In response to the Russian invasion of Ukraine beginning in February 2022, the EU, the US, and their allies have imposed wide-ranging economic sanctions. Much of the debates on these sanctions have focused on energy imports from Russia (Bachmann et al. 2022, Bayer et al. 2022, Berger et al. 2022, Gros 2022, Hausmann et al. 2022a). Yet restrictions on exports to Russia are an important part of the sanctions, and the EU, for example, has banned exports to Russia of more than 35% of all six-digit HS products.

Pre-crisis, the EU accounted for 40% of Russia's imports, but less than 2% of EU members' exports went to Russia. This makes it possible for the EU to cut Russia off critical supplies with limited impact on EU's exports. Bans on exports to Russia are thus a potentially effective instrument for sanctions.

But designing such bans is an intricate task. On the one hand, the sanctions need to be coordinated among a broad coalition of countries, which is difficult because sanctions will also affect the imposing countries and for political economy reasons. On the other hand, bans on exports to Russia are intended to serve multiple purposes: They were designed to inflict cost on the Russian economy, but also to undermine its war machinery and its future ability to extract natural resource rents, while limiting the harm to the general population (European Council 2022).

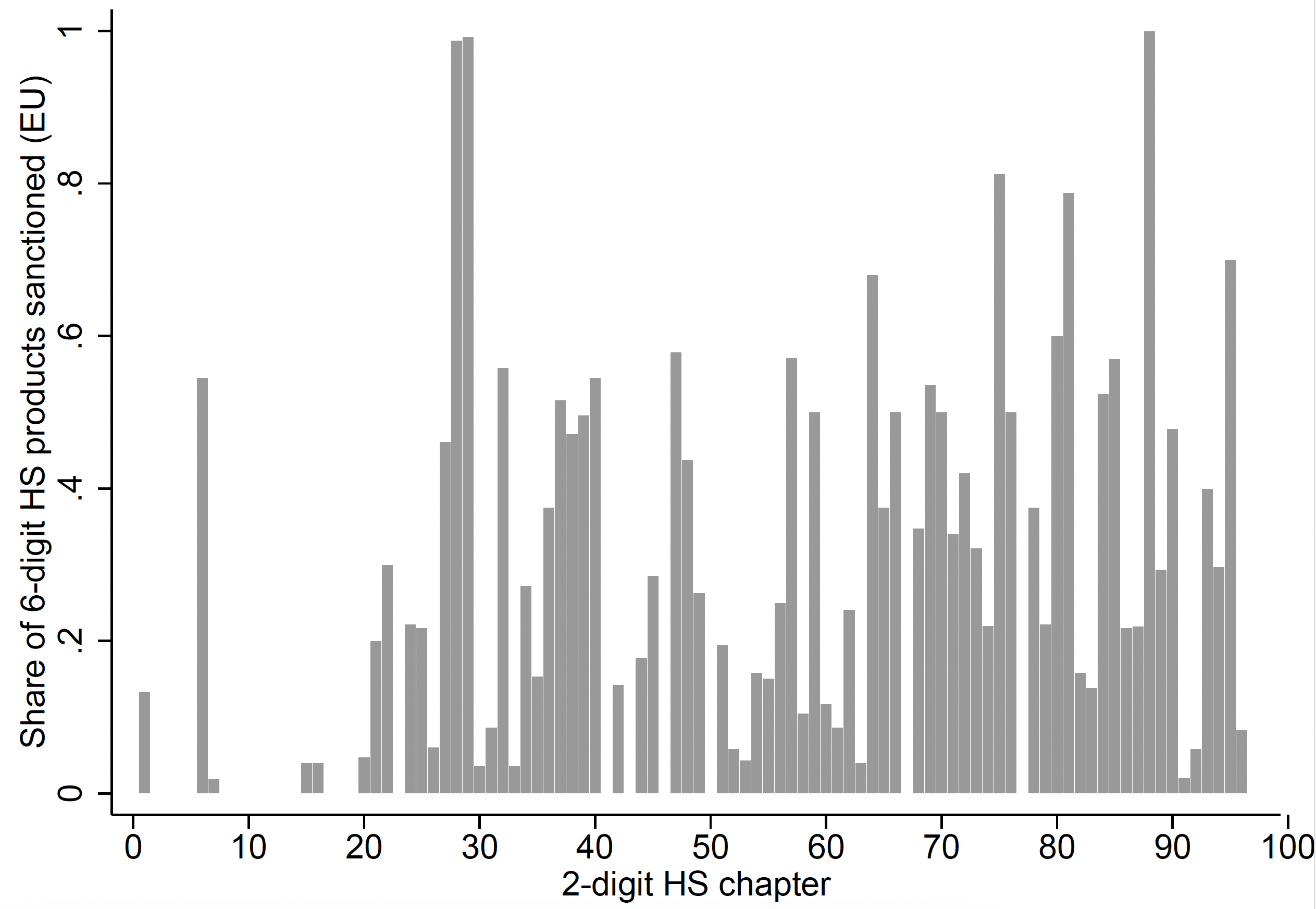

These different motives resulted in sanctions that were imposed at a detailed level of disaggregation as shown in Figure 1, which plots for each two-digit HS chapter the share of six-digit HS-products within that chapter that were subject to an export ban by the EU. Clearly, there is large heterogeneity both within and across two-digit HS chapters in terms of the sanctions, which raises the question how sanctions can be imposed most effectively at such a detailed level of disaggregation.

To shed light on this issue, in Hausmann et al. (2022b) we derive a theoretically grounded criterion that makes it possible to assess ex-ante the economic cost to Russia from a ban on exports of a six-digit HS product by the EU and its allies. While this criterion only reflects part of the motives for the sanctions, it can be readily taken to data and integrated into a more comprehensive analytical process to inform economic sanctions against Russia and in future crisis settings.

Figure 1 Share of six-digit HS products within two-digit HS chapters with an EU ban on exports to Russia

Notes: This figure shows for each two-digit HS chapter the share of six-digit HS products in that chapter that were subject to an export ban to Russia by the EU as of 14 Oct 2022.

Source: Own illustration based on data from https://www.globaltradealert.org/.

A theoretically grounded criterion for prioritising bans on exports based on inflicted economic costs

To analyse export bans, we consider a gravity model where countries trade approximately 5,000 six-digit HS products that are then supplied to domestic downstream producers. We then build on Baqaee and Farhi (2019, 2021) to characterise analytically the economic cost to a sanctioned country from a ban on exports to that country of a six-digit HS product. We derive an approximation for these costs that accounts for non-linear (second-order) effects, which are important as we consider shocks that are large at the product level.

Three key insights emerge from our theoretical analysis regarding the economic cost to the sanctioned country: First, these costs scale with the total expenditure of the sanctioned country on the banned product, i.e. quite intuitively, a ban on exports has ceteris paribus a larger impact if it affects sizeable trade flows. This has been known at least since Hulten (1978), and it is also reflected in our second-order approximation.

Second, ceteris paribus, a ban on exports to a country has a larger effect if it is more difficult for the sanctioned country to substitute the missing imports. In turn, this suggests that a ban is particularly effective for intermediate goods with a low trade elasticity.

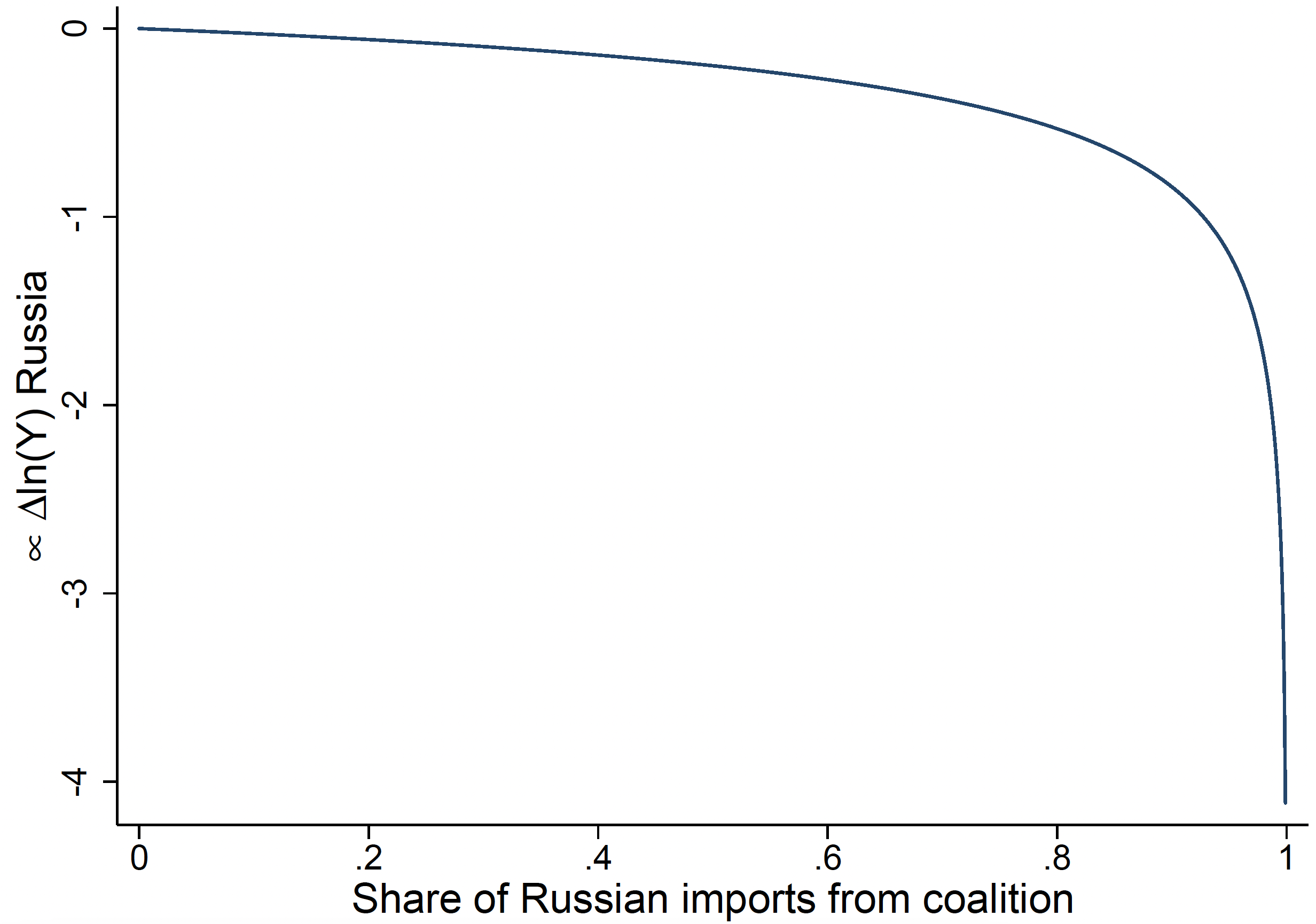

Third, there are large gains from coordinating sanctions among a broad coalition of countries and from sanctioning products with a dominant market position of the coalition. This is illustrated in Figure 2.

Figure 2 Market share of coalition and economic cost to sanctioned country

Notes: This figure illustrates how the economic cost to a sanctioned country (Russia) from a ban on exports by a coalition of countries depend on the pre-shock market share of the coalition. The figure assumes a trade elasticity of 4 and that Russian downstream buyers of the sanctioned product have an elasticity of substitution across their inputs of 0.2. Further details are provided in Hausmann et al. (2022b).

Our results can be readily taken to the data to inform policy. We show this for the case of bans on exports to Russia and compare a ranking of products based on our criterion to sanctions in place by the EU and the US. This comparison reveals that the sanctions are not systematically related to our arguments once we condition on Russia’s total imports of a product from coalition countries. Hence, our arguments suggest scope for increasing the economic costs to Russia from these sanctions.

To explore this potential more systematically, we perform a quantitative analysis based on a trade model with international input-output linkages. We calibrate this model to match pre-crisis trade flows in the World Input-Output Database. We then feed into the model industry-level trade cost shocks from a coalition of countries to Russia (see the notes to Figure 3 for details on the coalition). These shocks are calibrated to mimic bans on exports of underlying six-digit HS products.

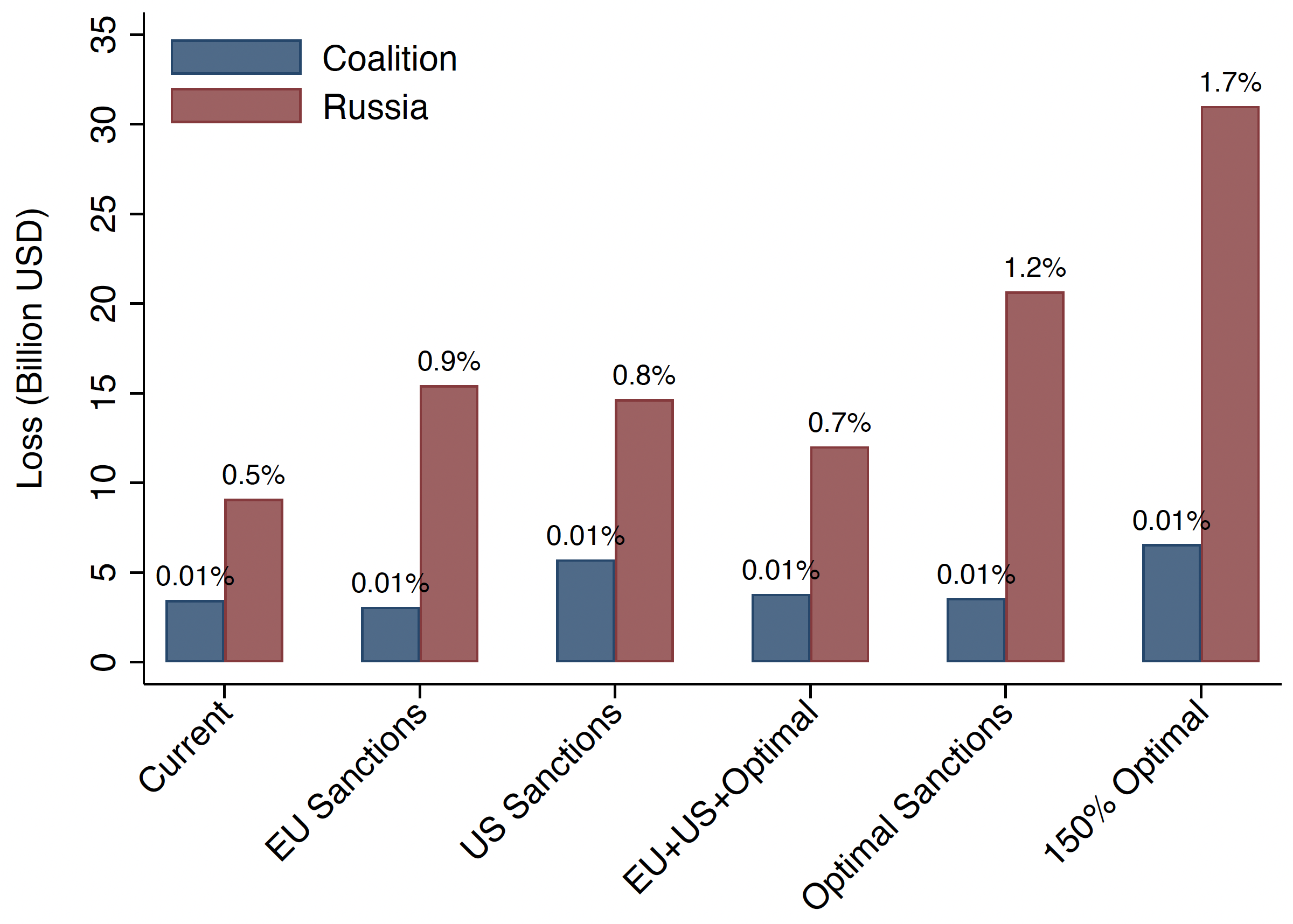

Figure 3 summarises our quantitative results. The figure shows the economic losses in absolute terms (height) and relative to GDP (percentage on top of bars) for Russia (right red bar) and the sanctioning coalition (left blue bar), respectively, for six different sanctions regimes. All scenarios suggest that bans on exports are very effective, with the associated losses relative to GDP around 100 times larger for Russia than for coalition countries.

The quantification further suggests large gains from improved coordination of the sanctions and from re-designing them based on our arguments. This may be seen from comparing scenarios 2 (‘EU Sanctions’), 4 (‘EU+US+Optimal’), and 5 (‘Optimal Sanctions’). In all three scenarios, the total sum of coalition exports to Russia that are banned is the same, namely that of scenario 2 where we assume that all coalition countries adopt EU sanctions.

According to our quantification, this perfect coordination increases the costs to Russia by about 25% when compared to the status quo of EU and US sanctions (scenario 2 versus scenario 4).

When further focusing sanctions on the products with highest impact according to our arguments, the costs to Russia increase by an additional 30% (scenario 5 versus scenario 2) with little to no effect on the cost to coalition countries.

Figure 3 Economic losses for Russia and the coalition for six different sanctions scenarios

Notes: This figure shows the economic losses in absolute terms (height) and relative to GDP (percentage on top of bars) for Russia (right red bar) and the sanctioning coalition (left blue bar), respectively, for six different sanctions regimes. The coalition is the EU, the US, the other G-7 member states, Australia, South Korea, and Taiwan. For further details please refer to Hausmann et al. (2022b).

Concluding remarks

We develop a theoretically grounded, transparent, and easily implementable criterion that makes it possible to prioritise export restrictions based on their economic impact on a targeted country. This is an important motive for sanctions, and we believe that our analysis can thus provide valuable inputs for the design of effective sanctions.

Yet our analysis ignores factors of the economic costs to Russia such as the possibility of parallel imports, interaction effects between the sanctions, or potential bottlenecks in value chains that can have large cascading effects. Moreover, when designing policy, other motives have to be taken into account as well such as ethical considerations or the desire to cut Russia off critical inputs for its military, for example.

Our analysis is thus best understood not as a blueprint for policy, but as an easily implementable input into a more comprehensive analytical process.

References

Bachmann, R, D Baqaee, C Bayer, M Kuhn, A Löschel, B Moll, A Peichl, K Pittel and M Schularick (2022), “What if? The economic effects for Germany of a stop of energy imports from Russia”, Policy Brief 28, ECONtribute.

Baqaee, D and E Farhi (2019), “The macroeconomic impact of microeconomic shocks: Beyond Hulten’s theorem”, Econometrica 87(4): 1155–1203.

Baqaee, D and E Farhi (2021), “Networks, barriers, and trade”, NBER Working Paper 26108.

Bayer, C, A Kriwoluzky and F Seyrich (2022), “Stopp russischer Energieeinfuhren würde deutsche Wirtschaft spürbar treffen, Fiskalpolitik wäre in der Verantwortung”, DIW aktuell 80, Deutsches Institut für Wirtschaftsforschung (DIW) Berlin.

Berger, E M, S Bialek, N Garnadt, V Grimm, L Other, L Salzmann, M Schnitzer, A Truger and V Wieland (2022), “A potential sudden stop of energy imports from Russia: Effects on energy security and economic output in Germany and the EU”, IMFS Working Paper 01/2022.

Borin, A, G Cappadona, F P Conteduca, B Hilgenstock, O Itskhoki, M Mancini, M Mironov and E Ribakova (2023), “The impact of EU sanctions on Russian imports”, VoxEU.org, 29 May.

Chowdhry, S, J Hinz, K Kamin and J Wanner (2022), “Sanctions coalitions: Stronger together”, VoxEU.org, 30 October.

European Council and Council of the EU (2022), “EU sanctions against Russia explained”, accessed on 11 January 2023.

Gros, D (2022), “Optimal tariff versus optimal sanction: The case of European gas imports from Russia”, Technical report, CEPS.

Hausmann, R, A Loskot-Strachota, A Ockenfels, U Schetter, S Tagliapietra, G Wolff and G Zachmann (2022a), “Cutting Putin’s energy rent: Smart sanctioning Russian oil and gas”, Faculty Working Paper 412, CID at Harvard University.

Hausmann, R, U Schetter and M Yildirim (2022b), “On the design of effective sanctions: The case of bans on exports to Russia”, Faculty Working Paper 417, CID at Harvard University.

Hulten, C R (1978), “Growth accounting with intermediate inputs”, The Review of Economic Studies 45(3): 511–518.