The Covid-19 pandemic and the Russian invasion of Ukraine led to very significant deteriorations of public finances in the euro area. While macroeconomic conditions and monetary policy have been normalising rapidly, fiscal policy is lagging. Many governments took advantage of the liberal interpretation of the severe economic downturn clause in the Stability and Growth Pact (SGP) to maintain unwarranted fiscal stimulus. As risks to the macroeconomic outlook remain high, rebuilding fiscal buffers when conditions allow is vital. In this column, based on the European Fiscal Board’s (EFB) assessment of the fiscal stance appropriate for 2024, we argue that fiscal policy normalisation should proceed more rapidly than currently envisaged.

In many ways, 2024 is likely to mark the return to normality in the way the fiscal rules are implemented. The severe economic downturn clause of the SGP (popularly known as the ‘general escape clause’), has been applied for three consecutive years – well beyond the criteria of a return to pre-pandemic real economic activity that was put forward by the Commission back in 2020 – but the clause will no longer apply to 2024. Thus, on 24 May 2023, the European Commission issued specific quantitative fiscal guidance to governments for their 2024 national budgetary plans, and it signalled its willingness to open excessive deficit procedures (EDPs) in 2024 based on outturn data for the preceding year.

Two crises and the extensive interpretation of the escape clause weigh on fiscal policy in 2024

The return to specific quantitative guidance based on relevant EU law is welcome to accompany the much-needed fiscal normalisation. However, its virtual absence in the three previous years created some contradictions and difficult legacies going forward. The European Commission, not challenged by the Council, used the severe economic downturn clause to effectively suspend the EU’s fiscal rules, despite stating repeatedly and rightly that this was not the case. Indeed, the clause allows for temporary deviations from the required adjustment path, provided fiscal sustainability is not endangered in the medium term.

Of course, allowing governments to respond freely to contain the economic impact of the Covid shock was appropriate and proved to be quite successful. However, the Commission continued to apply the clause to the budget plans of 2022 and 2023, despite an anticipated return to pre-pandemic real GDP in the EU and euro area.

Crucially, the Commission chose not to issue firm quantitative fiscal guidance and not to open EDPs, although it could have done so to pave the way for gradual normalisation without requiring immediate and disruptive, large-scale consolidation. The lack of quantitative guidance complicated the translation of fiscal recommendations, particularly in the 2023 budgets. Whereas the Commission discouraged Member States from pursuing a broad-based fiscal expansion and urged governments to focus on targeted energy support measures, it still lacked a clear-cut overall numerical fiscal marker.

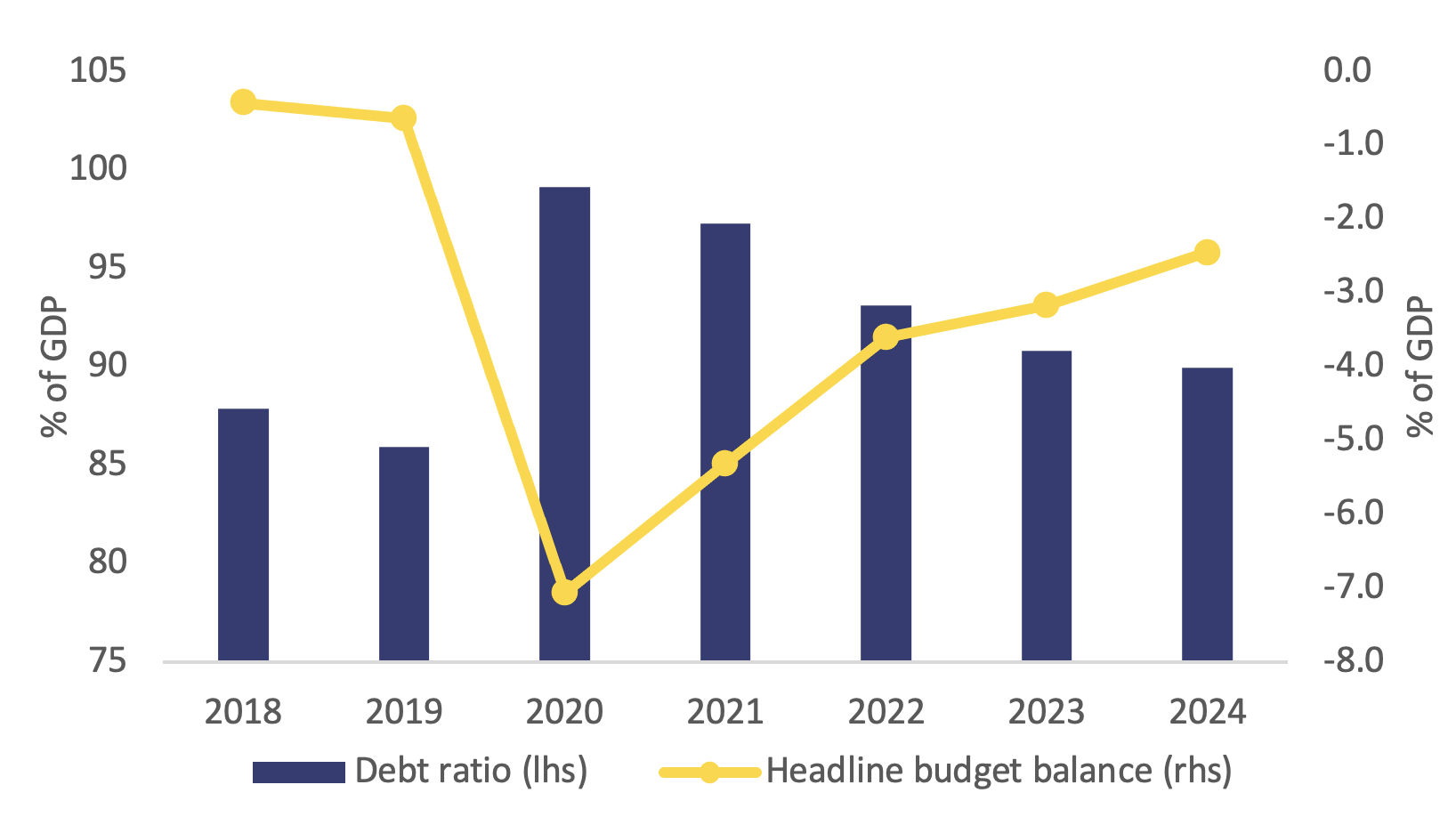

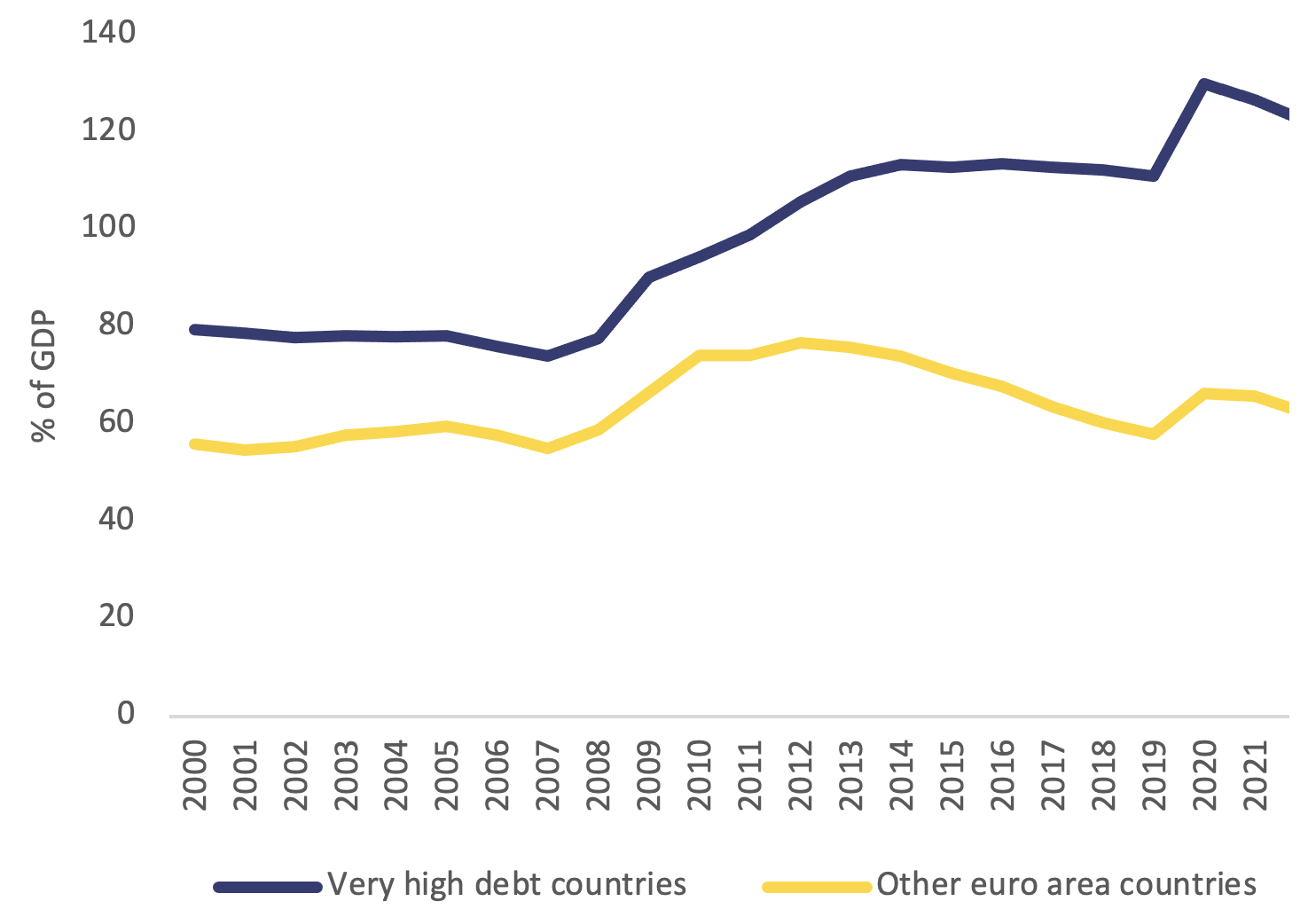

As a consequence of the two crises and essentially unconstrained fiscal policy, debt ratios have ratcheted up, especially those of countries with already high debt ratios to start with. High nominal economic growth has eased pressures on debt ratios for the time being, but sovereign borrowing costs are also on the rise, whose full effect will only be felt with some lag.

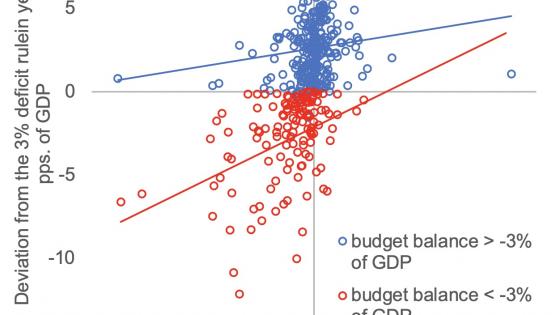

Figure 1 Impact of the crises on public finances

Source: EFB based on European Commission data.

Assessment of the euro area fiscal stance in 2024

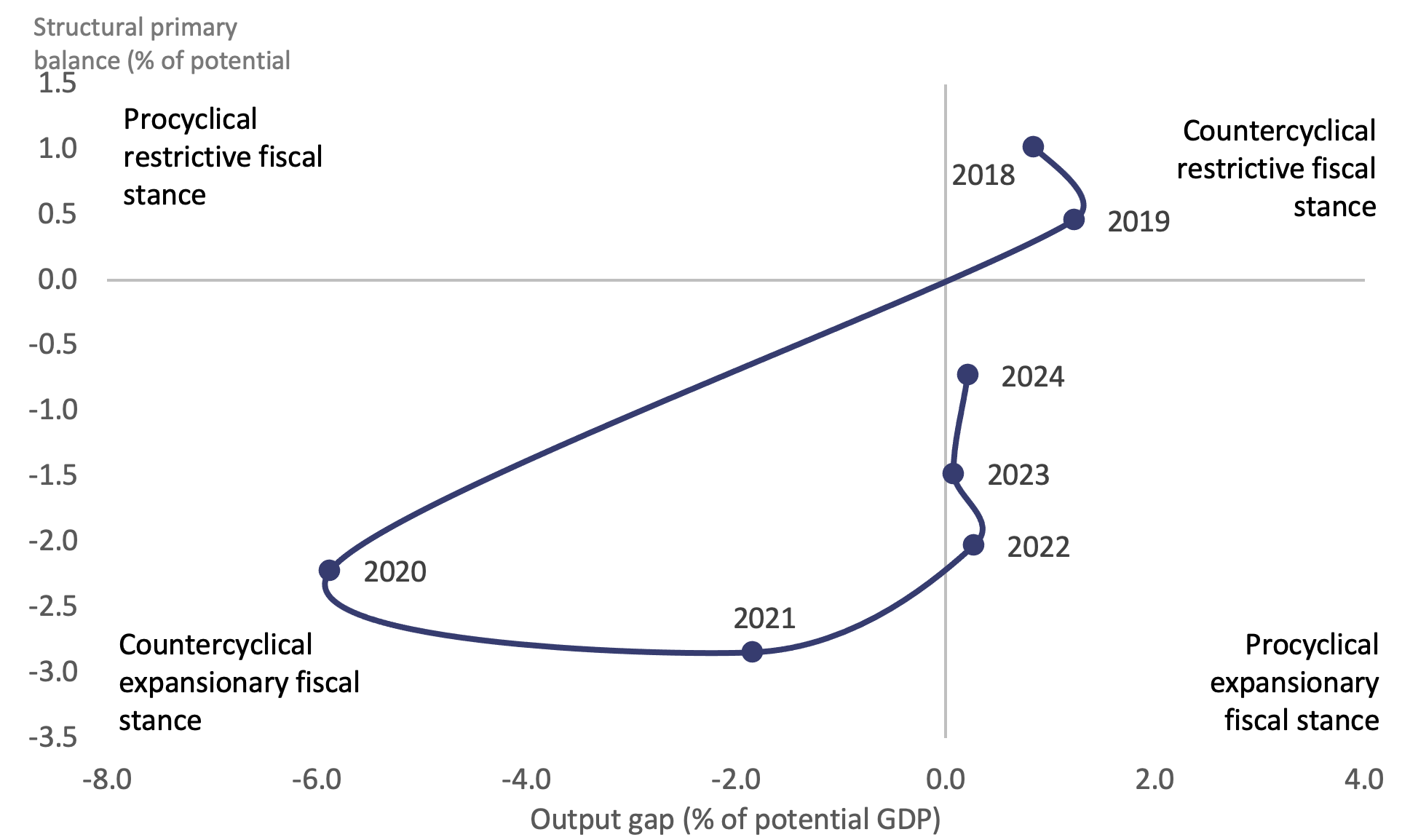

After relatively subdued but higher-than-expected economic growth in the previous year, international organisations expect solid economic growth in 2024 and an economy that operates close to its potential. The labour market continues its exceptionally strong performance, with record low unemployment and high vacancies rates. At the same time, due to the extensive interpretation of the severe economic downturn clause discussed above, the structural primary deficit in 2023 is expected to remain close to 1.5% of GDP; including interest expenditures, the deficit still sits above 3% of GDP.

Against this backdrop it would be warranted to withdraw discretionary fiscal support in the euro area. And indeed, the European Commission’s 2023 spring forecast projects a restrictive fiscal impulse of 0.8% of GDP in 2024, which would roughly halve the structural primary deficit. This projection is based on a ‘no policy change’ assumption and is driven by an expectation of a near-complete withdrawal of energy support measures taken in 2022 and 2023. The Commission’s country-specific recommendations of spring 2023 ask Member States for a structural adjustment of between 0.3% and 0.7% of GDP depending on the assessed risks to debt sustainability – unless the Member State is at, or is expected to reach, its medium-term objective. This fiscal guidance implies a required structural adjustment of 0.5% of GDP for the euro area as a whole, without considering the recommended phasing-out of energy support measures (which are estimated at around 1 ¼ % of GDP). The projected deficit reduction of 0.8% of GDP in structural terms falls short of the recommended phase out of energy measures, suggesting that some Member States are expected to use part of the roll-back of energy measures for new fiscal initiatives.

Figure 2 The euro area fiscal stance and cyclical conditions

Source: EFB based on European Commission data.

While the fiscal stance

is directionally appropriate, the structural deficit remains elevated by historical standards; it was close to balance on average over the past 20 years. Barring unexpected shocks, a swifter withdrawal of fiscal support in 2024 thus seems warranted to eventually return to this historical average in the medium term. This episode may hold lessons for any future application of the escape clause and how to guide fiscal policy also during downturns and especially the subsequent rebounds.

A relevant consideration is the well-documented tendency to underestimate the economic good times ex ante. Member States are still benefiting from comparatively low interest rate payments on sovereign debt, while a sizeable fast rising GDP deflator erodes debt-to-GDP ratios. The beneficial environment will be temporary as inflation is projected to decline, while sovereign borrowing costs continue to gradually rise as debt matures and is being refinanced at higher rates. This calls for a more cautionary approach and the building of fiscal buffers. A decisively restrictive fiscal impulse in 2023 and 2024 would also help the ECB’s efforts to bring inflation back to target, thereby reducing the likelihood of a scenario where interest rates would have to stay higher for longer.

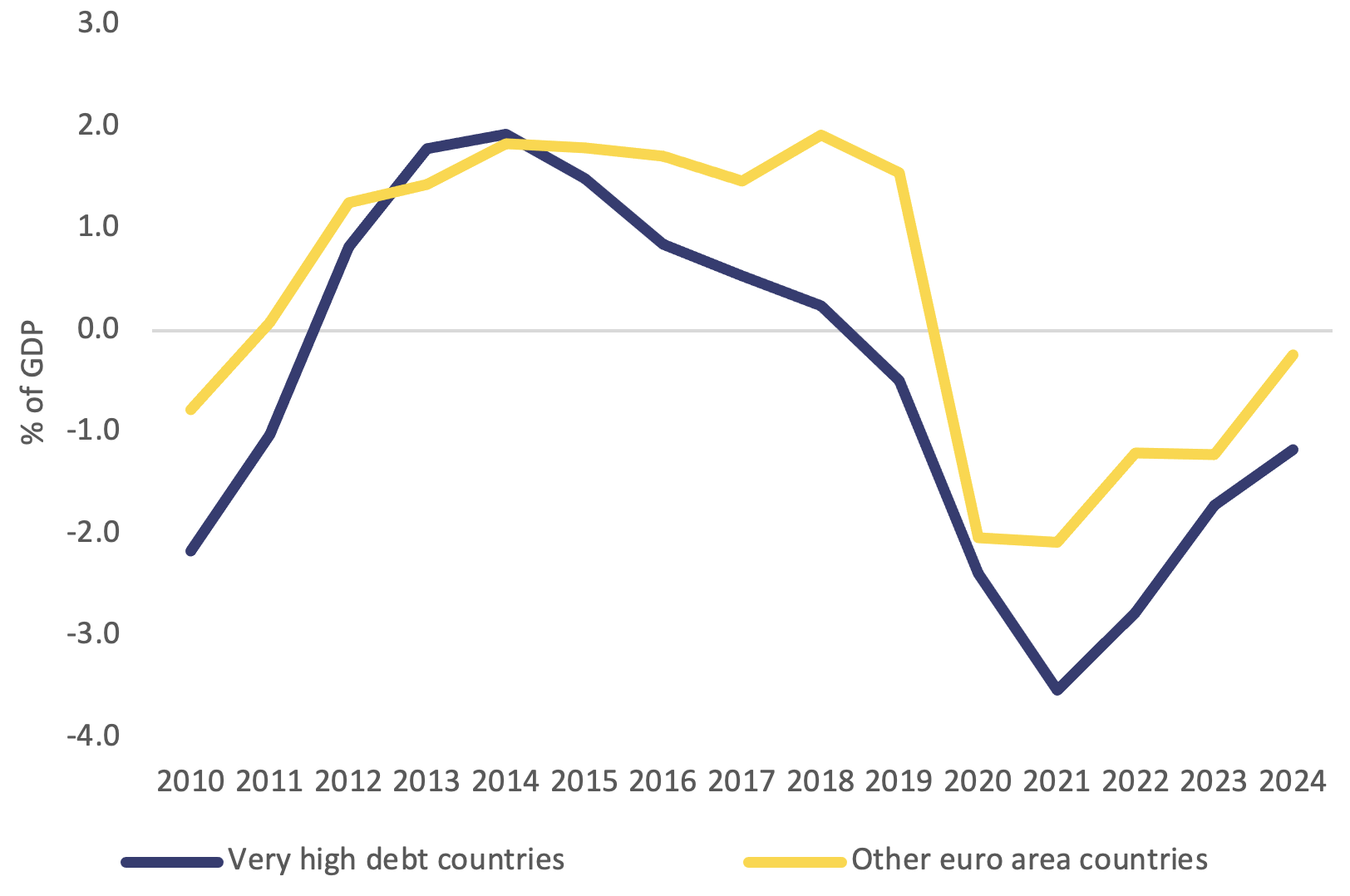

Figure 3 Debt-to-GDP ratios by country group

Figure 4 Structural primary balance by country group

Making use of benign economic conditions is particularly important for countries with very high public debt levels. These countries

are currently projected to contribute to the restrictive fiscal impulse in 2024 proportional to their share in euro area GDP. At the same time, they tend to have a structural deficit well above euro area average. They are also part of the eight countries the European Commission identified in its latest Debt Sustainability Monitor as facing high risks to sustainability of public finances in the long-term. It would therefore be prudent for very high debt countries to dial back discretionary fiscal support at a faster pace than the rest of the euro area.

Overall, euro area fiscal policy is moving in the right direction. Record-high structural deficits are gradually coming down. However, they are projected to remain too high for comfort. Given the identified risks to sustainability of public finances in several very high-debt countries and continued high uncertainty on many fronts, it would be warranted to withdraw discretionary fiscal support at a swift pace, especially measures that were meant to be temporary, and use the economic good times to build fiscal buffers. This would also help the ECB in bringing inflation back to its target, while putting Member States in a position to deal with the rising costs of aging and climate change, as well as new challenges, such as rising interest payments and costs of defence.

References

European Commission (2023), Debt Sustainability Monitor 2022.

European Commission (2023), 2023 European Semester: Spring package.

EFB – European Fiscal Board (2022), Annual Report 2022.

European Fiscal Board (2023), "Assessment of the fiscal stance appropriate for the euro area in 2024".

Larch, M, J Malzubris and M Busse (2021), “Optimism is bad for fiscal outcomes”, VoxEU.org, 4 November.