How effective is monetary policy in stabilising inflation and economic activity? The answer to this classic question is fundamentally linked to the flexibility of the aggregate price level. When the price level is flexible, inflation dynamically adjusts to policy changes. Conversely, when it is sticky, economic activity adjusts instead. The frequency with which prices change serves as a crucial determinant of price flexibility. This frequency demonstrates remarkable stability over time, and variations across countries and sectors reliably predict price responsiveness to policy changes (Hong et al. 2023). Consequently, scholars and policymakers have heavily depended on time-dependent price-setting frameworks, where the frequency remains constant. However, the recent surge in inflation provides compelling evidence that, following significant disturbances, the frequency of price adjustments is not constant (Montag-Villar 2023). In essence, price setting is state-dependent, not time-dependent.

In state-dependent price-setting frameworks, the frequency of price changes alone is not a reliable predictor of price flexibility. A price level can remain flexible even if only a handful of prices adjust, provided that the prices which do change do so disproportionately. This phenomenon may arise when firms prioritise adjusting the most misaligned prices to economise on the associated costs of adjustment (such as managerial time, as suggested by Zbaracki et al. 2004). The selection of large price changes has been identified as potentially being as significant a determinant of price-level flexibility as the frequency of price changes (Golosov and Lucas 2007, Le Bihan et al. 2014). Consequently, empirically estimating the extent of this selection is crucial for an accurate evaluation of price flexibility and the effectiveness of monetary policy.

In recent research (Karadi et al, 2023), we employed a novel supermarket price dataset from four European countries, together with a comparable dataset from the US, to measure the extent of selection in both regions. The European dataset, sourced from the marketing firm IRi, was procured by the European Central Bank as part of the Price-setting Microdata Analysis Network (PRISMA). This dataset encompasses data from Germany, the Netherlands, France, and Italy spanning the years 2013 to 2017. It documents weekly prices of over two million products across more than 37,000 stores in a geographically representative sample. For comparison, we utilised the US IRi Academic Dataset, an analogous weekly panel covering the timeframe 2001-2012, which records prices for over 200,000 products in more than 3,000 stores, representing the 50 most significant US markets.

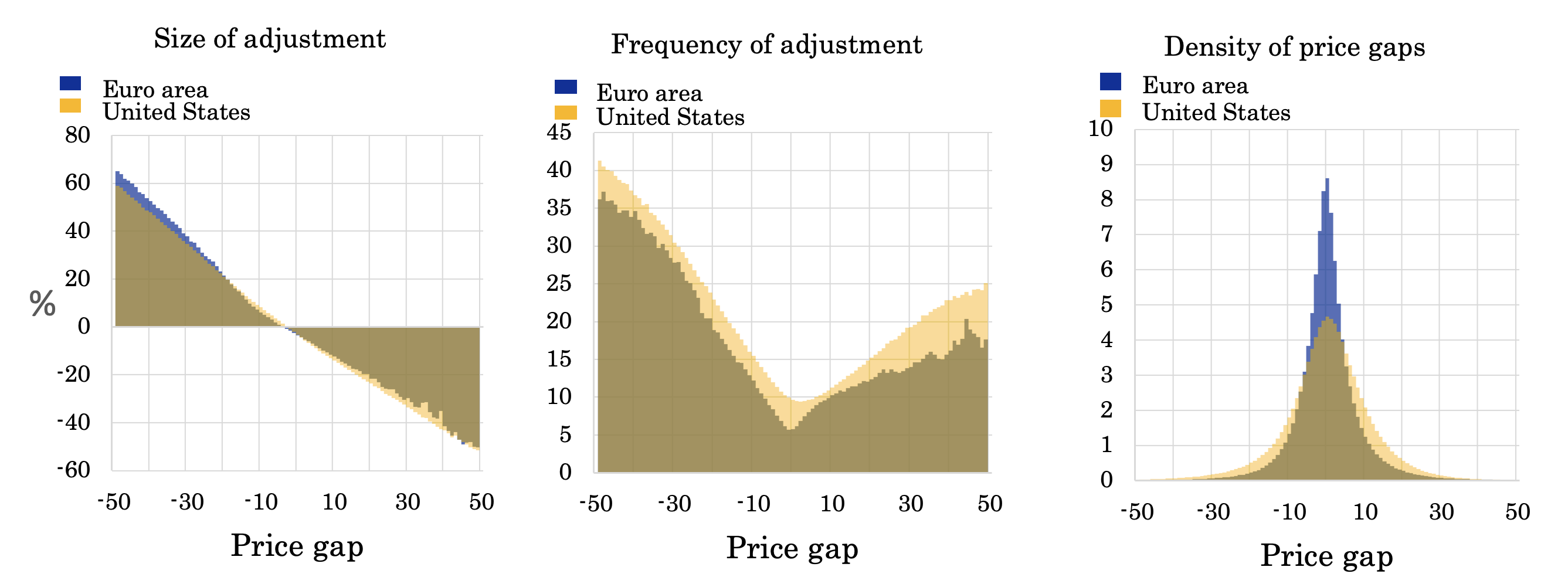

The unmatched cross-sectional granularity of the data enables us to derive data moments indicative of the degree of price selection. The primary empirical challenge lies in quantifying the price misalignment or the 'price gap', which denotes the deviation of a price from its unobserved optimal level. To proxy this optimal price, we utilise the average price of the identical product in competitor stores that adjusted their prices within the same month. This measure also accounts for permanent differences in store- and category-level prices resulting from variances in amenities, geographic location, or market power. The first panel of Figure 1 illustrates the relationship between the average magnitude of (non-zero) forthcoming price changes and our price gap metric. The exceptionally close, nearly one-to-one inverse relationship with the price gap in both regions indicates that supermarkets, on average, close this gap when they modify their prices, thus validating our misalignment proxy.

Figure 1 Size and probability of price adjustment as a function of the price gap and its density

Armed with this valid proxy, we proceed to evaluate the presence of selection in the dataset. The second panel of Figure 1 depicts the relationship between the price gap and the likelihood of a price adjustment: termed as the 'price-adjustment hazard'. The V-shaped curve observed in both regions serves as direct evidence of selection in price setting: prices that are more misaligned are adjusted with a higher probability. The frequency of price changes in the US consistently surpasses that in the euro area, pointing to more frequent price changes in the former.

The third panel of Figure 1 presents the distribution of the price gaps. These gaps are dispersed in both territories, with a more pronounced dispersion in the US compared to the euro area.

The hazard function and the price-gap density are sufficient statistics to quantify the contribution of selection to price flexibility (Caballero and Engel 2007). The selection effect measures how prices that deviate further from their optimum adjust with higher probability when there's an easing of aggregate monetary policy. Such easing elevates optimal prices, uniformly decreasing the price gaps and, thereby, shifting the price gap density to the left. The composition of those who adjust is influenced by the hazard function's slope, which indicates how the likelihood of adjustment changes for each gap after a policy shock. The product of this slope and the price gap, integrated over the gap distribution, determines selection. High gaps among new adjusters imply strong selection. Beyond selection, the aggregate price level's flexibility is also influenced by the frequency of price adjustments through an intensive-margin effect. Prices, which would have been adjusted even without the shock, undergo larger changes due to the aggregate shock's impact.

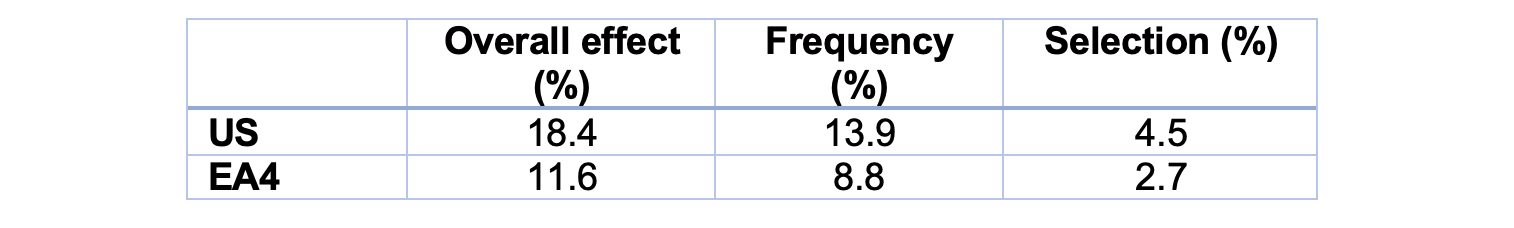

Table 1 presents quantitative assessments of price flexibility (overall effect) alongside the impacts of both frequency and selection effects. Selection increases price flexibility by approximately a third in both regions, suggesting that relying solely on frequency underrepresents true price flexibility. The table also reveals that price flexibility is more pronounced in the US, attributable to both its greater frequency and stronger selection. The primary reason for the higher selection in the US is the more extensive dispersion of price gaps, as illustrated in the right panel of Figure 1, while the hazard slopes remain relatively consistent.

Table 1 Impact effect and contributions of frequency and selection effects

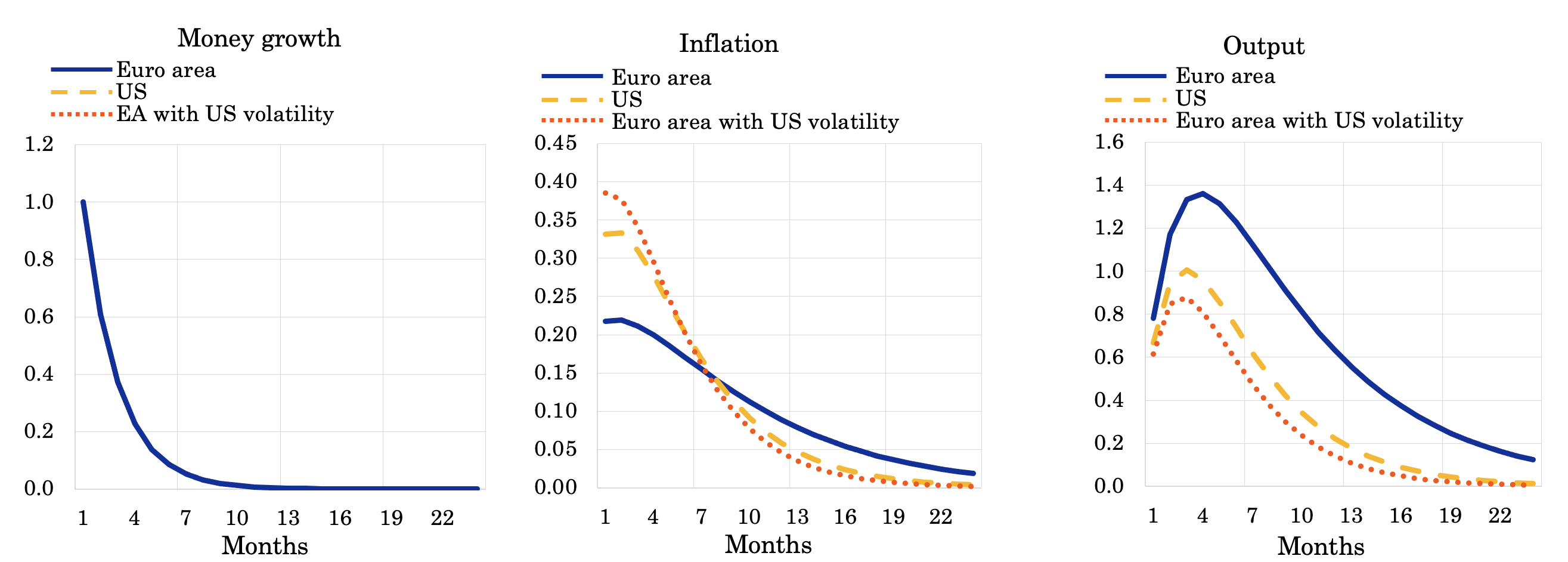

A price-setting model (Woodford 2009), calibrated to match the hazard and density observed in the data, can simulate responses to an aggregate shock. Such a shock might arise from a monetary policy easing or an event like the Covid-19 pandemic, which raised supermarket demand due to widespread restaurant and café lockdowns. The outcomes of these simulations are depicted in Figure 2. Consistent with the findings in Table 1, the data illustrate that, in the US, inflation adjusts more flexibly while output reactions tend to be more muted in response to shocks of comparable magnitude. This is in line with the more elevated food inflation observed in the US during the initial year of the pandemic.

Figure 2 Simulated response to a monetary policy change

The model can also assess the fundamental factors contributing to the differences between regions. It finds that the strength of price-adjustment frictions remains broadly similar in the two regions. The primary determinant leading to a higher frequency and more potent selection is the increased cross-sectional volatility found in the US. Heightened fluctuations at the product level—whether caused by more frequent cost innovations or more potent demand swings—compel retailers to change prices more often and amplifies price misalignments, subsequently boosting the selection of large price changes. The dotted red line presented in Figure 2 corroborates the finding that if the euro area counterfactually exhibited product-level volatility equal to that in the US, their price flexibilities would be similar in the two regions. Its key role in driving regional disparities also highlights the importance of further research into product-level volatility and its underlying sources.

Authors’ Note: All opinions expressed are personal and do not necessarily represent the views of the European Central Bank, the Eurosystem, or the OECD.

References

Caballero, R J and E M R A Engel (2007), “Price Stickiness in Ss Models: New Interpretation of Old Results”, Journal of Monetary Economics 54(S): 100-121.

Calvo, G A (1983), "Staggered Prices in a Utility-Maximizing Framework", Journal of Monetary Economics 12(3): 383–398.

Golosov, M and R E Lucas (2007), "Menu Costs and Phillips Curves", Journal of Political Economy 115(2): 171–199.

Hong, G H, M Klepacz, E Pasten and R Schoenle (2023), “The Real Effects of Monetary Shocks: Evidence from Micro Pricing Moments”, Journal of Monetary Economics, forthcoming.

Karadi, P, J Amann, J S Bachiller, P Seiler and J Wursten (2023), “Price Setting on the Two Sides of the Atlantic – Evidence from Supermarket Scanner Data”, Journal of Monetary Economics, forthcoming

Le Bihan, H, F Lippi and F Alvarez (2014), “Modelling sticky prices and the effect of monetary shocks", VoxEU.org, 30 September.

Montag, H and D Villar (2023), “Price-Setting During the Covid Era”, FEDS Notes, 29 August.

Woodford, M (2009), “Information-Constrained State-Dependent Pricing”, Journal of Monetary Economics 56: S100-S124.

Zbaracki, M J, M Ritson, D Levy, S Dutta and M Bergen (2004), “Managerial and Customer Costs of Price Adjustment: Direct Evidence from Industrial Markets”, Review of Economics and Statistics 86(2): 514-533.