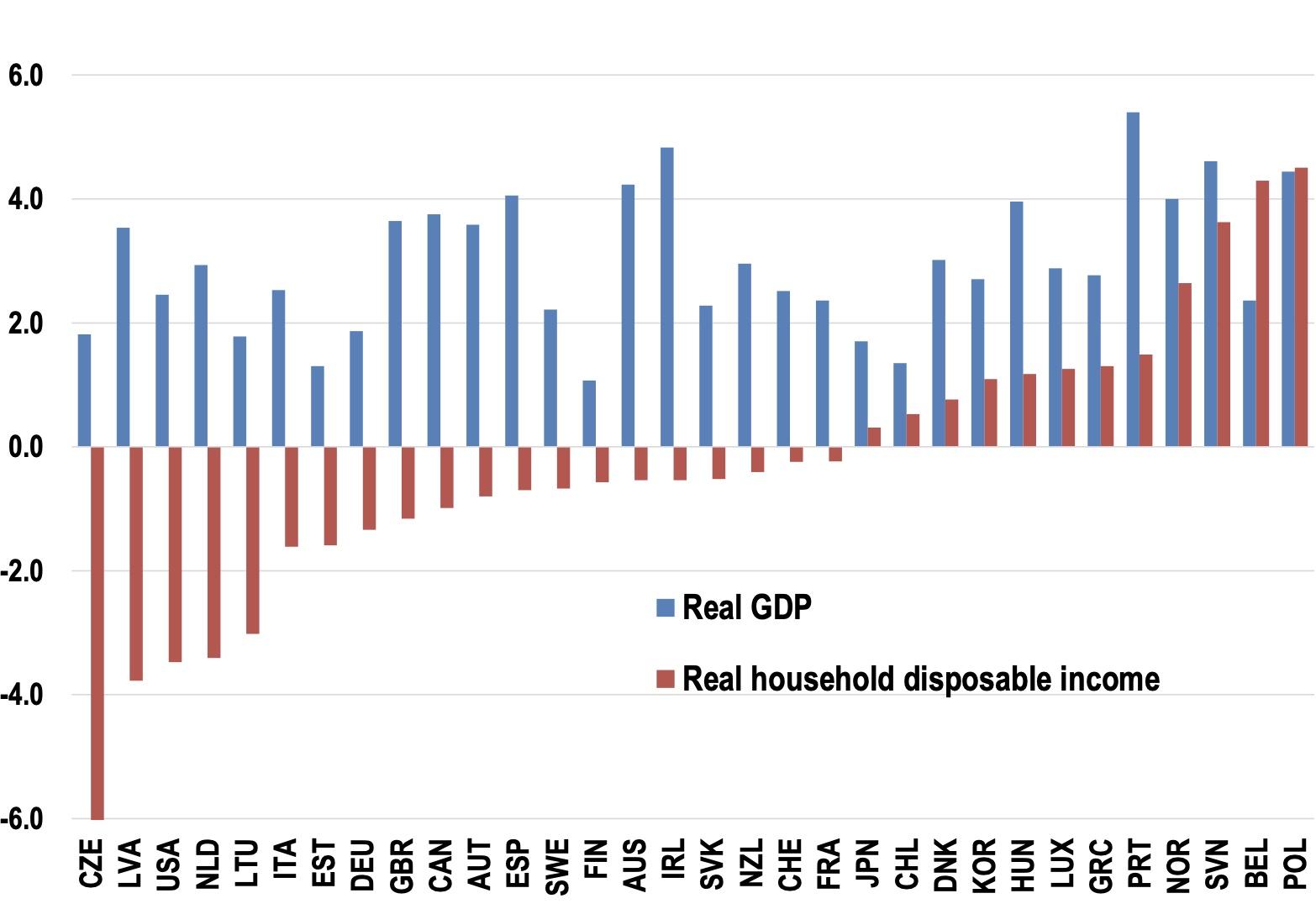

The cost of living crisis is very apparent in the latest forecasts published by the OECD (OECD 2022). The growth rate of GDP expected this year is positive for every OECD country, but the growth rate of real household disposable income is consistently lower and is negative for a majority of them (Figure 1). Moreover, the magnitude of this differential has not been experienced in some countries since at least the 1970s and is even more important given the long-standing argument that income measures based on household disposable income provide a superior measure of welfare to GDP. For example, adjusted household disposable income (AHDI)1 is used as an alternative income measure to GDP in the OECD flagship publication, How’s Life: Measuring Well-being, is a component of the OECD Better Life Index, and is more consistent with the recommendations of the Stiglitz-Sen-Fitoussi Commission on Measuring Economic Performance and Social Progress to focus on household income and consumption rather than output (Stiglitz et al. 2009).

Figure 1 Comparing projections of GDP and household disposable income

Growth per annum (%) in 2022

Note: The chart compares recent OECD projections for 2022 of growth in real GDP and real household disposable income. Only OECD countries for which national accounts data on real household disposable income is readily available are shown.

Source: OECD Economic Outlook (June 2022).

In response to the cost of living crisis, governments are rolling out temporary, timely, and well-targeted fiscal support to vulnerable households (Adam et al. 2022). Such policies might be contrasted with structural reform measures, which are typically more permanent in nature and usually take many years to raise the supply-side potential of the economy. However, our recent research considers the differential impact of a range of structural reforms on AHDI as compared to GDP (Botev et al. 2022). Our main findings can be summarised as follows:

- Increases in the real energy prices experienced by consumers and industry drive a pronounced wedge between real GDP and real AHDI: for the typical OECD country, every 10% increase in real energy prices reduces AHDI relative to GDP by about 2%.

- Some structural reform policies – including in-kind family benefits, family cash benefits, and cuts in the income tax wedge for workers with a family – have a magnified effect on AHDI, so that following a policy reform, long-run percentage changes in AHDI are larger than for GDP. All these policies work by boosting employment and raise AHDI more than GDP partly because they also raise income for households already in employment. This also means they tend to have a more rapid effect on AHDI than employment.

- Another group of structural policies, typically those where the transmission mechanism depends mainly on productivity and capital intensity, have weaker long-run effects on AHDI than GDP. Thus, while cuts in corporate taxes and policies that stimulate private business R&D still raise ADHI, the (percentage) effects are estimated to be less than half their long-run effects on GDP. Similarly, policies that promote trade openness or improve competition in product markets raise AHDI, but the percentage increase in AHDI is reduced by more than one-third relative to the gains in GDP. Other policies which may weaken the bargaining power of labour, for example a loosening of employment protection legislation, result in weaker long-run effects on AHDI than GDP, and whereas a reduction in the excess coverage of collective wage agreements is expected to have positive long-run effects on employment and GDP, it is estimated to reduce ADHI.

- For other structural policies the long-run effects on AHDI (in percentage terms) are insignificantly different to GDP, although there are sometimes important sign differences between short- and long-run effects. For example, while cutting the unemployment benefit replacement rate or minimum wage may increase employment, GDP, and ADHI in the long run, they substantially reduces ADHI in the short run.

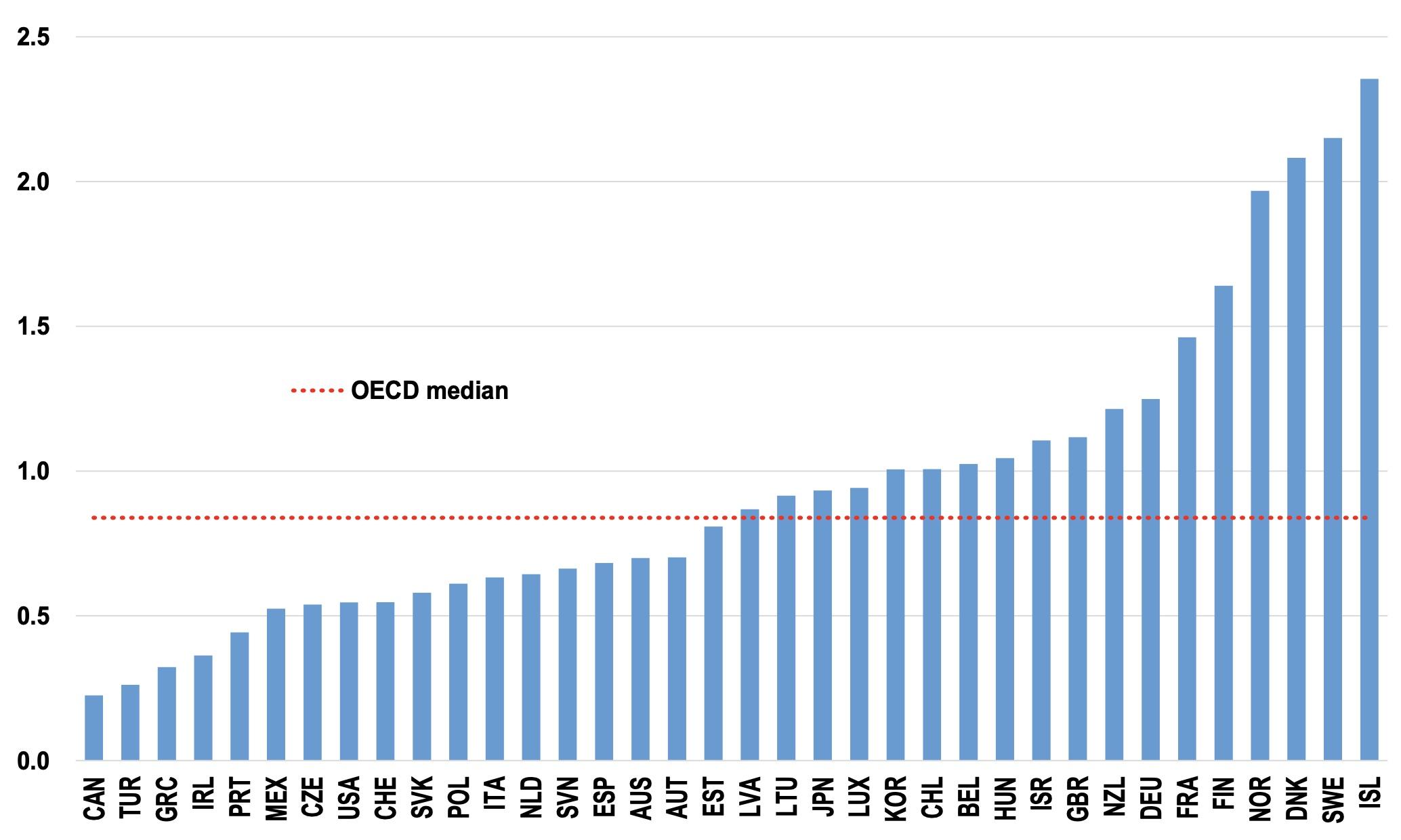

In addressing the cost of living crisis, these results provide a particularly strong case for increasing support to early childhood education and childcare, which represents over 70% of family in-kind benefit payments across OECD countries. Such policies boost long-run employment, especially for women, and have a rapid and magnified effect on household disposable incomes. Moreover, even prior to the current episode, they were identified as being among the top structural reform priorities in no fewer than 22 OECD countries, including all G7 countries (Botev et al. 2022, OECD 2021). Government spending on family in-kind benefits varies widely across OECD countries (Figure 2), with Nordic countries spending as a share of GDP more than double the OECD median. While there may be diminishing returns to additional such spending at higher initial levels, this still leaves substantial scope to increase spending in the majority of OECD countries.

Figure 2 Public spending on family in-kind benefits

Percent of GDP, 2019 or nearest year available

Source: OECD Social Expenditure Database

Finally, there are additional reasons for promoting good quality childcare, both on grounds of equity (Cornelissen et al. 2018, Felfe and Lalive 2018, Hermes et al. 2021) and because of an additional supply-side benefit via a long-run improvement in human capital and total factor productivity (Égert et al. 2022).

References

Adam, S, C Emmerson, H Karjalainen, P Johnson and R Joyce (2022), “IFS response to the government cost of living support package”, Institute for Fiscal Studies.

Botev, J, B Égert and D Turner (2022), “The effect of structural reforms: do they differ between GDP and adjusted household disposable income?”, OECD Economics Department Working Papers No. 1718.

Cornelissen, T, C Dustmann, A Raute and U Schönberg (2018), “Universal childcare: The potential to level the playing field between the rich and poor”, VoxEU.org, 7 June.

Égert, B., C de la Maisonneuve and D Turner (2022), "A new aggregate measure of human capital: Linking education policies to productivity through PISA and PIAAC scores", VoxEU.org, 28 April.

Felfe, C and R Lalive (2018), “The levelling effects of good quality early childcare”, VoxEU.org, 20 May.

Hermes, H., P. Lergetporer, F Peter and S Wiederhold (2021), “The socioeconomic gap in childcare enrolment: The role of behavioural barriers”, VoxEU.org, 7 December.

OECD (2020), How's Life? 2020: Measuring Well-being, OECD Publishing, Paris.

OECD (2021), Going for Growth, OECD Publishing, Paris.

OECD (2022), OECD Economic Outlook 2022(1), OECD Publishing, Paris.

Stiglitz, J, A Sen and J-P Fitoussi (2009), Measurement of Economic Performance and Social Progress, Report by the Commission on the Measurement of Economic Performance and Social Progress.

Endnotes

1 The adjustment in ‘adjusted’ household disposable income reflects an imputed value from public services such as education and health that provides a better basis to compare performance across countries.