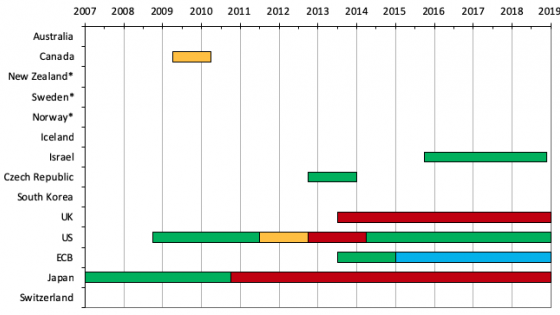

Since a year after the onset of the Covid-19 pandemic, there has been a global resurgence in inflation (Jordá and Nechio 2023). This became more pronounced in the months following the Russian invasion of Ukraine (Seiler 2022). These events represent supply shocks, which not only increase inflation but also negatively impact output (Baldwin 2020, Alessandri and Gazzani 2023). Concerns over a possible looming recession have also risen (Liang 2022, O’Donnell 2022). This has led to disagreement amongst economists on how monetary policy makers should best react. Some advocate setting high interest rates to tame inflation (Giles 2023), while others are more concerned with exacerbating recession risks (World Bank 2022). Forecasting the path of interest rates became a more difficult task for economic agents (Ward 2022).

Our recent research (Madeira et al. forthcoming) shows that the distinction between supply shocks (which move output and inflation in opposite directions) and demand shocks (which move output and inflation in the same direction) is crucial. In particular, it helps to understand disagreement in monetary policy committee deliberations.

The relevance of disagreement in monetary policy committee decisions

Central bank committee decisions are an increasingly ubiquitous feature of monetary policy design (Reis 2013). Committees provide a diversity of views about the best course of action (Blinder 2007). This advantage of committees for decision making over the individual was already noted by Aristotle’s Politics more than 2,000 years ago: “when there are many who contribute to the process of deliberation, each can bring his share of goodness and moral prudence (…), and all together appreciate all”. This diversity of views can be caused by either the members’ diverse preferences (Riboni and Ruge-Murcia 2014) or their private assessments of the economic outlook (Hansen et al. 2014).

Recent research shows that disagreement in monetary policy committees has implications for the economy. Indeed, studies find that dissent negatively impacts stock markets in the US (Madeira and Madeira 2019) and the euro area (Blot et al. 2023). Furthermore, heterogeneity of committee preferences is a predictor of future monetary policy decisions (Riboni and Ruge-Murcia 2014) and changes the effects of fiscal policy (Hack et al. 2023).

Making sense of disagreement in monetary policy

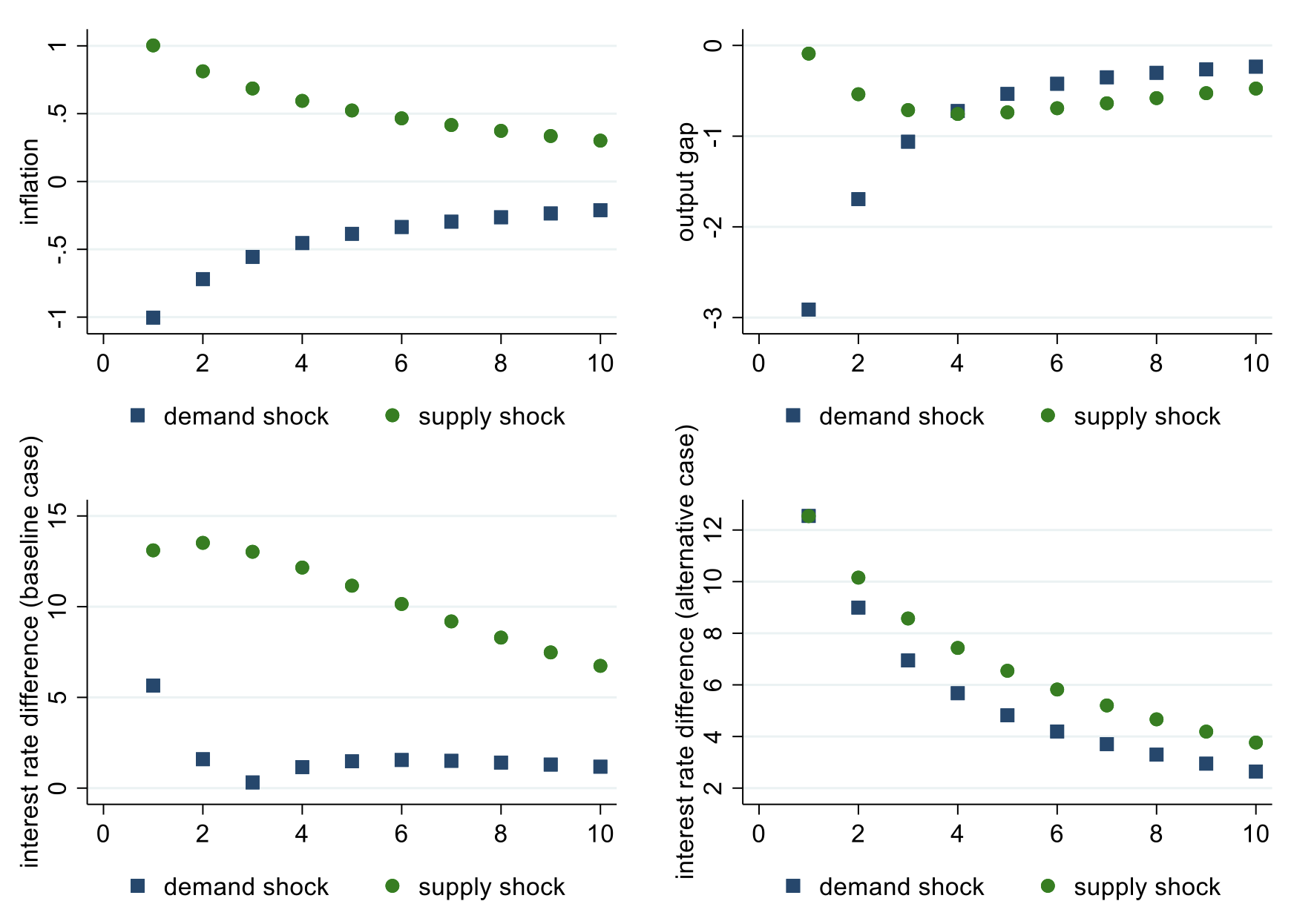

To interpret the causes behind disagreement in monetary policy decisions, we calibrate a simple three-equation New Keynesian (NK) model. The equations are: i) the IS relationship with a demand shock, ii) the Phillips curve with a supply shock, and iii) the Taylor rule with weights on inflation and the output gap. The top panels of Figure 1 show that demand shocks move the output gap and inflation in the same direction, whereas supply shocks move the output gap and inflation in opposite directions. In other words, supply shocks can lead to trade-offs in getting inflation under control versus avoiding a recession. The bottom left panel shows the differences with respect to the preferred interest rate if committee members disagree about the weights of both inflation and the output gap. In this case, we observe that the differences from the preferred interest rate increases much more with supply shocks than with demand shocks. The bottom right panel shows the differences from the preferred interest rate if committee members disagree only with respect to the weight of inflation. In this case, we observe that the difference with respect to the preferred interest rate is similar under supply and demand shocks.

Thus, if committee members have heterogeneous preferences over a dual mandate (for low inflation and full employment), demand shocks should be associated with less disagreement, whereas supply shocks lead to more disagreement.

Figure 1 Effects of supply and demand shocks in a three-equation New Keynesian model

Notes: The upper panels of the figure show the response of inflation (upper-left panel) and output (upper-right panel) to supply and demand shocks. The lower panels of the figure show the path for the gap in the preferred interest rates for hawks and doves in the case of a dual-mandate (bottom-left panel) and a single mandate (bottom-right panel).

How structural shocks drive monetary policy disagreement and uncertainty in market expectations

We show that this simple model describes US monetary policy committee votes since 1957 very well. For this, we use structural shocks obtained from a medium-scale dynamic stochastic general equilibrium (DSGE) model. We also reach similar conclusions when the structural shocks are obtained from a structural vector autoregression (SVAR) model.

We find that supply shocks drive disagreement in US monetary policy meetings. For instance, the 1970s and early 1980s saw frequent dissent votes, which coincided with several supply-related events such as oil shocks. The 1990s and early 2000s were decades with stronger demand shocks. This explains the less frequent dissent during the Greenspan years. Supply shocks increase all types of disagreement, whether in terms of members preferring tighter policies against inflation (‘hawks’), easier policies (‘doves’), or other reasons. Demand shocks are associated with less disagreement. These effects are robust across various specifications, both in the aggregate time series and in the panel data of the individual members’ votes.

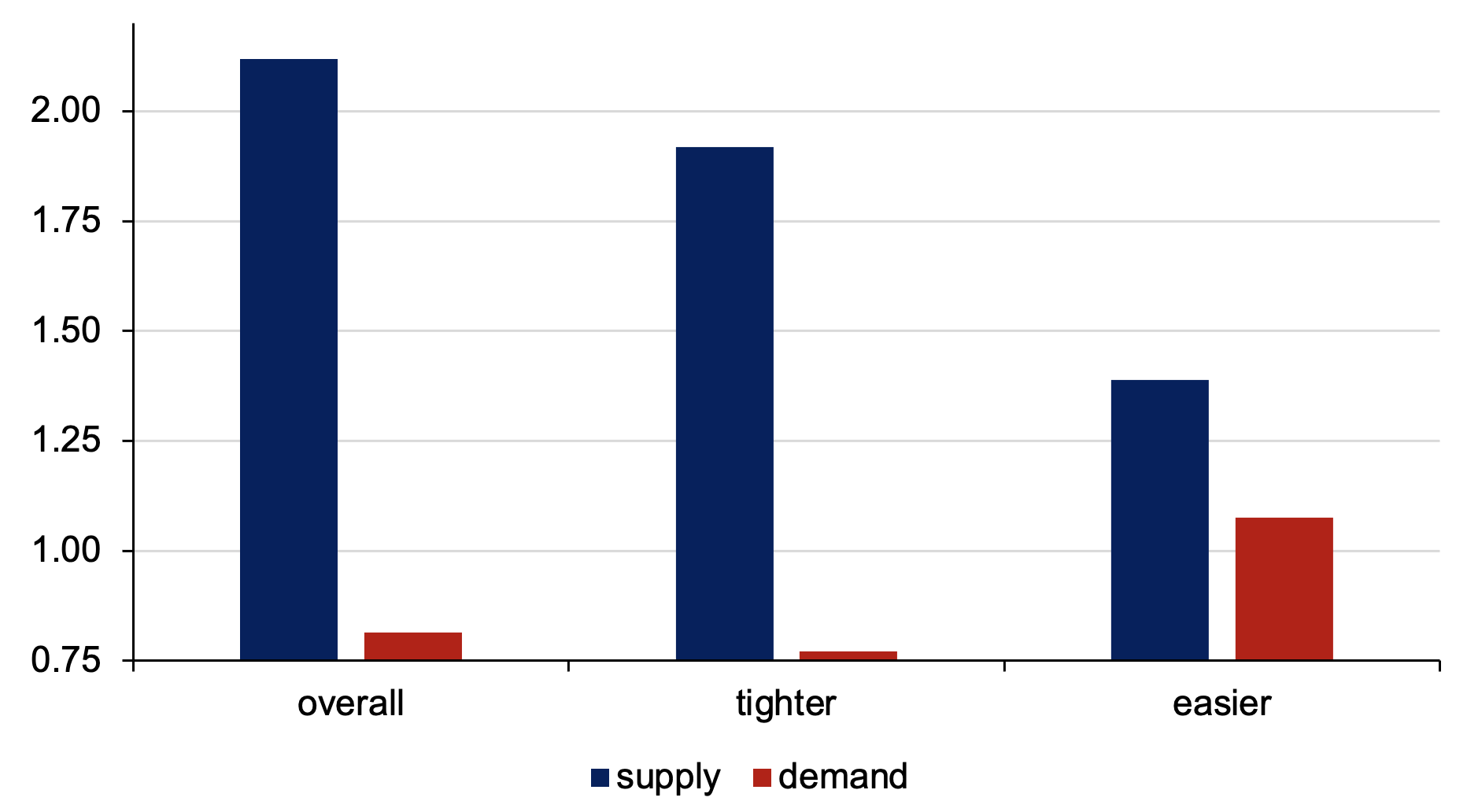

Figure 2 (which summarises logit estimates in Table 4 of the paper) shows that these effects have a large magnitude. The median supply shock increases the probability odds of occurrence of disagreement at a meeting by 212%, with a respective increase of 192% for tighter and 139% for easier policies. Demand shocks lead to lower probabilities of any disagreement and of disagreement for tighter policies, with respective odds ratios of 81% and 77%. Demand shocks have a small (and insignificant) positive effect on dissent for easier policies.

Figure 2 The impact of median supply and demand shock on disagreement odds ratio

Notes: Effect of the median supply and demand shock on the probability of a meeting with disagreement

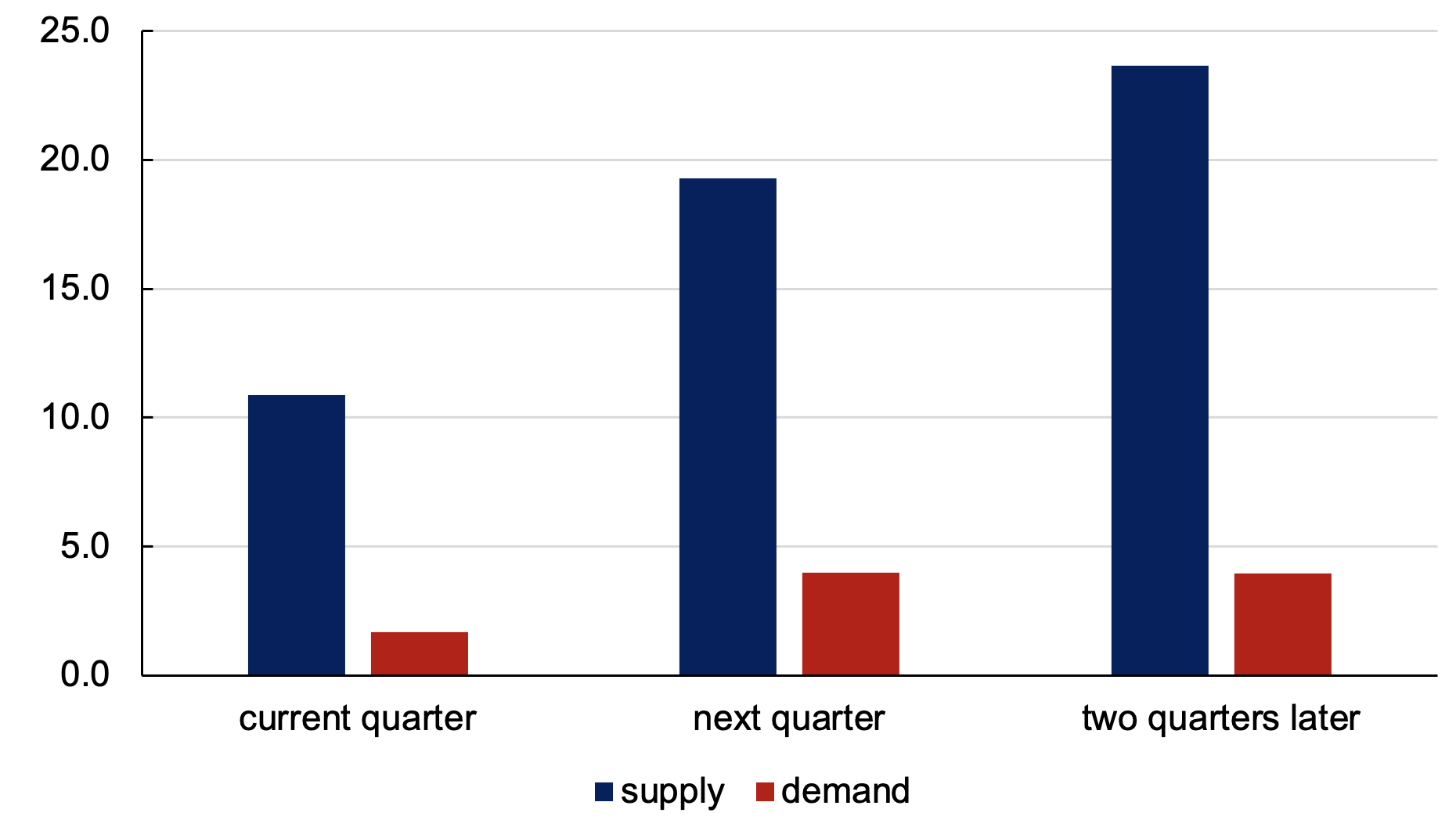

We also find that supply shocks increase interest rate uncertainty among market agents. Our estimates in Figure 3 imply that the median supply shock increases the interquartile range of the three-month Treasury bill interest rates’ forecasts by 11, 19, and 24 basis points, respectively, in the current quarter and the following two quarters. The median demand shock has almost no effect on uncertainty, with an (insignificant) effect lower than four basis points on the future quarters.

Figure 3 Supply shocks increase uncertainty

Note: Effect of the median supply and demand shock on the interquartile range (IQR) forecasts of the three-month Treasury-bill interest rate (basis points)

Disagreement in committees with a single inflation mandate: The case of the Bank of England

The bottom right panel of Figure 1 shows that supply and demand shocks do not affect monetary policy deliberations differently when the central bank has a single mandate (pure inflation targeting). Consistent with this we find that neither supply nor demand shocks explain disagreement at the Bank of England, which has a single mandate for price stability.

Conclusions

Our results show that supply shocks can be a significant cause of disagreement in the conduct of monetary policy when central banks have a dual mandate. These findings are particularly relevant in the present, as the global economy recovers from the Covid-19 pandemic and the impact of the Ukraine war. These events have disrupted global supply chains, labour markets, and commodity markets. Confronted with these shocks, central banks committees may find consensus formation especially challenging, and this in turn may affect the ability of policymakers to steer private sector expectations.

References

Alessandri, P and A Gazzani (2023), “The impact of gas supply shocks in Europe”, VoxEU.org, 25 July.

Aristotle (1948), The Politics, Translated by Barker, Sir Ernest, Clarendon Press.

Baldwin, R (2020), “The supply side matters: Guns versus butter, COVID-style”, VoxEU.org, 22 March.

Blinder, A (2007), “Monetary policy by committee: Why and how?”, European Journal of Political Economy 23(1): 106–123.

Blot, C, P Hubert and F Labondance (2023), “The uncertainty effects of dissent in monetary policy committee”, Mimeo.

Giles, C (2023), “Central banks must keep interest rates high until inflation is tamed, says OECD”, Financial Times, 19 September.

Hack, L, K Istrefi and M Meier (2023), “Identification of systematic monetary policy”, Technical report, Centre for Economic Policy Research.

Jordà, O and F Nechio (2023), “Inflation and wage growth since the pandemic”, VoxEU.org, 9 June.

Hansen, S, M McMahon and C Velasco Rivera (2014), “Preferences or private assessments on a monetary policy committee?”, Journal of Monetary Economics 67(C): 16–32.

Liang, A (2022), “Ukraine war: World Bank boss warns over global recession”, BBC News, 26 May.

Madeira, C and J Madeira (2019), “The effect of FOMC votes on financial markets”, The Review of Economics and Statistics 101(5): 921–932.

Madeira, C, J Madeira and P Santos Monteiro (forthcoming), “The origins of monetary policy disagreement: the role of supply and demand shocks”, The Review of Economics and Statistics, forthcoming.

O’Donnell, N (2022), “Treasury Secretary Janet Yellen on recession fears, inflation and the war in Ukraine”, CBS News, 11 December.

Reis, R (2013), “Central bank design”, Journal of Economic Perspectives 27(4): 17–44.

Riboni, A and F Ruge-Murcia (2014), “Dissent in monetary policy decisions”, Journal of Monetary Economics 66: 137–154.

Seiler, P (2022), “The Ukraine war has raised long-term inflation expectations”, VoxEU.org, 12 March.

Ward, S (2022), “Why the Fed May ‘Yo-Yo’ With Interest Rates”, Morningstar, 12 December.

World Bank (2022), “Risk of Global Recession in 2023 Rises Amid Simultaneous Rate Hikes”, Press Release, 15 September.