The surge in price inflation seen around the world as economies returned to health following the COVID-19 pandemic has been top of mind for policymakers over the past two years. The elevated prices caught many by surprise, following as it did a period of quiescent and, in many advanced economies, slightly below-target inflation.

Explaining the inflation surge has become an important task for economic research. This task has been complicated by a myriad of apparently special factors, including pandemic-induced supply chain disruptions, and the impact on energy markets of the Russian invasion of Ukraine and ensuing policy reactions. But the role of inflation expectations is undisputedly central to this debate. In the words of the Federal Reserve Board chair, if “the public expects that inflation will remain low and stable over time, then, absent major shocks, it likely will. Unfortunately, the same is true of expectations of high and volatile inflation” (Powell 2022).

A tricky issue for observers of expectations is that people hold a wide variety of views about inflation, and it is not clear whose views carry more weight (Malmandier et al. 2022). Yet with a handful of notable exceptions – such as Reis (2021), Tsiaplias (2020) and more recently Brandao-Montes et al. (2024) – the discussion in academic and policy circles has mostly regarded this heterogeneity as noise and focused instead on the ‘consensus’ expectation.

In this column, which is based on our recent paper (Meeks and Monti 2023), we provide a set of novel statistical facts about inflation beliefs reported in surveys of expectations going back more than 40 years. We link those beliefs to the behaviour of inflation in a new way. The result is a rich and nuanced view of the role of expectations in the inflation process and new insights into more than four decades of inflation history in the US.

Different people, different expectations

Economists use many approaches to measure expectations, but among the longest-running and best studied are those obtained by asking people directly about their beliefs. Unsurprisingly, survey respondents disagree about the outlook for inflation. Perhaps more surprising is just how much they disagree and how much this disagreement changes over time.

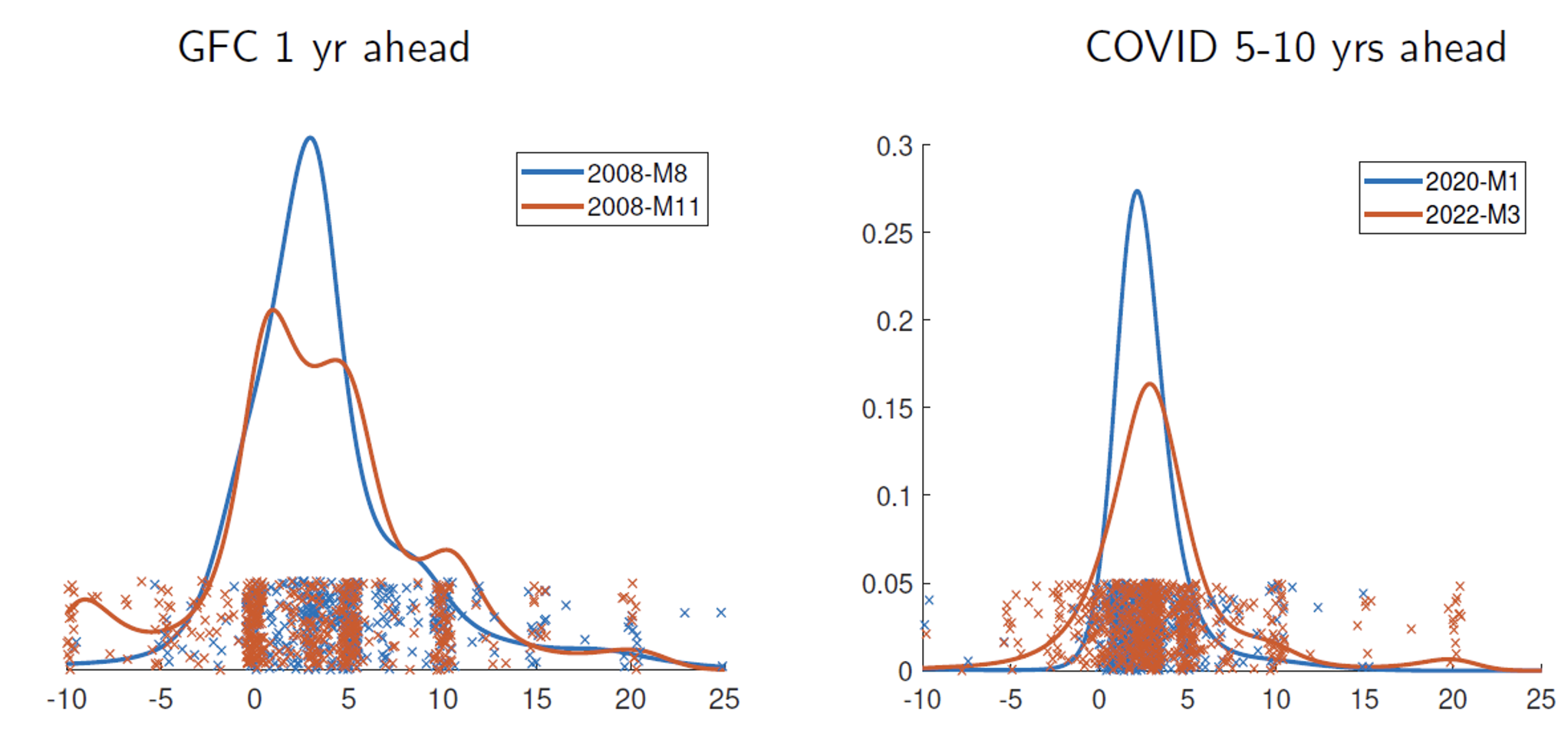

Consider the period of the Great Recession. During 2008 and 2009, the average one year ahead forecast for US inflation reported in the Michigan Surveys of Consumers never fell below 2%. But disagreement changed markedly after the collapse of Lehman Brothers in September 2008, as can be read from the distribution of responses shown in Figure 1 (left panel). Forecasts cluster in as many as three distinct modes; the highest of these was at zero inflation and stayed there for over a year.

Longer-run expectations shift too. Before the COVID-19 pandemic, US households believed that 5–10 year ahead inflation would lie in a fairly narrow range close to the Federal Reserve’s inflation target. But Figure 1 (right panel) shows that by March 2022, before the Fed started its tightening cycle, inflation beliefs had shifted notably, with an appreciable mass of forecasts now outside the 0%–5% range.

Figure 1 Survey respondents’ point forecasts for inflation (1 year ahead and 5 years ahead)

Notes: GFC = Great Financial Crisis. The panels show the distributions of individual survey respondents’ point forecasts for inflation on selected dates. Forecasts are 1 year ahead (left) and 5 years ahead (right). Dates reflect when forecasts were made. The x symbols indicate individual responses (jittered horizontally and vertically).

These patterns are not unique to households. Interpersonal heterogeneity in beliefs has been documented amongst managers of firms and professional forecasters too. The timing and extent of disagreement also appear far from random – it is observed to be greater during periods of macroeconomic disruption and higher uncertainty (the disagreement between individuals, and the uncertainty facing an individual, are different but related concepts).

In our research, we structure and compress the information in a long time series of cross-sectional survey data. We think of inflation forecasts as draws from an underlying smooth distribution function, as illustrated in Figure 1. We estimate those distributions and apply principal component analysis (suitably adapted for functional data) to characterise the most important sources of variation in them (Ramsay and Silverman 2005).

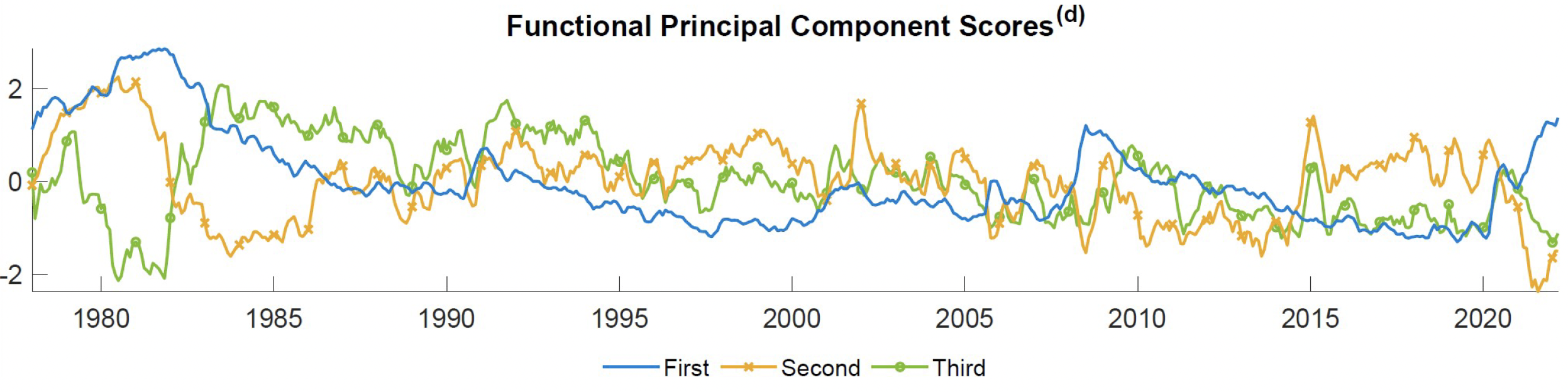

Although distributions of expectations contain rich functional variation, we find that a handful of factors capture most of it (the precise number of factors depends on the type of survey in question). The loadings on the functional factors – the principal component scores presented in Figure 2 – are highly persistent and exhibit periods of co-movement, particularly in the early and late parts of the sample.

Figure 2 First three principal component scores (the ‘loadings’ on the factors)

It is well known that factors themselves can be combined (‘rotated’) in any number of ways, meaning that a precise interpretation is impossible. We find however that much of the observed variation in the factors – and, by extension, the distributions of expectations – can be explained by shifts in the relative prices of frequently-purchased goods. This is in line with detailed microeconometric evidence (D’Acunto et al. 2021) but is based on a far longer time series. So how do these facts relate to inflation itself?

Survey expectations and the Phillips curve

Neglecting heterogeneity in beliefs when modelling inflation can lead to two types of error: errors of measurement, if the average does not adequately summarise the state of expectations relevant for inflation; and errors of theory, if the description of the inflation process that follows from the assumption of uniform beliefs is not appropriately modified.

Our research provides a rigorous econometric method that addresses both of these potential errors. A modified theory of the Phillips curve – one that allows for heterogeneous beliefs – links inflation to both the cross-section average expectations of inflation and to the distribution of beliefs around that average. We provide methods to estimate and test the heterogeneous beliefs Phillips curve, while nesting the standard ‘consensus’ expectation model as a special case (Coibion et al. 2018).

The main finding of our research is a comprehensive rejection of the Phillips curve as conventionally estimated using average expectations alone. Statistical tests confirm that information in the distribution of year-ahead expectations is systematically linked to inflation. Correctly reckoning for distributions is also found to eliminate the effect of lagged inflation, or ‘intrinsic persistence’, a feature of the Phillips curve that is commonly thought to improve its empirical performance but which has only lukewarm theoretical support.

The association between the distribution of expectations and actual inflation is robust to using monthly or quarterly data, considering different sample periods, and including the usual controls for supply factors. Our main results use household survey data, to exploit the long time series available (the advent of firm surveys is too recent for us to use), but they remain when using Survey of Professional Forecasters data and when using UK rather than US data.

COVID-19 inflation

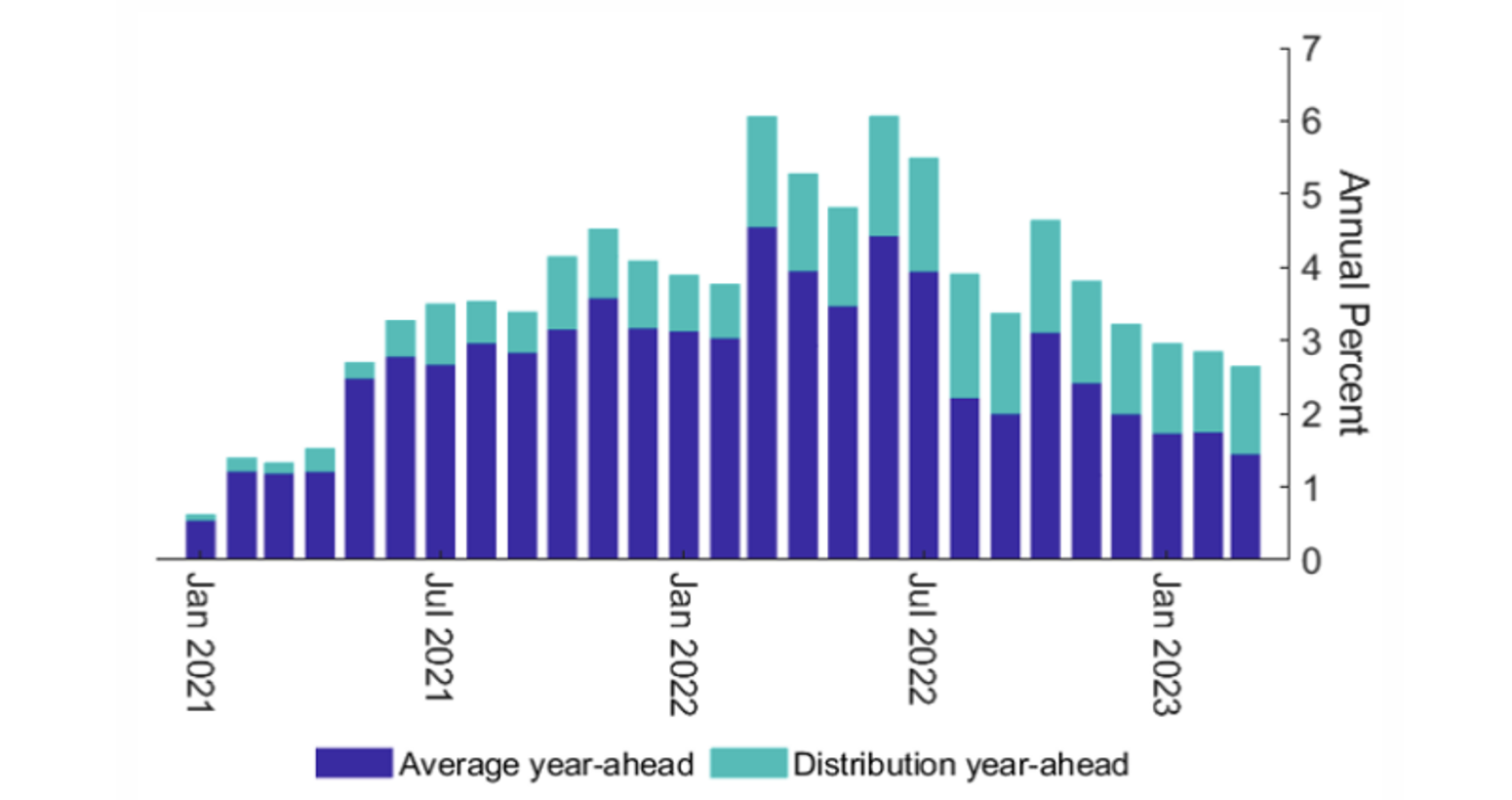

The heterogeneous beliefs Phillips curve may be a useful lens through which to view the role that inflation expectations played during the period of elevated price inflation post-COVID-19. We use it to compute the contributions of household expectations to US inflation since the onset of the COVID-19 pandemic in a model that includes both long- and short-term expectations. We normalise the contributions to be zero in January 2020. Figure 3 illustrates the outcome of this ‘regression accounting’. Together, these components added more than 4 percentage points to inflation by March 2022.

Figure 3 Contributions to fitted month-on-month CPI inflation

Notes: Contributions to fitted month-on-month CPI inflation due to (a) average Michigan survey expectation and (b) the distribution of survey expectation around the average in the heterogeneous beliefs Philips curve. Contribution are normalised to zero in December 2020.

The lighter blue bars show the additional effects of the distribution of year-ahead expectations. The effects are sizeable: these components added a further 2 percentage points to inflation by the same period. The pick-up in longer-term beliefs mattered as well (green bars): the more dispersed and upward-skewed distribution in Figure 1 added another percentage point to inflation. According to the model, the belief that rising inflation would not prove transitory fed through to inflation itself.

Conclusion

There is a robust association between the distribution of household beliefs about future inflation and actual inflation. The usual approach of summarising survey beliefs by a single ‘consensus’ or average forecast is a misspecification which might be particularly problematic at times of macroeconomic disruption. Heterogeneity in expectations is not irrelevant noise: we show that it is important in explaining actual inflation dynamics, and it is found to be predictive of near-term inflation (Brandao-Marques et al. 2024). We hope that further model development will refine our understanding of the complex connection between inflation and distributions of expected inflation.

Authors’ note: The views expressed are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect those of the International Monetary Fund.

References

Brandao-Marques, L G Gelos, D Hofman, J Otten, G K Pasricha, and Z Strauss (2024), “Household expectations help predict inflation”, VoxEU.org, 26 January.

Coibion, O, G Gorodnichenko, and R Kamdar (2018), “The formation of expectations, inflation and the Phillips curve”, Journal of Economic Literature 56(4): 1447–91.

D’Acunto, F, U Malmendier, J Ospina, and M Weber (2021), “Exposure to grocery prices and inflation expectations”, Journal of Political Economy 129(5): 1615–39.

Meeks, R, and F Monti (2023), “Heterogeneous beliefs and the Phillips Curve”, Journal of Monetary Economics 139: 41–54.

Malmandier, U, M Weber, and F D’Acunto (2022), “Learning about inflation expectations from the data”, VoxEU.org, 7 May.

Powell, J H (2022), “Monetary policy and price stability”, speech, 26 August.

Ramsay, J O, and B W Silverman (2005), Functional data analysis, Springer.

Reis, R (2021), “Losing the inflation anchor”, Brookings Papers on Economic Activity (Fall): 307–9.

Tsiaplias, S (2020), “Time-varying consumer disagreement and future inflation”, Journal of Economic Dynamics and Control 116: 103903.