How do policy and other barriers to flows of goods and capital shape cross-country patterns of economic growth and income convergence? The textbook neoclassical growth model remains a key benchmark for thinking about cross-country income dynamics (Solow 1956, Swan 1956). In the closed-economy version of this model, each country converges along a transition path to its own steady-state level of income per capita, as determined by its production technology and preference parameters. In open economy versions of this model, strong assumptions are typically made about substitutability in goods and capital markets. Often goods are assumed to be homogeneous across countries, or trade between countries is assumed to be costless, whereas conventional quantitative trade models feature both imperfect substitutability across countries and trade frictions. Similarly, capital is often assumed to be homogeneous, which, with competitive markets, implies perfectly elastic flows of capital between countries to arbitrage away differences in rates of return.

Our model

We generalise the closed-economy neoclassical growth model (CNGM) to allow for costly international trade and capital holdings with imperfect substitutability to shed new light on the determinants of cross-country economic growth and income convergence (Kleinman et al. 2024). We develop a tractable, multi-country model that is amenable to quantitative analysis, which simultaneously incorporates international goods trade and capital allocations across countries, as well as intertemporal savings decisions over time. We consider an Armington specification, in which goods are differentiated by country of origin. Goods can be traded between countries subject to iceberg trade costs. The representative agent in each country chooses how much of the final consumption index to consume and save (as for example in Angeletos 2007 and Moll 2014). In contrast to conventional frameworks, wealth in each country can be invested in any country around the world, subject to capital market frictions and idiosyncratic heterogeneity in investment returns. The model thus determines both the allocation of wealth at a point in time and the accumulation of wealth over time. As in the CNGM, each country converges to its own steady-state, but this steady-state now depends not only on domestic productivity, but also on foreign productivity and goods and capital market frictions.

With open goods markets, domestic capital accumulation that increases output of a country's good leads to a deterioration in its terms of trade, at a rate that depends on the degree of substitutability in goods markets. With open capital markets, domestic capital accumulation can be achieved through both domestic saving and inflows of foreign capital, where each country faces an upward-sloping supply function for foreign capital, whose slope depends on the degree of substitutability in capital markets. In general, the stock of wealth in each country differs from its stock of capital. Therefore, some countries can specialise as exporters of capital services and importers of goods, while others specialise as exporters of goods and importers of capital services, even in the absence of current account imbalances. With an intertemporal savings decision, some countries can spend more than their income and incur current account deficits, while others spend less their than their income and enjoy current account surpluses.

Our specification rationalises a number of the observed features of international capital holdings that are discussed in Obstfeld and Rogoff (2000). First, it is consistent with empirical findings that international capital holdings are well approximated by a gravity equation (e.g. Portes and Rey 2005), if bilateral capital frictions are increasing in the bilateral distance between countries. Second, it is in line with empirical findings of home bias in international capital allocations (e.g. French and Poterba 1991), because managing capital is more costly abroad than at home. Third, it accounts for a strong positive correlation between domestic saving and investment rates (e.g. Feldstein and Horioka 1980), because foreign capital is an imperfect substitute for domestic capital, and is subject to greater capital market frictions than domestic capital. Fourth, it generates larger gross capital flows than net capital flows, because each investor country holds a positive amount of capital in each producer country for positive and finite values of capital productivity and capital frictions. Fifth, it matches limited capital flows from rich to poor countries (e.g. Lucas 1990), because capital is imperfectly substitutable across countries, and even if poor countries offer higher rental rates, they can have lower capital productivity or higher capital frictions.

The implications for responses to productivity shocks

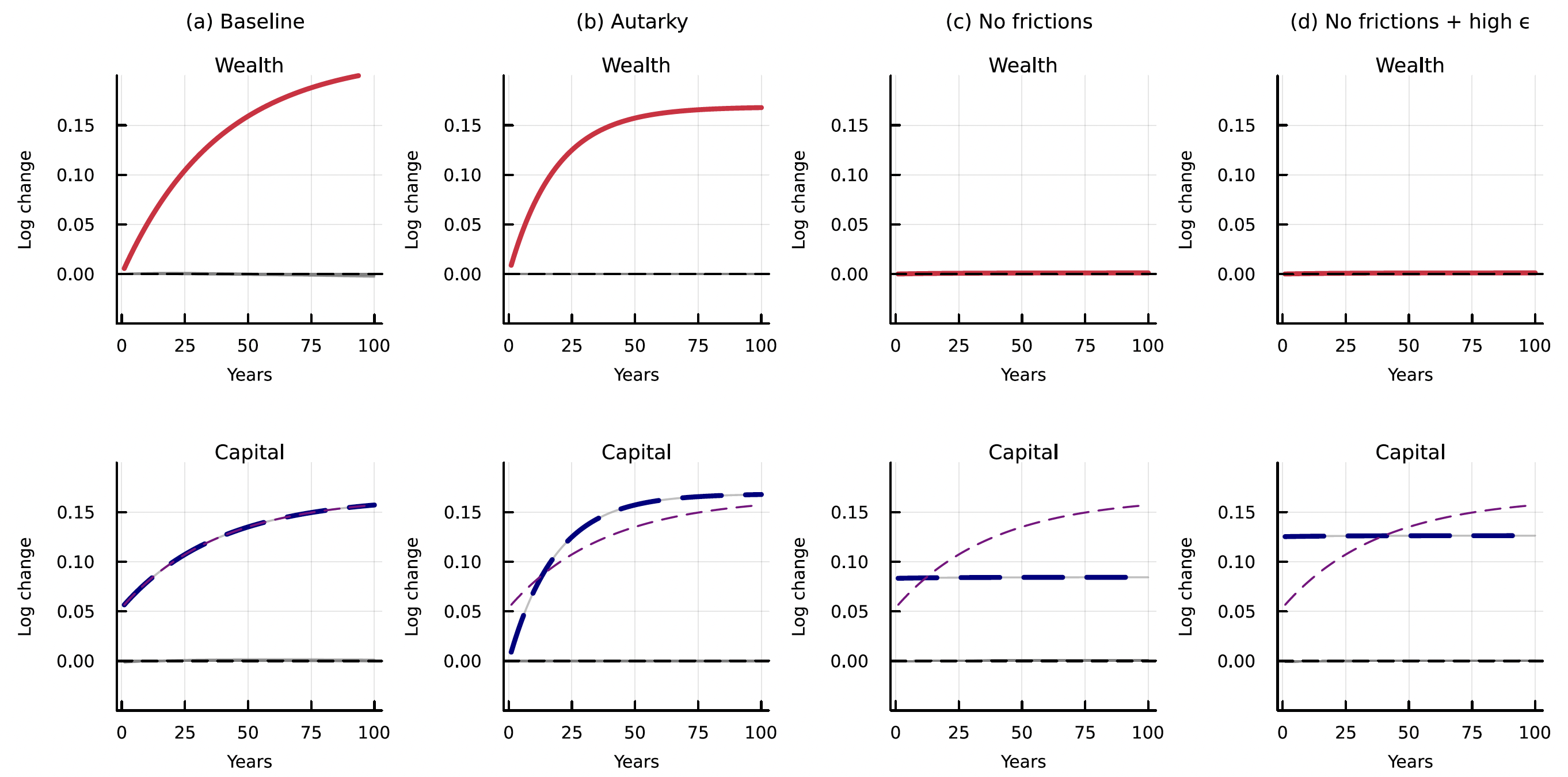

Incorporating imperfect substitutability and goods and capital market frictions yields new insights for impulse responses to productivity shocks and the speed of convergence to steady-state. In the CNGM, the higher steady-state capital stock implied by a positive productivity shock only can be achieved through domestic wealth accumulation (see panel b of Figure 1). In contrast, in the conventional open-economy neoclassical growth model, a positive productivity shock induces an immediate reallocation of capital that equalises the rental rate on capital across all countries (see panels c and d of Figure 1). Our framework generates predictions in between these two extremes (see panel a of Figure 1). The higher steady-state capital stock implied by a positive productivity shock is achieved through a combination of both domestic wealth accumulation and international capital reallocation. This initial reallocation of capital dampens the variation in the real return to investment across countries in response to the productivity shock, thereby implying slower convergence to steady-state.

Rationalising slower income convergence

Our open-economy framework thus provides a natural explanation for the finding that empirical estimates of income convergence imply longer transitions than predicted by the CNGM for plausible intertemporal elasticities of substitution (e.g. King and Rebelo 1991, Barro et al. 1995). The magnitude of this initial reallocation of capital depends on the degree to which capital is imperfectly substitutable across countries. In the presence of goods and capital market frictions, the real return to investment differs across countries along the transition path to steady-state, such that some countries accumulate wealth more rapidly than others.

Figure 1 Small country productivity shock

Note: Impulse responses to a 10% productivity shock in a small country (Belgium) for our baseline parameter values; first panel from the left (panel (a)) shows impulse responses in our baseline model with costly trade and capital flows and imperfect substitutability; second panel from the left (panel (b)) shows impulse responses in the CNGM; third panel from the left (panel (c)) shows impulse responses with no trade and capital market frictions and imperfect substitutability; fourth panel from the left (panel (d)) shows impulse responses with no trade and capital market frictions and imperfect substitutability in goods markets but a perfectly elastic supply of capital (ϵ→∞); the red line in the top row shows impulse responses for wealth in Belgium; the dashed blue line in the bottom row shows impulse responses for capital in Belgium; the purple dashed line in the bottom row reproduces the impulse responses for capital in Belgium for our baseline model (panel (a)) in all other panels for ease of comparison.

We show that goods and capital market integration interact in non-trivial ways to shape the speed of convergence towards steady-state. In the CNGM, the speed of convergence is determined by the degree of diminishing returns to capital accumulation. Opening the CNGM to only free trade in goods raises the speed of convergence, because each country's good now faces substitutes in world markets. Therefore, increases in output of a country's good lead to larger falls in its price than in the closed economy, which implies a more rapid decline in the real return to investment. Opening the CNGM to only free capital flows also raises the speed of convergence to steady-state, because each country now competes to attract capital in world markets. Therefore, attracting additional capital to produce more output requires a larger rise in the rental rate than in the closed economy, which again implies a more rapid decline in the real return to investment. In contrast, opening the CNGM to both free trade and free capital slows the speed of convergence. The reason is that the opening of trade and capital flows leads to an initial reallocation of capital that equalises the real return to investment across all countries. After this initial reallocation, there is no correlation between the real return to investment and initial levels of wealth or capital, which implies slower convergence than in the closed economy. All countries accumulate wealth at the same rate, as determined by this common real return to investment, and initial differences in wealth persist forever.

Stimulating the effect of disintegration

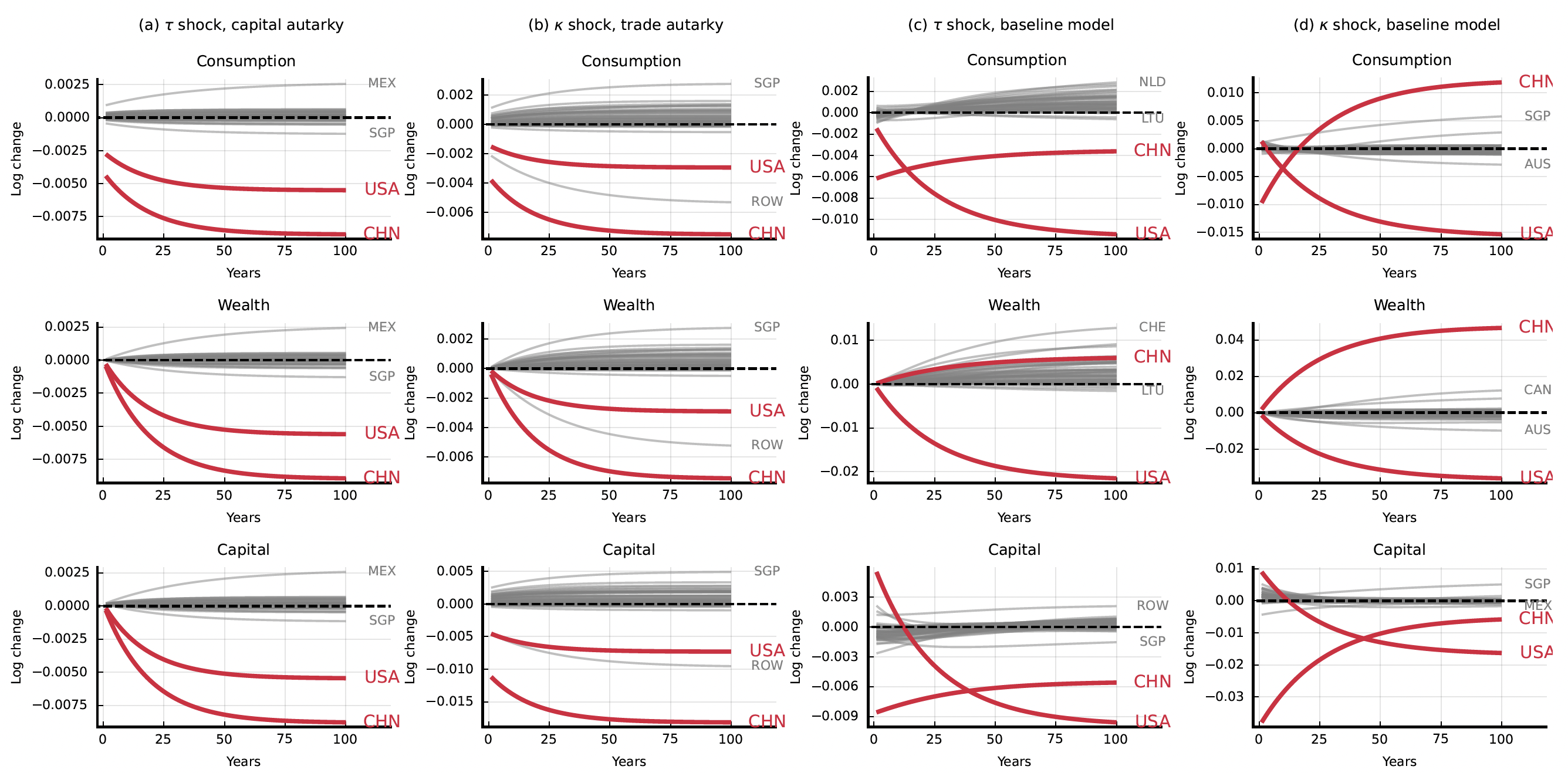

We use our framework to evaluate the impact of counterfactual policies that inherently involve disintegration in both goods and capital markets, such as a decoupling of China and the US. In Figure 2, we show the results of four counterfactuals: (1) higher bilateral trade frictions with open goods markets and capital autarky (panel a); (2) higher bilateral capital frictions with trade autarky and open capital markets (panel b); (3) higher bilateral trade frictions with open goods and capital markets (panel c); and (4) higher bilateral capital frictions with open goods and capital markets (panel d). In each panel, we show the transition path for consumption in the top row, the transition path for the wealth state variables in the middle row, and the transition path for capital in the bottom row. We show results for China and the US by the solid red lines labelled with three-letter international standards organisation (ISO) country codes (CHN and USA); we show results for all other countries by the solid grey lines; we label the results for the other countries characterised by the largest and smallest changes in a variable with three-letter ISO country codes.

Figure 2 Counterfactuals for an increase in bilateral US-China trade and capital frictions

Note: Counterfactuals for permanent increase in bilateral frictions between China and the US at time t = 1. The first and the third columns show counterfactuals for 50% increase in trade frictions (τ shock), and the second and fourth columns show counterfactuals for 50% increase in capital frictions (κ shock). The first column considers the special case of the model with international trade but no international capital flows; the second column considers the special case of the model with international capital flows but no international trade; and the last two columns consider our baseline model with both trade and capital flows. Each row shows log deviations from the initial steady-state: the first row shows these deviations for consumption; the second row shows these deviations for wealth; and the bottom row shows these log deviations for capital.

With open goods and capital markets (panel c), higher US-China trade frictions again lead to an initial drop in consumption in both countries from foregone static welfare gains from trade (top row). As for changes in bilateral trade frictions under capital autarky (panel a), the initial decline in consumption is larger for China than for the US, because the US is a more central market for China’s exports than China is for the US. However, with open capital markets, changes in bilateral trade frictions now lead to initial reallocation of capital across countries. In particular, China becomes relatively less attractive for capital holdings, because of the decline in demand for its output in US markets, while the US becomes more attractive for capital holdings, as it substitutes away from consumption of Chinese goods towards local production. As a result, there is an initial reallocation of capital from China and some third countries towards the US (bottom row).

In addition to these static welfare effects, higher US-China trade frictions also affect the real return to investment, which has dynamic welfare effects through the accumulation of wealth and capital. Here again we find a starkly different pattern of results in our model (panel c) from under capital autarky (panel a). With open goods and capital markets, the impact on China’s real return to investment depends not only on the deterioration in local capital market conditions, but also on the improvement in investment opportunities in other countries. Moreover, the reduction in demand for its goods in the US market lowers China’s consumption price index, leading to a cheaper cost of investment goods. Consequentially, its real return on investment rises, which leads to mild accumulation of wealth over time. In contrast, the US experiences an increase in its consumption price index and the cost of investment goods, and a decline in the return to investment in one of its major investment destinations (China), leading to a decumulation of wealth.

Comparing consumption in China and US in the new steady-state (top row), we find a reversal of fortune between China and the US over time in our model (panel c), with China losing more consumption in the short run, whereas the US loses more consumption in the long run. This is in contrast to the case of capital autarky and open goods markets (panel a), in which the greater reduction in China’s consumption persists over time. Therefore, we find that the effects of changes in goods market integration depend heavily on the degree of capital market integration, emphasising the importance of studying these two dimensions of international integration in tandem.

We find a similar pattern for increases in capital market frictions in panels (b) and (d). An increase in US-China capital market frictions increases the real return to investment in China, because of the decline in the supply of capital from the US. In contrast, the real return to investment in the US decreases, because of the reallocation of capital previously invested in China back to the home market. Both effects follow from the position of the US as a major supplier of capital to China. As a result, China accumulates wealth (middle row), and its consumption gradually increases over time (top row), whereas the opposite occurs in the US. Moreover, since with open goods and capital markets the US specialises in exporting capital services, it is more sensitive to rising frictions in capital markets, with this negative income effect further lowering the real return to investment and inducing the decumulation of wealth.

Comparing consumption in China and US in the new steady-state (upper row), we again find a reversal of fortune. Whereas China is more adversely affected than the US in the short run, it is less adversely affected (and even gains) in the long run in our model (panel d). This is in contrast to the case of goods autarky (panel b), in which the adverse effect on China relative to the US persists over time. Therefore, we find that the effects of changes in capital market integration also depend heavily on the level of goods market integration, further highlighting the importance of simultaneously modelling both these dimensions of international integration.

References

Angeletos, G-M (2007), “Uninsured Idiosyncratic Investment Risk and Aggregate Saving,” Review of Economic Dynamics 10: 1-30.

Barro, R, N G Mankiw and X Sala-i Martin (1995), “Capital Mobility in Neoclassical Models of Growth,” American Economic Review 85: 103-115.

Feldstein, M and C Horioka (1980), “Domestic Saving and International Capital Flows,” Economic Journal 90: 314-29.

French, K R and J Poterba (1991), “Investor Diversification and International Equity Markets,” American Economic Review 81: 222-226.

King, R G and S T Rebelo (1993), “Transitional Dynamics and Economic Growth in the Neoclassical Model,” American Economic Review 83: 908-931.

Kleinman, B, E Liu, S J Redding and M Yogo (2023), “Neoclassical Growth in an Interdependent World,” NBER Working Paper 31951.

Lucas, R E (1990), “Why Doesn’t Capital Flow from Rich to Poor Countries,” American Economic Review 80: 92-96.

Moll (2014), “Productivity Losses from Financial Frictions: Can Self-Financing Undo Capital Misallocation,” American Economic Review 104: 3186-3221.

Obstfeld, M and K Rogoff (2000), “The Six Major Puzzles in International Macroeconomics: Is There a Common Cause?”, NBER Macroeconomics Annual 15: 339-390.

Portes, R and H Rey (2005), “The Determinants of Cross-Border Equity Flows,” Journal of International Economics 65: 269-296.

Solow, R M (1956), “A Contribution to the Theory of Economic Growth,” Quarterly Journal of Economics 70: 65-94.

Swan, T (1956), “Economic Growth and Capital Accumulation,” Economic Record 32: 344-61.