The sharp spike in global inflation in 2021/22 has ignited academic and policy interest in measures of inflation expectations, because they likely play a key role in driving inflation dynamics. However, in the full information rational expectations (FIRE) models dominating in the profession until recently, there are no differences in expectations across agents since everyone is supposed to know the ‘true’ model of the economy. The academic literature has increasingly recognised the implications of the fact that this assumption does not hold up in the real world (e.g. D’Acunto et al. 2022). A better understanding of the drivers and significance of inflation expectations of different groups is therefore high on the academic agenda. The closer monitoring of the expectations of different economic actors may also be important for forecasting purposes.

Household expectations have not been studied widely but are interesting, not only because they directly matter for consumer spending (Gautier et al. 2020) but also since they often differ significantly from the expectations of professional forecasters and financial markets. In addition, they tend to be characterised by a relatively wide dispersion of expectations among households themselves (de Fiore et al. 2022). While median household expectations have been often been found to have somewhat less predictive power than inflation expectations of other actors (e.g. Verbrugge and Zaman 2021), recent research suggests that changes in the distribution of household expectations are informative. Distributional changes are not only important drivers of current inflation (Meeks and Monti 2023), but there is also reason to believe that they provide important signals about future inflation. For instance, Tsiaplias (2020), based on an Australian survey, finds evidence of predictive power of higher moments household inflation expectations’ distribution for inflation. When discussing inflationary periods in different countries, Reis (2021) points out that changes in the variance and skewness of household inflation expectations have often been leading changes in inflation. In our recent paper (Brandao-Marques et al. 2023), we systematically examine whether changes in the distribution of US household inflation expectations contain information about future inflation.

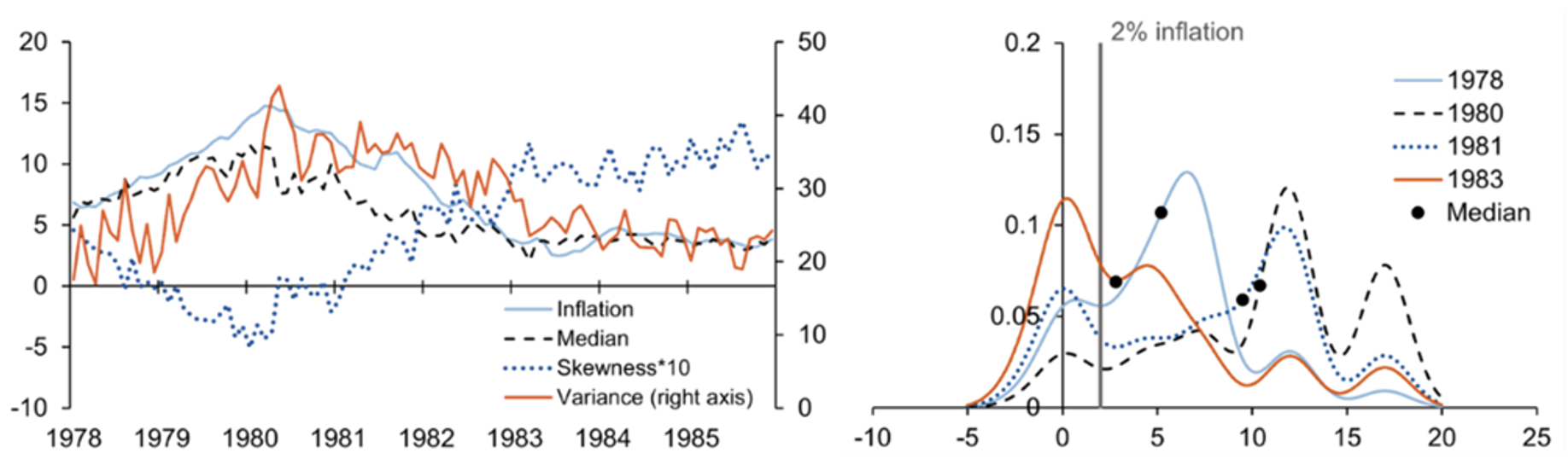

Our analysis focuses on US data, differentiating across subperiods. We start by looking at the inflation episode in the US in the late 1970s. Between 1978 and 1980, the median and variance of the distribution of household inflation expectations both increased as actual inflation rose, while skewness declined (Figure 1, left panel). These changes reflect the shift in the mass of the distribution to the right tail between 1978 and 1980, increasing the median and variance and reducing skewness (Figure 1, right panel). Starting in 1980, inflation came down, with median expectations peaking before actual inflation. The variance, which measures the disagreement between households on future inflation, continued to stay high as inflation started to fall, whereas skewness started to decline around the same time as the median peaked. Recently observed changes in the distribution of household expectations are reminiscent of these shifts four decades ago.

Figure 1 US one-year-ahead inflation expectations, 1978–1983

Sources: US Bureau of Labor Statistics, the University of Michigan’s Survey of Consumers and authors’ calculations.

Note: The LHS plot depicts inflation in month t and the moments in month t-12 to reflect the relationship analysed in the regressions.

Such patterns are consistent with a theory of staggered adjustment of expectations, as explored for example in Reis (2021). When there are reasons to expect inflation to rise, better informed households tend to move first to the right, increasing median and variance, while reducing the skewness of the distribution. On the other hand, better informed households are also the first ones to expect lower inflation as inflation is nearing its peak, lowering the median and increasing the skewness, thus reversing the pattern observed during the rise of inflation. At the same time, during that adjustment, variance can be expected to keep rising or stay elevated for longer, with informed households moving to the middle ranges of inflation, and only coming down when the mass of households begins to expect lower inflation. Therefore, whether a higher variance indicates higher or lower inflation one year ahead likely depends on the inflationary regime. On the other hand, we would expect that a lower skewness would always be indicative of higher inflation one year out.

We construct distributions based on monthly survey data from the University of Michigan’s Survey of Consumers, available since January 1978. We ascertain the informational content of household expectations, and use a simple inflation forecasting model, regressing one-year-ahead inflation on current inflation and the first three moments of the distribution of household inflation expectations.

Inflation shows substantial variability over the sample, with high-inflation periods at the beginning and the end, interspersed by the period of the ‘Great Moderation’. We therefore apply a breakpoint test to partition the sample into three different regimes, with two higher-inflation regimes in 1978M1-1990M7 and 2015M11-2022M6. As shown in the paper, the model performs best in these periods of higher inflation.

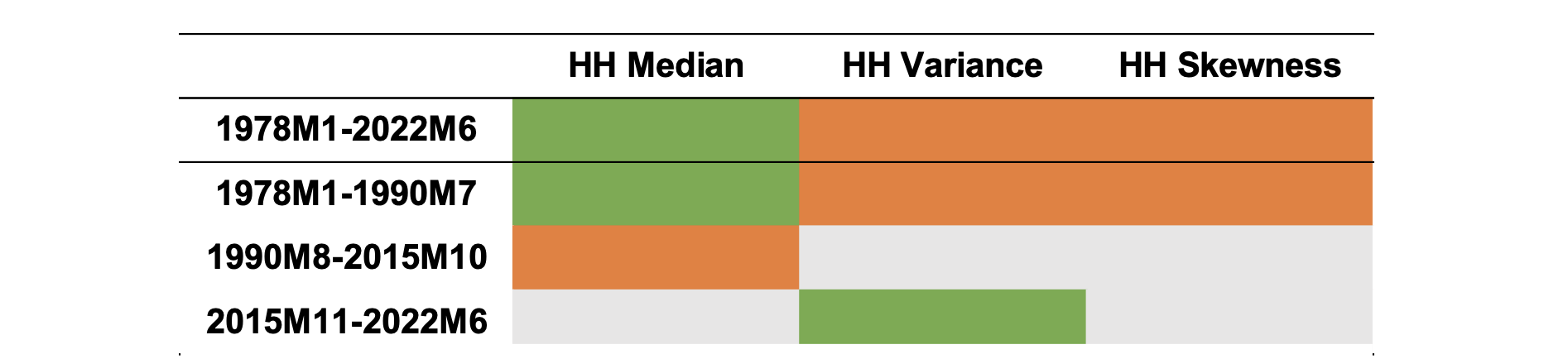

Table 1 shows whether a change in a given moment of the distribution of household expectations has a significant positive or a significant negative effect on inflation one year out. The signs of the coefficients are as expected in the two inflationary periods, where the model can explain a large share of the variation. The sign of the median coefficient is positive, while the sign of the skewness coefficient is consistently negative when significant. Interestingly, the sign of the variance coefficient is negative in the first subsample and positive in the most recent subsample. This is in line with the notion that in periods with inflation peaks (as in the end-1970s/80s period), a larger variance is associated with decreasing inflation. On the other hand, in the most recent period, which covers the lead-up to an inflation peak, an increasing variance is associated with rising inflation. More formal tests using regime dummy regressions confirm that the notion that the sign of the variance coefficient depends on the inflation regime holds in a regime-dummy regression. We also show that including higher moments improves forecasting power out-of-sample, when differentiating across low- versus high-inflation regimes.

Table 1 Predictive content of changes in moments in household expectations for 12-month-ahead CPI inflation

Source: Based on Brandao-Marques et al. (2023).

Note: A green cell indicates a positive effect that is significant on a 0.1 level. An orange cell indicates a negative effect that is significant on a 0.1 level. A grey cell indicates an effect that is not significant on a 0.1 level. Subsamples are based on the Bai-Perron (2003) global breakpoint test based on the median model, with a significance level of 5 percent and a maximum number of breakpoints of 2. Errors are Newey-West.

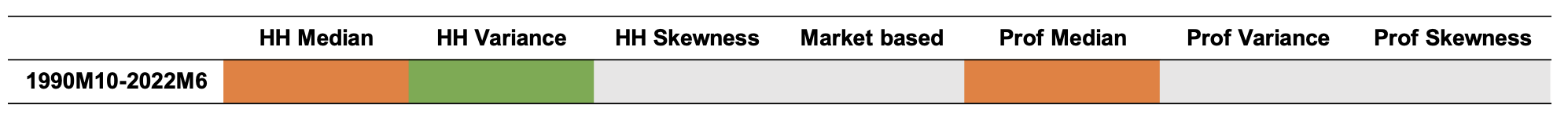

We then examine whether changes in the distribution of household inflation expectations can add information about next year’s inflation beyond that already contained in expectations by professional forecasters and financial markets. Since the survey data for professional forecasters are only available from 1989, we restrict our sample for this ‘horse race’ exercise to this shorter period. We include moments of the distribution of household expectations as well as moments of the distribution of professional forecasters’ and market-based expectations. Table 2 shows that changes in household expectation distribution do indeed add value beyond information contained in market-based and professional forecasts.

Table 2 Horse race with professional forecasters and market expectations

Source: Based on Brandao-Marques et al. (2023).

Note: A green cell indicates a positive effect that is significant on a 0.1 level. An orange cell indicates a negative effect that is significant on a 0.1 level. A grey cell indicates an effect that is not significant on a 0.1 level. Subsamples are based on the Bai-Perron (2003) global breakpoint test based on the median model, with a significance level of 5 percent and a maximum number of breakpoints of 2. Errors are Newey-West.

Our findings have important implications for the value ascribed to household inflation expectations in inflation monitoring and forecasting, and consequently, for forward-looking monetary policymaking.

However, our analysis is only a first step toward a deeper exploration of this issue. For example, while we focused in our quantitative examination on the US, similar investigations could usefully be carried out for other countries where long time series of the micro data are available. Moreover, the role of household expectations around turning points (e.g. around changes from a low- to a high inflation regime) deserves further investigation, given the results in our paper and the existing literature on attention/inattention by households.

Authors’ note: The views expressed are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect those of the Bank for International Settlements or the International Monetary Fund.

References

Brandao-Marques, L, G Gelos, D Hofman, J Otten, G K Pasricha and Z Strauss (2023), “Do Household Expectations Help Predict Inflation?”, IMF Working Paper 23/224.

D’Acunto, F, U Malmendier and M Weber (2022), “What Do the Data Tell Us About Inflation Expectations?”, NBER Working Paper No. 29825.

De Fiore, F, T Goel, D Igan and R Moessner (2022), “Rising household inflation expectations: what are the communication challenges for central banks?,” BIS Bulletin No. 55.

Gautier, E, E Mengus and P Andrade (2020), “How households’ inflation expectations matter,” VoxEU.org, 4 August.

Meeks, R and F Monti (2023), “Heterogeneous beliefs and the Phillips curve”, Journal of Monetary Economics 139: 41-54.

Reis, R (2021), “Losing the Inflation Anchor”, CEPR Discussion Paper No. 16664.

Tsiaplias, S (2020), “Time-Varying Consumer Disagreement and Future Inflation”, Journal of Economic Dynamics & Control 116, 103903.

Verbrugge, R J and S Zaman (2021), “Whose Inflation Expectations Best Predict Inflation?”, Federal Reserve Bank of Cleveland Economic Commentary 2021-19.