The discussion on sovereign debt restructuring in the euro area has recently focused on legal considerations, in particular on whether the legal framework should be reformed to make restructurings more ‘viable’, for example via new collective action clauses (Bénassy-Quéré et al. 2018, Tabellini 2018, Pisani-Ferry and Zettelmeyer 2018).

Should sovereign debts in Europe be ‘hard’ or ‘easy’ to restructure? The fundamental trade-off behind this question is well understood, at least theoretically (e.g. Bolton and Jeanne 2007, 2009, Pitchford and Wright 2007, among others). Debt that is easy to restructure is clearly preferable following an adverse shock, since it facilitates a quicker resolution of a debt crisis ex post. However, bonds that are easier to restructure may be perceived as junior and carry higher risk premia, thus raising the ex ante borrowing costs for the governments. In line with this reasoning, Tabellini (2018) argues that a reform to facilitate restructurings in the euro area may increase bond yields, especially in highly indebted countries, and could thus be destabilising.

In a recent paper (Chamon et al. 2018), we provide novel empirical evidence on this question – do bonds that are ‘easy to restructure’ really carry higher yields compared to ‘hard to restructure’ bonds? More generally, do markets care about the degree of legal protection implied in sovereign bond contracts?To answer these questions, we focus on the jurisdiction choice of sovereign debt – a good proxy for de facto (though not de jure) bond seniority.1 Bonds issued under a foreign jurisdiction such as English law or New York law are harder to restructure, because they lie outside the borrower’s legal reach. In contrast, the contract terms of domestic-law bonds can, in principle, be altered retroactively via new legislation (Grund 2017).

Differences between the treatment of local-law and foreign-law bonds featured prominently in the 2012 Greek debt restructuring (Zettelmeyer et al. 2013). On 23 February 2012, the Greek parliament passed the ‘Greek Bondholder Act’, which retroactively introduced collective action clauses with aggregation features into its outstanding domestic-law sovereign bonds.2 After the exchange offer was launched, more than 66% of domestic-law bonds were tendered, thus forcing any minority holders to accept the restructuring offer, even if they voted against it. The foreign-law bonds, in contrast, could not be changed via domestic legislation. The result was a high share of holdouts in those bonds – almost 30% of Greek bonds under English, Swiss, and Japanese law were not restructured and escaped the haircut. These foreign-law bonds (with a face value of more than €6 billion, or about 3% of Greek GDP in 2012) have since been serviced in full and on time.

Our analysis focuses on the euro area sovereign debt crisis, which offers a unique laboratory to disentangle currency, credit, and jurisdiction risk in a clean and straightforward way. To identify the foreign law premium of bonds, we compare bonds by the same sovereign issued under different jurisdictions – for example, an Italian local law bond and one under New York law. Such comparisons are challenging in the case of emerging markets because there is no directly observable risk-free yield curve in the domestic currency (Du and Schreger 2016). But in the case of the euro area we can proxy the domestic currency risk-free yield curve with the German bund yield curve in euros to derive a hypothetical price at which, for example, an Italian 10-year bond issued in US dollars under New York law would have traded if it had been issued in euros instead.3 By adding control variables, we further account for bond liquidity (bid-ask spread) and country-level default risk (CDS spread). We also estimate the implied probability of a selective default, meaning a situation in which domestic-law bonds are restructured while foreign-law bonds are spared.

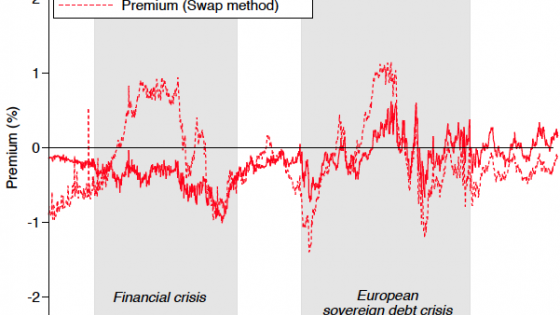

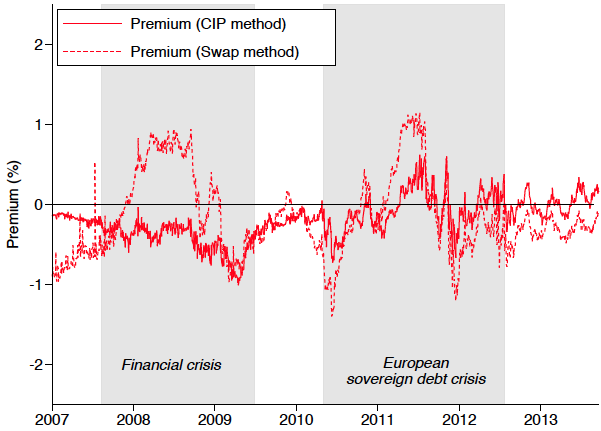

In normal times (with low default risk, as measured by CDS spreads), we do not find a significant foreign-law premium, and little indication that markets price the risk of selective default. The premium can even turn negative during tranquil spells, implying that foreign-law bonds trade at a discount vis-à-vis similar domestic bonds. One explanation for this negative premium is the lower liquidity of the foreign-law bonds, as the market is much smaller than for domestic-law bonds.

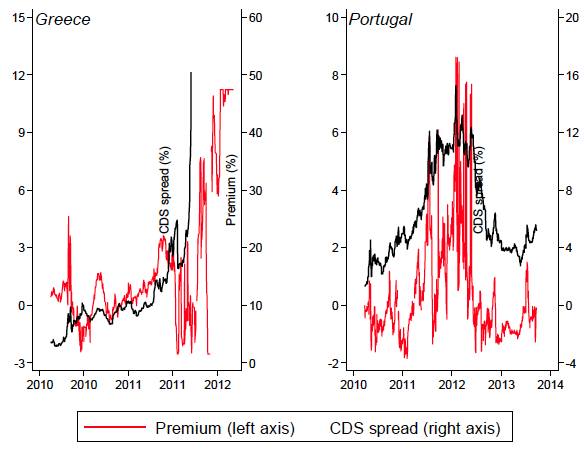

However, during times of high distress (such as in the run up to a debt restructuring) the premium can become very large (see Figure 1). For example, in Greece in early 2012, the yield spread between domestic- and foreign-law bonds exceeded 10 percentage points (see Figure 2). Portugal also experienced a large spike in the foreign-law premium, reaching levels above 5% in 2011 and 2012. Furthermore, the relationship between the foreign-law premium and credit risk appears to be non-linear. Only at high levels of distress does the jurisdiction clause have a notable impact. Even in the cases of Italy and Spain in 2012, the foreign law yield premium rarely reached 1%.

Figure 1 The average foreign law premium in the euro area over time

Note: Some differences between the premium derived via the CIP and swap-based methods are likely due to disorderly conditions in cross-currency swap markets, particularly around the time of the Global Crisis.

Source: Chamon et al. (2018).

Our findings are confirmed for two countries in which we could find perfect ‘twin bonds’, meaning otherwise identical securities that are issued both in domestic and foreign jurisdictions. We identify two such cases of twin bonds from Argentina, and another case where a twin bond can be closely approximated by interpolating two Russian bonds. In both cases, the foreign-law yield premium is negligible during tranquil times, but spikes during the distress episodes in the early 2000s and around the global financial crisis in 2008.

In sum, our evidence suggests that the pricing benefits of issuing ‘hard to restructure’ debt may be lower than often perceived. In normal times, governments do not face higher yields when issuing domestic-law bonds (‘easy to restructure’ debt). On the contrary, these bonds may even trade at premium due to their higher liquidity. Against this backdrop, the concern that contractual reforms will result in higher borrowing costs may be exaggerated (e.g. due to the introduction of single-limb collective action clauses).4 In crisis times, however, countries may indeed be able to reduce their borrowing cost at the margin by issuing in a foreign jurisdiction.5

Figure 2 Foreign law premia and CDS spreads in Greece and Portugal

Source: Chamon et al. (2018).

Authors’ note: This column should not be reported as representing the views of the ECB or the IMF. The views expressed are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect those of the ECB or the IMF, or its policies.

References

Bardozzetti, A and D Dottori (2014), “Collective action clauses: How do they affect sovereign bond yields? ”, Journal of International Economics 92(2): 286–303.

Bénassy-Quéré, A, M K Brunnermeier, H Enderlein, E Farhi, M Fratzscher, C Fuest, P-O Gourinchas, P Martin, J Pisani-Ferry, H Rey, I Schnabel, N Véron, B Weder di Mauro, and J Zettelmeyer (2018), “How to reconcile risk sharing and market discipline in the euro area,” VoxEU.org, 17 January.

Bolton, P and O Jeanne (2007), “Structuring and restructuring sovereign debt: The role of a bankruptcy regime,” Journal of Political Economy 115(6): 901–924.

Bolton, P and O Jeanne (2009), “Structuring and restructuring sovereign debt: The role of seniority,” The Review of Economic Studies 76(3): 879–902.

Carletti, E, P Colla, M Gulati and S Ongena (2017), “The price of law: The case of the eurozone collective action clauses,” Duke University.

Chamon, M, J Schumacher, and C Trebesch (2018), “Foreign-law bonds: Can they reduce sovereign borrowing costs?” Journal of International Economics 114(C): 164–179.

Choi, S J, M Gulati and E A Posner (2011), “Pricing terms in sovereign debt contracts: A Greek case study with implications for the European crisis resolution mechanism,” Capital Markets Law Journal 6(2): 163–187.

Clare, A and N Schmidlin (2014), “The impact of foreign governing law on European government bond yields,” Cass Business School.

Du, W and J Schreger (2016), “Local currency sovereign risk,” The Journal of Finance 71: 1027–1070.

Eichengreen, B and R Portes (1995), Crisis? What Crisis? Orderly Workouts for Sovereign Debtors, CEPR.

Grund, S (2017), “Restructuring government debt under local law: The Greek case and implications for investor protection in Europe,” Capital Markets Law Journal 12(2): 253–273.

Pisani-Ferry, J, and J Zettelmeyer (2018), “Could the 7+7 report’s proposals destabilise the euro? A response to Guido Tabellini,” VoxEU.org, 20 August.

Pitchford, R and M Wright (2012), “Holdouts in sovereign debt restructuring: A theory of negotiation in a weak contractual environment,” The Review of Economic Studies 79(2): 812–837.

Tabellini, G (2018), “Risk sharing and market discipline: Finding the right mix,” VoxEU.org, 16 July.

Zettelmeyer, J, C Trebesch and M Gulati (2013), “The Greek debt restructuring: An autopsy,” Economic Policy 28(75): 513–563.

Endnotes

[1] There is a significant empirical literature analysing the pricing implications of collective action clauses, starting with Eichengreen and Portes (1995), and with more recent contributions by Bardozeetti and Dottori (2014) and Carletti et al. (2018). In contrast, there are only few attempts to quantify the premium on foreign-law bonds compared to domestic-law ones (e.g. Choi et al. 2011, Clare and Schmidlin 2014).

[2] Aggregation features allow voting across the aggregate of outstanding bonds, unlike traditional collective action clauses which require separate votes for each bond series, making it easier for a holdout creditor to buy a blocking stake in a particular series.

[3] We abstract from creditor residency bias and other second-order considerations when pricing that hypothetical price.

[4] Our analysis is based on a starting point where most debt was already issued under domestic law. A large shift from ‘hard’ to ‘easy’ to restructure liabilities may have stronger price implications, especially if it takes place during an episode of heightened market attention to sovereign risk.

[5] Of course, there may be other considerations driving the choice of whether to borrow domestically or abroad, for example, a concern of crowding-out domestic financing.