Addressing climate change requires individual behaviour change and voter support for pro-climate policies, yet surprisingly little is known about how to achieve these outcomes. Despite the urgency and scale of the challenge, current efforts are underwhelming, in part because sizeable populations around the globe remain sceptical about climate change and policies to tackle it (Bechtel et al. 2022, Dechezleprêtre et al. 2022, Sunstein et al. 2017, Weder di Mauro 2021).

One promising approach to overcoming climate change resistance is the accumulation of human capital through increased educational attainment (Angrist et al. 2021). More-educated individuals may be better equipped to understand the complexities of climate science and have a greater awareness of the risks of climate change. This correlation shows up time and again (Dechezleprêtre et al. 2022). A recent global survey found that people with more education were more likely to see climate change as a major threat (Fagan and Huang 2019).

More education might also yield more transferrable skills across occupations. Thus, more-educated individuals might be prone to vote for policies such as renewable energy subsidies that promote new, less-polluting industries, since they can better adapt skills across new occupations.

Establishing the link between human capital accumulation on pro-climate outcomes

While education and beliefs about climate change are highly correlated, the degree to which education actually causes pro-climate beliefs is challenging to establish. People who choose to pursue more education are, by revealed preference, more forward-looking by investing heavily in their own futures. They are thus also more likely to be concerned with the future consequences of climate change. It might not be education that is causing pro-climate beliefs and actions, but rather that the type of person who is particularly forward-looking both pursues more education and has more pro-climate beliefs. Reverse causality is another challenge. Individuals who believe in climate change might choose to pursue more education to better adapt to a changing world.

We overcome this causal inference challenge by leveraging a new database of government-mandated compulsory schooling laws – an exogenous source of variation in education levels (Angrist et al. 2023). This approach has been used in labour and health economics (Angrist and Krueger 1991, Goldin and Katz 1997, Oreopoulos 2006) yet remains underutilised in studying the link between human capital and climate outcomes.

The data: A new compulsory-schooling law dataset and novel climate outcomes

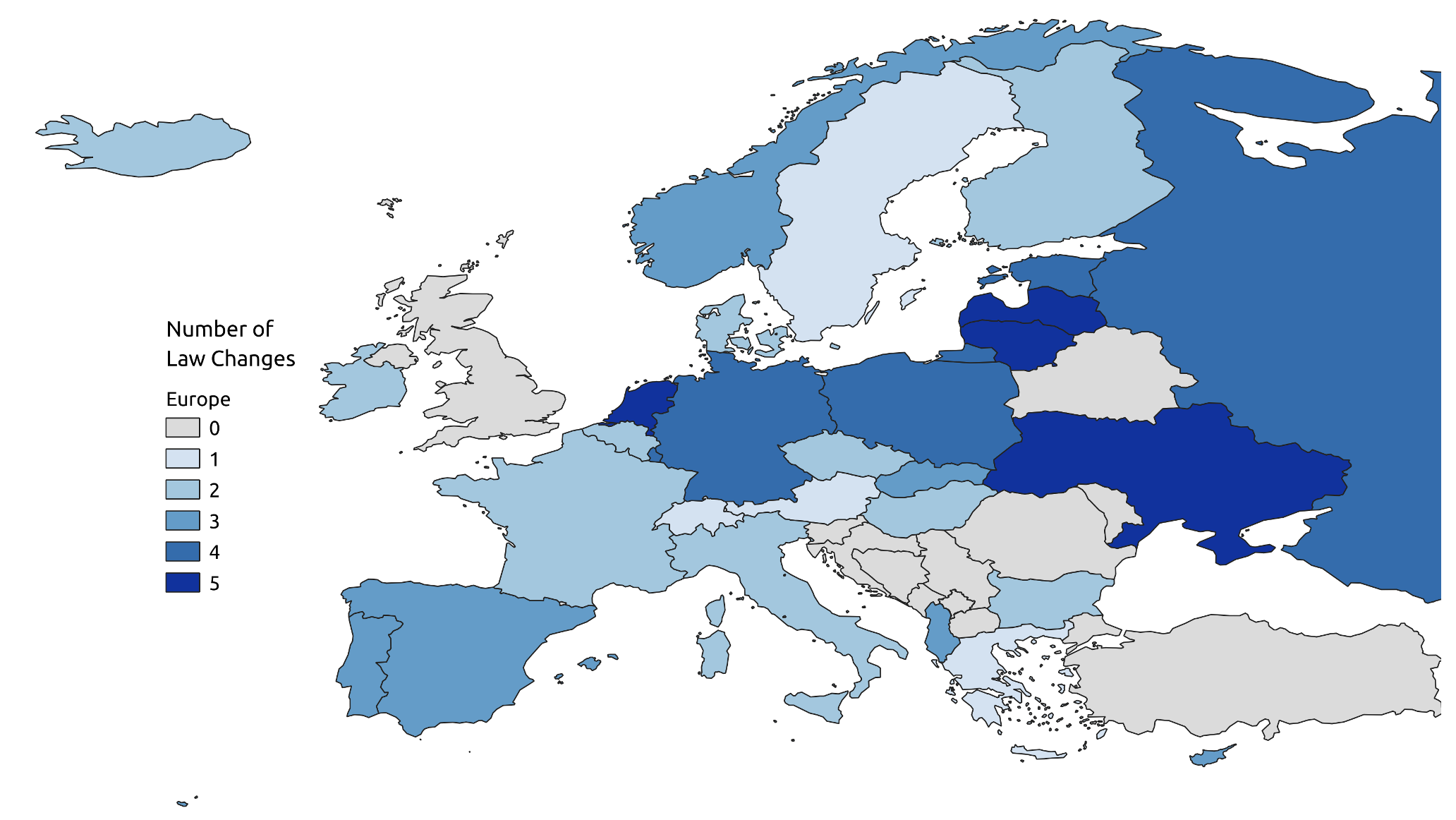

Dozens of countries in Europe enacted education reforms in the 20th century, expanding the number of years of education legally mandated through compulsory-schooling laws. Our paper analyses 53 national reforms of compulsory-schooling laws in 28 countries and identified reforms for which there is a strong first stage – that is, where an increase in years of schooling required by compulsory-schooling laws substantially increases average educational attainment.

Figure 1 Number of changes in national compulsory-schooling laws in European countries

Notes: Education reforms that happened at a regional (subnational) level are not included. These compulsory-schooling laws reforms provide the external variation in educational attainment for Angrist et al. (2023) to assess the causal effects of education on climate beliefs, behaviours, policy preferences, and voting.

Europe also has large, harmonised multi-country surveys, enabling credible within- and across-country analyses on various outcomes, with recent climate modules added to the European Social Survey. The European Social Survey is conducted every two years across dozens of European countries, using stratified random sampling with a total sample size ranging from 20,000 to 40,000 individuals per round. It is a large micro data set capturing information on a host of social issues and is harmonised over time and across countries.

In 2016, the European Social Survey introduced novel questions on climate outcomes, such as ‘How often do you do things to reduce energy use?’ and ‘How likely are you to buy energy-efficient appliances?’ Moreover, the Survey collected data on policy preferences such as ‘To what extent are you in favour or against using public money to subsidise renewable energy such as wind and solar power?’

In addition, we conduct novel analysis on one of the most consequential outcomes of all: ‘green voting’. We compile a new green-voting index using data on voting for green parties since 2002. Europe has a robust green-party movement, which has an explicit environmental agenda. Our study codifies a new dataset of green-party voting outcomes, enabling the identification of pro-climate voting behaviour that extends well beyond standard measures of beliefs and behaviours. Moreover, there’s reason to believe that green policy can also have positive spillovers on other pressing social and political issues (Gollier and Rohner 2023).

Results: Significant effects of education on multiple pro-climate measures

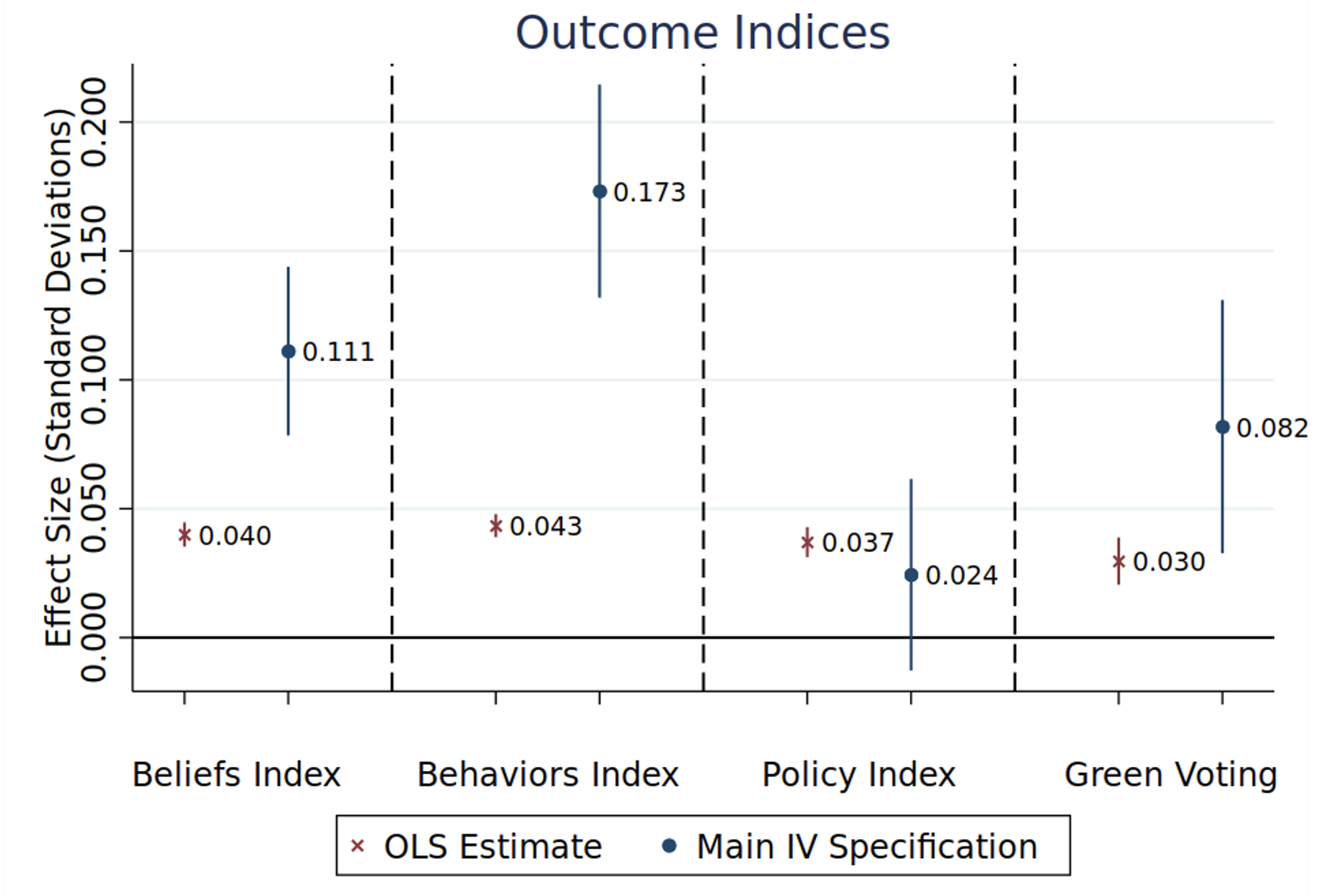

Headline results show that an additional year of education leads to an increase of 3.0 percentage points in pro-climate beliefs, 5.5 percentage points in behaviours, 0.8 percentage points in policy preferences, and 2.3 percentage points in green voting. Relative to status quo rates, these effects are non-trivial, translating into a 4.5% increase for beliefs, 7.8% for behaviours, 1.2% for policy preferences, and a striking 28.2% increase for green-party voting.

These results are notable since education has been conspicuously absent from most major climate change discussions. These findings suggest that expanding general education should be added to the menu of approaches considered in tackling climate change.

Moreover, since low- and middle-income countries prioritise growth, they are often reluctant to switch to less-polluting industries from polluting ones that promote growth, such as those that rely on coal as a source of energy, which can go hand in hand with increasing emissions (Kahn and Lall 2023). In this politically charged context, education might provide a more politically palatable way to offset emissions without the perception of a trade-off in living standards.

Europe is a particularly relevant context, since climate change is receiving substantial attention (Garicano et al. 2022) through efforts such as the European Green New Deal; yet, education remains an underutilised lever. And there remains substantial room to expand education beyond status quo levels. While educational attainment has expanded dramatically in recent decades, the median school-reform law in 2020 in Europe still only guarantees ten years of schooling, a full two years below what is often considered a complete secondary education.

Figure 2 Effect of an additional year of education on pro-climate beliefs, behaviours, policy preferences, and green voting

Notes: Standardised correlations (left, ‘OLS’ estimates) versus causal estimates (right, ‘Main IV’) of the effect of an additional year of education on indices for pro-climate beliefs, behaviours, and policy preferences, as well as voting for a green party with climate policy as a central principle.

Global policy implications

We provide new evidence that investing in education can be a powerful tool to help low-income populations catalyse change in an important set of climate outcomes. Investing in general education appears to be an increasingly high-return investment for multiple reasons, with the list of reasons now also including climate.

Gaps in access to education remain particularly large in developing countries. In sub-Saharan Africa, educational reform laws on average only guarantee eight years of schooling. Further expanding access to education is needed, both in its own right and as a vital part of the battle against climate change.

References

Angrist, J D, and A B Krueger (1991), “Does compulsory school attendance affect schooling and earnings?”, Quarterly Journal of Economics 106(4): 979–1014.

Angrist, N, S Djankov, P K Goldberg, and H A Patrinos (2021), “Measuring human capital using global learning data”, Nature 592: 403–8.

Angrist, N, K Winseck, H A Patrinos, and J S Graff Zivin (2023), “Human capital and climate change”, World Bank.

Bechtel, M M, K F Scheve, and E van Lieshout (2022), “Improving public support for climate action through multilateralism”, Nature Communications 13(1): 6441.

Dechezleprêtre, A, A Fabre, T Kruse, B Planterose, A Sanchez Chico, and S Stantcheva (2022), “Fighting climate change: International attitudes toward climate policies”, NBER Working Paper 30265.

Fagan, M, and C Huang (2019), “A look at how people around the world view climate change”, Pew Research Center, 18 April.

Garicano, L, D Rohner, and B Weder di Mauro (2022), “Increased urgency for the green transition in Europe”, VoxEU.org, 23 September.

Goldin, C, and L Katz (1997), “Why the US led in education: Lessons from secondary school expansion, 1910 to 1940”, NBER Working Paper 6144.

Gollier, C, and D Rohner, eds. (2023), Peace not pollution: How going green can tackle both climate change and toxic politics, CEPR Press.

Kahn, M, and S Lall (2023), “Collapse revisited: Climate change and the development of middle-income countries”, VoxEU.org, 18 January.

Stantcheva, S, A Sanchez Chico, B Planterose, T Kruse, A Fabre, and A Dechezleprêtre (2022), “Fighting climate change: International attitudes toward climate policies”, VoxEU.org, 14 October.

Oreopoulos, P (2006), “Estimating average and local average treatment effects of education when compulsory schooling laws really matter”, American Economic Review 96(1): 152–75.

Sunstein, C R, S Bobadilla-Suarez, S C Lazzaro, and T Sharot (2017), “How people update beliefs about climate change: Good news and bad news”, Cornell Law Review 102.

Weder di Mauro, B (2021), Combatting climate change: A CEPR collection, CEPR Press.