Despite progress towards a banking union in the EU, European banks continue to be confronted with a highly divergent application of insolvency laws. A recent survey of European banks conducted by the European Banking Authority (2020) shows that this divergence has given rise to widely varying loan resolution outcomes. To eliminate the variation in the application of insolvency laws, the European Commission (2022) has recently proposed a directive that aims to harmonise insolvency law in the EU.

Inefficient loan resolution regimes can promote the creation of zombie firms that continue to receive credit from banks despite being insolvent, since such regimes may enhance incentives for banks to evergreen loans to weak firms to prevent the realisation of loan losses.

Altman et al. (2022) and Albuquerque and Iyer (2023) find that zombie firms are more prevalent in countries with inefficient debt enforcement and less prepared corporate insolvency frameworks. A substantial literature, including Peek and Rosengren (2005), Caballero et al. (2008), and Acharya et al. (2022), has documented that zombie lending generally has negative economic repercussions, as it may keep inefficient zombie firms afloat and crowd out the activities of healthy firms.

In a new paper (Demirgüç-Kunt et al. 2023), however, we show that inefficient resolution regimes may have a silver lining, as they serve to insulate weak firms from financial shocks, measured as low bank capitalisation, and macroeconomic shocks, measured as low or negative GDP growth. Specifically, we find that firm-level financing, employment, and sales are stabilised by inefficient loan enforcement in the face of negative bank-level and overall macroeconomic shocks.

While these insulating properties of inefficient loan enforcement by themselves can be taken to be advantageous, we continue to think that reform that makes loan enforcement more efficient in Europe is desirable.

Our study examines European firms and banks during 2009-2019, making use of the European Banking Authority (EBA) data on the loan resolution experiences of European banks.

Firm-level data are from Amadeus and bank-level data from SNL.

The European Banking Authority data on loan enforcement outcomes in Europe

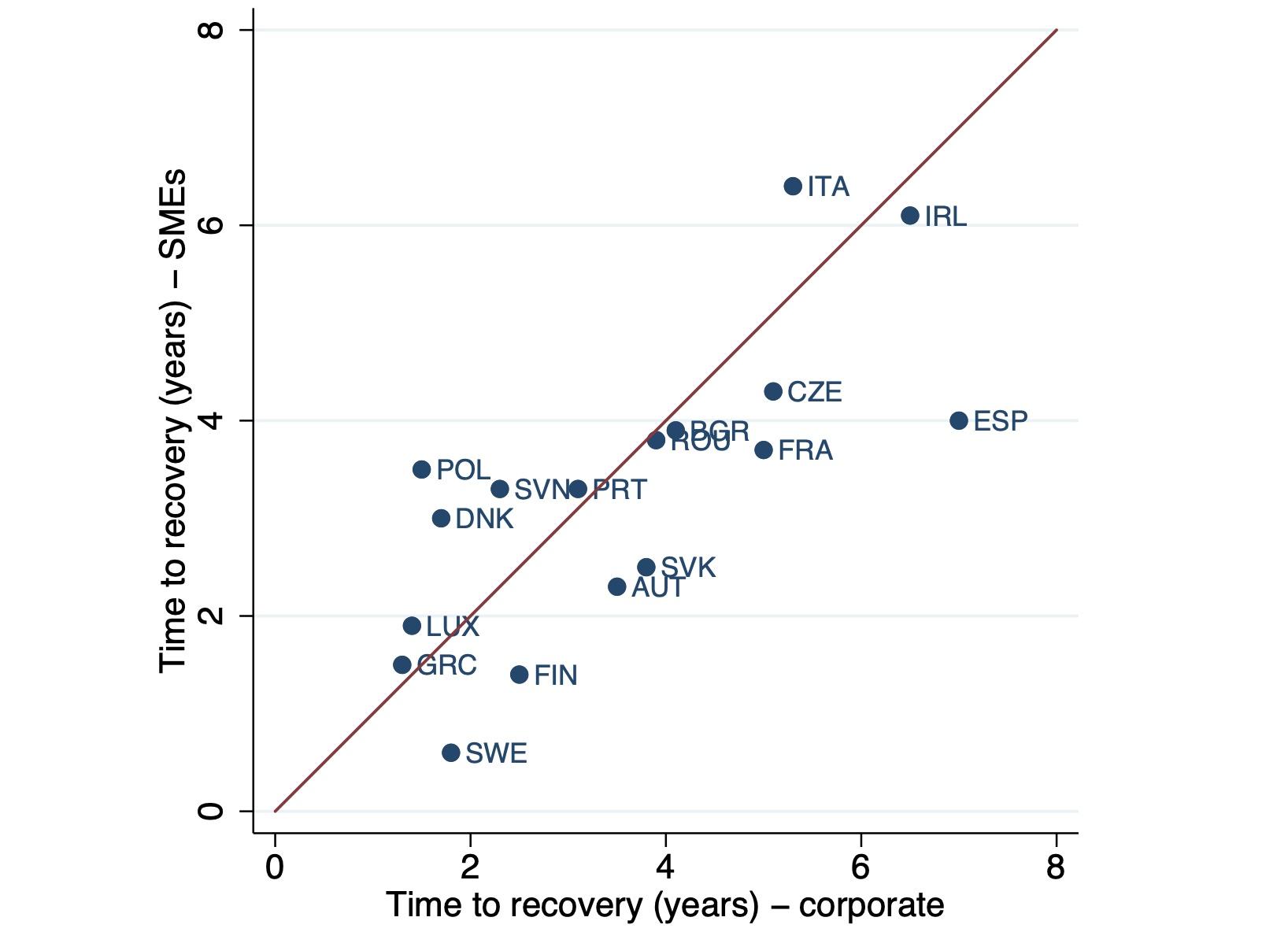

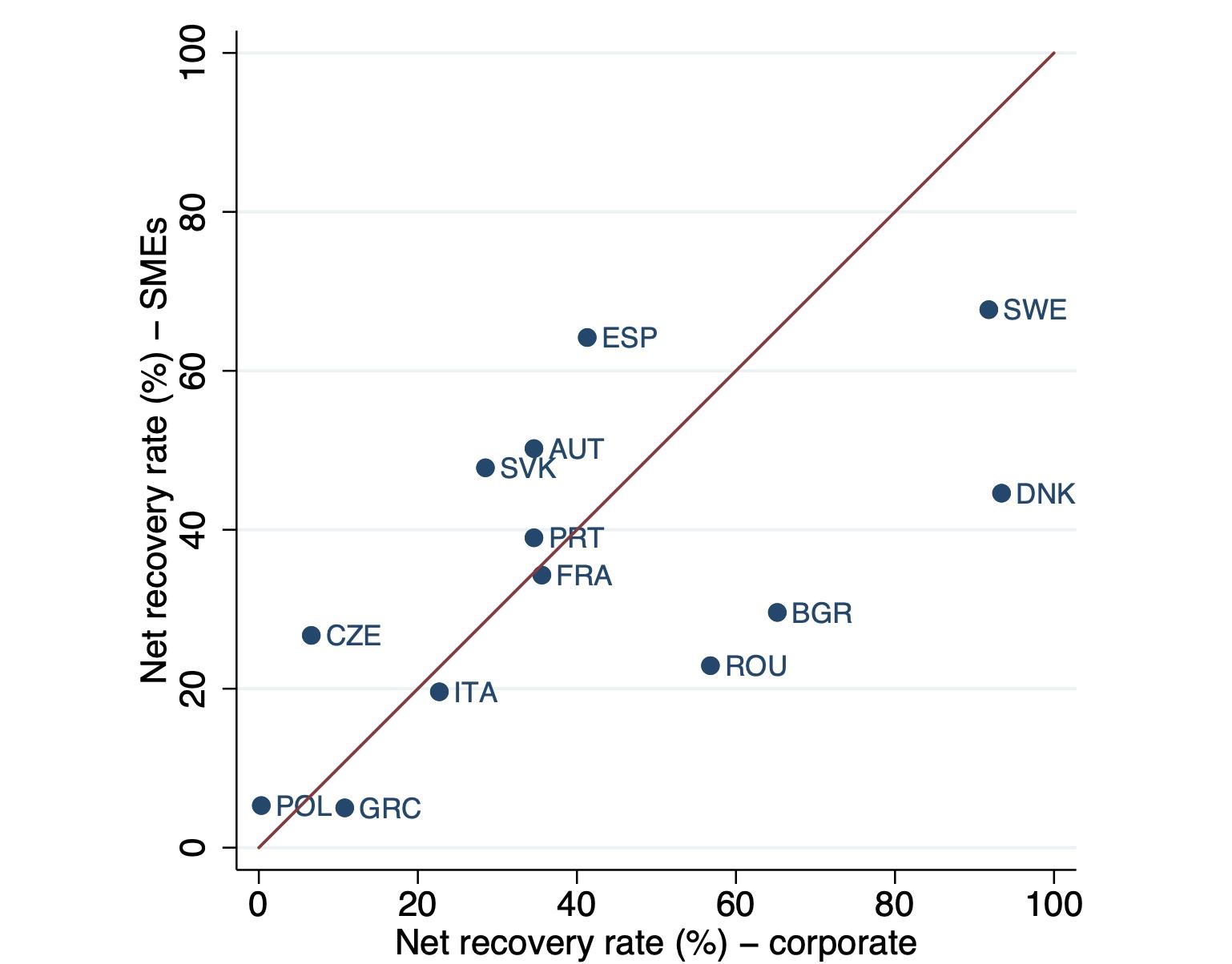

The European Banking Authority has collected data on time to recovery and on loan recovery proceeds from a set of 160 banks that were chosen to be representative with respect to their size and business models. The loan enforcement data pertain to loan enforcement episodes that were completed and/or initiated during 2015-2018. Average loan enforcement data are reported at the national level, but with separate measures for larger corporations and small and medium enterprises (SMEs). The average loan recovery period is 3.3 and 3.0 years for EU corporates and small and medium enterprises, respectively. Figure 1 shows that the average time to recovery for loans to corporates relative to loans to SMEs varies among EU member states. Average loan recovery rates (net of judicial costs) for EU corporates and SMEs are 41.6% and 39.6%, respectively. Figure 2 shows that the recovery rates for loans to corporates relative to loans to SMEs also tend to vary among European countries.

Figure 1 Time to recovery for loans to corporates and small and medium enterprises in the EU

Notes: This figure shows the average time to recovery for each EU member state separately for corporates and for small and medium enterprises (SMEs). The red line represents the 45-degree line. Data are from the European Banking Authority (2020).

Figure 2 Net recovery rates for loans to corporates and small and medium enterprises in the EU

Notes: This figure shows the average net recovery rate for each EU member state separately for small and medium enterprises (SMEs) and corporates. The red line represents the 45-degree line. Data are from the European Banking Authority (2020).

The insulating properties of inefficient loan enforcement

Generally, banks with low capitalisation rates can provide fewer new loans, and hence firms that are tied to a bank with lower capitalisation are expected to experience lower debt growth. However, we find that the tendency for a firm with ties to a bank with low capitalisation to experience lower debt growth is attenuated if the firm is located in a country with less efficient loan enforcement. Specifically, our estimation implies that a one standard deviation (0.025) reduction in the Tier 1 regulatory capital ratio of a firm’s bank reduces the firm’s debt growth by 0.34% less if the country’s time to recovery is high (at the 75th percentile) rather than low (the 25th percentile). Furthermore, an equal reduction in bank capitalisation reduces the firm’s debt growth by 0.57% less if the loan recovery rate is low rather than high. These insulating properties of inefficient loan enforcement for the firm’s debt growth are small, but they are large enough to have real implications. In particular, we find that inefficient loan enforcement also stabilises a firm’s employment and sales in the face of shocks to bank capitalisation.

During economic downturns, banks as well as their borrowers tend to be weaker. This suggests that loan enforcement inefficiency could also stabilise firms confronting macroeconomic shocks, especially in the case of zombie firms. To investigate this, we apply the definition of zombie firms of De Jonghe et al. (2021), which compares a firm’s cash flow to its interest expenses.

We find that the debt growth of a zombie firm relative to a non-zombie firm is 0.22% higher following a one standard deviation (0.9%) decline in EU GDP growth if the firm is located in a country with slow rather than fast loan recovery. Consistent with this, we find evidence that zombie firms experience relatively higher employment and sales growth rates, and lower default probabilities during economic downturns, if located in countries characterised by less efficient loan enforcement.

Conclusion

Inefficient loan enforcement can partially insulate firms from negative financial sector and macroeconomic shocks, as it reduces incentives for banks to enforce nonperforming loans to weak firms. By themselves, these insulating properties can be taken to be advantageous, but prior research has documented that zombie lending prevents the timely restructuring of inefficient firms and has negative spillovers to healthy firms, hampering long-term economic growth. Reform of insolvency law in the EU, as envisioned by the European Commission, will reduce the stabilising effects of loan enforcement inefficiency in countries that currently have inefficient insolvency laws, but overall such reform should have a long-term positive effect on the European economy.

References

Acharya, V, M Crosignani, T Eisert and S Steffen (2022), “Zombie lending: Theoretical, international and historical perspectives”, Annual Review of Financial Economics 14: 21-38.

Albuquerque, B and R Iyer (2023), “The rise of the walking debt: Zombie firms around the world”, VoxEU.org, 28 August.

Altman, E, R Dai and W Wang (2022), “Global zombies”, Working Paper, New York University.

Becker, B and V Ivashina (2022), “Weak corporate insolvency rules: The missing driver of zombie lending”, AEA Papers and Proceedings 118: 516-20.

Caballero, R, T Hoshi and A Kashyap (2008), “Zombie lending and depressed restructuring in Japan”, American Economic Review 98: 1943-1977.

De Jonghe, O, K Mulier and I Samarin (2021), “Bank specialization and zombie lending”, National Bank of Belgium Working Paper No 404.

Demirgüç-Kunt, A, B Horváth and H Huizinga (2023), “Loan recoveries and the financing of zombie firms over the business cycle”, CEPR Discussion Paper 18351.

European Banking Authority (2020), “Report on the benchmarking of national loan enforcement frameworks”.

European Commission (2022), “Proposal for a directive of harmonizing certain aspects of insolvency law”.

Mora-Sanguinetti, J, M Martinez-Matute and M Garcia-Posada (2017), “Credit, crisis and contract enforcement: evidence from the Spanish loan market”, European Journal of Law and Economics 44: 361-383.

Peek, J and E Rosengren (2005), “Unnatural selection: Perverse incentives and the misallocation of credit in Japan”, American Economic Review 95: 1144-1166.

Petroulakis, F and D Andrews (2019), “Zombie firms, weak banks, and depressed restructuring in Europe”, VoxEU.org, 4 April.