A wide and growing majority of people worldwide recognise the existential threat of climate change and the need for a green transition.

Paradoxically though, specific policy proposals (especially when coming from economists) have a hard time obtaining popular support (see, for example, Gollier and Tirole 2015). While this could of course be partly due to the well-known ‘not in my backyard’ (NIMBY) attitude, the utopia of a happy and sacrifice-free transition, and free-rider incentives, there are other salient reasons. A new CEPR eBook (Gollier and Rohner 2023) features contributions from leading economists and practitioners who provide a comprehensive overview of the challenges, initiatives, and far-reaching impacts of ‘going green’.

Communicating successfully that well-designed green taxes are fair and redistributive

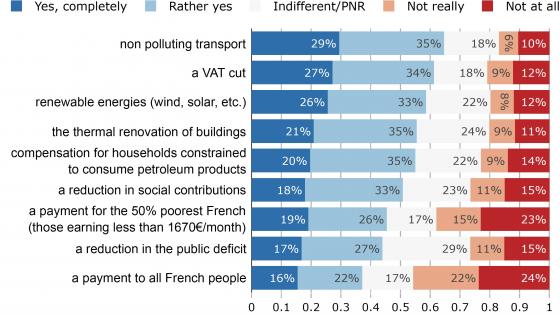

First, communicating green policies based on monetary incentives has proven very challenging. In particular, as documented for example by Douenne and Fabre (2020), green taxes are often criticised as regressive (i.e. increasing inequality). Strikingly though, clever design of a given levy can ensure that poorer households face less of a fiscal burden and/or receive a greater share of the fiscal revenues. Thus, a carbon tax with a targeted redistribution of the ‘carbon dividend’ is actually able to fight climate change and inequality, without raising the tax burden. The tricky part is of course communication (Dechezlepretre et al. 2022, Ewald et al. 2022). It is not easy – yet it is crucial – to inform households in an easily understandable way that the environmentally conscious among them may actually get back much more in return than they contribute under a newly introduced green tax. The only ‘losers’ would be households that are well-off and that pollute disproportionally; all other households may be on the receiving end overall.

When it comes to the international sharing of the cost of the green transition, it is again crucial that any solutions proposed are perceived as fair, even if this may at times come at the cost of efficiency. The current climate crisis has been caused by reckless and irresponsible behaviour by the rich world, and bullying the current or future generations of poor nations into bearing the costs of this would be morally repellent. On top of this, if rich democracies are seen as phony and selfish, their political clout will further decline – and we are moving closer to a world of ruthless autocratic great powers imposing their will on smaller countries in their supposed sphere of influence. A key aspect of convincing countries around the world of the merits of a rules-based order is displaying solidarity and generosity in situations of crisis, whether during pandemics or in the realm of climate change. Up to now, the track record of the rich democracies in that respect has been far from stellar, to say the least.

Avoiding price spikes that provide ammunition for populists

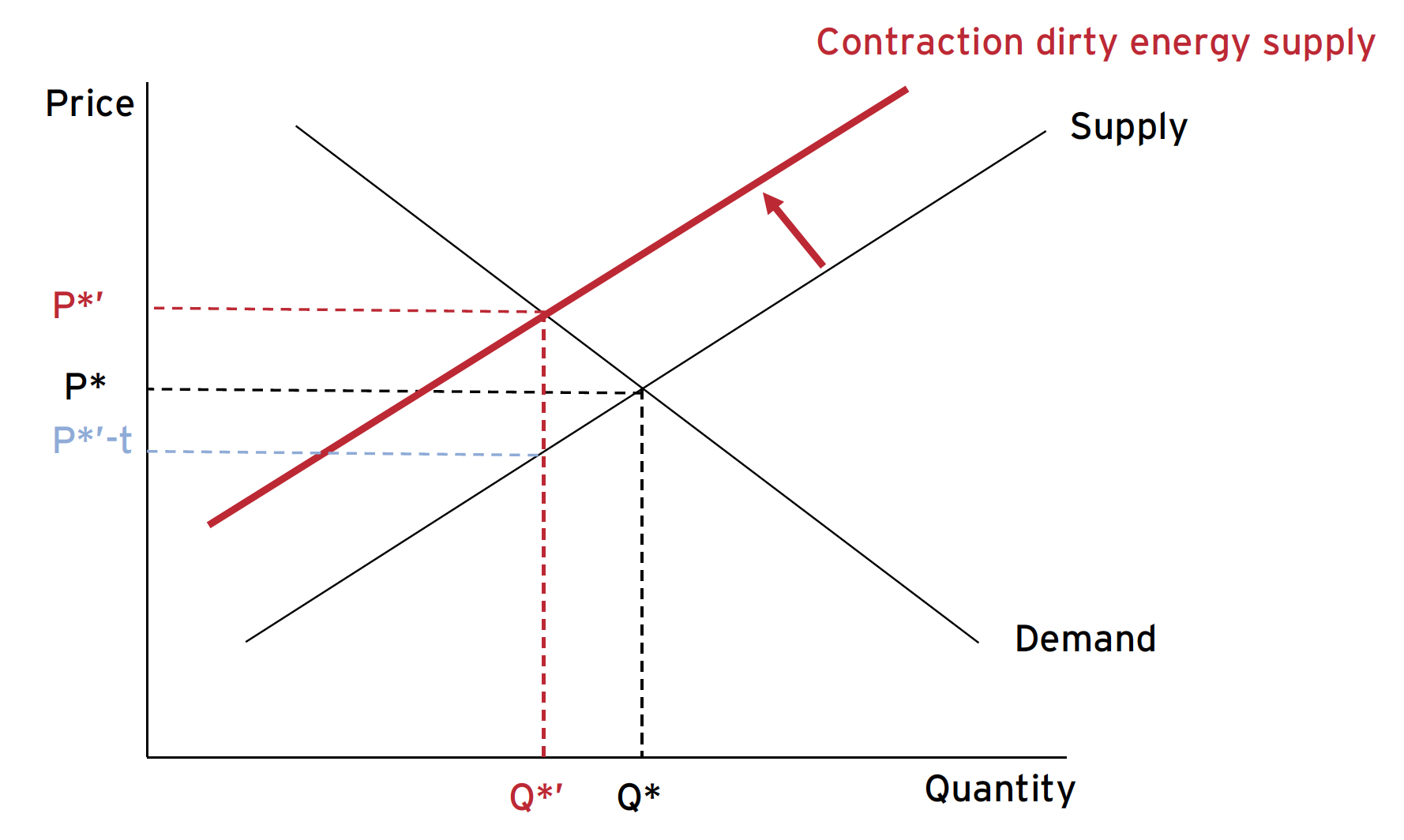

If climate action is very narrowly geared towards, say, reducing ‘dirty’ energy consumption by starting with bans of fossil fuels supply without tackling excess demand for energy, this can have side effects that constitute a jackpot for cynical yet cunning populists. As shown in Figure 1, when policies focus solely on a rapid ban of dirty energy production (Panel A), the demand curve will not move while the supply curve will shift to the left. While this entails the desired reduction in the quantity of energy used, this supply-side climate policy also leads to a price spike (from P* to P*’), as observed for example during the recent energy crisis in Europe. This price spike can be exploited by populist parties that are against green policies. Accusing green measures of raising price levels is trick 101 in the populists’ playbook when fishing for votes among the disenchanted. To avoid a backlash against the green transition, it is better to have a more balanced approach that reduces energy supply from fossil fuels and at the same time aims at reducing energy demand. There are two strategies to attain this objective.

The easiest solution is the one promoted by a vast majority of economists since Pigou (1920). Rather than imposing a reduction of supply from Q* to Q*’ on the oil majors, let the government impose a carbon tax, t. The new market equilibrium also generates the same increase in consumer price to P*’, and therefore the same reduction in consumption to Q*’. Yet, the price received by the producers is lower, as it is limited to P*’-t (displayed in blue in panel A of Figure 1) – where the difference between consumer and producer prices corresponds to the tax t. This carbon pricing approach yields exactly the same environmental outcome and the same consumer loss as the supply-side policy presented above, but it differs with respect to the way in which the oil rent is redistributed. The carbon pricing policy has the advantage that it transfers the oil rent t(Q*-Q*’) from the shareholders of the brown industries to the coffers of the state, which can use it to compensate vulnerable consumers. It is a mystery why economists have struggled to convince a solid majority of climate activists and the population at large to support carbon pricing – a policy which unambiguously dominates the aforementioned supply-side policy.

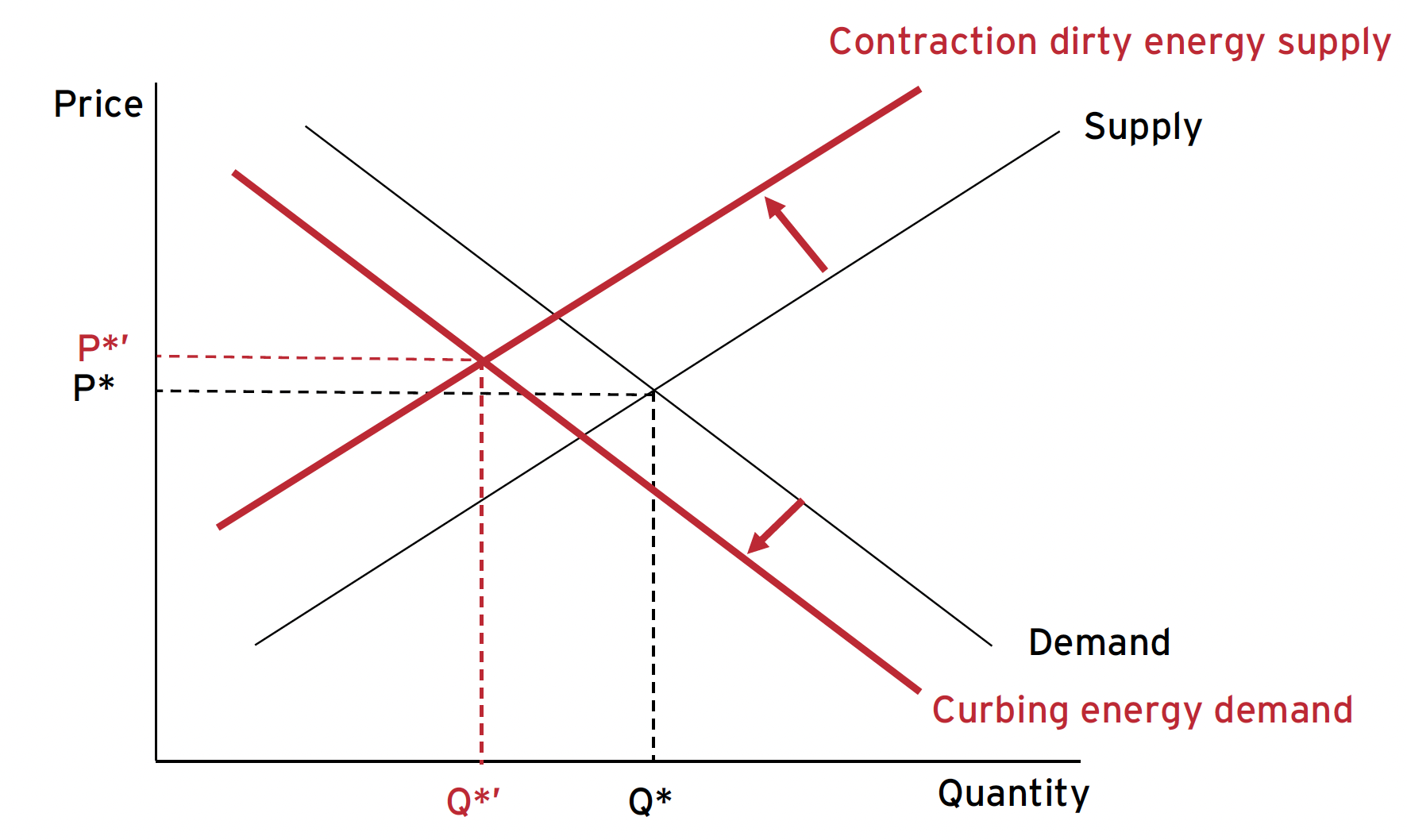

The alternative method to carbon pricing is to combine a ‘sobriety’ policy on the demand side with the original supply-side policy (as displayed in Panel B). Concretely, supply-side measures (such as closing gas power plants) should be combined with demand-side measures (subsidising envelope renovations, communication fostering sobriety, etc). In this way not only does the supply curve shift to the left but also the demand curve, leading to an even bigger decrease in the quantity of dirty energy but without resulting in large short-run price spikes that are unpopular and play into the hands of populists and climate change deniers. The whole first part of the eBook is devoted to investigating of how to curb energy demand. The chapters by Sterner and co-authors and Kotlikoff and co-authors focus on carbon taxation, while Borghesi and Ferrari as well as Cantillon emphasise social acceptability. Finally, Schubert analyses ‘sobriety’ policies and Houde studies information-based policies.

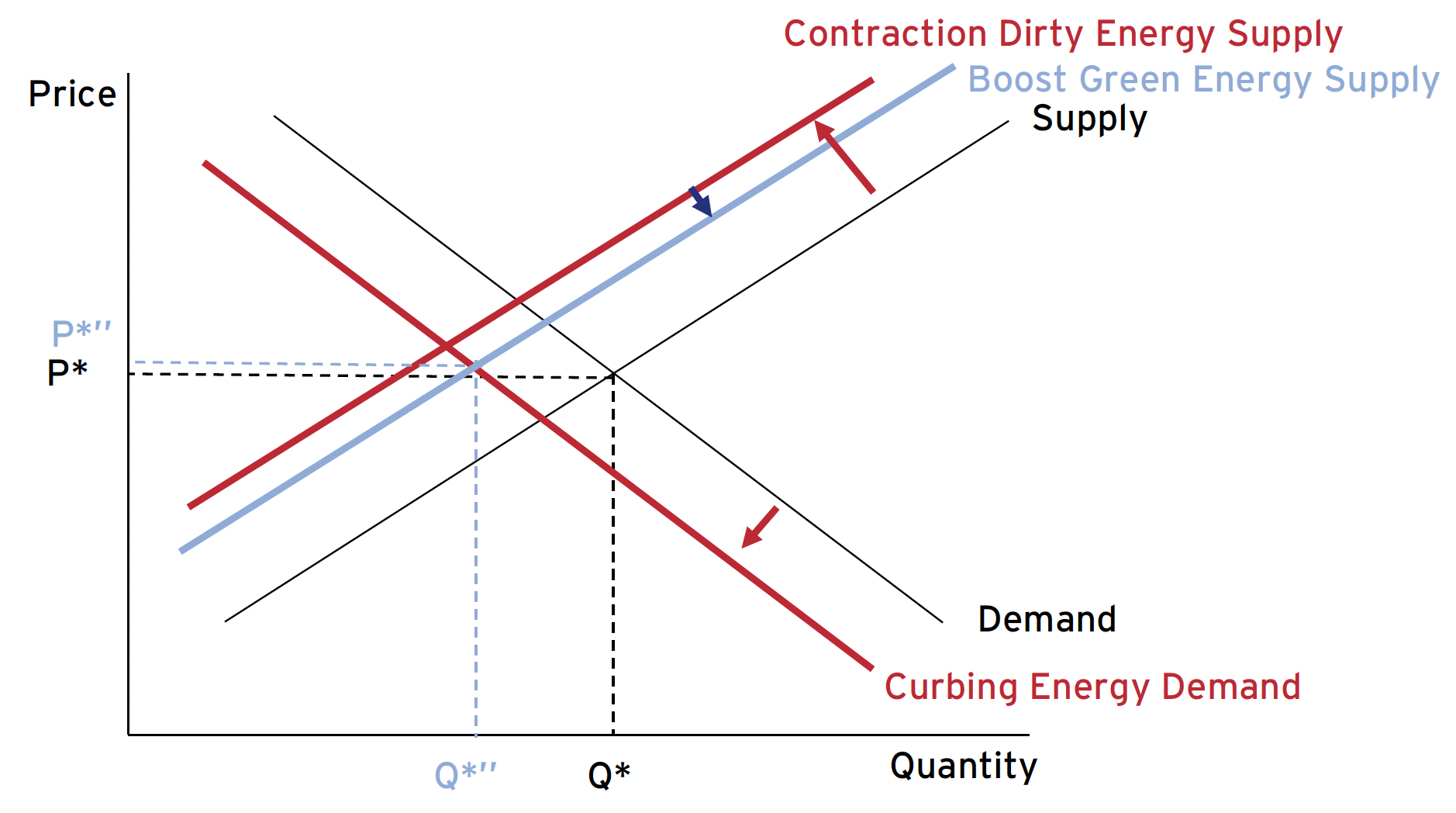

Figure 1 Price effects of the green transition

A) Supply-side climate policy

B) Contraction dirty energy supply and curbing energy demand

C) Contraction dirty energy supply, curbing energy demand and boosting green energy supply

Obviously, it goes without saying that a rapid stepping up of green energy supply will also play a key role in avoiding extreme (and unpopular) price spikes, as illustrated in Panel C. This being said, there are of course some limits to how fast one can go (for example, building new hydro power plants is a matter of several years rather than a few months), hence in the short run this stepping up of green energy supply may still be quite moderate. In the long run, however, the effect could obviously be massive, more than compensating for the drop in dirty energy. Part II of the eBook focuses on boosting green energy supply. In particular, the chapter by Pommeret treats with solar energy, while Bureau and Crampes investigate electricity markets. Last but not least, Koundouri and co-authors appraise the European Union’s (green) innovation policy.

Part III of the eBook is devoted to macroeconomic issues linked to the green energy transition, with the chapter by Girard and Bénassy-Guéré linking higher carbon prices to demand, supply and price shocks. Parry studies inequality and Mongelli provides a tour d’horizon of transition models, sustainable finance, and green investments.

De-toxifying politics

Another widely ignored aspect of our fatal fossil fuel addiction is its harmful political consequences (Ross 2012, Rohner 2023), ranging from galloping corruption and mismanagement to domestic and international warfare. By getting unhooked from oil, gas and coal, we have the potential to make the world a safer and better governed place, which is the focus of Part IV of the eBook. The chapter by Deryugina investigates the scope of the green transition to foster energy independence and security, while Laurent-Lucchetti and Trutnevyte, Arezki and van der Ploeg, and Couttenier study challenges linked to mineral mining. Finally, Rohner focuses on reducing the political risks of renewable energy production, stressing the importance of decentralised production, labour-intensiveness and local empowerment.

Time to step up our game

It is time to roll up our sleeves and convince a solid majority of people to engage in a set of far-reaching policies that are a real game changer. As a small step in this direction, the purpose of this eBook is to pinpoint the key role of these political economics issues. The stakes could hardly be higher – a successful green energy transition will yield the double-dividend of not only saving the world from looming environmental disaster, but also combatting toxic policies and reducing the risk of armed conflict around the globe.

References

Coulomb, R, F Henriet and L Reitzmann (2021), "’Bad Oil’, ’Worse’ Oil and Carbon Misallocation", Paris School of Economics Working Paper No. 2021-38.

Dechezleprêtre A, A Fabre, T Kruse, B Planterose, A Sanchez Chico and S Stantcheva (2022), “Fighting climate change: International attitudes toward climate policies”, VoxEU.org, 14 October.

Douenne, T and A Fabre (2020), “Public support for carbon taxation: Lessons from France”, VoxEU.org, 11 May.

Ewald J, T Sterner and E Sterner (2022), “Understanding the resistance to carbon taxes: Drivers and barriers among the general public and fuel-tax protesters”, Resource and Energy Economics 70: 101331.

Gallup (2021), World Risk Poll 2021: A Changed World?

Gollier, C and J Tirole (2015), “Negotiating effective institutions against climate change”, Economics of Energy and Environmental Policy 4: 5-27.

Gollier, C and D Rohner (eds) (2023), Peace Not Pollution: Going Green Can Tackle Both Climate Change and Toxic Politics, CEPR eBook.

Pigou, A C (1920), The economics of welfare, Macmillan & Co.

Rohner, D (2023), "Mediation, military and money: The promises and pitfalls of outside interventions to end armed conflicts”, Journal of Economic Literature, forthcoming.

Ross, M L (2012), "The oil curse”, in The Oil Curse, Princeton University Press (and see the VoxTalk here).