As demonstrated by three recent progress reports, the ECB is committed to its retail central bank digital currency (CBDC) project (ECB 2022a, 2022b, 2023). Nevertheless, the design choices the reports document raise doubts about the ECB's objectives and strategy. As a consequence, the digital euro might well be dead on arrival, as we explain in Monnet (2023) and Niepelt (2023).

The ECB’s explicit and implicit objectives

The reports state three main objectives for a digital euro. It should:

- preserve European strategic autonomy in the payment sphere,

- help reduce rent extraction by home and overseas payment service providers, and

- serve as a robust monetary anchor when cash transactions decline.

Attaining these objectives requires an attractive payment instrument and widespread adoption across Europe.

In line with G7 and G20 policy principles, the ECB also does no want the digital euro to endanger the central bank’s ability to fulfil its stability mandate, so the digital euro should not add further instability to the financial system. The ECB seems to have jumped to the conclusion that this entails banking as usual. Enter a fourth objective, which the ECB is much less explicit about: do no harm to banks and protect their business model.

This fourth, implicit objective dominates all others. Key design options favoured by the Governing Council trim the digital euro's attractiveness rather than increasing it. They include holding limits for consumers (a few thousand euros), even lower ones for merchants (zero), and negative interest premia during periods of financial stress. Notwithstanding the goal of securing a robust monetary anchor, the ECB appears to view these features as permanent.

Hurdles for digital euro adoption

Regulated financial intermediaries shall be responsible for deploying the digital euro. This raises a serious conflict of interest: a substantial share of banks’ profits originates from offering payment services. Petralia et al. (2019) report that 17% of banks’ total revenue originated from payments in 2017 – a number that most likely increased following the COVID pandemic, which saw an increase in the use of non-cash means of payment. So, banks have no interest in seeing the digital euro alive and well unless digital euro-related bank services such as onboarding or wallet management are even more profitable.

There are more basic hurdles to overcome before the digital euro will widely be adopted. As an ECB (2022c) survey shows, users prefer cash payments for privacy reasons and card payments for the convenience they offer (speeed and security). So, convenience and privacy are key for adoption, but the digital euro will likely be perceived as subpar along both dimensions. The best available private sector solution for retail payments will certainly dominate the digital euro in terms of user convenience. And in terms of privacy vis-à-vis government as well as censorship resistance, many citizens in Europe have limited faith in the ECB. Those who trust in deposit insurance or do not worry about the differences between public and private money will hesitate to swap their payment instruments of choice against the new ECB one. Everybody else might appreciate that the digital euro will maintain its value under any circumstances, but given its likely low yield, they will probably only seek it during flight-to-safety episodes. Other robust sources of demand are not evident either. Business-to-business applications are not the focus of the digital euro project, and merchants with a holding limit of zero will barely be drivers of institutional change and will remain captive to private solutions.

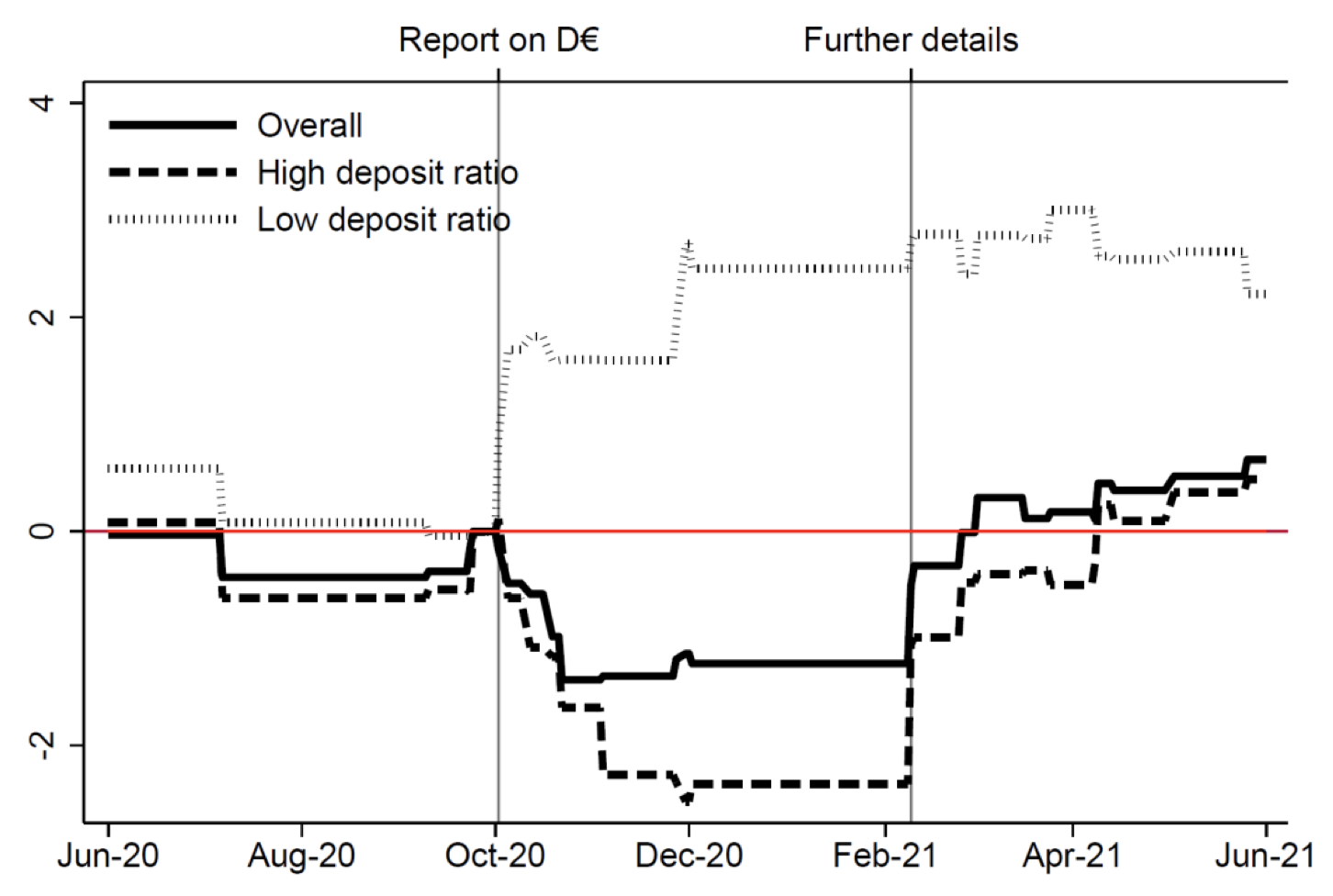

Moreover, markets seem to doubt the digital euro’s potential, too. Burlon et al. (2022) show that after news about the digitial euro in October 2020, share prices of banks that rely more heavily on deposit funding incurred losses relative to those of less deposit dependent competitors, but this difference started to disappear when plans on holding limits and negative premia were made public (see Figure 1 which is reproduced from Burlon et al. 2022). That is, markets appear to view the digital euro in its current form as a side issue for banks, or even an outright failure.

Figure 1 Euro area banks’ stock market reactions to news about central bank digital currency (percentage points)

Notes: the figure reports the results of an estimation model. Each horizontal segment reports the cumulated abnormal returns up to the latest key event, relative to the level on 1 October 2020. The solid line reports the average across all banks in the sample. The dashed and dotted lines report the average with two groups of banks – those with deposit ratios above or below the median, respectively. The two grey vertical lines indicatin the publication of the ECB report on a digital euro on 2 October 2020 and the interview on 9 February 2021.

Private versus social benefits of the digital euro

The previous discussion demonstrates that promoting the digital euro requires an aggressive marketing strategy because private incentives for adoption are limited. However, the pursuit of such an aggressive approach is unlikely as this runs counter to the ECB’s fourth, implicit objective of protecting banks’ existing business model.

This is problematic and could turn the project into a significant missed opportunity, for the potential social benefits of the digital euro substantially exceed its private ones. After all, the case for a digital euro could be quite compelling from a taxpayer and public policy perspective even if it is mixed or even weak from an individual user standpoint. An effective digital euro could not only foster competition in the payment sector but also reduce the social costs of liquidity provision, substantially scale down too-big-to-fail problems and the associated bank regulation, and increase transparency around the costs and benefits of liquidity creation. These potential gains are large and deserve careful scrutiny. Realising them might call for subsidies to foster adoption rather than deterrents and restrictions.

Historians, economists, commentators and (mostly former) high-ranking central bankers alike have highlighted the stability risks of private money creation and fractional reserve banking (e.g. King 2016). The advent of retail CBDC offers the opportunity to rethink the current monetary architecture and to re-evaluate these very features. However, rather than opting for a rethink, the ECB seems to have decided to stick with the status quo. This is tantamount to sacrificing the digital euro on the altar of banking as we know it.

References

ECB (2022a), “Progress on the investigation phase of a digital euro”, September.

ECB (2022b), “Progress on the investigation phase of a digital euro – second report”, December.

ECB (2022c), “Study on the payment attitudes of consumers in the euro area,” December.

ECB (2023), “Progress on the investigation phase of a digital euro – third report,” April.

King, M (2016), The End of Alchemy: Money, Banking, and the Future of the Global Economy, WW Norton & Company.

Monnet, C (2023), “Digital Euro: An assessment of the first two ECB progress reports,” April.

Niepelt, D (2023), “Digital Euro: An assessment of the first two progress reports,” April.

Petralia, K, T Philippon, T Rice and N Véron (2019), Banking Disrupted? Financial Intermediation in an Era of Transformational Technology, Geneva Reports on the World Economy 22, ICMB and CEPR.

Burlon, L, C Montes-Galdón, M A Muñoz and F Smets (2022), “The optimal quantity of CBDC in a bank-based economy,” CEPR Discussion Paper No. 16995.