Problems of demography and health put the US is in a precarious position. Growing health spending on the ageing baby-boom cohort have driven public resources to the edge of a demographic cliff. The US is also being forced to confront the disparities in health spending and outcomes, and the racial and educational inequality that underlies them.

The end of the demographic dividend

Like most high-income countries, the US has a rapidly ageing population and a potential decline in labour force numbers (United Nations 2017).

Driven largely by changing birth rates, the US population’s age structure has changed dramatically since the end of WWII. After the end of the war, birth rates rocketed from about two per woman in the pre-war years to 3.7 in the 1950s (the 'baby boom'). Birth rates did not return to pre-war levels until the mid-1960s.

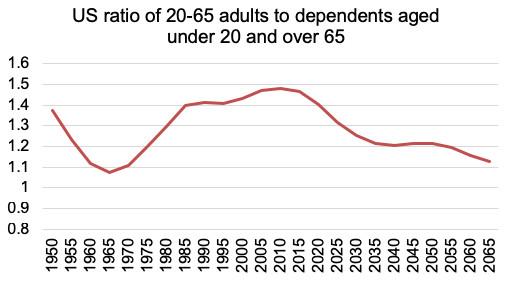

Fuelled by the growing number of babies and young children, the ratio of working-age adults (20–64 years of age) to young (under 20) and elderly (65 and over) dependents changed too, falling steadily from the 1950s through the early 1970s. The ratio started to climb again in the 1970s and 1980s, when boomers entered young adulthood, fertility declined, and many working-age adults immigrated to the US.

When adults in the prime years for earning and saving increasingly outnumber dependents, a country realises a demographic growth dividend. The US saw this from this bulge of young and middle-aged adults. Of course, there are also financially productive individuals under the age of 20 and over the age of 65, but these cut-offs help to broadly characterise economic activity.

At its peak in 2010, there were 1.48 working-age adults to each dependent in the US. This ratio is projected to drop rapidly, falling to 1.13 by 2065 – the lowest it will have been since the 1960s. Unlike in the 1960s, however, the democratic cliff will not be created by a rising population of young dependents. Rather, the population of older dependents will grow as the baby boomers retire while fertility rates remain below the long-term replacement rate of 2.1 births per woman.

Thanks to fertility being close to 2.1, to working-age immigration, the drop in this ratio will not be as dramatic as in other OECD economies. For example, the rations of working-age citizens to dependents in Japan, South Korea, and Spain are expected dip below one by 2065. But the US demographic dividend is over.

Figure 1 Changes in working age ratio since the 1950s and projected ratio up to 2065

Government benefits to retirees, in the form of both cash and medical care, are some of the most important channels through which an ageing population stresses an economy. The reason is the pay-as-you-go nature of the American social security system, in which a relatively small generation of current payroll taxes finance pensions for a growing number of beneficiaries (as in several European economies).

Americans are eligible to receive government retirement benefits beginning at age 62. In 2011, social security officials estimated that, by 2036, these benefits will need to be cut to about 75% of current levels. As in most of the world, US life expectancy is growing. In the 1950s, a 65-year-old American could, on average, expect to live another 14 years. Today, life expectancy at 65 is almost 20 years. In 40 years from now, someone reaching the age of 65 would expect to live about 24 more years.

If it does not reform the pension system drastically, the US government must prepare to support more retirees for more years on smaller revenues. It will most likely do this using a combination of payroll tax increases, reduced benefits, or raising the age of eligibility. These changes will have a disproportionately large impact on low- and middle-income Americans, who depend the most on government transfers for support in their old age – particularly people in manual, low- or medium-skilled jobs, who already have shorter working lives and more health problems due to the physical nature of their work.

Health spending in the US and abroad

The past 100 years brought improvements in public health, rising longevity and falling mortality rates in both high-income and low-income countries. The US has been no exception.

But a closer look reveals disturbing disparities and inequities, both between the US and other nations, and between different groups in the country.

In the aggregate, US life expectancies are increasing at all age levels. But this conceals disparities between sexes, and among races and ethnicities. As almost everywhere, on average women live longer than men. In the US, however, life expectancy for black men and women has lagged that of white men and women due to many factors, including differences in income and health insurance coverage, differences in education and related health-seeking behaviour. Also, unlike most other wealthy countries, the US does not have a system of nationalised medicine, and so there are also differences in their access to medical care.

This gap has narrowed over recent decades – according to the US Centers for Disease Control (CDC), in 1960, average white life expectancy at birth was 70 years, six years longer than black life expectancy. By 2015, this gap had shrunk to four years (79 years for whites and 75 years for blacks). The US government also separates out Asian Americans, Native Americans, and Hispanic Americans for the purposes of data collection, but only started to do so in the 1980s.

Despite this progress, the US lags its peers, especially considering total health spending. According to the World Health Organisation, current annual public and private health expenditure in the US, at $9,536 per capita, is second only to Switzerland's $9,818.

The relationship between health inputs in dollars, and health outcomes in mortality indicators, is not straightforward. Among many complex reasons, the US health system is so expensive because it is weighted toward specialist physicians who provide costly, high-tech procedures such as MRI scans and caesarean sections. Also, the opaque and complicated pricing systems that private health insurance plans offer make it difficult to shop around for cheaper healthcare. Social and economic inequality also drive up health spending (for example, by leading to more low birthweight babies who require costly care).

It is nonetheless worth noting that many US health indicators are no better than those of countries whose health spending is much lower. For example, the US has a low level of infant mortality – five infant deaths per 1,000 live births. But so do Slovakia, which spends $1,772 per capita on health, and Malaysia, which spends just $377. An American baby has a life expectancy of about 80 years, the same as Lebanese ($645) and Costa Rican ($929) newborns.

Maternal mortality rates

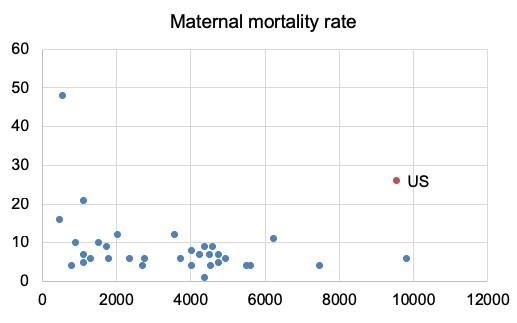

The maternal mortality rate is one of the US health system’s most startling problems (Figure 2). In 2015, 26 American mothers died from pregnancy- or delivery-related health problems, including haemorrhage, infection, maternal hypertensive disorders, and post-partum depression, for every 100,000 live births. Among the 34 high-income OECD nations, maternal mortality is higher only in Mexico, which spends 6% of what the US does on health.

Other US health indicators have improved over time, but its maternal mortality rates have actually got worse. The CDC began tracking these deaths in the 1980s, and they have risen steadily since then. Rising rates of chronic conditions such as heart disease and diabetes are possible reasons because they make pregnancy complications more likely, as well as medical care that puts more emphasis on the needs of babies than mothers.

Figure 2 Scatterplot of maternal mortality rates and current health spending among OECD countries

Data sources: World Health Organisation and The Lancet

The high rates of maternal mortality in the US are bad enough. But, once again, the statistics are even more disturbing if we disaggregate them. Mothers of all ages, income levels, and races may die in or after childbirth, but black women are three to four times more likely to die of these causes than white women. The CDC indicates that, between 2011 and 2014, black women suffered from maternal mortality at a rate of 40 per 100,000 live births. This is higher than the average in Egypt (33) and Georgia (36), countries with GDP per capita that year that were approximately 95% lower than the US. In 2014, the maternal mortality rate for white women in the US was 13, and the rate for women of other races was 14. The infant mortality rate for black babies is also twice that of white babies.

We might expect that as our levels of income and education improve, we all get higher-quality medical care, have a healthier lifestyle and better health-seeking behaviour, and thus our health outcomes are better overall. This appears not to be true in the case of black maternal deaths. For example, black college-educated women giving birth in New York City hospitals between 2008 and 2012 were more likely to suffer from serious health complications related to pregnancy and childbirth than white women with less than a high school diploma.

Racial disparities in maternal mortality may be caused by the bias of healthcare providers, who are less likely to take black women’s concerns and complaints seriously. In 2017, the experience of tennis superstar Serena Williams vividly illustrated this problem. She suffered severe complications following the birth of her daughter. According to Williams, these complications were mad worse because hospital staff did not listen to her requests for specific medication and procedures that were related to her history of blood clots. She had to undergo emergency surgery, and was confined to bed for six weeks afterwards.

Deaths of despair

Aggregate US life expectancy figures only tell part of the story of health and demographics. Differences in income and social class also matter. Although black Americans suffer from discrimination and historical disadvantage, life circumstances for some white Americans are becoming dramatically worse.

Based on extensive analysis of CDC data, Case and Deaton (2017) conclude that mortality levels for middle-aged, non-Hispanic whites with a high school education or less have been increasing since the 1990s (the US government treats 'Hispanic origin' an identifier for people with roots in countries with Spanish-speaking cultures, as a distinct category – an Hispanic person may be of any racial group).

This trend contrasts starkly with all other racial groups and education levels, for which mortality rates in middle age have steadily decreased during this period. Case and Deaton attribute this in part to a slowdown, though not a halt, in the decline in mortality due to heart disease and cancer. But the authors also point to a rise in what they call “deaths of despair” – deaths due to suicide, alcohol, and drugs – in this group. The current opioid epidemic, in which the number of annual overdose deaths increased almost six-fold between 1999 and 2017, has intensified the rate of these deaths of despair.

There are no simple explanations, but the authors suggest that these Americans have fewer job opportunities, lower rates of marriage and the stability it confers, and less support from community institutions such as churches, transmitted from generation to generation in a process of “cumulative disadvantage.” This has leads to higher levels of depression and substance abuse.

Compared to other wealthy countries, the US lacks a strong social safety net and mechanisms for wealth distribution. As a result, the factors that Case and Deaton identify have a comparatively greater effect on wellbeing. They warn that the trend of rising mortality among the least-educated white Americans “[w]ill not easily or quickly be reversed by policy … nor can those in midlife today be expected to do as well after age 65 as the current elderly.”

Beyond the edge

Quick, easy policy changes will not solve the problems of population ageing, high healthcare costs, and high inequality in maternal mortality and other health indicators in the US. Government and policymakers will likely need to address these challenges through large-scale social policy and health system reform. This will include a wider social safety net and better education for medical professionals, particularly about risk factors for expectant mothers and unconscious bias against historically marginalised populations, such as black women. A shrinking working population could also be supplemented by increased immigration of working-age adults to the US.

But, in the current political climate, these reforms may not be feasible in the near future.

Authors’ note: This work was supported by a grant from Carnegie Corporation of New York. The statements made and views expressed are solely the responsibility of the authors.

References

Case, A, and A Deaton (2017), "Mortality and morbidity in the 21st century", Brookings Papers on Economic Activity, Spring: 397-476.

United Nations (2017), World Population Prospects: The 2017 Revision.