The urgent need to decarbonise the world economy raises questions about whether the countries’ workforces possess the skills needed to support the widespread diffusion of climate-friendly technologies (‘green’ skills) (Vona et al. 2015, 2018). Since it can take a long time before the effects of reforming education systems can be seen, continuing progress towards climate goals will depend on improving the allocation of the existing stock of human talent (Adalet McGowan and Andrews 2017).

If the skills profile of jobs in the expanding green sector (Figure 1) has little overlap with the skill profile of contracting brown and automatable sectors, then the barriers to reallocation and adjustment costs will be higher. Moreover, worker displacement in polluting sectors without smooth reallocation towards good green jobs can also reduce the political acceptability of climate policies (Vona 2019 and Bircan et al. 2023), slowing down decarbonisation efforts. As a result, policymakers might need to consider diverting funds from subsidising green physical capital to green human capital.

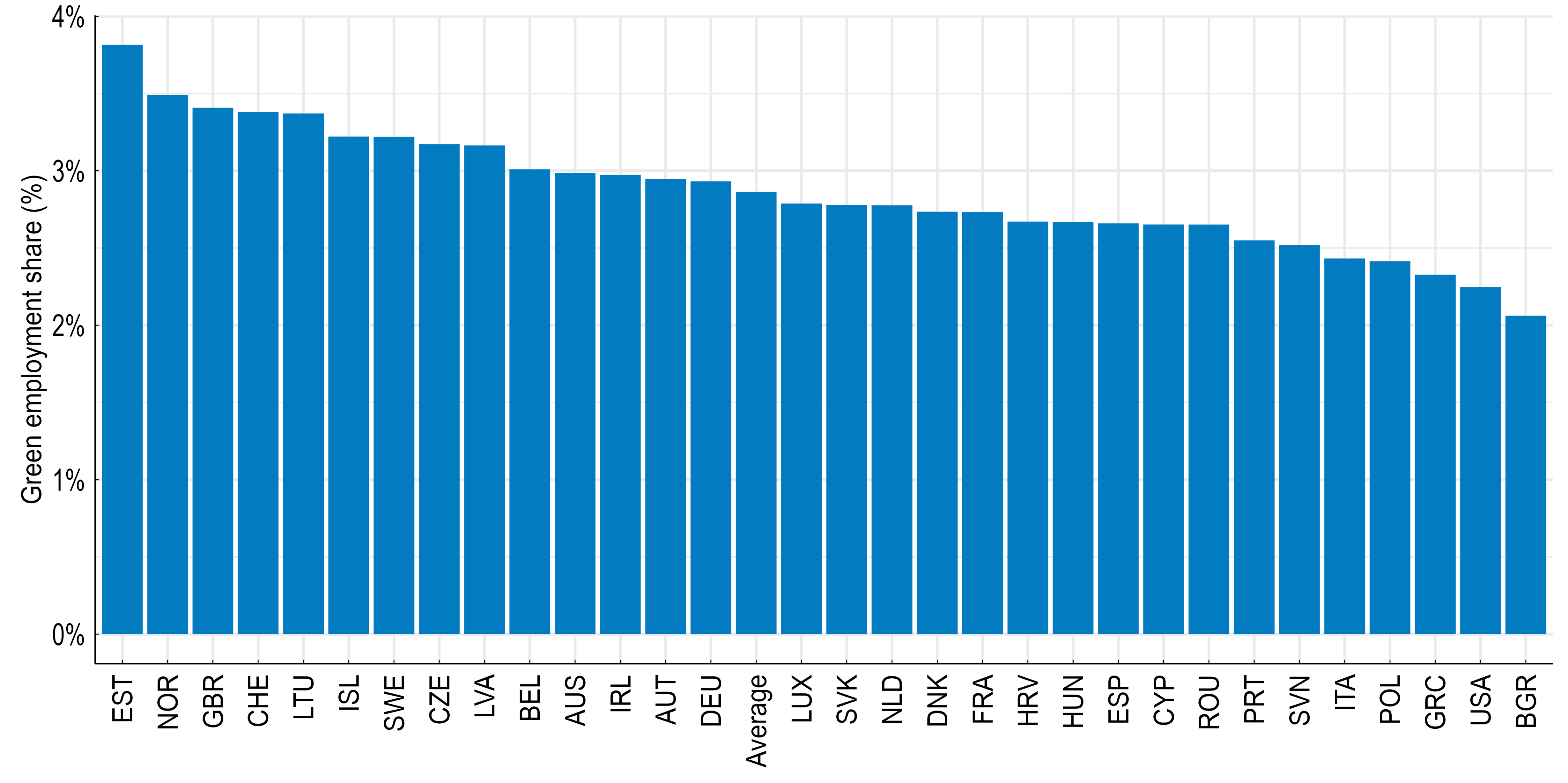

Figure 1 Green employment share (share of tasks performed in the economy that are related to decarbonisation)

Notes: The green employment share corresponds to the number of people employed in each occupation, weighted by their ‘greenness’ as a percentage of total employment. The greenness of occupation is measured as the proportion of tasks that contribute to the decarbonisation of the economy. This is equivalent to the share of tasks performed in the economy that are related to decarbonisation.

In Tyros et al. (2023), we explore the skills supply of countries’ workforces and the skills similarity between green, brown, and highly automatable occupations. We find significant cross-country variation in the supply of green skills, indicating that some countries are in a better position to create green jobs.

Next, starting from Vona et al. (2018), we confirm that workers in brown jobs have, on average, the right skills to transition to green jobs. The main exception is workers in brown production occupations, who make up a sizeable share of brown employment. We find that workers in occupations with a high chance of being automated in the near future do not, for the most part, have the required skills for such a transition, indicating that those ‘left behind’ by automation may not easily find work in the expanding green sector.

Below, we elaborate on the four key points of our work, based on the O*NET and national employment share datasets.

Green jobs and green skills

We use US data to identify green, brown, and highly automatable occupations (Table 1). Green occupations are those that have 10% or more of their tasks being related to the decarbonisation of our economy (i.e. for an average of 20 tasks per occupation, those that have at least 2 green tasks). Brown occupations are those that are extensively hired by highly polluting industries, while highly automatable occupations are those that are expected to have a large share of their tasks automated in the near future.

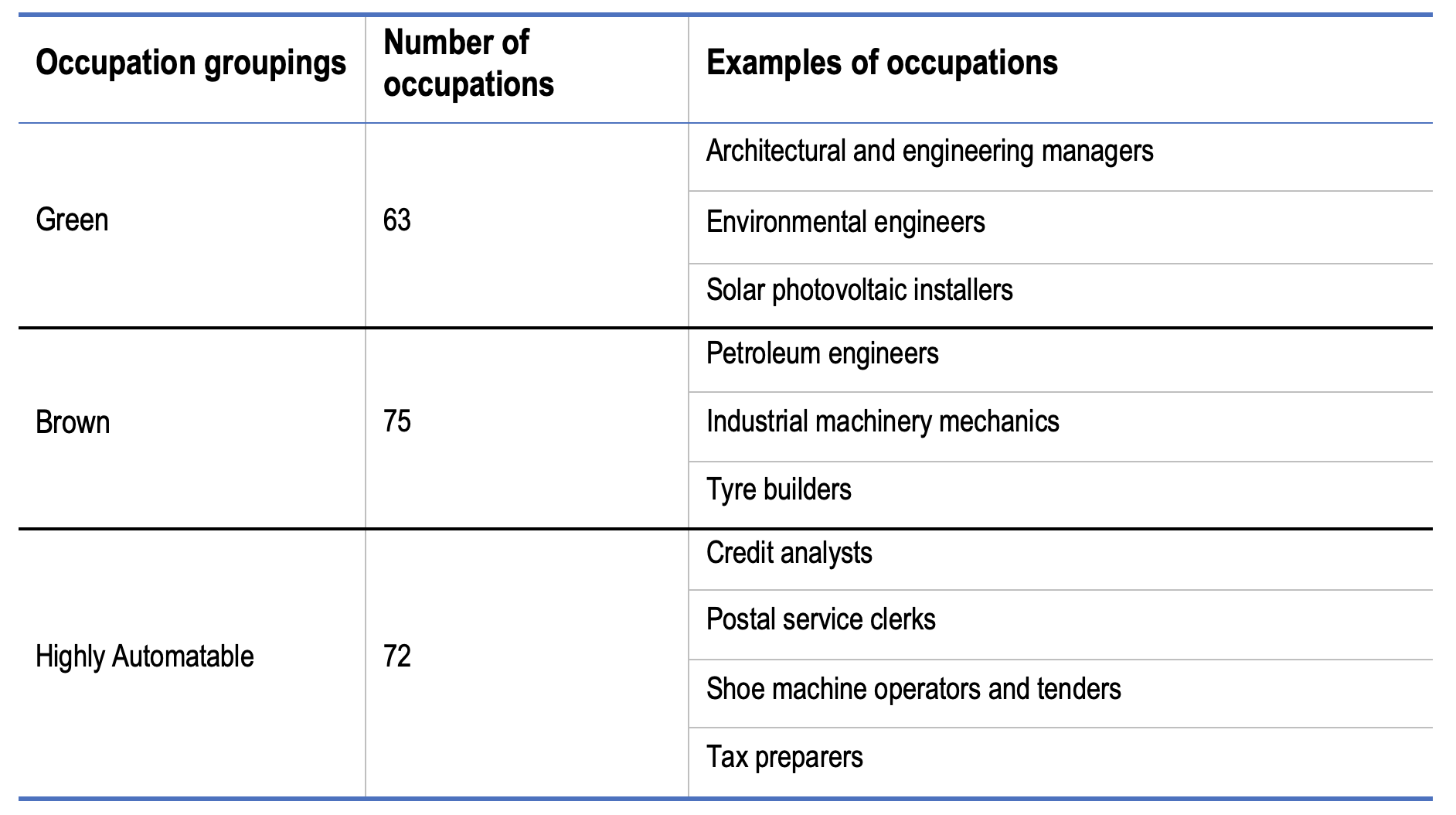

Table 1 Green, brown, and highly automatable occupations

Notes: We follow Vona et al. (2018) to identify green and brown occupations and Frey and Osborne (2017) to identify highly automable jobs. Green occupations are defined as those with at least 10% of their tasks being green, brown occupations as those with a relatively high employment share in polluting industries, and highly automatable occupations as those with at least a 95% chance of being automated in the future.

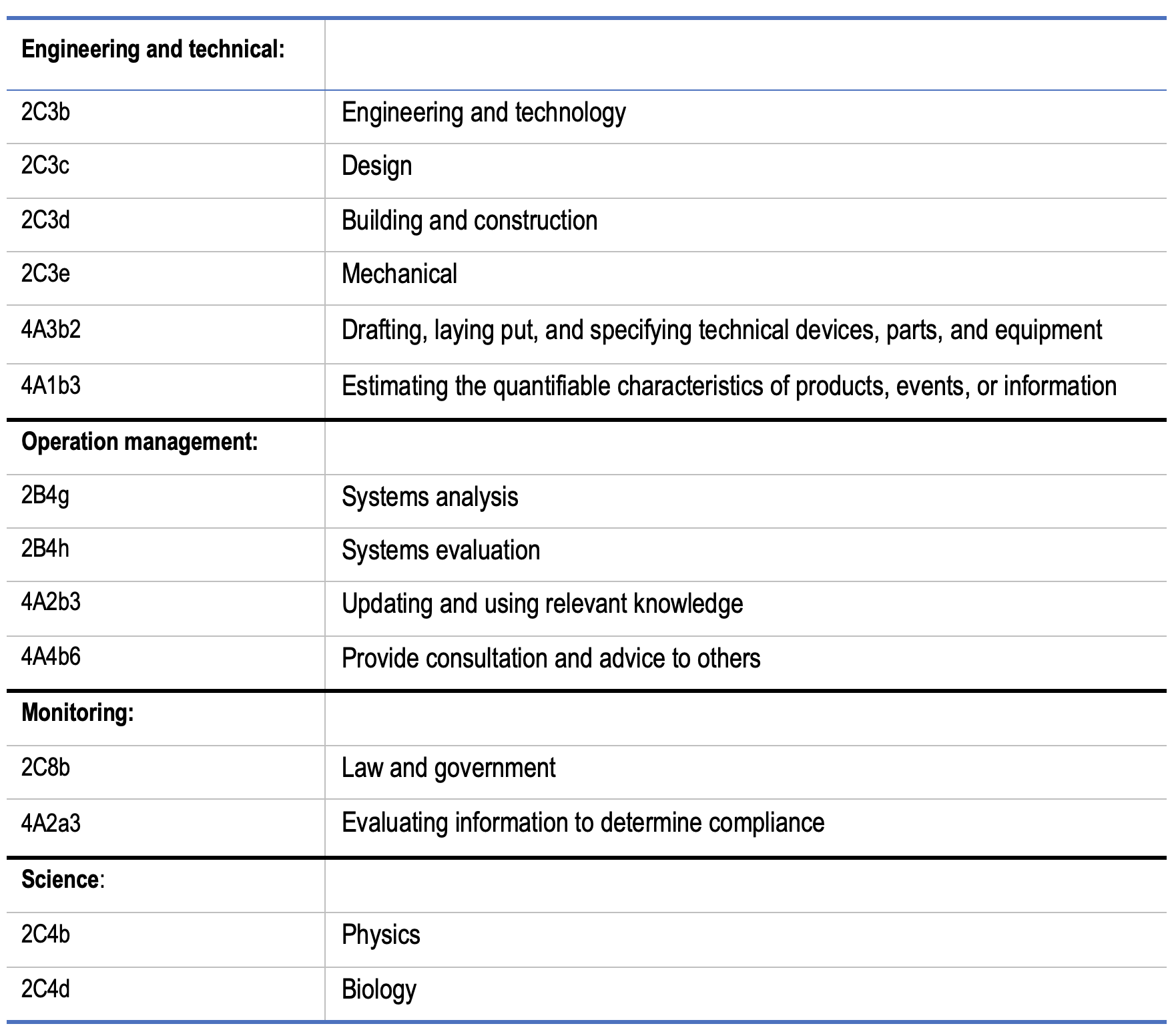

One important determinant of the ease with which jobs can be reallocated across firms and industries under the green and digital transitions is the extent to which the skills needed to perform green tasks are commonly found in brown or highly automatable occupations. Vona et al. (2018) identify four sets of skills that are typically required to perform green tasks (Table 2): engineering and technical, operation management, monitoring, and science skills. The first set of skills is needed to use new, green technologies, the second for managing new, green projects, and the third for compliance with relevant regulations. The last encompasses the necessary basic science skills to create new technologies.

Table 2 Skill sets required to perform green tasks

Notes: Vona et al. (2018) identify 14 O*NET skills that are significantly more often required by green occupations compared to other occupations and name them green skills.

Countries have significantly different supply of green skills

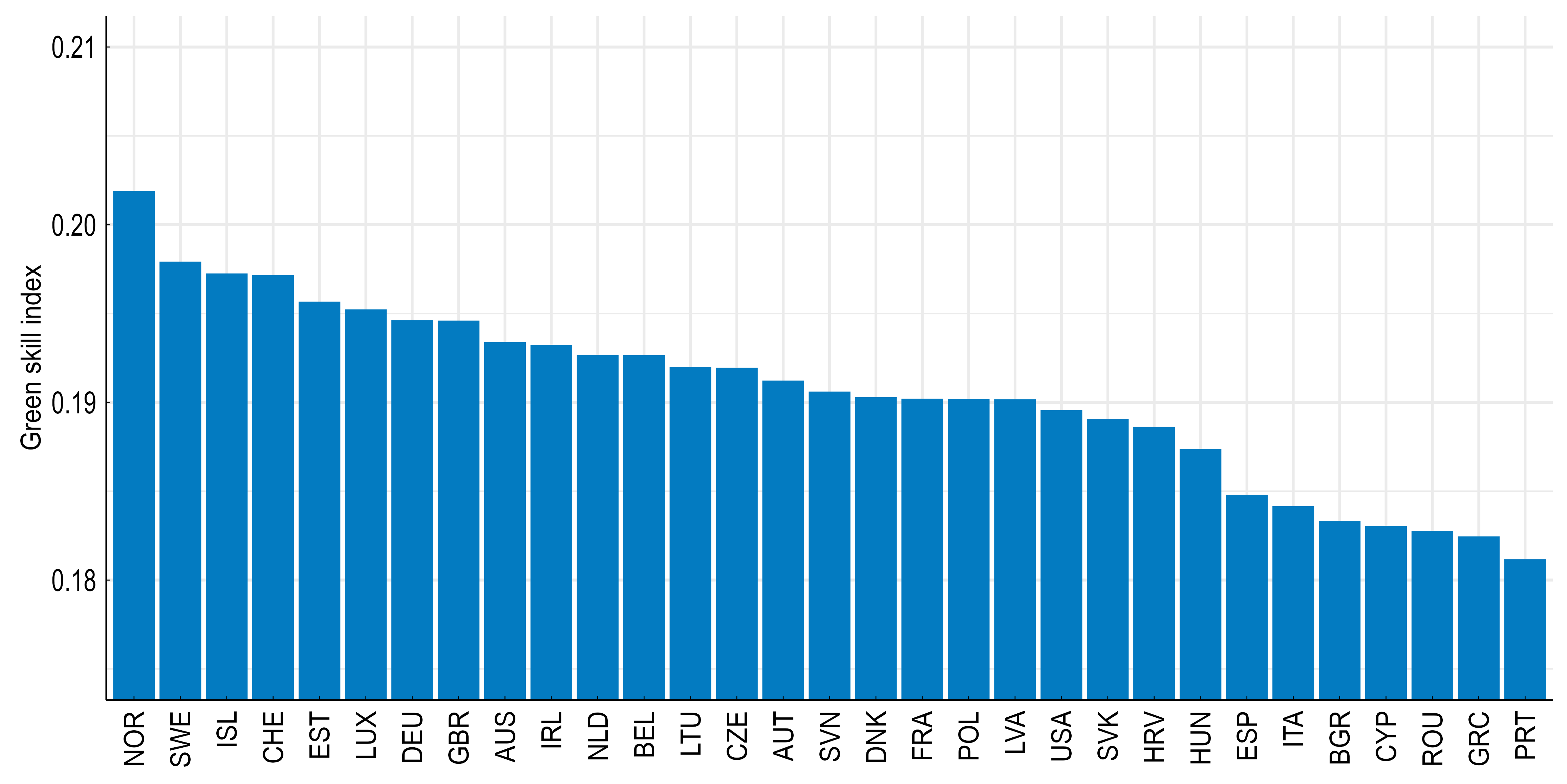

We first examine how broadly these skills are observed in individual economies. We create the Green Skill Index that measures the supply of these skills in the economy and apply it to employment shares of various OECD and non-OECD EU countries. We find a large variation across countries, with the underlying green-skill level of the workforce being much higher in Northern European countries than in Southern and Eastern Europe (Figure 2). This variation is of similar size to the one observed by Popp et al. (2020) across US Metropolitan Statistical Areas, which they find played an important role in the creation of green jobs as a result of green stimulus measures. Therefore, the differences in the green-skill supply that we observe across countries are expected to have a quantitatively significant effect on the ease with which they will create green jobs.

Figure 2 The Green Skills Index for our sample countries

Workers in brown jobs (except production jobs) have the skills to transition smoothly to green jobs

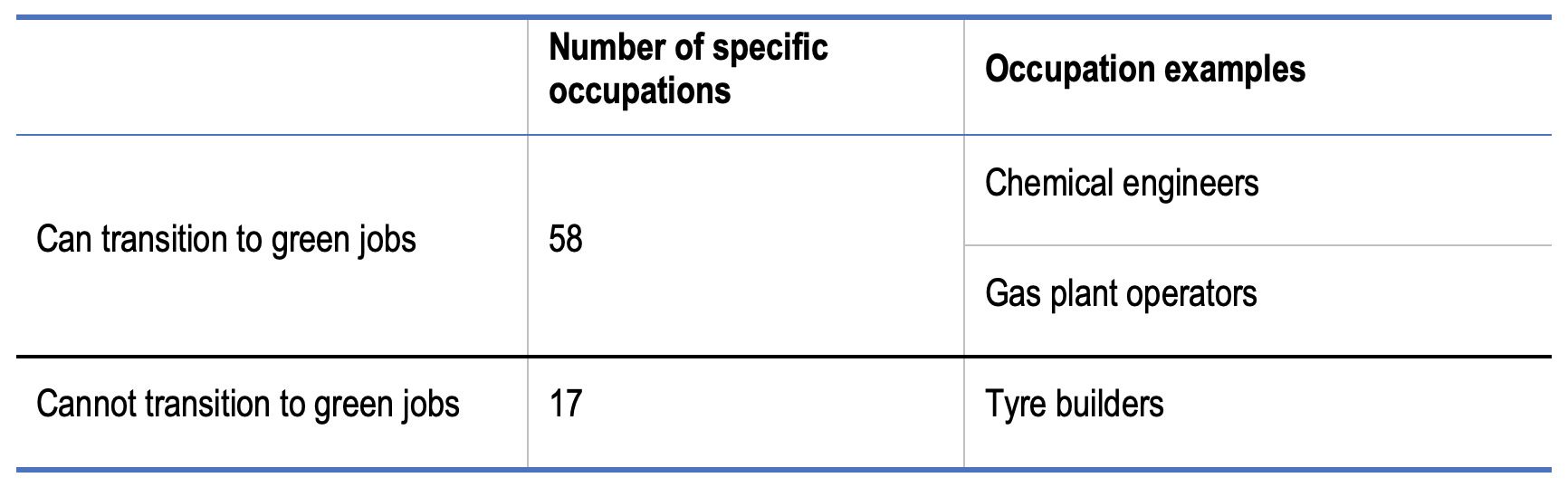

Using the O*NET skills data, we estimate the productivity of a brown-occupation worker after transitioning to a green occupation. We find that most workers in brown occupations do have the skills that would allow them to transition to a green job as their sector contracts (Table 3).

Table 3 Brown-occupation workers and ease of transition to green jobs

Notes: The number of brown occupations with skill requirements close enough to at least two green occupations that would make it feasible for a worker to transition with minimal retraining. Some examples of brown occupations are presented.

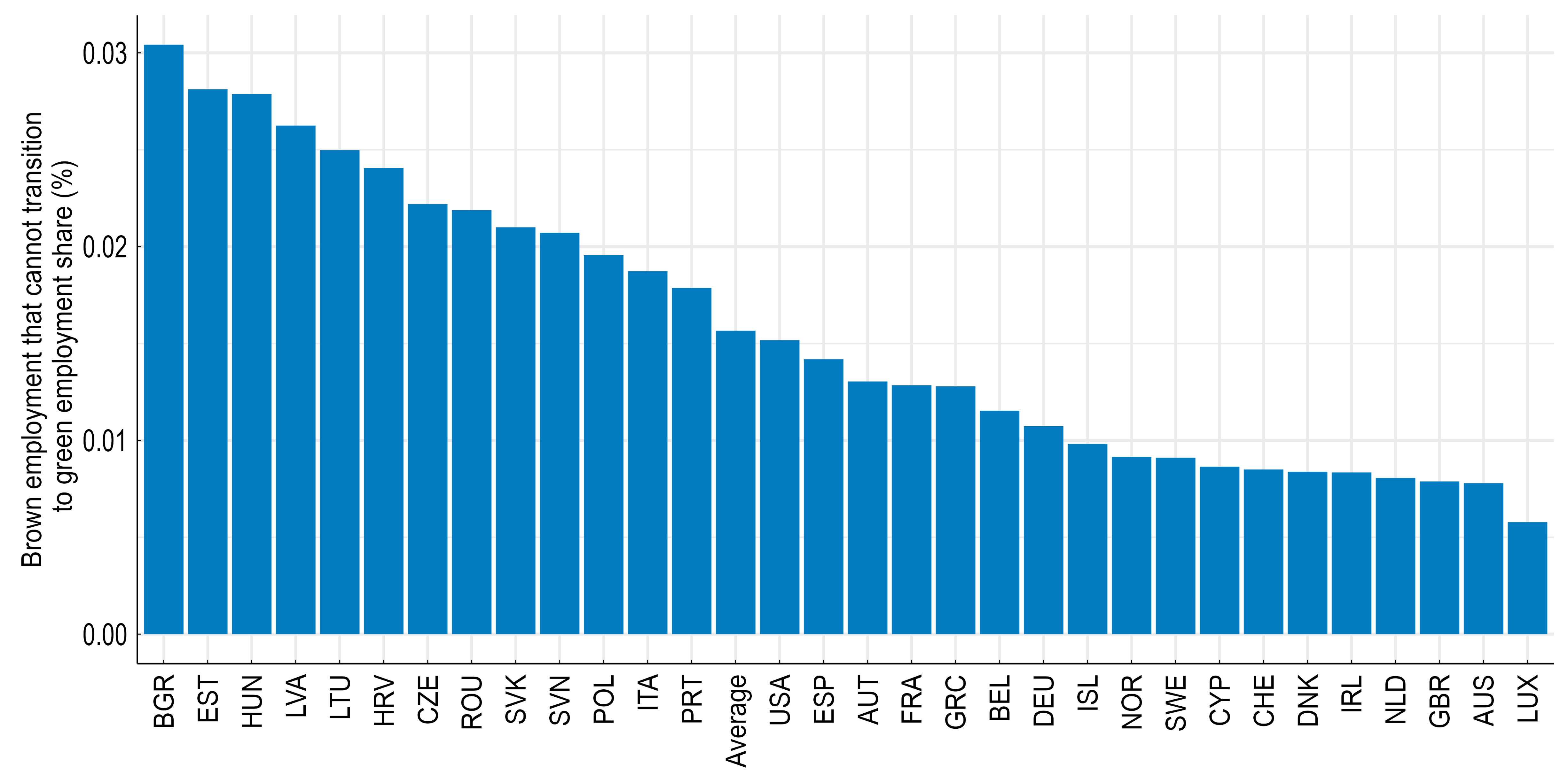

Most of the brown-occupation workers who do not have the necessary skills to transition are concentrated in production occupations, suggesting that policy efforts may be needed in this area to effectively manage transition costs. We calculate the employment share of those brown-occupation workers who cannot transition to green jobs and find it to be sizeable for a number of countries (Figure 3).

Figure 3 The employment share of brown occupations whose workers cannot easily transition to green occupations

There is limited scope for the green transition to reinstate workers from highly automatable occupations

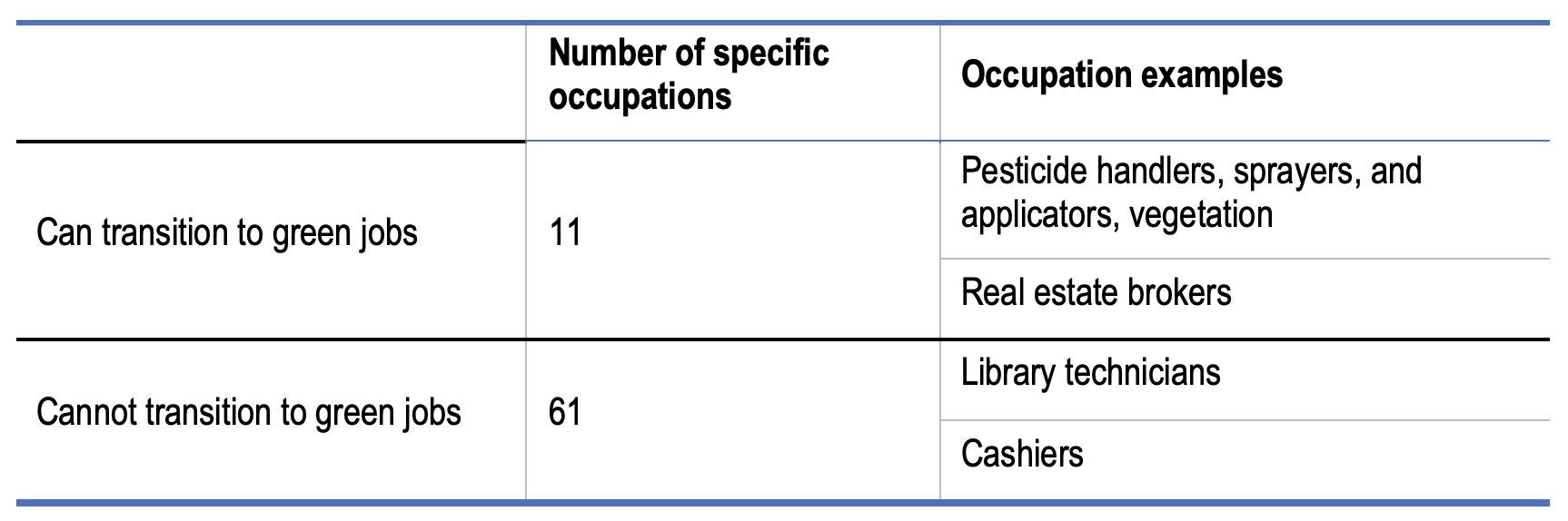

Similarly to the brown sector, we study the possible transitions to green occupations of workers in highly automatable occupations (Table 4). Unlike our results for the brown sector, highly automatable occupation workers do not, in general, have the right skills to transition. This indicates that the new types of jobs created by the green transition will not necessarily provide opportunities to directly reinstate workers displaced by automation.

Table 4 Workers in highly automatable occupations and ease of transition to green jobs

Notes: The number of highly automatable occupations with skill requirements close enough to at least two green occupations that would make it feasible for a worker to transition with minimal retraining. Some examples of highly automatable occupations are presented.

Policy and the political economy of the green transition

Although the cost of creating and purchasing new, green technologies is the largest barrier to decarbonising our economies, the effect of the labour market is also of first-order importance (Den Nijs and Tyros 2023). Green skills shortage and imperfect sorting increase the cost of adopting new, green technologies, slowing down the green transition.

A key question is whether policy frameworks can foster the accumulation of green skills over time (e.g. education policy) and effectively reallocate the existing stock of skilled workers to supply the green transition. This brings into closer focus the need for:

- green up-skilling for the workforce as a whole

- retraining to equip workers in the ‘high-potential’ occupation groups with the skills to transition to green jobs (these skills can be different from green skills (Chen et al. 2020)

- reducing policy barriers to efficient resource reallocation

Our results reveal a robust cross-country correlation between greater environmental policy stringency and higher green-skill supply as well as between stringent employment-protection legislation and a higher employment share for brown workers who cannot transition to green jobs. This suggests that environmental policy creates demand for green skills by incentivising investment in low-carbon technologies, while employment protection can create barriers to the exit of low-productivity polluting firms. These are an important reminder of how environmental policies and broader structural reforms can interact to direct human talent in a direction that is conducive to the green transition.

These policy considerations complement earlier findings indicating that brown and green industries are often concentrated in different regions of the country, which underscores the need for retraining and for industrial policies that take into account both spatial and skills mismatches (Vona 2019, Aklin 2023).

References

Adalet McGowan, M, and D Andrews (2017), “Labour market mismatch and labour productivity: Evidence from PIAAC data”, Research in Labor Economics 45: 199–241.

Aklin, M (2023), “Green jobs for fossil fuel workers: The implications of geography and skills for the clean energy transition”, VoxEU.org, 23 December.

Bircan, C, L Kitzmüller, S Noor, and N Satish (2023), “Labour markets in the green economy”, VoxEU.org, 22 November.

Chen, Z, G Marin, D Popp, and F Vona (2020), “Green stimulus in a post-pandemic recovery: The role of skills for a resilient recovery”, VoxEU.org.

Den Nijs, S, and S Tyros (2023), "Green technology adoption and skill reallocation", Tinbergen Institute.

Frey, C, and M Osborne (2017), “The future of employment: How susceptible are jobs to computerisation?”, Technological Forecasting and Social Change 114(2017): 254–80.

Tyros, S, D Andrews, and A de Serres (2023), “Doing green things: Skills, reallocation, and the green transition”, OECD Economics Department Working Papers 1763.

Popp, D, F Vona, G Marin, and Z Chen (2020), “The employment impact of green fiscal push: Evidence from the American Recovery Act”, NBER Working Paper w27321.

Vona, F, G Marin, D Consoli, and D Popp (2015), “Green skills”, VoxEU.org, 22 May.

Vona, F, G Marin, D Consoli, and D Popp (2018), “Environmental regulation and green skills: An empirical exploration”, Journal of the Association of Environmental and Resource Economists 5(4): 713–53.

Vona, F (2019), “Job losses and political acceptability of climate policies: Why the ‘job-killing’ argument is so persistent and how to overturn it”, Climate Policy 19(4): 524–32.