Ensuring equitable access to quality education is key to addressing social and economic inequalities. Governments in the 21st century face the challenge of making education systems inclusive, providing equal opportunities for success based on individual ability and effort, rather than on uncontrollable socioeconomic or cultural background (Roemer 1998). Although Western European educational systems are highly accessible, inequalities in the acquisition of educational skills are large and significantly influenced by the socioeconomic and cultural contexts of different households (Sirin 2005, Jerrim et al. 2019). Moreover, economic inequality has been associated with reduced educational intergenerational mobility (Blanden et al. 2022, 2023). It is therefore crucial that education systems provide a level playing field for all students, regardless of their personal circumstances.

Cognitive traits such as patience (understood as the ability to delay gratification) or risk-taking have already been identified as determinants of differences in educational achievement (Hanushek et al. 2020, 2022, 2023a, 2023b), as have organisational factors such as mentoring programmes for disadvantaged students (Resnjanskij et al. 2023a,b) or teachers’ use of instructional time (Burgess et al. 2023a,b).

To contribute to the understanding of how to address inequitable inequalities in achievement, in a recent study (Marrero et al. 2023) we investigate the key factors that affect not only student achievement but the part of student achievement that is contextual (family and school) and not due to talent or effort. The factors we aim to disentangle can be considered mediators of inequality of opportunities in educational achievement in Western European countries. Our results show that some factors available in the PISA 2018 dataset (reading skills, expectations and grade repetition) can account, on average, for one-fifth of the inequality of opportunities in educational achievement in the countries we studied.

The PISA 2018 database assesses the competencies of 15-year-old students in science, mathematics, and reading. We present here the results for science, due to science’s strong correlation with the other two subjects and its higher association with curricular achievement (Pulkkinen and Rautopuro 2022).

We first analyse the levels of inequality of opportunities in educational achievement in Europe and then assess the weight of each contributing circumstance. Finally, we evaluate the mediating factors that could be addressed to reduce the inequalities.

Inequality of opportunities in educational achievement in Europe

We find significant within-country differences in achievement across Western European countries. The extent to which these are due to circumstances beyond students’ control – factors unrelated to their talent or effort – is captured by our measure of inequality of opportunities in educational achievement. In our most comprehensive model, this includes family socioeconomic background and school environment.

Our method follows the parametric regression procedure of Ferreira and Gignoux (2014), using educational attainment as the dependent variable affected by the set of circumstances. The resulting inequality of opportunity (IO) ratio, expressed as a percentage, represents the variance in educational achievement explained by these circumstances.

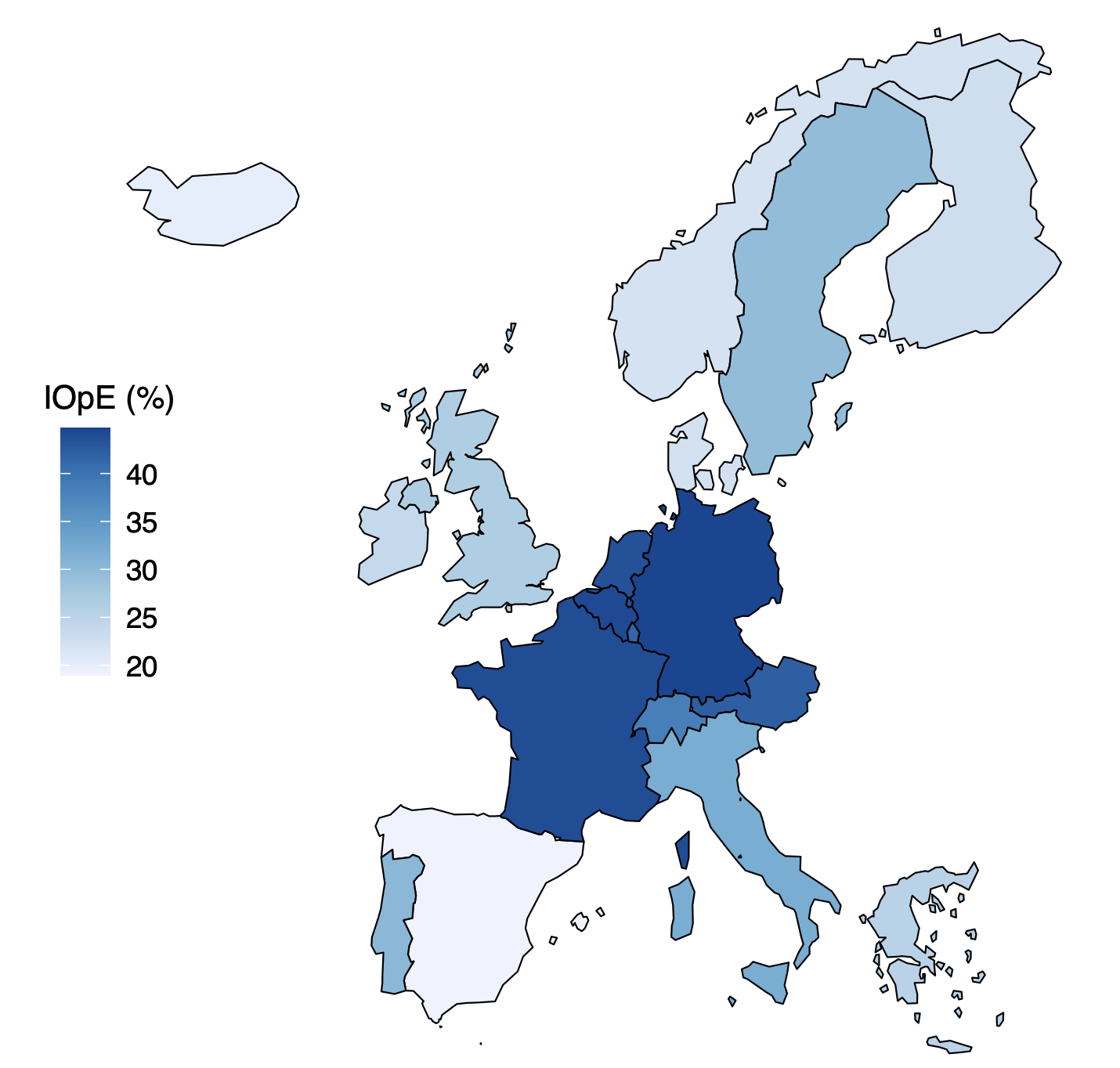

Our results show strong regional disparities. Figure 1 shows the values from the first column of Table 1. Most Nordic countries, as well as Ireland and Spain, have lower values for inequality of opportunities in educational achievement. Conversely, Central European countries, including Belgium, France, Germany, and the Netherlands, have significantly higher inequality. In the middle of the table are Italy, Portugal, Sweden, and the UK.

Figure 1 Inequality of opportunity in educational achievement in Western Europe

Notes: Inequality of opportunity (IOpE) is measured as a percentage over total inequality in educational achievement in PISA 2018 in science. Circumstances included are gender and migrant status, mother’s and father’s education, mother’s and father’s occupation, household wealth, cultural resources at home, number of books at home, and school characteristics (ownership and peer’s effect). Source: Author’s elaboration from PISA 2018 database.

Contributing circumstances

To identify the circumstances that matter the most to the inequality of opportunities in educational achievement, we used a regression-based decomposition method that decomposes the predicted portion of educational achievement into contributing circumstances. This method, which allows for an exact additive decomposition (Shorrocks 1982, Fields 2003), has been used in regression models similar to ours (Brewer 2016).

In addition to gender, we consider circumstances of family background and school context. Family background includes parental education and occupation, household wealth, migrant status, and cultural environment (quantified by the number of books at home), despite potential reporting issues (Engzell 2021). School-related factors, often neglected in existing research, include school ownership (private or public) and the socioeconomic status of the school’s students.

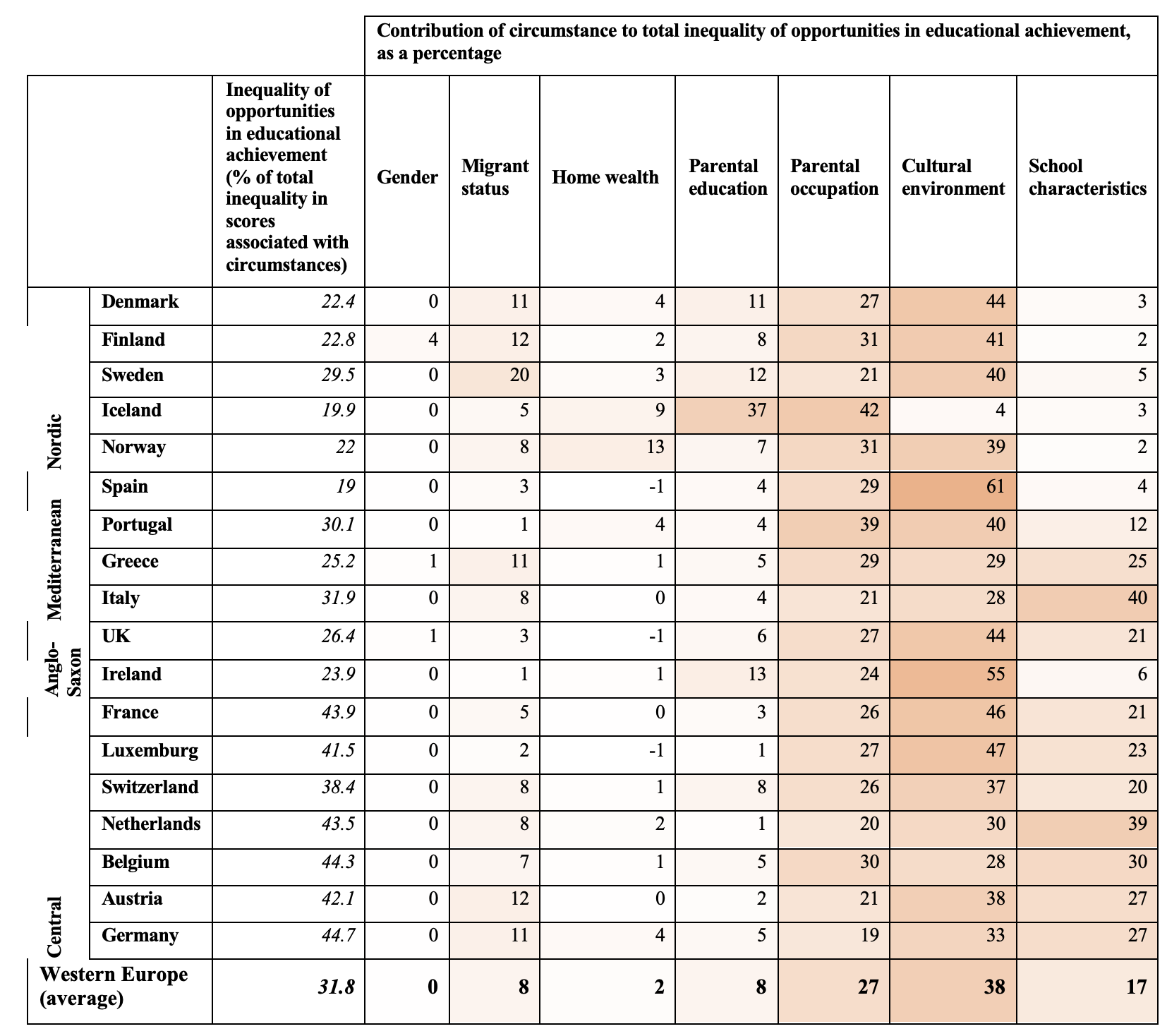

Table 1 shows the relative weight of each circumstance group (columns 2–7) in the total value of the measure for inequality of opportunities in educational achievement. Our analysis highlights the household’s cultural environment, specifically the number of books, as the most important contributor to inequality of opportunities in educational achievement. This aligns with previous findings (Fuchs and Woessmann 2007, Strietholt et al. 2019) that identify books at home as a key indicator of student performance. In science, the cultural environment contributes on average 38% to the inequality of opportunities in educational achievement in the countries analysed, with a notable contribution in France, Ireland, Luxembourg, and Spain and sizeable in all countries except Iceland. Parental occupation and school characteristics follow in importance, contributing on average 27% and 17%, respectively.

Table 1 Relative contribution of selected circumstances to inequality of opportunities in educational achievement in Western Europe (in science)

Notes: Estimation of contributions using a variance decomposition method of the educational achievement conditional distribution (Fields 2003). Groups include: gender; immigrant status (1st and 2nd generation immigrants and language spoken at home); wealth (possession of household property); parental education (mother’s and father’s education); parents’ occupation (occupational status of the mother and father); cultural environment (quantity of books in the home and possession of cultural property); school characteristics (peer students’ average socioeconomic level and ownership status of the school).

While family cultural environment and parental occupation are universally significant, the impact of school characteristics varies across countries. In regions with higher inequality of opportunities in educational achievement, school characteristics tend to contribute more, suggesting a link with early student tracking and variability in school performance due to ownership type or socioeconomic status of students. Conversely, in the Nordic countries and Spain, school characteristics have a minimal impact on inequality of opportunities.

Significantly, once the main factors of cultural environment, parental occupation, and school characteristics are considered, other circumstances like parental education and household wealth have only a marginal impact on the inequality of opportunities in educational achievement. This suggests that differences in the inequality of opportunities are less about parental education or wealth per se, and more about how these factors influence the home’s cultural environment or occupational status. Gender and immigrant status have a small relative contribution except in countries like Sweden, where immigrant status has a larger impact.

Channels of inequality of opportunity in educational achievement

The impact of each circumstance on educational performance is not always direct. For instance, a wealthier household might have better access to the Internet or technology, which in turn might support learning. Similarly, households with different cultural contexts might foster reading skills or influence students’ expectations and motivation differently, which could be crucial for academic performance.

Thus, we aim to identify the extent to which these variables conditioned by circumstances affect student scores. We select potential channels from the PISA 2018 dataset primarily by the correlation of their variability with the set of circumstances. Factors like students’ expectations and academic life (educational and occupational expectations, grade repetition, ICT access), and attitudes, habits, and skills in reading are considered. Second, we investigate the extent to which these variables channel inequality of opportunities in educational achievement – that is, the extent to which their distribution explains the distribution of scores predicted by circumstances (Palomino et al. 2019).

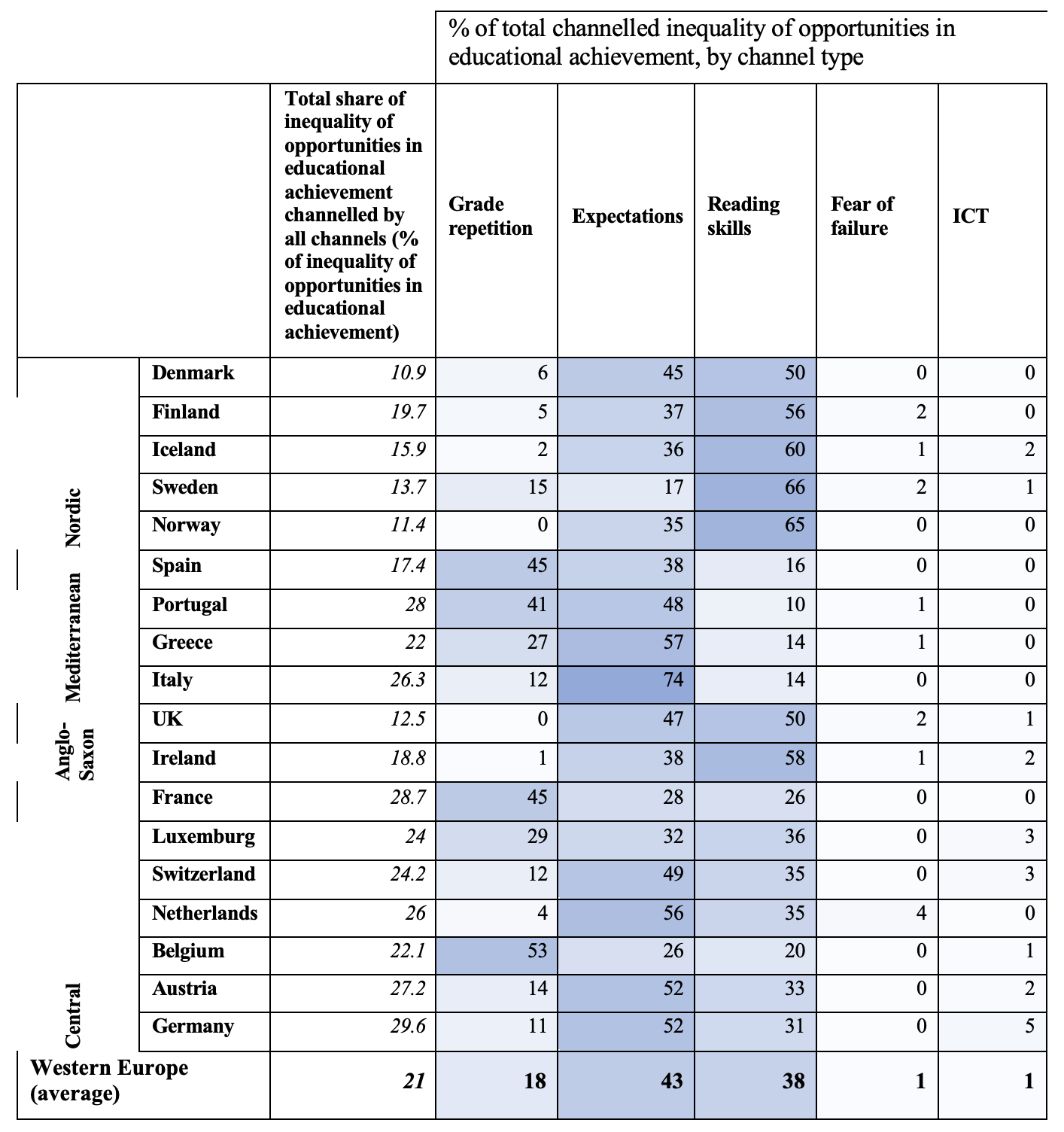

We find that, on average, more than one-fifth of the inequality of opportunities in educational achievement can be mediated by the common set of channelling factors that we considered. The first column in Table 2 shows the total contribution of the channels (grade repetition, expectations, reading skills, fear of failure, ICT) to the inequality of opportunities in educational achievement in science for each country. In Nordic and Anglo-Saxon countries and Spain, a smaller share of inequality is channelled by the set of mediators, while in Central European countries, they channel a larger share. In all cases, the remaining unchanneled share includes the direct effect of circumstances on performance or the effect of unobserved channels.

Table 2 Relative contribution of channels to inequality of opportunities in educational achievement in Western Europe (in science)

Notes: The first column indicates the percentage of the circumstance-conditioned outcome in science (inequality of opportunities in educational achievement) that is explained by the full set of potential channels included in the table. The remaining columns show the percentage of the total channelled share attributed to each channel (higher percentages in deeper colours). Expectations include occupational and educational expectations of the student. Reading skills include reading ability, reading comprehension, and reading habits.

The remaining columns in Table 2 show the relative contribution of each mediator to the total inequality of opportunities in educational achievement channelled. Grade repetition accounts for 18% of the total inequality channelled by this set of variables, but with large cross-country disparities. In some countries (notably Belgium, France, Portugal and Spain but also Greece and Luxembourg), repetition is associated with differences in achievement due to different circumstances (and not effort or talent). This means that repetition does not bring results closer together for students from different circumstances. On the contrary, it is correlated with the divergence of results between students from different backgrounds.

The share of reading skills and habits in total inequality channelled is 38% on average across countries. Reading-related channels have a higher weight in Nordic and Anglo-Saxon countries, suggesting a focus on reading promotion could mitigate educational inequalities across students from diverse backgrounds. Early intervention is recommended, as skills development is cumulative.

Student expectations stand out as a key channel, accounting on average for 43% of the total inequality of opportunities channelled. Expectations are particularly important in Central European and Mediterranean countries, as well as in the UK. Policies that enhance students’ motivation by providing clear information (to both students and parents) on potential educational pathways and employment goals could effectively improve educational opportunities in these regions. However, these interventions must reach students from all backgrounds and particularly target those from more disadvantaged backgrounds.

The policy implications are clear: while long-term changes in circumstances may be generational, interventions targeting these channels can more immediately disrupt the link between background disparities and educational performance. Addressing differences in expectations, reading habits, skills, and academic pathways offers a concrete policy avenue for reducing unfair educational inequalities that are caused by the lottery of life.

References

Blanden, J, M Doepke, and J Stuhler (2022), “Unequal education and the ‘Great Gatsby Curve’”, VoxEU.org, 20 December.

Blanden, J, M Doepke, and J Stuhler (2023), “Educational inequality”, in Handbook of the Economics of Education, Vol. 6, Elsevier.

Brewer, M, and L Wren‐Lewis (2016), “Accounting for changes in income inequality: decomposition analyses for the UK, 1978–2008”, Oxford Bulletin of Economics and Statistics 78(3): 289–322.

Burgess, S, S Rawa, and E S Taylor (2023a), “Teachers’ use of class time and student achievement”, Economics of Education Review 94: 102405.

Burgess, S, S Rawa, and E S Taylor (2023b), “Teachers’ use of class time and student achievement”, VoxEU.org, 19 February.

Engzell, P (2021), “What do books in the home proxy for? A cautionary tale”, Sociological Methods and Research 50(4): 1487–514.

Ferreira, F, and J Gignoux (2014), “The measurement of educational inequality: Achievement and opportunity”, The World Bank Economic Review 28(2): 210–46.

Fields, G (2003), “Accounting for income inequality and its changes: A new method, with application to the distribution of earnings in the US”, Research in Labour Economics 22: 1–38.

Fuchs, T, and L Woessmann (2007), “What accounts for international differences in student performance? A re-examination using PISA data”, Empirical Economics 32(2–3): 433–64.

Hanushek, E A, L Kinne, P Lergetporer, and L Woessmann (2020), “Patience, risk-taking, and international differences in student achievement”, VoxEU.org, 2 August.

Hanushek, E A, L Kinne, P Lergetporer, and L Woessmann (2022), “Patience, risk-taking, and human capital investment across countries”, Economic Journal 132(646): 2290–307.

Hanushek, E A, L Kinne, P Sancassani, and L Woessmann (2023a), “Patience and the North-South divide in student achievement in Italy and the US”, VoxEU.org, 11 October.

Hanushek, E A, L Kinne, P Sancassani, and L Woessmann (2023b), “Can patience account for subnational differences in student achievement? Regional analysis with Facebook interests”, NBER Working Paper w31690.

Jerrim, J, L Volante, D A Klinger, and S V Schnepf (2019), “Socioeconomic inequality and student outcomes across education systems”, Socioeconomic Inequality and Student Outcomes: Cross-National Trends, Policies, and Practices, Singapore: Springer.

Marrero, G A, J C Palomino, and G Sicilia (2023), “Inequality of opportunity in educational achievement in Western Europe: Contributors and channels”, Journal of Economic Inequality.

Palomino, J C, G A Marrero, and J G Rodríguez (2019), “Channels of inequality of opportunity: The role of education and occupation in Europe”, Social Indicators Research 143(3): 1045–74.

Pulkkinen, J, and J Rautopuro (2022), “The correspondence between PISA performance and school achievement in Finland”, International Journal of Educational Research 114: 102000.

Resnjanskij, S, J Ruhose, S Wiederhold, L Woessmann, and K Wedel (2023a), “Mentoring improves the school-to-work transition of disadvantaged adolescents”, VoxEU.org, 17 December.

Resnjanskij, S, J Ruhose, S Wiederhold, L Woessmann, and K Wedel (2023b), “Can mentoring alleviate family disadvantage in adolescence? A field experiment to improve labor-market prospects”, Journal of Political Economy, forthcoming.

Shorrocks, A F (1982), “Inequality decomposition by factor components”, Econometrica 50: 193–211.

Strietholt, R, and A Strello (2022), “Socioeconomic inequality in achievement: Conceptual foundations and empirical measurement”, International Handbook of Comparative Large-Scale Studies in Education: Perspectives, Methods and Findings, Springer.

Roemer, J E (1998), Equality of opportunity, Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press.

Sirin, S R (2005), “Socioeconomic status and academic achievement: A meta-analytic review of research”, Review of Educational Research 75(3): 417–53.