A primer on (UK) inflation

David Blanchflower explains why it is most likely the jump in inflation in the UK will dissipate

Search the site

David Blanchflower explains why it is most likely the jump in inflation in the UK will dissipate

The Bank of England's Monetary Policy Committee this week sensibly pulled back from the brink at the last minute. Governor ‘U-turn’ Bailey and the new Chief Economist, Huw Pill, had tantalised markets that a rate rise was coming at the November meeting, and they believed them even though the other members of the Committee hadn’t spoken. Markets were fully expecting a rise, although in a survey taken by Bloomberg, economists were split evenly on whether a rise would come or not. The mood music rose to a fever pitch before being dashed at noon on Thursday. In the end, the rate rise didn’t come and the pound fell on a vote of 7-2, with the governor on the side of the majority voting against. My guess is that he was the last voter and, with six votes against, he wasn't going to be in a minority. After all that upset, he became ‘U-turn’ Bailey or, as The Guardian’s Larry Elliott proclaimed at the press conference, another "unreliable boyfriend” promising much and not delivering, just as Governor Carney had been labelled.

In my view, there was never any basis for a rate rise. The economy had been hit hard by the COVID pandemic and had slowed again from the spreading of the delta variant, especially among school-age children. The best analogy is that the UK was hit by an even bigger hurricane than the one Michael Fish failed to spot. It takes a while to restore electricity and rebuild. We still don’t know how long rebuilding will take, especially as the payments to the furloughed workers have just been removed, there have been cuts to Universal Credit, and National Insurance payments for employers and employees are set to rise. Consumer confidence and output have ticked down again.

My concern also is that there are signs the US may be headed for recession based on declines in consumer confidence, which have predicted six of the last six recessions in the US since 1980. The GfK consumer confidence index in the UK has also been declining the last three months. Recall that when the US coughs, the UK catches a cold. The right course of action right now is to wait and see. We should note, of course, that every rate rise – or call for one – in the last dozen years has, in my view, been in error. The main reason is that the rise in inflation is clearly transitory and will fall away back to around 2% by year end. Nothing for the Monetary Policy Committee to do here.

The day before, the Federal Reserve started to reduce how much stimulus it was putting into the US economy, by buying fewer assets every month – they are reducing the amount of stimulus into the US economy by $20 billion a month, but still putting in $120 billion a month. Chair Jerome Powell made it clear at his press conference on Wednesday that rates were not going to rise any time soon as inflation is transitory, just as it is globally. Christine Lagarde, President of the ECB, had said much the same over the last month. Governor Bailey admitted as much at his press conference the following day.

Why is the rise in inflation likely temporary? Let me explain. Inflation is the change in prices of a representative basket of goods. If the prices of most goods rise, people can stop buying them altogether and go for a cheaper substitute. What is in that basket of goods changes over time as people move away from buying dearer goods and replace them with cheaper ones. Some goods people can’t substitute, like milk, but other goods fall in price. Timber prices rose sharply and fell back as people stopped buying wood. In September the price of bread and cereals fell 0.9% on the month, so buy bread.

First off, we need to clarify that central banks target price changes, not price levels. If in year one prices rise from $100 to $103, in year one inflation is 3%. If in years two and three prices remain at $103, prices are clearly higher than they were in year one, but in both year two and year three inflation is zero. In addition, people have trouble with this question: “If inflation goes from 3% in year one to 2% in year two, have prices gone up, down or stayed the same?” The answer is they have risen, but at a slower rate. People struggle when asked what the inflation rate is, and usually overestimate it.

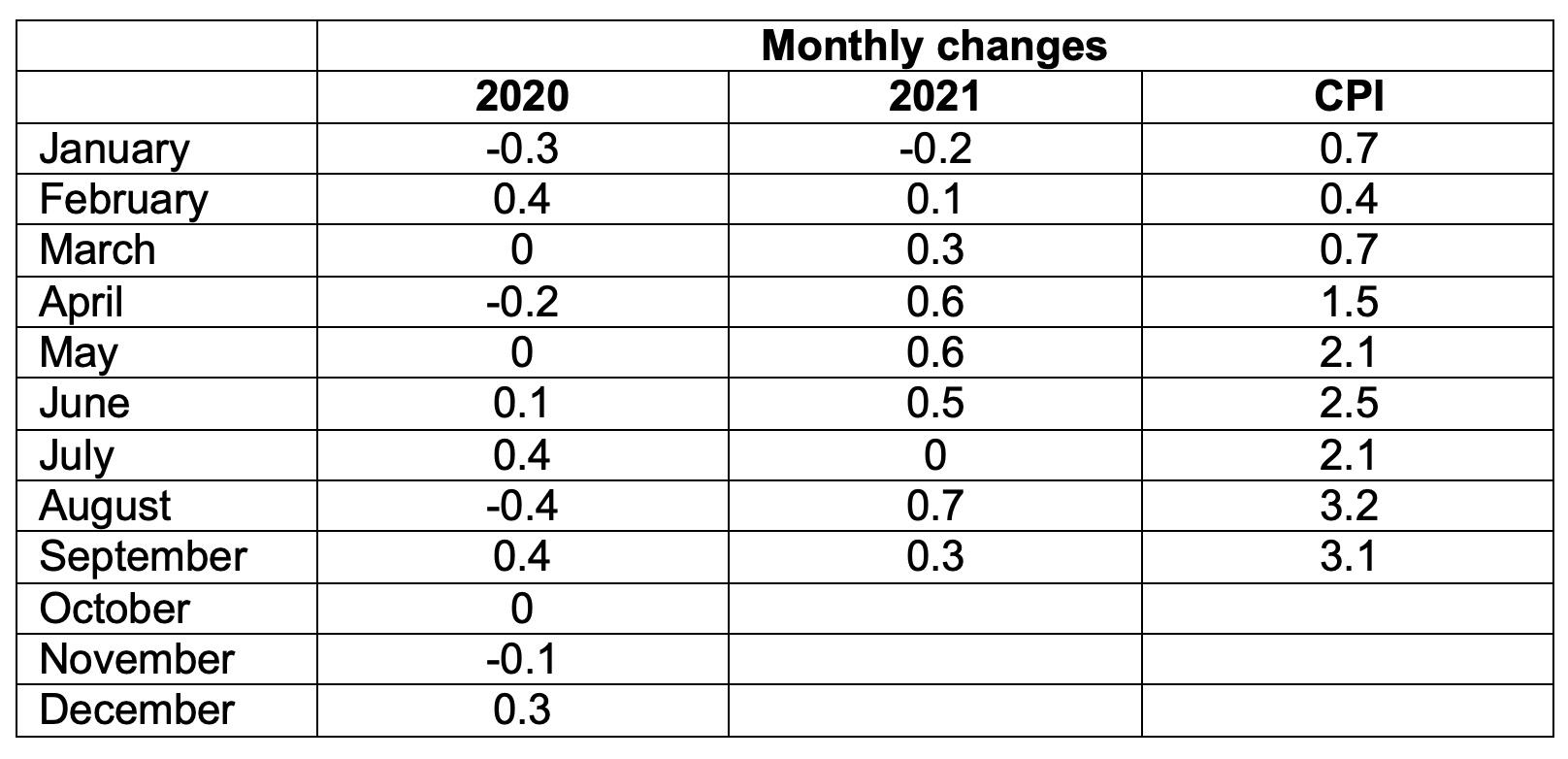

How CPI inflation changes each month is actually highly predictable. Let me explain. As a first approximation, it is in fact simply the sum of twelve successive monthly changes. Each month the ONS reports the CPI for the month as well as monthly changes for this month. Let me take an example. The ONS declared that the CPI for December 2020 was 0.6%. It turns out that is simply the sum of the 12-monthly changes from January to December 2020. Next month, January 2021, 11 of the changes to be used in the calculation are already known – i.e. February through December. We are going to get a new number for January 2021 that replaces the -0.3 for January 2020. So ,dropping the -0.3 and acquiring the -0.2, the CPI rises from 0.6% to 0.7%. In the next month we have the 0.7% and we dropped a 0.4% and gained a 0.1%, so the CPI was 0.4%, and so on. These one-off big numbers will drop out next year and be replaced with smaller ones, so inflation falls. It is hard to imagine these jumps repeating themselves next year, which is what would be required for this inflation to not be temporary.

Over the next couple of months, inflation is set to rise as the 0 and -0.1 drop out and are likely replaced with bigger numbers. An issue arises because inflation can rise either because a low number is dropped or a high number is acquired. Acquiring higher numbers is worse. What we are going to see over the next few months is tat the big numbers will drop out and likely will be replaced with smaller ones, so inflation will fall.

There is little chance that the price increases this year will be repeated next year. These are uniquely uncertain times and the right thing for monetary policy is to wait and watch and see what develops. Hopefully, COVID will disappear into the ether and things will be back to normal; the last thing the UK needs is for the Monetary Policy Committee to make an error and raise rates too soon and make the transition to normality harder.