Thomas Piketty’s bestseller, Capital in the 21st century (Piketty 2014), attracted our attraction to the capital–income ratio. The capital–income ratio increases, by definition, when the rate of return on capital (assuming the return is fully reinvested) is greater than the rate of growth of the economy. This is the famous r > g inequality. If this is the future of the rich world, as Piketty argued, then capital–income ratios will continue to rise.

But will the increase in the capital–income ratio lead to an increase in interpersonal income inequality? The question is seldom asked because the answer seems obvious. If the capital-–income ratio goes up, and if the share of capital in GDP increases, then income inequality is bound to increase. Recent empirical findings of a rising capital share over recent decades in both advanced and emerging economies reinforces this view (Karabarbounis and Neiman 2013, Jacobson and Occino 2013, Elsby et al. 2013).

The three conditions for greater income inequality

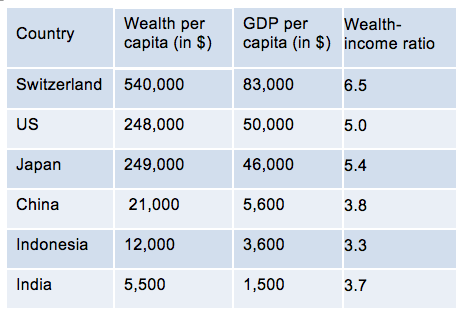

The matter, however, is more complicated. True, richer countries have higher capital-income ratios. The recent Credit Suisse (2013) report clearly supports this. Measured by current income, Switzerland is richer than in India – but the ratio of per-adult wealth to income is greater too (Table 1). So, we can expect that as countries grow richer, their capital–output ratio will increase. But, as I recently set out (Milanovic 2017), there are three conditions for this to lead to greater interpersonal inequality.

1. The rate of return must not fall to the point that it offsets the increase in the capital–income ratio.

If it did, would make the capital share in GDP constant (or even decreasing). Most recent data imply that this condition is easily satisfied.

Table 1 Wealth–income ratio in selected countries, 2011

Source: Credit Suisse (2013).

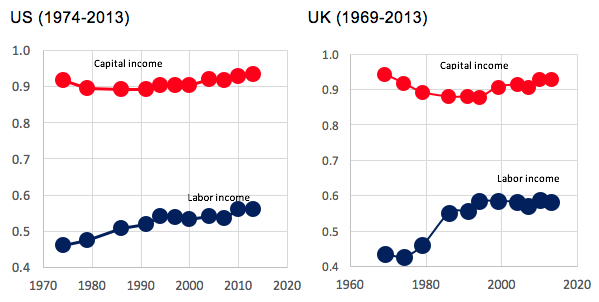

2. Income from capital must be heavily concentrated.

If concentration of income from capital were the same as concentration of income from labour, the rising share of capital would not raise overall inequality. But, of course, this is not the case. The Gini concentration of income from capital in all rich countries is astonishingly high, in the range 0.85-0.95, almost twice as high as the Gini from labour incomes. (Figure 1 shows this comparison for the US and the UK.) Clearly, as a more unequally distributed income source increases in importance, overall inequality will rise.

3. The income source that is more unequally distributed must also be positively correlated with overall income.

To see this, consider income from unemployment benefits. It is also heavily concentrated, with a Gini of about 0.9, just like income from capital. Unemployment benefits, however, are received by the income-poor, and so they push inequality down, while income from capital whereas income from capital is received by the income-rich, and so pushes inequality up. This condition is equivalent to saying that, for overall inequality to increase, the share of capital income in total income must be greater for the income-rich than for the poor. This is self-evidently true: capital income, even if underestimated in household surveys or tax data, is 15% of total income of the highest decile in the US, and is negligible among the bottom deciles (calculated from 2013 'lissified' Current Population Survey). This is true in all rich countries.

Figure 1 Gini coefficients of capital and labour income

Source: Calculated from Luxembourg Income Study data. (http://www.lisdatacenter.org/)

In the real world, all three conditions are easily satisfied. The implication is bleak: if countries want to curb the automatic spillover of greater capital share in GDP to higher interpersonal income inequality, there must be greater redistribution of current income through higher taxes. Politicians have little appetite for this.

An alternative solution: Deconcentrating capital ownership

There is an alternative solution. Go back to condition three. Now suppose that, instead of capitalism – in which the share of capital income increases almost monotonically with income level – disposable income were distributed with a Gini equal to what it is today, but that each individual had the same share of income from capital and labour regardless of where that individual was in the income distribution. The rich person’s 100 units of income would be composed of 70 from labour and 30 from capital, while the poor person’s income of 10 units would consist of seven from labour and three from capital. Note that the rich would be still as many times richer than the poor as they are today, but their share of income from capital would the same as the share of income from capital that the poor receive. Then an increase in the capital share would increase everybody’s income proportionally, and not change the overall Gini.

We can do even better. Suppose that income from labour were distributed the same as today, but that all income from capital were shared equally, on per-capita basis. Then we would move to a world in which an increase in capital share would reduce overall interpersonal inequality.

Therefore we do have an answer to how to offset the quasi-inevitable trend to higher interpersonal inequality that rich countries will face if capital share in GDP keeps on rising – as many economists assure us it will, not least because of the influence of robotics on the labour market. The answer would be a 'deconcentration' of capital ownership. It is remarkable how little – or rather, that nothing – has been achieved in this respect since Margaret Thatcher first called for “popular capitalism” in 1986. The works of Piketty et al. (2017) and Wolff (2010) for the US, Roine and Walderström (2010) for Sweden, Atkinson (2007) for the UK and others, uniformly show that the distribution of capital is now more unequal than it was 30 years ago. Inequality of income from capital has a scarcely believable Gini of 90.

Deconcentrating capital ownership can be done in at least three ways:

- By giving tax preferences to small investors so that they become more likely to own shares. One could envisage a government-funded insurance whereby shares up to a certain amount would have a guaranteed, very modest, real return (say, 1% per year) even in a case of a stock market decline.

- Workers should be encouraged through the existing mechanisms, like employee stock ownership plans, to become the owners of the companies in which they work. Obviously, when they leave they could choose to sell their shares, but the experience of having had some equity (acquired perhaps at preferential rates) may make them more willing to continue investing. In other words, the working class and small investors should enjoy the same tax and other advantages that today are granted only to the rich.

- Using capital grants funded out of inheritance taxes, as suggested by Atkinson (2015), would also broaden the ownership base.

A question of will

Two points need to be made clear. First, if the capital share in GDP keeps on rising, and if rich countries genuinely want to halt further increases in inequality, something must be done. This means either redistributing current income, or equalising asset ownership. Second, equalising asset ownership appears more promising. The tools to do this are well known. Many of them were extensively discussed in the 1970s and 1980s by Meade (1986). More recently, they were also advocated by Atkinson (2015). What we lack is the political will to do it.

References

Atkinson, A (2007), “The Distribution of Top Incomes in the United Kingdom 1908-2000” in A Atkinson and T Piketty (eds) Top Incomes over the Twentieth Century. A Contrast Between Continental European and English-Speaking Countries, Oxford University Press, Chapter 4.

Atkinson, A (2015), Inequality: What can be done? Harvard University Press.

Credit Suisse (2013), Global Wealth Report 2013, Credit Suisse Research Institute.

Elsby, M W L, B Hobijn and A Şahin (2013), “The decline of US labor share”, prepared for the Brookings panel on economic activity, September 2013.

Jacobson, M and F Occhino (2013), “Labor’s declining share of income and rising inequality”, Economic Commentary, Federal Reserve Bank of Cleveland.

Karabarbounis, L and B Neiman (2013), “The global decline of the labor share”, Quarterly Journal of Economics, (129)1, 61-103.

Meade, J (1986), Different forms of share economy, Public Policy Center.

Milanovic, B (2017), “Increasing capital income share and its effect on personal income inequality”, in Heather Boushey, Brad de Long, Marshall Steinbaum (eds), After Piketty: The agenda for economics and inequality, Harvard University Press, 235-259.

Piketty, T (2014), Capital in the 21st century, Harvard University Press.

Piketty, T, E Saez and G Zucman (2016), “Distributional National Accounts: Methods and Estimates for the United States”, NBER Working Paper 22945, December.

Roine, J and D Waldenström (2010), “Top Incomes in Sweden over the Twentieth Century” in Anthony Atkinson and Thomas Piketty (eds.) Top Incomes: A Global Perspective, Oxford University Press, Chapter 7.

Wolff, E (2010), “Recent wealth trends in the household wealth in the United States: Rising debt and the middle class squeeze: an update to 2007”, Levy Economics Institute of Bard College, Working Paper 589, October.