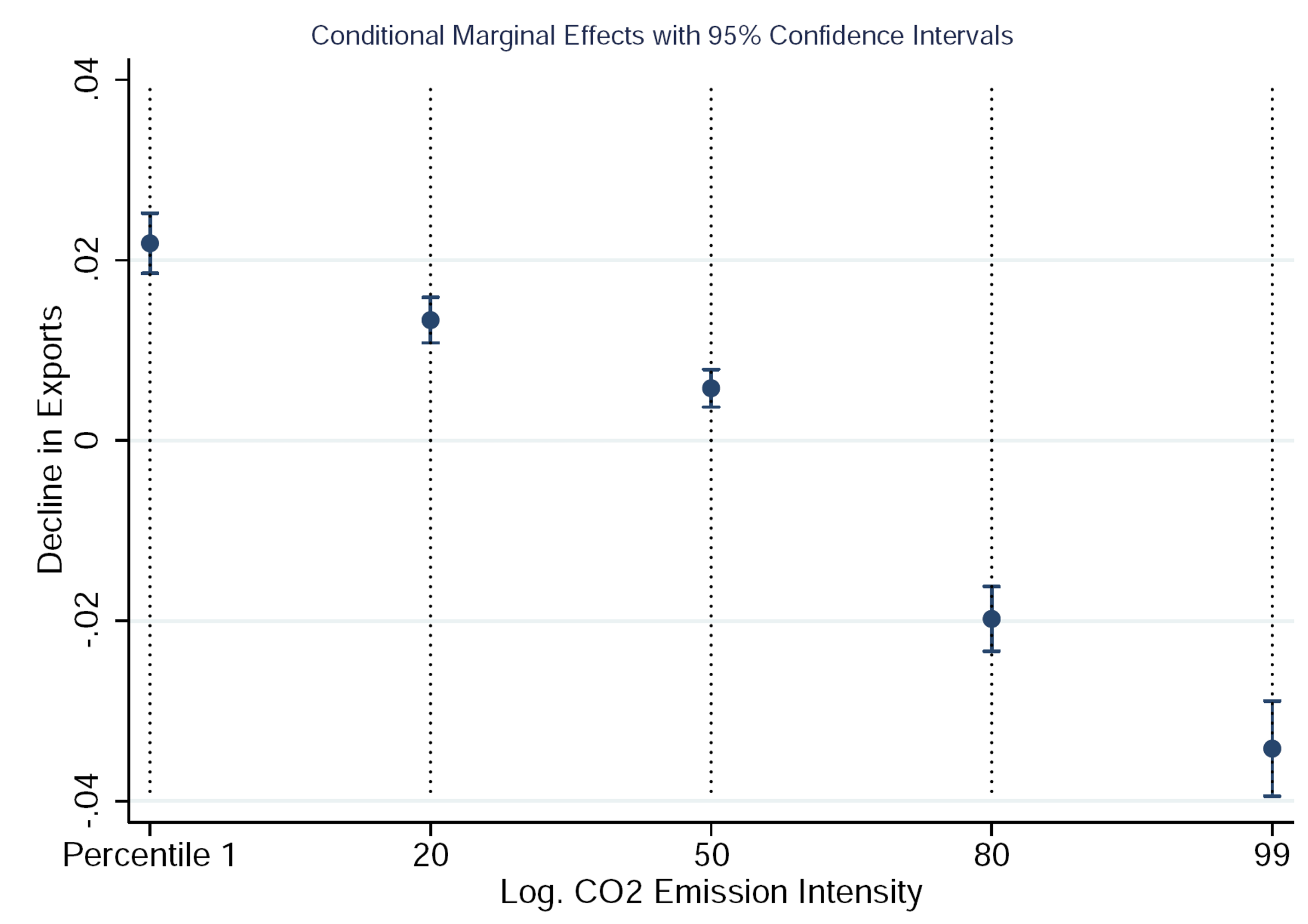

Fortunately, our empirical strategy allows us to calculate not only the impact of IEA ratification on exports and imports of the ‘typical’ manufacturing industry, but also its impact on industries at different points in the distribution (e.g. clean versus dirty industries). In our study, we uncover a significant (both quantitatively and statistically) compositional shift in exports away from dirty and towards clean industries the more IEAs an exporting country ratifies (compared to its trade partners). Figure 2 demonstrates this compositional shift as it shows the percentage change in exports from IEA ratification for industries at different levels of CO2 emission intensity. For an industry at the median level of emission intensity (i.e. pulp and paper), the ratification of an additional IEA increases exports by a relatively small 0.6%. However, for a cleaner manufacturing industry at the 20th percentile of emission-intensity (i.e. textiles), the ratification of an IEA results in more significant increase in exports of 1.3%. In contrast, ratifying an IEA results in substantial decrease in exports of 2.0% among dirtier manufacturing industries at the 80th percentile of emissions intensity (i.e. base and fabricated metals).

Figure 2 Marginal effects of international environmental agreements ratification

Thus, joining an IEA does have substantial impact on the composition of a country's manufacturing exports (i.e. a shift in net exports away from dirty and towards clean industries within countries that ratify IEAs). While this compositional shift is mostly seen as a decline in exports from dirty manufacturing industries (and a simultaneous increase in exports of clean manufacturing industries), we also see some evidence of ratifying countries increasing their imports of dirty goods from non-ratifying countries (i.e. pollution leakage). Finally, we find that this compositional shift towards exporting cleaner manufacturing industries and importing dirtier manufacturing industries are even stronger in the long run.

This is potentially bad news as it suggests that one of the mechanisms by which IEAs reduce emissions among member countries is potentially through the off-shoring of dirtier manufacturing production towards non-ratifying countries. If this is the case, that would imply that such IEAs are, perhaps, less effective in reducing global pollution than has been previously thought. It would also suggest that future IEAs should consider border tax adjustments (see Cheng and Ishikawa 2021) or other policy mechanisms aimed at reducing the potential for such pollution leakage.

References

Acemoglu, D, D Autor, D Dorn, G H Hanson and B Price (2016), “Import Competition and the Great US Employment Sag of the 2000s”, Journal of Labor Economics 34(S1): S141–S198.

Aichele, R and G J Felbermayr (2010), “Kyoto and the Carbon Content of Trade”, VoxEU.org, 4 February.

Aichele, R and G J Felbermayr (2015), “Kyoto and Carbon Leakage: An Empirical Analysis of the Carbon Content of Bilateral Trade”, Review of Economics and Statistics 97(1): 104–115.

Autor, D H, D Dorn and G H Hanson (2016), “The China Shock: Learning from Labor-Market Adjustment to Large Changes in Trade”, Annual Review of Economics 8: 205–240.

Cheng, H and J Ishikawa (2021), “Carbon Tax, Cross-Border Carbon Leakage, and Border Tax Adjustments”, VoxEU.org, 16 September.

Di Ubaldo, M, S McGuire and V Shirodkar (2021), “The Joint Effect of Private and Public Environmental Regulations on Emissions”, VoxEU.org, 3 January.

Ederington, J, A Levinson and J Minier (2004), “Trade Liberalization and Pollution Havens”, The B.E. Journal of Economic Analysis and Policy 3(2): 1–25.

Ederington, J, M Paraschiv and M Zanardi (2022), “The Short and Long-Run Effects of International Environmental Agreements on Trade”, Journal of International Economics, forthcoming.

Gould, E D (2018), “The Impact of Manufacturing Employment Decline on Black and White Americans”, VoxEU.org, 19 December.

Levinson, A (2014), “More Evidence for Technology’s Role in the Clean-Up of Manufacturing”, VoxEU.org, 14 September.

Pierce, J R and P K Schott (2016), “The Surprisingly Swift Decline of US Manufacturing Employment”, American Economic Review 106(7): 1632–1662.