The Great Recession resulted in a strong increase in unemployment across Europe. Between the second quarter of 2008 and mid-2010, the unemployment level in the EU went up by more than 6.7 million, raising the unemployment rate from 6.8% to 9.7% (Eurostat 2017). This has led to an active debate in both academic and policy circles on how to mitigate the welfare effects of unemployment shocks. One view emphasises the role of the family as an insurance device against adverse economic shocks. Alternatively, households can use government programmes and credit markets. However, family networks have advantages over these insurance mechanisms in that they lower monitoring costs and can prevent the familiar problems that plague insurance markets, such as adverse selection and moral hazard (Bentolila and Ichino 2008).

Research on the role of the family as an insurance device against negative income shocks has mostly focused on investigating the responsiveness of women’s labour supply to their husband’s unemployment – the ‘added worker effect’. According to theoretical models of family labour supply, the unemployment of one spouse should increase the labour supply of the other spouse (Ashenfelter 1980). To offset the expected income loss associated with a partner’s job loss, inactive spouses are expected to newly enter the labour market and become ‘added workers’, while already participating spouses are expected to increase the number of hours they work. However, despite these theoretical effects, the existing empirical literature on the added worker effect fails to reach a clear consensus on its magnitude, or even on its existence. Suggested explanations for women’s limited responsiveness to their husband’s unemployment include the presence of other opportunities to smooth family income during times of economic prosperity (Spletzer 1997, Bryan and Longhi 2017), and the crowding-out effect of a country’s unemployment insurance system (Cullen and Gruber 2000, Ortigueira and Siassi 2013). Still, the literature lacks a comprehensive empirical investigation of the circumstances that influence women’s behavioural responses to their husband’s unemployment.

In a recent paper, we aim to unify the previous literature and reconcile the varying results by providing a large-scale investigation of the added worker effect (Bredtmann et al. 2017). In particular, we analyse its variation across welfare regimes and its fluctuation over the business cycle, while also considering a variety of behavioural responses of wives at both the extensive and intensive margins of labour supply. We seek to gain a better understanding of the circumstances that facilitate or hamper spousal labour supply as an insurance device against unemployment shocks.

Overall, we find evidence for the existence of an added worker effect. The increase in wives’ labour supply after the husband’s job loss is largest when unemployment rates are high – that is, when the husband’s job loss is more likely to be permanent and the ability to borrow against income losses is limited. In addition, in high-welfare countries, wives hardly respond to their husband’s unemployment, suggesting that spousal labour supply adjustments are partly crowded out by the generosity of the welfare state.

In our study, we use data from the European Union Statistics on Income and Living Conditions (EU-SILC) covering 28 European countries over the period from 2004 to 2013. The sample covers married and cohabiting couples in which both partners are of working age and neither partner is retired or unable to work. To test the added worker hypothesis, we compare the labour market behaviour of wives whose husband became unemployed during the last 12 months to the labour market behaviour of wives whose husband stayed employed. Wives’ labour market response is measured by five different outcomes:

- whether non-participating wives enter the labour market (by becoming either employed or unemployed);

- whether non-participating wives become employed;

- whether non-participating wives become unemployed;

- whether wives who have not been searching for a job start to search for a job; and

- whether part-time employed wives enter full-time employment.

Our baseline results (for the sample including all European countries) reveal that women whose husbands became unemployed during the last 12 months have a 3.6 percentage point higher probability of entering the labour market than those with a continuously employed husband. This effect, however, is driven only by wives’ changes into unemployment; wives’ probability of becoming employed is not significantly affected by the husband’s employment status. This finding suggests that a husband’s unemployment indeed affects the wife’s willingness to work in the labour market, but also reveals that some wives are limited from the demand side of the labour market in that they are not able to find a job in the short term to offset the loss in household income. Furthermore, there is a strong behavioural response at the intensive margin of women’s labour supply. Women whose husbands became unemployed have a 6 percentage points higher probability of changing from part-time to full-time employment than women with a continuously employed husband.

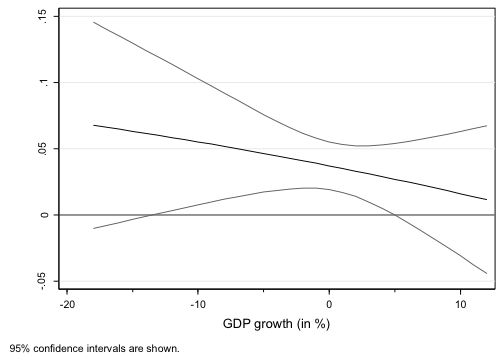

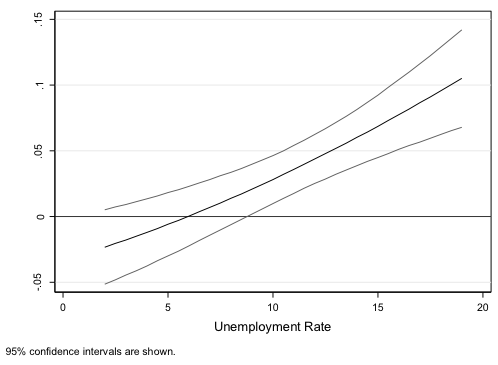

The results further reveal that women’s behavioural response to their husband’s unemployment varies with a country’s economic condition. Whereas women’s probability of entering the labour market decreases only slightly with the country’s GDP growth rate (Figure 1), it strongly increases with the country’s unemployment rate (Figure 2). In general, this result supports the findings of previous literature showing that the added worker effect is stronger during recessions because of the reduced ability to borrow against income losses and the more permanent nature of the husband’s unemployment (Spletzer 1997, Bryan and Longhi 2017). However, it also shows that it is the current situation of the labour market rather than the country’s economic situation in general that matters for labour supply adjustments within the household.

Figure 1 Effect of a husband’s unemployment on his wife’s probability of entering the labour market over the GDP growth rate

Figure 2 Effect of a husband’s unemployment on his wife’s probability of entering the labour market over the unemployment rate

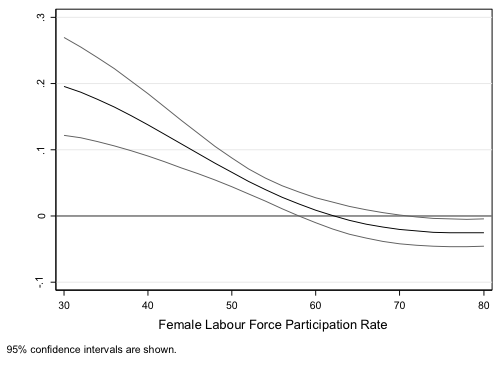

In addition, a wife’s probability of entering the labour market in response to her husband’s unemployment decreases with the country’s female labour force participation rate (Figure 3). As female labour force participation rates have increased remarkably over past decades in most developed countries, this result might provide one explanation why recent studies find hardly any evidence for the existence of an added worker effect in its traditional sense (e.g. Gong 2011). In addition, it points to a natural limitation of the role of family networks as an insurance against labour market uncertainty. If the number of (married) women participating in the labour market continues to increase, families need to rely on alternative insurance mechanisms, such as government programs or precautionary savings.

Figure 3 Effect of a husband’s unemployment on his wife’s probability of entering the labour market over the female labour force participation rate

Lastly, the existence and the magnitude of the added worker effect largely varies across the European countries. Women’s responsiveness to their husband’s unemployment is strongest in countries characterised by less generous welfare states (i.e. the Mediterranean, Central, and Eastern European countries), while it is less present in countries with more generous welfare states (i.e. the Continental European and Nordic countries). In Anglo-Saxon countries, there is even a ‘negative’ added worker effect – in the UK and Ireland, women are significantly less likely to become employed when their husband becomes unemployed. This result might reflect the incentives set by the social security system in these countries. In fact, the UK and Ireland are the only countries within Europe in which the benefits received through both unemployment insurance and unemployment assistance involve some kind of means-testing and the rate of withdrawal of benefit is particularly high. The fact that unemployment benefits are means tested against family income may discourage women from entering the labour market or even encourage working women to leave the labour market when their husband becomes unemployed.

These results support the view that the role of the family as an insurance device against unemployment might be crowded out by the generosity of the welfare state. In particular, they are informative about the optimal design of the unemployment insurance system. Whereas most discussion of the crowding-out effect of unemployment insurance focuses on its effect on the employment of the recipient, our findings suggest that unemployment compensation can create disincentives for the employment of their partners as well. This highlights the importance of an adequate design of the unemployment insurance system in compensating for income losses caused by involuntary job losses, but at the same time maintaining incentives for intra-household labour supply adjustments.

References

Ashenfelter, O (1980) “Unemployment as disequilibrium in a model of aggregate labor supply”, Econometrica 48(3): 547-564.

Bentolila, S and A Ichino (2008), “Unemployment and consumption near and far away from the Mediterranean”, Journal of Population Economics 21(2): 255-280.

Bredtmann, J, S Otten and C Rulff (2017), “Husband’s unemployment and wife’s labor supply – The added worker effect across Europe”, Industrial and Labor Relations Review, forthcoming.

Bryan, M and S Longhi (2017) “Couples’ labour supply responses to job loss: Growth and recession compared”, The Manchester School, forthcoming.

Cullen, J B and J Gruber (2000), “Does unemployment insurance crowd out spousal labor supply?”, Journal of Labor Economics 18(3): 546-572.

Eurostat (2017), “Unemployment statistics”.

Gong, X (2011), “The added worker effect for married women in Australia”, Economic Record 87(278): 414-426.

Ortigueira, S and N Siassi (2013), “How important is intra-household risk sharing for savings and labor supply?”, Journal of Monetary Economics 60(6): 650-666.

Spletzer, J R (1997), “Reexamining the added worker effect”, Economic Inquiry 35(2): 417-427.

Stephens, M (2002). “Worker displacement and the added worker effect”, Journal of Labor Economics 20(3): 504-537.