Even as the need for dedicated macroprudential policy has become widely accepted since the global crisis, fundamental questions on its role within an overall policy framework are still not settled among academics and policymakers. Just how effective is macroprudential policy in achieving the ultimate stability goals of policymakers? Can we rely on macroprudential policy when we want to ‘lean against’ increasing vulnerabilities? Are we better off tightening monetary policy as well, so as to reach into all the cracks (Stein 2013)? Or is it the case, conversely, that macroprudential policy tightening requires monetary policy accommodation at the margin, so as to offset any unwanted dampening of output (Kohn 2015)?

Arguably, a wide range of views on these questions continues to persist, in part because the existing academic literature has not been able to settle them either empirically or at a conceptual level.

Some studies have investigated the benefits and costs of using monetary policy (Svensson 2016) or macroprudential policy (Arregui et al. 2013) to lean against the wind in a binary framework where the economy can fall into a ‘crisis’ state. However, the size of the effects of tightening policy on the probability and depth of the crisis is not easily estimated with precision and remains subject to debate.

A second strand of literature empirically examines the effect of different macroprudential policy tools in slowing the growth of credit or output away from its unconditional mean. While knowledge of these effects is useful, they do not capture the full range of the potential benefits, leaving out the impacts of bolstering the resilience of borrowers and lenders.

A third group of studies examines policy effects using dynamic stochastic general equilibrium (DSGE) models. Although this approach is helpful in understanding specific transmission channels and quantifying their effects, it requires making simplifying assumptions, such as that macroprudential policy acts like a wedge on loan prices, and the overall effects then depend on the specific mechanism featured in the model.

Our research proposes a new empirical approach, which enables us to trace through the effects of both monetary and macroprudential policies on the whole distribution of future output growth and inflation in response to a loosening of financial conditions. This allows policy to have effects across all states of the world—and not just across some binary partition of crisis versus non-crisis states. In addition, it captures net gains through all channels at work in the data, irrespective of whether they arise from slowing buoyant credit, pulling down frothy asset prices, or increasing the resilience of borrowers and lenders to shocks.

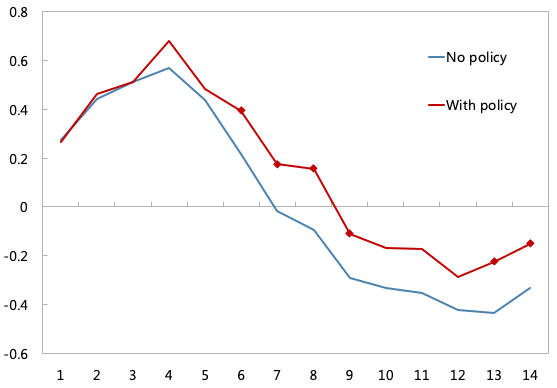

The starting point for this approach is the finding by Adrian et al. (2019) that easing financial conditions have positive effects on output growth in the short term, while they also fatten the tail of bad growth outcomes in the medium term. Conditioning on such easy financial conditions we first ask how policies affect this trade-off, using quantile regressions of output growth on financial conditions, policies, and interactions of policies with financial conditions (Figure 1). We then use these estimates to fit the moments of the full distribution of output growth and inflation over the policy horizon (of 14 quarters), and finally use a standard quadratic loss function to evaluate the effects of policy given the assumed easing of financial conditions.

Figure 1 Marginal effect of FCI shocks on growth-at-risk

Source: Brandao-Marques et al. (2020).

Note: The chart shows the effect of a one standard deviation increase in a financial conditions index (i.e. loosening) on tenth percentile cumulative GDP growth (i.e. Growth-at-Risk) over various quarters. The blue line shows the effect when there is no contemporaneous change in a macroprudential policy index, and the red line shows the same effect when there is a simultaneous one-standard deviation tightening shock in that index.

Throughout we need to be careful to address the potential endogeneity of policy (both monetary and macroprudential) that arises when policy already systemically reacts to real or financial variables. To do so, the main approach we adopt is to compute ‘policy shocks’ as the deviations from estimated policy rules. For monetary policy, therefore, we compute what can be thought of as deviations from a Taylor rule. For macroprudential policy, we similarly estimate deviations from a policy rule that conditions on credit-to-GDP gaps as well as gaps in house price growth.

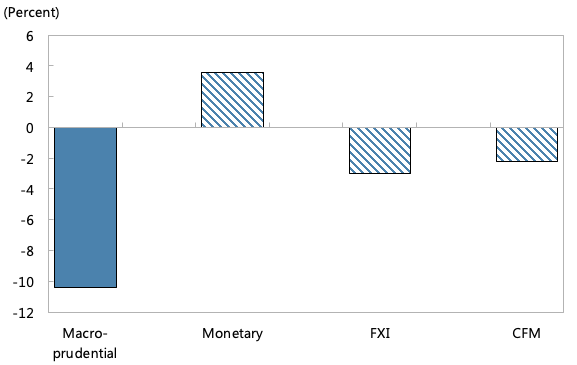

Overall, we find strong support for the notion that macroprudential policy can be effective when used to lean against the wind of easy financial conditions. In the case of quadratic policymaker preferences, we find that macroprudential policy tightening in response to a loosening of domestic financial conditions reduces losses by about 9% (Figure 2), mainly by reducing the future volatility of output.

Digging deeper, we find that tightening ‘borrower-based tools’, i.e. constraints on the permissible loan size relative to the value of assets or on the maximum debt service relative to borrower income, has the strongest effect in containing losses. These findings are in line with those by Alam et al. (2019), who report that the borrower-based measures have larger intended effects on credit but smaller unintended side effects on consumption. The borrower-based tools are useful especially when financial vulnerabilities–-in terms of the outstanding level of credit or the prevailing level of asset prices–-are already elevated. Financial institution-based tools, such as capital or liquidity requirements, on the other hand, are helpful mostly when vulnerabilities are still relatively low.

Figure 2 Effect of policy changes on net losses in response to looser global financial conditions

Source: Brandao-Marques et al. (2020).

Notes: The chart shows the estimated percent reduction of the expected loss, based on a quadratic period loss function (with weights over output ωy = 0.542 and prices ωp=1), and quantile regression results. The exercise shows the results when macroprudential policy, monetary policy, and capital flow measures tighten or when the central bank intervenes in the foreign exchange market by purchasing foreign currency, and global financial conditions are loose. Macroprudential is a shock based on an index of 17 macroprudential measures. Monetary is a shock calculated as the residual of an estimated Taylor rule. FXI is a similar shock based on a measure of FX interventions. CFM is a shock extracted from an index of capital-flow-management measures. See Brandao-Marques et al. (2020) for details. A solid bar denotes statistical significance at the 5% level. Inference is based on a cluster bootstrap.

By contrast, responding to easy financial conditions with a tightening of monetary policy does not impart a net benefit (Brandao-Marques et al. 2020). If anything, a monetary policy tightening increases the loss function that integrates future volatility of output and inflation, in line with warnings in the literature that the damage to output volatility inflicted by such tightening would eclipse the potential benefit of slowing the build-up of financial vulnerabilities (Gourio et al. 2018).

When we turn to the key issue of how to combine macroprudential and monetary policy, our findings quite unequivocally reject the notion that monetary policy should be used alongside macroprudential policy to lean against the wind of easy financial conditions. First, using tighter monetary policy to try and ‘lend a hand’ to a tightening of macroprudential policy turns out to be counterproductive. When macroprudential tightening in the face of easy financial conditions is accompanied with an additional monetary tightening, the increase in loss from the use of monetary policy effectively erases the benefits of the macroprudential tightening. Second, macroprudential policy tightening is instead usefully accompanied by some monetary policy accommodation. This helps offset some of the adverse side effects of macroprudential policy, and thereby further reduces the volatility of output, in line with some of the arguments in the literature (Kohn 2015, Collard et al. 2017).

Our analysis also contains an evaluation of policies in response to changes in global financial conditions, as opposed to domestic ones—an issue of particular importance for small open economies. In that context, we expand our analysis to the use of foreign exchange intervention and capital flow management measures (capital controls). Overall, though, the main message is unchanged: macroprudential policy tightening brings benefits in reducing net losses in response to an easing of financial conditions. Other policies, including foreign exchange interventions and capital controls, do not appear to generate such benefits. The use of monetary policy is particularly tricky, since it can be counterproductive and further increase the net losses stemming from a build-up of financial vulnerabilities.

Authors’ Note: The views expressed herein are those of the authors and should not be attributed to the IMF, its Executive Board, or its management.

References

Adrian, T, N Boyarchenko and D Giannone (2019), “Vulnerable Growth”, American Economic Review 109(4): 1263-89.

Alam, Z, A Alter, J Eiseman, G Gelos, H Kang, M Narita, E Nier and N Wang (2019), “Digging Deeper—Evidence on the Effects of Macroprudential Policies from a New Database”, IMF Working Paper No. 19/66.

Arregui, N, J Beneš, I Krznar, S Mitra and A O Santos (2013), “Evaluating the Net Benefits of Macroprudential Policy: A Cookbook”, IMF Working Paper 13/167.

Brandao-Marques, L, G Gelos, M Narita and E Nier (2020), “Leaning Against the Wind: An Empirical Cost Benefit Analysis for an Integrated Policy Framework”, IMF Working Paper 20/123.

Collard, F, H Dellas, B Diba and O Loisel (2017), “Optimal Monetary and Prudential Policies", American Economic Journal: Macroeconomics 9(1): 40-87.

Gourio, F, A K Kashyap and J W Sim (2018), “The Tradeoffs in Leaning Against the Wind”, IMF Economic Review 66:70-115.

Kohn, D (2015), "Implementing Monetary and Macroprudential Policy: The case of Two Committees", Remarks at the Federal Reserve Board’s Boston Conference on 2 October 2015, Brookings Institution.

Stein, J C (2013), “Overheating in Credit Markets: Origins, Measurement, and Policy Responses”, Speech at the Restoring Household Financial Stability after the Great Recession: Why Household Balance Sheets Matter research symposium sponsored by the Federal Reserve Bank of St. Louis, 17 February.

Svensson, L E.O. (2016), “Cost-Benefit Analysis of Leaning Against the Wind: Are Costs Larger Also with Less Effective Macroprudential Policy?”, VoxEU.org, 12 January.